Hendrick Hondius the Elder’s Pictorum aliquot celebrium, præcipué Germaniæ Inferioris, effiges (The Hague, 1610), which contains 68 portrait prints of Netherlandish artists.

You can browse pages below, view a list of the 1610 Hondius pages, or use our turn the page feature to explore the book.

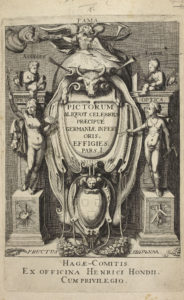

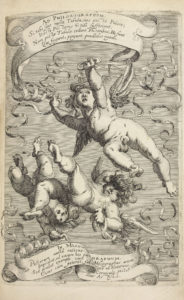

Titlepage To Part 1

Titlepage To Part 1

Etching

22.7 x 14.8 cm

Attributed to Simon Frisius

Transcription and translation of texts:

Over figure with trumpet in upper margin:

FAMA: Fame

On map below Fame:

EUROPA: Europe

Over putto sketching on left:

ASSIDUUS: Diligent

Over putto sketching on right:

LABOR: Labour

Over female figure on left with caduceus and palette:

PICTURA: Painting

Over female figure on right with compass and set squares:

OPTICA: Optics

Beneath pedestals, on either side of garlands of flowers and fruits:

FRUCTUS LABORUM: Fruits1 of Labours

Publisher’s address in bottom margin:

HAGÆ-COMITIS/EX OFFICINA HENRICI HONDII./CUM PRIVILEGIO:

The Hague, from the press of Henricus Hondius, with the privilege.

In central cartouche:

PICTORUM/ ALIQUOT CELEBRIUM/ PRÆCIPUÉ GERMANIÆ INFERI/ORIS,/ EFFIGIES. PARS. 1.:

Effigies of some famous painters, especially of Lower Germany. Part 1

Hollstein 20082 no.155

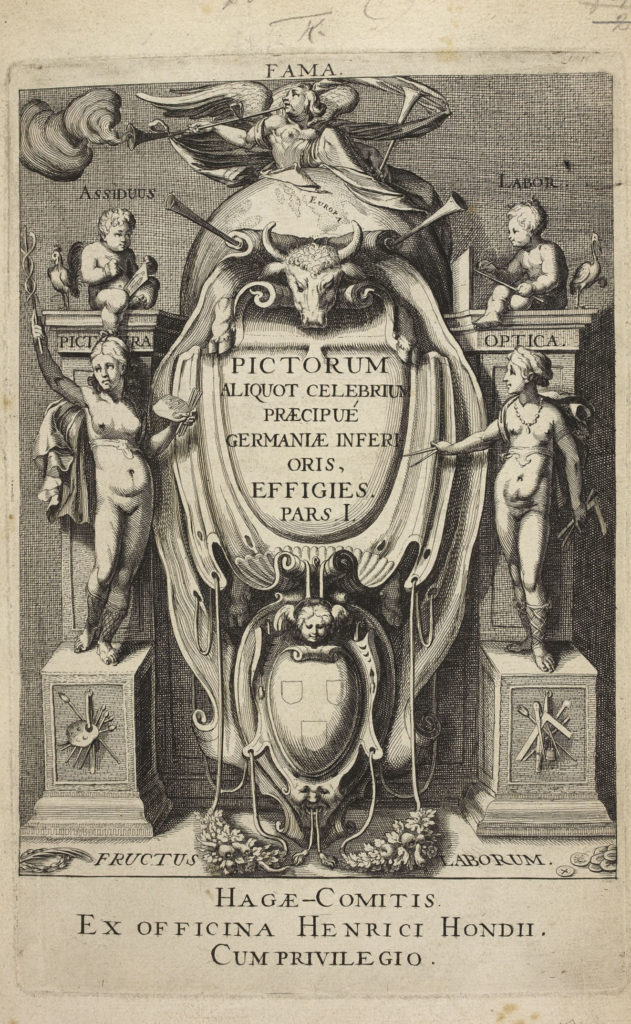

Poem to the Lovers and Admirers of Pictures

Poem to the Lovers and Admirers of Pictures

Etching and engraving

19.5 x 12.2 cm

Transcription:

PICTURÆ AMATORIBUS, ADMIRATORIBUSQ.

Cúm Tabulas multúm miramur imagine pictas

Exhibuit variâ quas bene docta manus :

Mirificé omnigeno & laeto quae ducta colore

Cúm pascunt multúm mentem, animum atque oculos;

PICTORES ipsos etiam spectasse voluptas,

Qui fingunt, pingunt non sine judicio.

Pictores sunt hîc varii : labor omnibus idem

Non est, delectat quod variúmque novum.

Omnibus haud idem genius. placet ille Colore,

Vmbris : hic gratis floribus, Arboribus.

Agros scité alter Pingit, tumida Aequora, Rupes :

Vrbibus ast alter clarus, Imaginibus.

Omnes ferme Hi sunt peperit quos Belgica, mater

Artificum : ingenio cedere turpe putat.

Hos inter quosdam celebravit maximus olim

Pictorum Censor carmine Lampsonius.

Quosdam etiam immistos Belgis spectare licebit.

Forté alios plures nostra datura manus.

Felix ô seclum, quo rursus vivit Apelles,

Quo Zeuxis, Phidias vivit et ipse Myron.

HENR. HONDIVS

Translation:

TO THE LOVERS AND ADMIRERS OF PICTURES

Since we greatly admire pictures painted with varied images, which [pictures] the well-taught hand presents, and which, wonderfully drawn with every sort of joyful colour, greatly nourish the mind, the spirit and the eyes, it is also a pleasure to look at the PAINTERS themselves, who make and paint, not without discernment. Here are various painters: not all have the same task, because what is new and varied pleases.3 All do not have the same genius. One gives pleasure with colour [and] shades; another with pleasant flowers [and] trees. [Yet] another skilfully paints fields, the swelling sea [and] rocks, [while] another is famous for cities [and] images.4 Almost all these are those5 that Belgium, mother of artists, brought forth: she thought it disgraceful to yield6 [to other nations] in genius. Among these, Lampsonius, the greatest censor of painters,7 once celebrated some in verse. You will also be able to see certain men mixed in with the Belgians. Perhaps our hand will produce some more. O happy age, in which Apelles lives again, in which Zeuxis, Phidias and Myron himself live.

HENDRICK HONDIUS

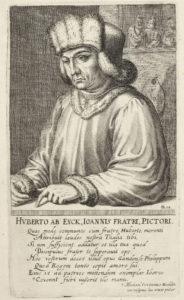

To the lover of things written and drawn

To the lover of things written and drawn

Etching and engraving

19.5 x 12.2 cm

Transcription of text in banderole above flying putto:

AD PHILOZOGRAPHUM.

Si tibi sint nullae Tabulae, nec picta Poësis ;

Docti Pictores hi tibi sufficiant.

Nam pictae Tabulae cedunt Pictoribus. Hi sunt

Qui fingunt, pingunt quodlibet ingenio.

Translation of text in banderole above flying putto:

To the lover of things written and drawn.1

If you own no paintings, nor illustrated poems2, let these learned painters be enough for you. For painted pictures yield to painters. They are the ones who form and paint whatever they please with their genius.

Transcription of text in banderole below the falling putti:

IN MISOGRAPHUM.

Pictorum nullâ ratione Miscographus artem

Improbat, ad vivum hos pingere nil blaterans

Sed probat exemplo vivo Cornicula, pictas

Uvas cum peteret, fallitur Artifice.

Translation of text in banderole below the falling putti:

Against the hater of things written and drawn.3

The hater of painting attacks without reason the art of painters, babbling that they paint nothing lifelike.4 But the little crow proves [the opposite] by a living example: when it tried to get the painted grapes, it was deceived by the artist.

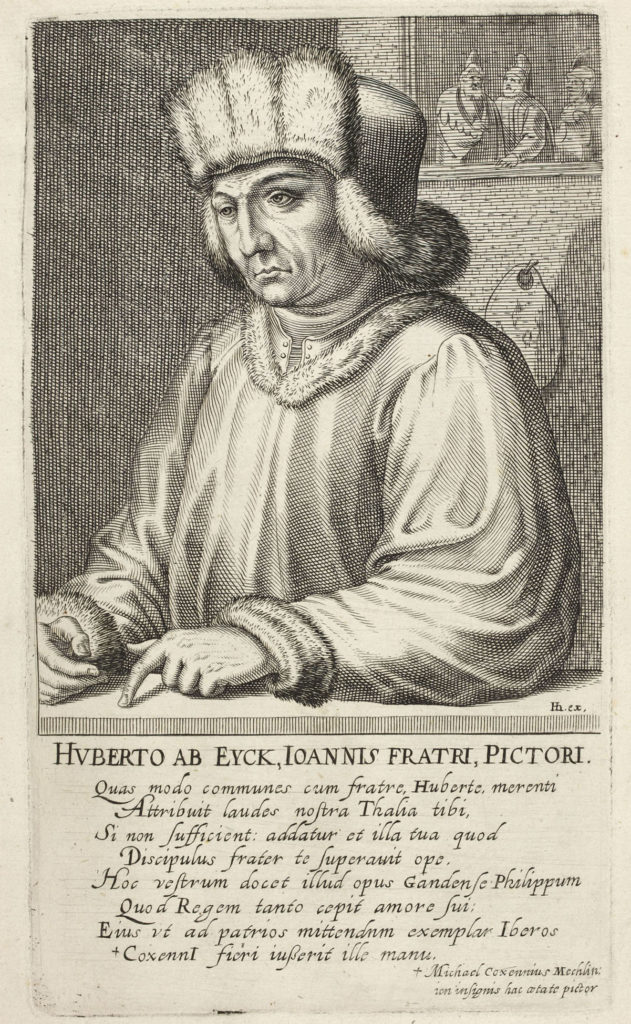

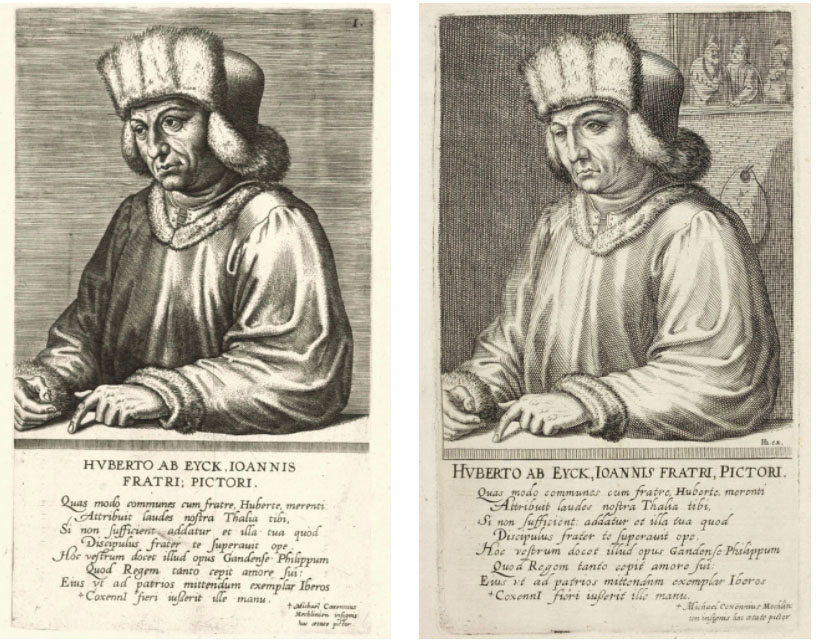

9. Hubert Van Eyck

9. Hubert Van Eyck

Engraving

Signed 'Hh ex.' by Hendrick Hondius

Copy in same direction as Cock 1572 engraved Pictorum

20.7 x 12.0 cm

Transcription of Inscription [Lampsonius]:

HUBERTO AB EYCK, IOANNIS FRATRI, PICTORI.

Quas modo communes cum fratre, Huberte, merenti

Attribuit laudes nostra Thalia tibi,

Si non sufficient : addatur et illa tua quod

Discipulus frater te superavit ope.

Hoc vestrum docet illud opus Gandense Philippum

Quod Regem tanto cepit amore sui :

Eius ut ad patrios mittendum exemplar Iberos

+Coxennii fieri iusserit ille manu.

+Michael Coxennius Mechlin:

in insignis hac aetate pictor

Translation of Inscription [Lampsonius]:

To Hubert van Eyck, brother of Jan, painter.

Hubert, if the praises which our Thalia8 recently attributed to you along with your deserving brother are not enough, let this [praise] of yours be added, that your brother, as your student, outdid you in ability9 That work of yours in Ghent10 teaches this, which filled Philip with such love of it,11 that he ordered a copy of it to be made by the hand of Coxennius, to be sent to his native Spaniards.

Note (referring to Coxennius) – Michael Coxennius of Mechelen, a famous painter of that age.

Hollstein 1994 no. 82

Karel Van Mander's biography of Hubert van Eyck

Grove Art Online biography

View the 1572 print

View the 1572 print

View both prints side by side

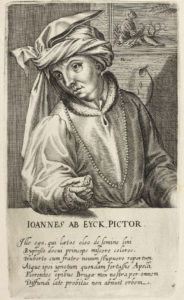

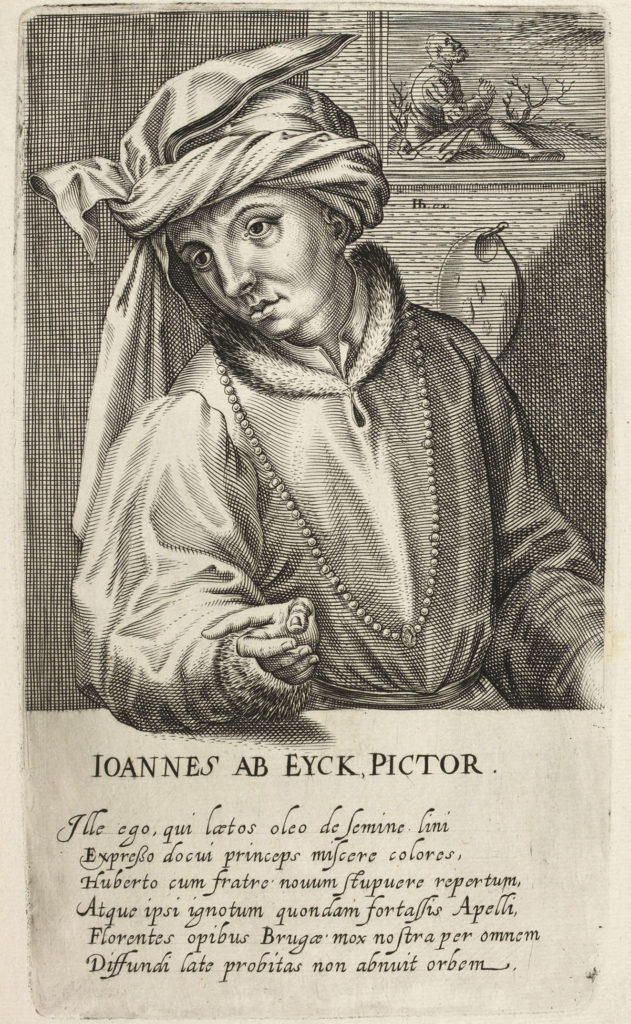

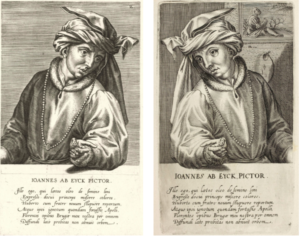

11. Jan Van Eyck

11. Jan Van Eyck

Engraving

Signed 'Hh ex.' by Hendrick Hondius

Copy in reverse direction to Cock 1572 engraved Pictorum

20.7 x 11.9 cm

Transcription of Inscription [Lampsonius]:

IOANNES AB EYCK, PICTOR.

Ille ego, qui laetos oleo de semine lini

Expresso docui princeps miscere colores,

Huberto cum fratre novum stupuere repertum,

Atque ipsi ignotum quondam fortassis Apelli,

Florentes opibus Brugae mox nostra per omnem

Diffundi late probitas non abnuit orbem.

Translation of Inscription [Lampsonius]:

Jan van Eyck, painter

I am he who 12 first taught to mix joyful colours from the pressed oily seed of flax, 13 with my brother Hubert. Bruges, flourishing with wealth, was astounded by this new discovery, perhaps unknown in the past to Apelles himself. Soon afterwards our uprightness 14 did not refuse to be spread widely through the whole world.

Hollstein 1994 no. 83

Karel Van Mander's biography of Jan van Eyck

Grove Art Online biography

View the 1572 print

View the 1572 print

View both prints side by side

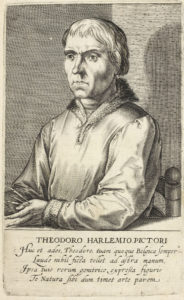

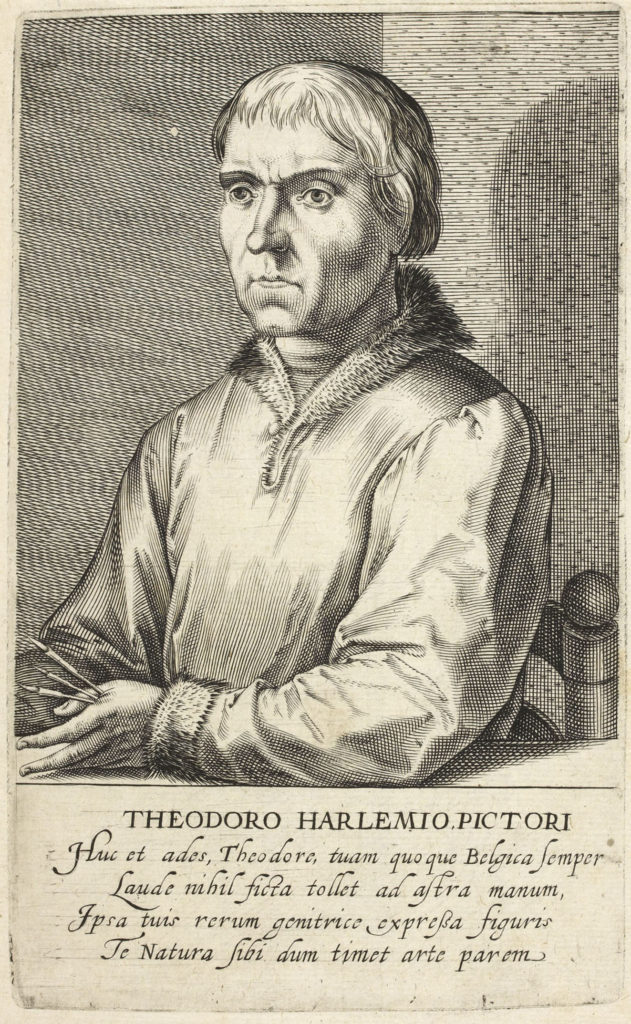

13. Dirck Bouts

13. Dirck Bouts

Engraving

Attributed to Hendrick Hondius

Copy in reverse direction to Cock 1572 engraved Pictorum

19.2 x 11.8 cm

Transcription of Inscription [Lampsonius]:

THEODORO HARLEMIO PICTORI

Huc et ades, Theodore, tuam quoque Belgica semper

Laude nihil ficta tollet ad astra manum,

Ipsa tuis rerum genitrice expressa figuris

Te Natura sibi dum timet arte parem

Translation of Inscription [Lampsonius]:

To Dirck Bouts, painter

You are here too, Theodore. Belgium shall always also raise your hand to the stars with no false praise, while Nature, expressed by your figures, fears you, equal to her in the art of begetting things. 15

Hollstein 1994 no. 84

View the 1572 print

View both prints side by side

15. Hieronymus Bosch

15. Hieronymus Bosch

Engraving, second state.

Signed 'Hh ex.' by Hendrick Hondius

Copy in reverse direction as Cock 1572 engraved Pictorum

19.8 x 12.0 cm

Transcription of Inscription [Lampsonius]:

HIERONIMO BOSCHIO PICTORI.

Quid sibi vult, Hironyme Boschi,

Ille oculus tuus attonitus? quid

Pallor in ore? velut lemures si

Spectra Erebi volitantia coram

Aspiceres? Tibi Ditis avari

Crediderim patuisse recessus

Tartareasque domos tua quando

Quicquid habet sinus imus Averni

Tam potuit bene pingere dextra.

Translation of Inscription [Lampsonius]:

To Hieronymus Bosch, painter.

What is meant by that astonished eye of yours, Hieronymus Bosch, or that pallor in your face? As if you had seen ghosts, the spectres of Erebus, flittering in front of you. I could believe that the caves of greedy Pluto and the houses of Tartarus lay open to you, seeing as your hand could paint so well whatever the lowest hollows of Avernus 16 contain.

Hollstein 1994 no. 85

Karel Van Mander's biography of Hieronymus Bosch.

Grove Art Online biography.

View the 1572 print

View both prints side by side

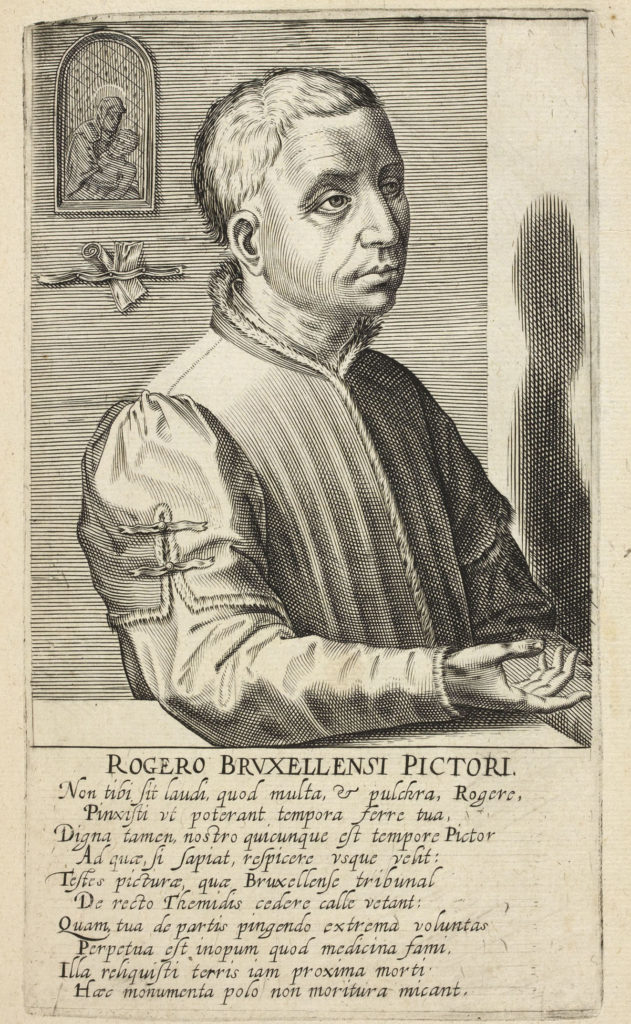

17. Rogier Van Der Weyden

17. Rogier Van Der Weyden

Engraving

Attributed to Hendrick Hondius

Copy in same direction as Cock 1572 engraved Pictorum

21.0 x 12.1 cm

Transcription of Inscription [Lampsonius]:

ROGERO BRUXELLENSI PICTORI.

Non tibi sit laudi, quod multa, et pulchra, Rogere,

Pinxisti ut poterant tempora ferre tua,

Digna tamen, nostro quicunque est tempore Pictor

Ad quae, si sapiat, respicere usque velit :

Testes picturae, quae Bruxellense tribunal

De recto Themidis cedere calle vetant :

Quam tua de partis pingendo extrema voluntas

Perpetua est inopum quod medicina fami.

Illa reliquisti terris iam proxima morti ;

Haec monumenta polo non moritura micant.

Translation of Inscription [Lampsonius]:

To Rogier van der Weyden, painter.

May your praise not be that you painted many beautiful things, as your age could bear them 17 (although they are worthy that anyone who is a painter in our time wish greatly to look at them, if he be wise – the paintings which forbid the tribunal of Brussels to leave the straight path of Justice are witness [to this]): but rather that your last will is a perpetual remedy for the hunger of the poor from the proceeds of your painting. The former, [itself] already near to death, you left on earth; the latter shines in the sky, as a monument that will not die.18

Hollstein 1994 no. 86

Karel Van Mander's biography of Rogier van der Weyden

Grove Art Online biography

View the 1572 print

View both prints side by side

19. Bernaert Van Orley

19. Bernaert Van Orley

Engraving, second state

Signed 'Hh ex.' by Hendrick Hondius

Copy in reverse direction to Cock 1572 engraved Pictorum

20.1 x 12.0 cm

Transcription of Inscription [Lampsonius]:

DE BERNARDO BRUXELLENSI. PICTORE.

Aulica quod sese Bernardo iactet alumno

Bruxella, Attalicas doctissima pingere vestes :

Non tam pictoris, si quis me iudice certet,

Arti debetur, quanquam debetur et arti

Quam tibi quod carus Belgarum Margari rectrix

Dum tibi Appellea nihil est iucundius arte,

Aurea peniculis te dante manubria, et aureos

Saepe tulit, cusum paulo ante numisma, Philippos

Translation of Inscription [Lampsonius]:

About Bernaert van Orley, painter.

That the Court of Brussels boasts of its nursling Bernaert, most skilled19 in painting Attalian20 garments, is not so much due (if anyone wants to argue while I am judging21) to the painter’s skill (although it is also due to his skill) as it is to [the fact] that he was dear to you, Margaret ruler of the Belgians, since nothing is more delightful to you than the art of Apelles. By your gift, he often got golden handles for his paintbrushes, and gold coins, in recently minted currency.

Hollstein 1994 no. 87

Karel Van Mander's biography of Bernaert van Orley

Grove Art Online biography

View the 1572 print

View both prints side by side

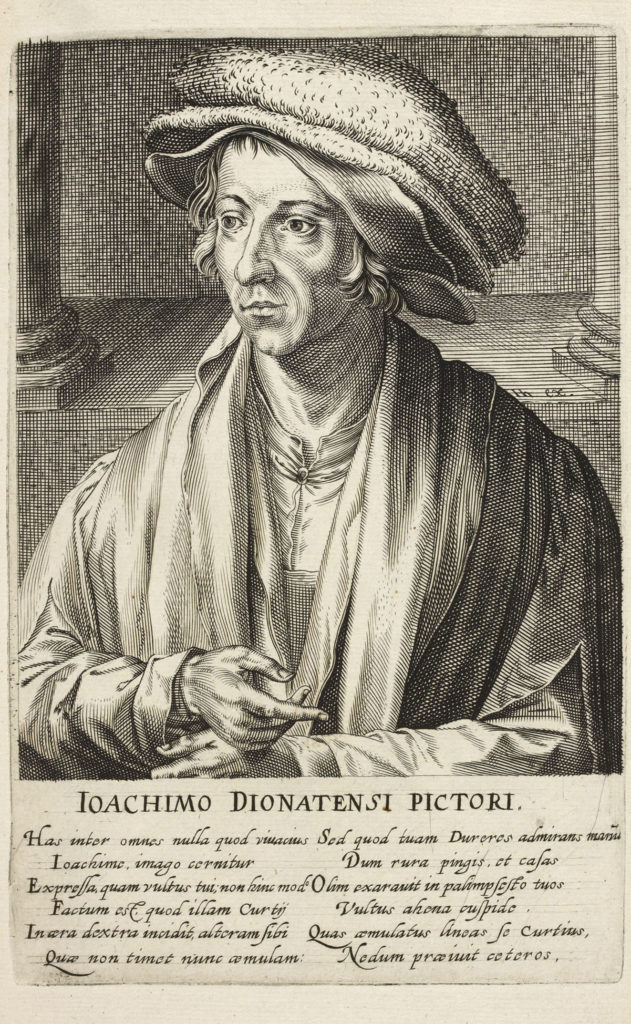

21. Joachim Patinir

21. Joachim Patinir

Engraving

Signed 'Hh ex.' by Hendrick Hondius

Copy in reverse direction to Cock 1572 engraved Pictorum

19.1 x 12.3 cm

Transcription of Inscription [Lampsonius]:

IOACHIMO DIONATENSI PICTORI.

Has inter omnes nulla quod vivacius

Ioachime, imago cernitur

Expressa, quam vultus tui ; non hinc modo

Factus est, quod illam Curtii

In aera dextra incidit, alteram sibi

Quae non timet nunc aemulam :

Sed quod tuam Dureres admirans manum

Dum rura pingis, et casas

Olim exaravit in palimpsesto tuos

Vultus ahena cuspide.

Quas aemulatus lineas se Curtius,

Nedum praeivit ceteros.

Translation of Inscription [Lampsonius]:

To Joachim Patenir, painter.

That, amongst all of these, no image expressed with more liveliness than your face is to be seen, Joachim, has happened not only because Curtius'22 hand cut it into the bronze ([the hand] which does not now fear another rival), but [also] because Dürer, admiring your hand, when you painted fields and huts,23 once drew your face on a palimpsest24 with his bronze point. Imitating those lines, Curtius surpassed himself, not to mention all the others.

Hollstein 1994 no. 88

Karel Van Mander's biography of Joachim Patinir

Grove Art Online biography

View the 1572 print

View both prints side by side

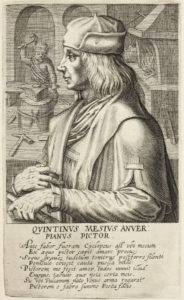

23. Quentin Matsys

23. Quentin Matsys

Engraving

Signed 'Hh ex.' by Hendrick Hondius

Copy in same direction as Cock 1572 engraved Pictorum

20.4 x 12.0 cm

Transcription of Inscription [Lampsonius]:

QUINTINUS MESIUS. ANVER:PIANUS PICTOR.

Ante faber fueram Cyclopeus ; ast ubi mecum

Ex aequo pictor coepit amars25 procus :

Seque graves tuditum tonitrus postferre silenti

Peniculo obiecit cauta puella mihi :

Pictorem me fecit amor. tudes innuit illud

Exiguus, tabulis quae nota certa meis,

Sic ubi Vulcanum nato Venus arma rogarat

Pictorem e fabro summe Poeta facis.

Translation of Inscription [Lampsonius]:

To Quentin Matsys, painter of Antwerp.

Before I used to be a Cyclopean smith,26 but when a wooing painter began to love27 on an equal footing with me, and the cautious girl objected to me that she liked the heavy thundering of hammers less than the silent paintbrush, love made me a painter. A tiny hammer, which is the sure note of my paintings, alludes to this. Thus, when Venus had asked Vulcan for arms for her son, you, greatest of poets, made a painter out of a smith.28

Hollstein 1994 no.89

Karel Van Mander's biography of Quentin Matsys

Grove Art Online biography

View the 1572 print

View both prints side by side

25. Cornelius Engebrechtsz

25. Cornelius Engebrechtsz

Engraving

Signed 'Hh exc.' by Hendrick Hondius

20.5 x 12.4 cm

Transcription of Inscription [Lampsonius]:

CORNELIUS ENGELBERT. LEIDAN. PICTOR.

Hic inter primos oleo de semine lini

Expresso in Batavis pingere qui didicit.

Miramur Vultus quos pinxit, Chromata laeta.

Pictorum hunc Lucas flos colit artificem.

Translation of Inscription [Lampsonius]:

Cornelis Engelbrechtsz. Painter of Leyden.

This man was among the first of the Dutch who learnt to paint with pressed oily seed of flax.29 We wonder at the faces [and] joyful colours which he painted. Lucas, the flower of painters, frequented this artist.

Hollstein 1994 no.90

Karel Van Mander's biography of Cornelius Engebrechtsz

Grove Art Online biography

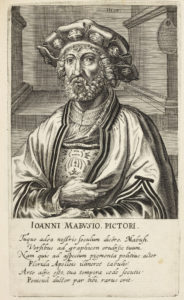

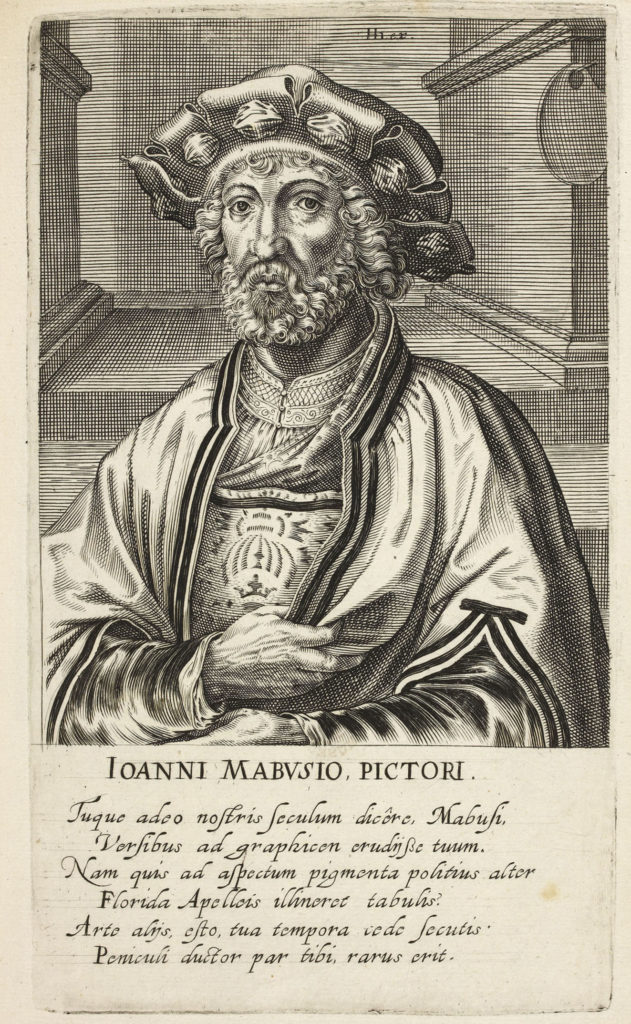

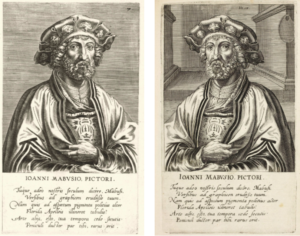

27. Jan Gossaert, called Mabuse

27. Jan Gossaert, called Mabuse

Engraving, second state

Signed 'Hh ex.' by Hendrick Hondius

Copy in reverse direction as Cock 1572 engraved Pictorum

20.9 x 12.2 cm

Transcription of Inscription [Lampsonius]:

IOANII MABUSIO, PICTORI.

Tuque adeo nostris seculum dicêre, Mabusi,

Versibus ad graphicen erudiisse tuum.

Nam quis ad aspectum pigmenta politius alter

Florida Apelleis illineret tabulis?

Arte aliis, esto, tua tempora cede secutis ;

Peniculi ductor par tibi, rarus erit.

Translation of Inscription [Lampsonius]:

To Jan Gossaert, painter.

You too, indeed, man of Maubeuge, will be said in our verses to have educated your age in drawing. For who else could daub Apelles’ boards30 with flowering pigments smoother to the eye? Granted, you yield in skill to others who followed your age. [But] rare will be the guider of the brush who is equal to you.

Hollstein 1994 no.91

Karel Van Mander's biography of Jan Gossaert

Grove Art Online biography

View the 1572 print

View both prints side by side

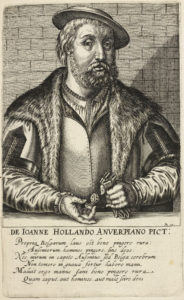

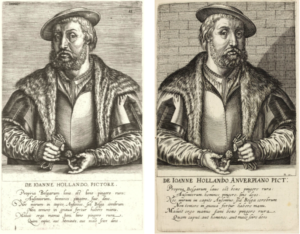

29. Jan van Amstel

29. Jan van Amstel

Engraving

Signed 'Hh ex.' by Hendrick Hondius

Copy in reverse direction as Cock 1572 engraved Pictorum

20.1 x 12.3 cm

Transcription of Inscription [Lampsonius]:

DE JOANNE HOLLANDO, ANVERPIANO PICT :

Propria Belgarum laus est bene pingere rura :

Ausoniorum, homines pingere, sine31 deos.

Nec mirum in capite Ausonius, sed Belga cerebrum

Non temere in guava32 fertur habere manu.

Maluit ergo manus Jani bene pingere rura

Quam caput, aut homines, aut male scire deos.

Translation of Inscription [Lampsonius]:

To Jan van Amstel, painter of Antwerp 33

The proper praise of Belgians is to paint fields well; that of Italians to paint men or gods. Nor is it surprising: not without reason is the Italian said to have his brain in his head, [while] the Belgian [has his] in his active hand. Jan’s hand, then, preferred to paint fields well, than for his head to know poorly either men or gods.

Hollstein 1994 no.92

Karel Van Mander's biography of Jan van Amstel

Grove Art Online biography

View the 1572 print

View both prints side by side

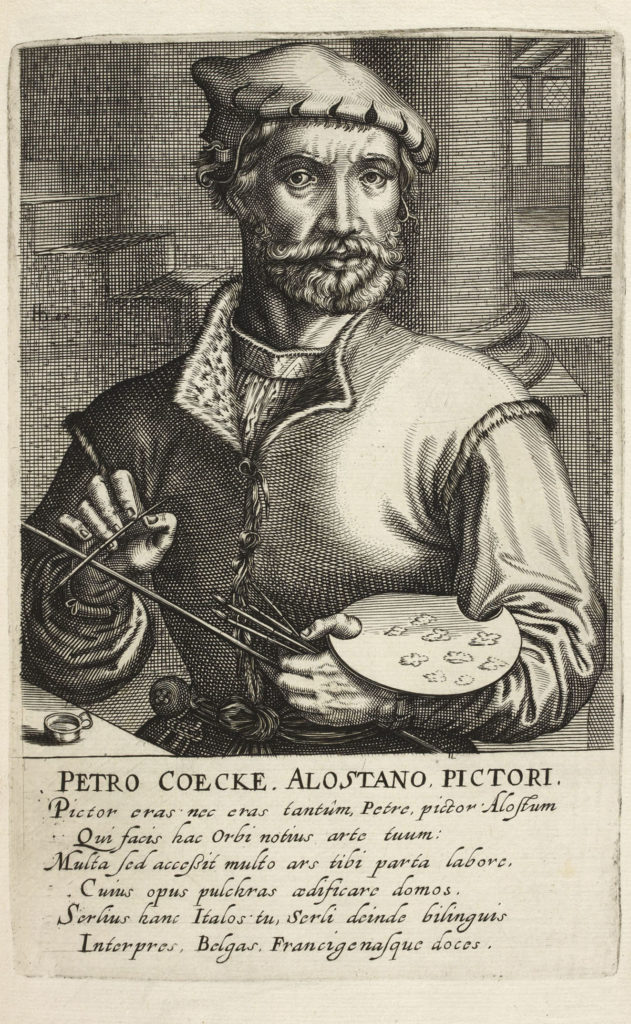

31. Pieter Coecke van Aelst

31. Pieter Coecke van Aelst

Engraving

Signed 'Hh ex.' by Hendrick Hondius

Copy in same direction as Cock 1572 engraved Pictorum

19.3 x 12.6 cm

Transcription of Inscription [Lampsonius]:

PETRO COECKE. ALOSTANO, PICTORI.

Pictor eras nec eras tantûm, Petre, pictor ; Alostum

Qui facis hac Orbi notius arte tuum :

Multa sed accessit multo ars tibi parta labore,

Cuius opus pulchras aedificare domos.

Serlius hanc Italos ; tu, Serli deinde bilinguis

Interpres, Belgas, Francigenasque doces.

Translation of Inscription [Lampsonius]:

To Pieter Coecke van Aelst, painter.

You were a painter, but, Pieter, you were not only a painter, you who made your Aelst34 more known to the world by this skill. But there was much skill in addition, born to you by much labour. Its office was to build beautiful houses. Serlio taught this to the Italians, then you, bilingual interpreter of Serlio, taught the Belgians and the French.

Hollstein 1994 no.93

Karel Van Mander's biography of Pieter Coecke van Aelst

Grove Art Online biography

View the 1572 print

View both prints side by side

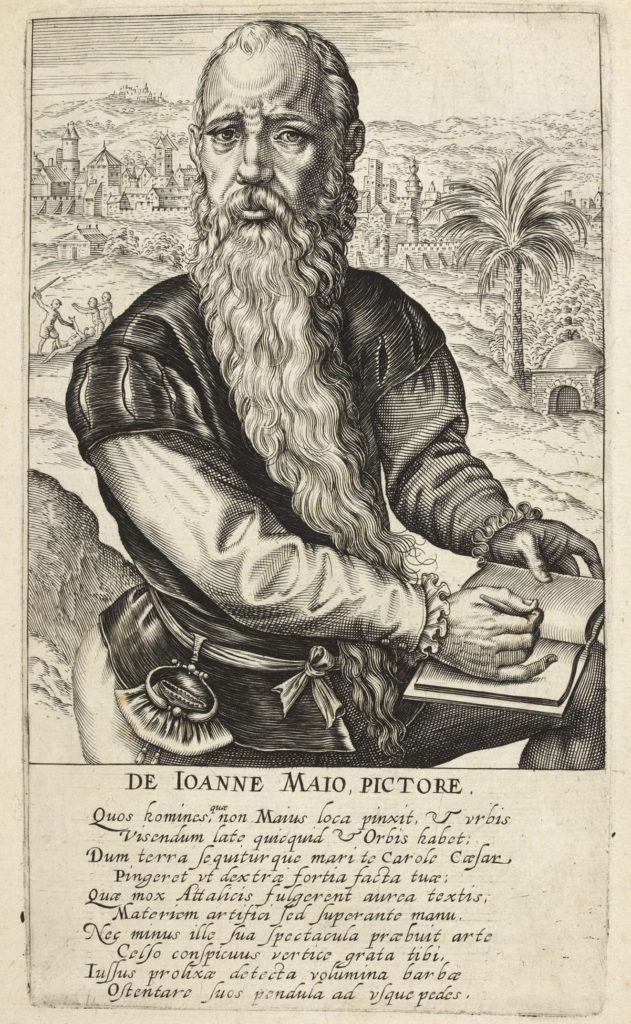

33. Jan Vermeyen

33. Jan Vermeyen

Engraving

Attributed to Hendrick Hondius

Copy in reverse direction to Cock 1572 engraved Pictorum

20.6 x 11.8 cm

Transcription of Inscription [Lampsonius]:

DE IOANNE MAIO, PICTORE.

Quos homines, quae non Maius loca pinxit, et urbis35

Visendum late quicquid et Orbis habet ;

Dum terra sequiturque mari te Carole Caesar

Pingeret ut dextrae fortia facta tuae ;

Quae mox Attalicis fulgerent aurea textis,

Materiem artifici sed superante manu.

Nec minus ille sua spectacula praebuit arte

Celso conspicuus vertice grata tibi,

Iussus prolixae detecta volumina barbae

Ostentare suos pendula ad usque pedes.

Translation of Inscription [Lampsonius]:

About Jan Vermeyen, painter.

What men, what places and what cities36 has Vermeyen not painted? –– and whatever the world, far and wide, has worth seeing - while he followed you on land and sea, Emperor37 Charles, to paint the mighty deeds of your hand. These soon shone in gold with Attalian38 embroidery, although the artist’s hand was greater than the material.39 Nor did he provide a sight less pleasing to you than his art – [he was] remarkable for his high forehead, [and] was ordered to show off the unhidden folds of his rich beard, hanging down to his feet.

Hollstein 1994 no.94

Karel Van Mander's biography of Jan Vermeyen

Grove Art Online biography

View the 1572 print

View both prints side by side

35. Mathys Cock

35. Mathys Cock

Engraving

Attributed to Hendrick Hondius

Copy in reverse direction to Cock 1572 engraved Pictorum

19.6 x 12.4cm

Transcription of Inscription [Lampsonius]:

MATTHIÆ COCO ANVERPIAN. PICTORI. HIERONYMI FRATRI.

Tu quoque, Matthia, sic pingere rura sciebas,

Ut tibi vix dederint tempora nostra parem.

Ergo, quod artifices inter spectaris et ipse,

Quos immortalis40 Belgica laude colit ;

Non in te pietas tantem41 fraterna, sed arti

Efficit et merito laus tribuenda tuae.

Translation of Inscription [Lampsonius]:

To Matthias Cock of Antwerp, painter, brother of Hieronymus.

You too, Matthias, knew how to paint fields in such a way, that our age has scarcely produced your equal. Therefore, if you too are considered among the artists whom Belgium honours with immortal42 praise, not only43 fraternal piety grants this to you, but also the praise justly due to your skill.

Hollstein 1994 no.95

Karel Van Mander's biography of Mathys Cock

Grove Art Online biography

View the 1572 print

View both prints side by side

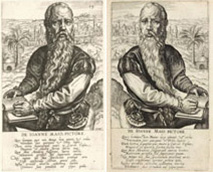

37. Henri Met de Bles

37. Henri Met de Bles

Engraving, second state

Signed 'Hh ex.' by Hendrick Hondius

Copy in reverse direction to Cock 1572 engraved Pictorum

20.6 x 12.3 cm

Transcription of Inscription [Lampsonius]:

HENRICO BLESIO, BOVINATI, PICTORI.

Pictorem urbs dederat Dionatum Eburonia, pictor

Quem proximis dixit poeta versibus

Illum adeo artificem patriae situs ipse, magistro

Aptissimus, vix edocente fecerat.

Hanc laudem invidit vicinae exile Bovinum,

Et rura doctum pingere Henricum dedit

Sed quantum cedit Dionato exile Bovinum

Ioachime, tantum cedit Henricus tibi.

Translation of Inscription [Lampsonius]:

To Herri met de Bles of Bouviges, painter.

The Eburonian city44 had produced the painter of Dinant, the painter of whom the poet spoke in recent verses. The most favourable site of his homeland had made him entirely an artist, and a master hardly taught him. Tiny Bouviges was jealous of this its neighbour’s glory and produced Hendrik, learned in painting fields. But, Joachim, as much as tiny Bouviges yields to Dinant [in size], so much does Hendrik yield to you.

Hollstein 1994 no.96

Karel Van Mander's biography of Henri met de Bles

Grove Art Online biography

View the 1572 print

View both prints side by side

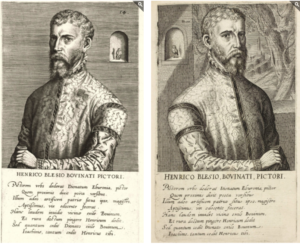

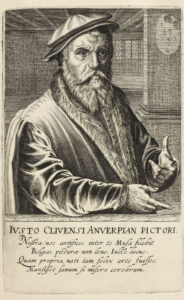

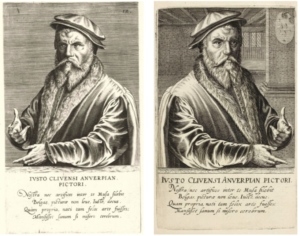

39. Joos van Cleve

39. Joos van Cleve

Engraving

Signed 'Hh' by Hendrick Hondius

Copy in reverse direction to Cock 1572 engraved Pictorum

19.3 x 12.1 cm

Transcription of Inscription [Lampsonius]:

IUSTO CLIVENSI ANVERPIAN PICTORI.

Nostra nec artifices inter te Musa silebit

Belgas, picturae non leve, Iuste, decus.

Quam propria, nati tam felix arte fuisses ;

Mansisset sanum si misero cerebrum.

Translation of Inscription [Lampsonius]:

To Joos van Cleve of Antwerp, painter.

Our muse shall not keep silent about you, among the Belgian artists, Joos, [you who are ] no trivial glory of painting. You would have been as happy in your son’s art as in your own, if only the wretch’s brain had remained healthy.

Hollstein 1994 no. 97

Karel Van Mander's biography of Joos van Cleve

Grove Art Online biography

View the 1572 print

View both prints side by side

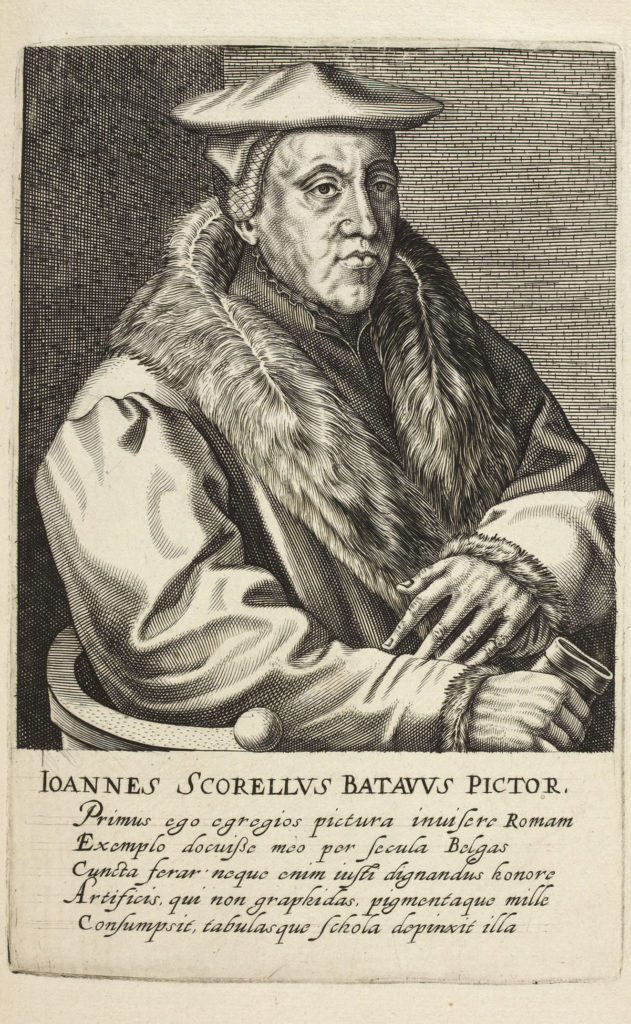

41. Jan van Scorel

41. Jan van Scorel

Engraving, second state

Attributed to Hendrick Hondius

Copy in reverse direction to Cock 1572 engraved Pictorum

19.5 x 12.7 cm

Transcription of Inscription [Lampsonius]:

IOANNES SCORELLUS BATAVUS PICTOR.

Primus ego egregios pictura invisere Romam

Exemplo docuisse meo per secula Belgas

Cuncta ferar ; neque enim iusti dignandus honore

Artificis, qui non graphidas, pigmentaque mille

Consumpsit, tabulasque schola depinxit illa45

Translation of Inscription [Lampsonius]:

Jan van Scorel, Dutch painter.

Through all centuries I shall be said to have been the first to have taught by my example the excellent Belgians to be envious of Rome in painting. For he is not worthy of the honour of a true artist, who does not use up a thousand pencils and pigments, and paint pictures in that school.46

Hollstein 1994 no.98

Karel Van Mander's biography of Jan van Scorel

Grove Art Online biography

View the 1572 print

View both prints side by side

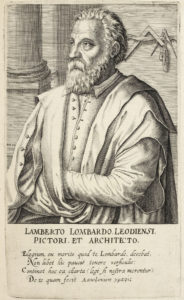

43. Lambert Lombard

43. Lambert Lombard

Engraving, second state

Signed 'Hh ex.' by Hendrick Hondius

Copy in same direction as Cock 1572 engraved Pictorum

20.1 x 11.9 cm

Transcription of Inscription [Lampsonius]:

LAMBERTO LOMBARDO, LEODIENSIS PICTORI. ET ARCHITECTO.

Elogium, ex merito quod te, Lombarde, decebat,

Non libet hîc paucis texere versiculis :

Continet hoc ea charta (legi si nostra merentur)

De te quam fecit Λαμψονίοτε γραφίς

Translation of Inscription [Lampsonius]:

To Lambert Lombard of Liège, painter and architect

It does not please [me], Lombard, to write here in a few verses an epigraph which would be suitable to your merits. Those pages contain it which (if our works deserve to be read) the Lampsonian pen47 wrote about you.

Hollstein 1994 no. 99

Karel Van Mander's biography of Lambert Lombard

Grove Art Online biography

View the 1572 print

View both prints side by side

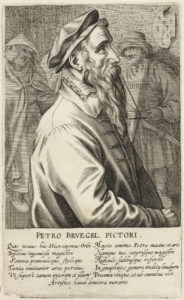

45. Pieter Bruegel

45. Pieter Bruegel

Engraving, second state

Signed 'Hh' by Hendrick Hondius

Copy in reverse direction to Cock 1572 engraved Pictorum

19.2 x 11.7 cm

Transcription of Inscription [Lampsonius]:

PETRO BRVEGEL, PICTORI.

Quis novus hic Hieronymus Orbi

Boschius ? ingeniosa magistri

Somnia peniculoque, styloque

Tanta imitarier arte peritus.

Ut superet tamen interim et illum ?

Macte animo, Petre, mactus ut arte

Namque tuo, veterisque magistri

Ridiculo, salibusque referto

In graphices genere inclita laudum

Praemia ubique, et ab omnibus ullo

Artifice haud leviora mereris

Translation of Inscription [Lampsonius]:

To Pieter Bruegel, painter.

Who is this new Hieronymus Bosch for the world, versed in imitating the master’s ingenious dreams with such great skill of paintbrush and pen – so that sometimes he surpasses even him. Pieter, [you are] blessed in your spirit, as you are blessed in your skill, for in your own and your old master’s comic type of painting, full of wit, you deserve glorious rewards of praise, everywhere and from everyone, no less than those of any artist.

Hollstein 1994 no.100

Karel Van Mander's biography of Pieter Bruegel

Grove Art Online biography

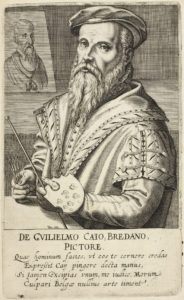

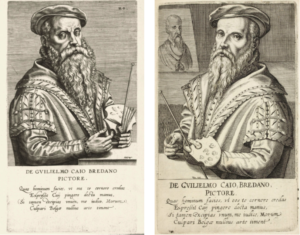

47. Willem Key

47. Willem Key

Engraving

Signed 'Hh ex.' by Hendrick Hondius

Copy in reverse direction to Cock 1572 engraved Pictorum

19.8 x 12.0 cm

Transcription of Inscription [Lampsonius]:

DE GUILIELMO CAIO, BREDANO, PICTORE.

Quas hominum facies, ut eos te cernere credas

Expressit Caii pingere docta manus,

(Si tamen excipias unum, me iudice, Morum)

Culpari Belgae nullius arte timent.

Translation of Inscription [Lampsonius]:

About Willem Key of Breda, painter.

What faces of people the hand of Key, learned in painting, expressed, so that you could believe you were looking at them!48 – if however, you except one, Mor,49 in my opinion the Belgians do not fear to be found wanting because of anyone’s skill.

Hollstein 1994 no.101

Karel Van Mander's biography of William Key

Grove Art Online biography

View the 1572 print

View both prints side by side

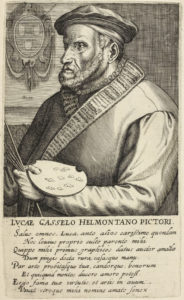

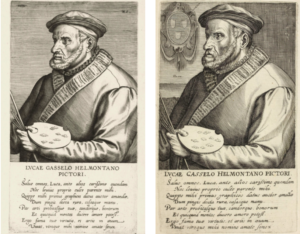

49. Lucas Gassel

49. Lucas Gassel

Engraving, second state

Signed 'Hh ex.' by Hendrick Hondius

Copy in same direction as Cock 1572 engraved Pictorum

20.4 x 12.1 cm

Transcription of Inscription [Lampsonius]:

LUCÆ GASSELO HELMONTANO PICTORI.

Salve omnes, Luca, ante alios carissime quondam

Nec levius proprio culte parente mihi.

Quippe mihi primus graphices datus auctor amandae

Dum pingis docta rura, casasque manu.

Par arte50 probitasque tuae, candorque, bonorum

Et quicquid mentes ducere amore potest.

Ergo fama tuae virtutis, et artis in aevum

Vivat, utroque mihi nomine amate senex

Translation of Inscription [Lampsonius]:

To Lucas Gassel of Helmond, painter.

Hail, Lucas, once more dear than all the rest, and no less honoured by me than my own father. Indeed you were the first cause of loving painting offered to me, while you were painting fields and huts51 with your learned hand. Equal to your skill52 [else] can attract the minds of the good with love. Therefore may the fame of your virtue and skill live forever, old man beloved to me on both counts.

Hollstein 1994 no.102

Karel Van Mander's biography of Lucas Gassel

Grove Art Online biography

View the 1572 print

View both prints side by side

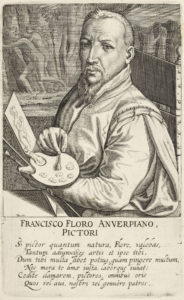

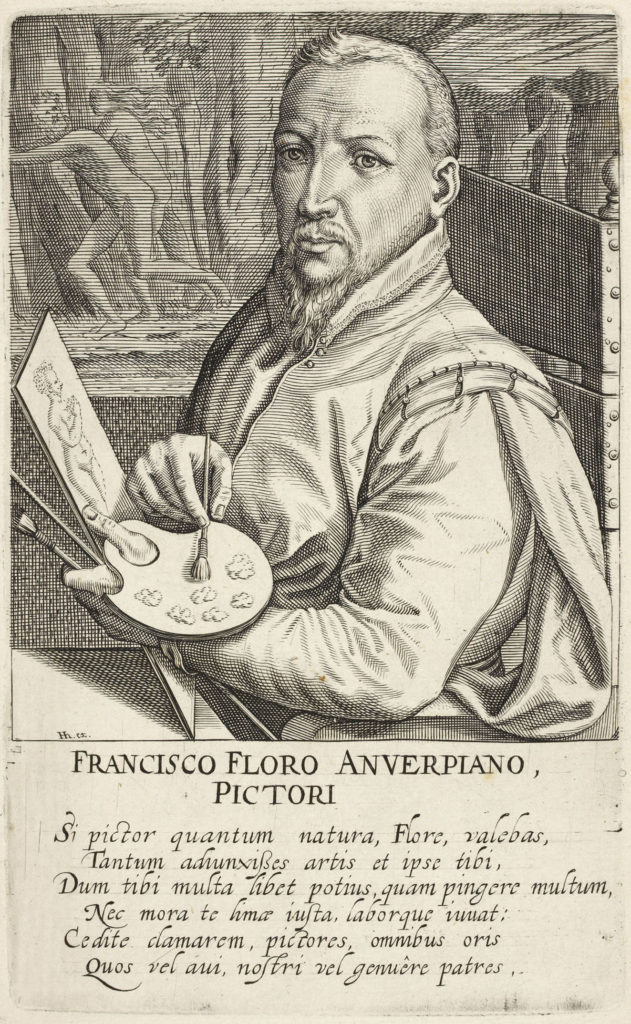

51. Frans Floris

51. Frans Floris

Engraving

Signed 'Hh ex.' by Hendrick Hondius

Copy in same direction as Cock 1572 engraved Pictorum

20.5 x 12.5 cm

Transcription of Inscription [Lampsonius]:

FRANCISCO FLORO ANVERPIANO, PICTORI

Si pictor quantum natura, Flore, valebas,

Tantum adiunxisses artis et ipse tibi,

Dum tibi multa libet potius, quam pingere multum

Nec mora te limae iusta, laborque iuvat :

Cedite clamarem, pictores, omnibus oris

Quos vel avi, nostri vel genuêre patres.

Translation of Inscription [Lampsonius]:

To Frans Floris of Antwerp, painter

If, Floris you had acquired for yourself as much skill as you had natural ability as a painter (since you preferred to paint many things than to paint a lot,53 and neither the just delay of the file nor hard work54 pleased you) – I would cry out ‘yield painters from all lands,55 whom either our grandfathers or our fathers produced’.

Hollstein 1994 no.103

Karel Van Mander's biography of Frans Floris

Grove Art Online biography

View the 1572 print

View both prints side by side

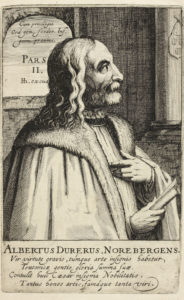

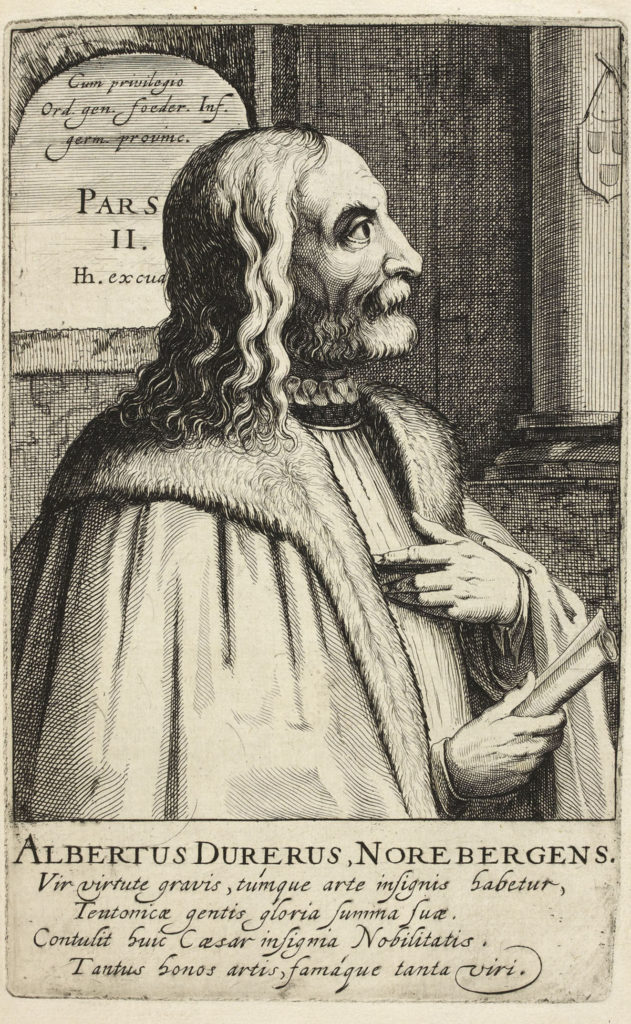

53. Albrecht Dürer

53. Albrecht Dürer

Etching

Signed Hh excud. By Hendrick Hondius, attributed to Simon Frisius

11.8 x 19.4 cm

Transcription of Inscription:

ALBERTUS DURERUS, NOREBERGENS

Vir virtute gravis, túmque arte insignis habetur,

Teutonicae gentis gloria summa suae.

Contulit huic Caesar insignia nobilitatis,

Tantus honos artis, famáque tanta viri.

Translation of Inscription:

Albrecht Dürer of Nuremberg

He is considered to be a man grave in virtue and famous for his skill, the greatest glory of his Teutonic56 people. The emperor57 gave him the marks of nobility. So great was the honour [paid] to his skill, and so great the man’s fame.

Orenstein 1996 Frisius, no. 143; Hollstein 2008 no. 163

Karel Van Mander's biography of Albrecht Dürer

Grove Art Online biography

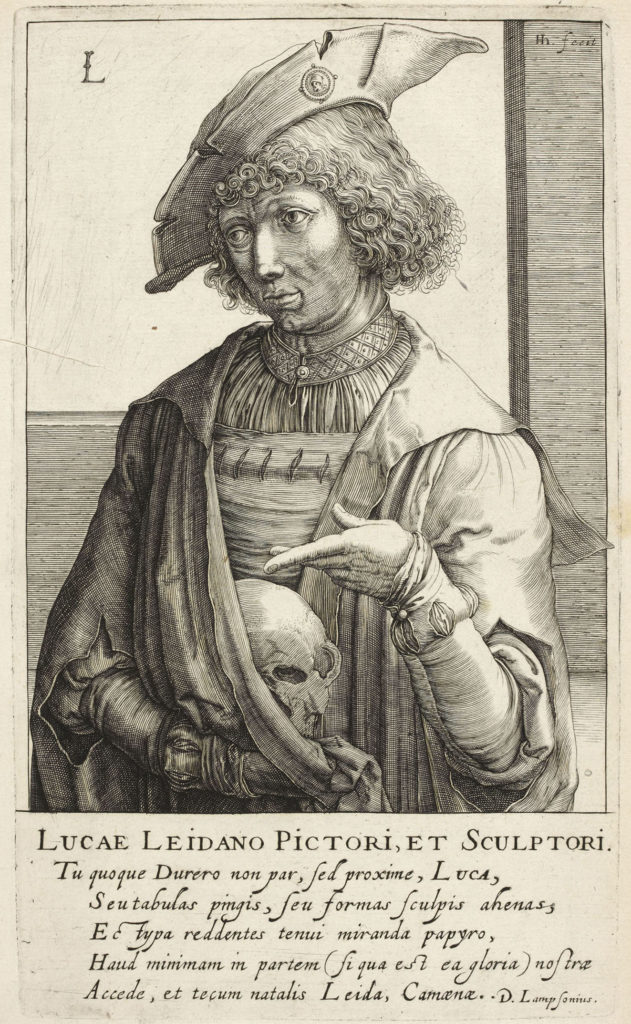

55. Lucas van Leyden

55. Lucas van Leyden

Etching

Signed 'Hh fecit' by Hendrick Hondius

21.9 x 12.9 cm

Transcription of Inscription [Lampsonius]:

LUCÆ LEIDANCO PICTORI, ET SCULPTORI

Tu quoque Durero non par, sed proxime, Luca,

Seu tabulas pingis, seu formas sculpis ahenas,

Ectypa reddentes tenui miranda papyro,

Haud minimam in partem (si qua est ea gloria) nostrae

Accede, et tecum natalis Leida, Camoenae.

D. Lampsonius.

Translation of Inscription:

To Lucas van Leyden, painter and sculptor58

You too, not equal, but nearest to Dürer, whether you be painting pictures, or sculpting bronze forms which provide marvellous plates for the thin paper, take (if there is any glory in this)59 a place – not the least important – in our Muse’s work,60 along with your native Leyden.

D. Lampsonius

View the 1572 print

View both prints side by side

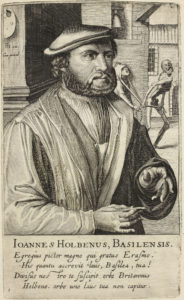

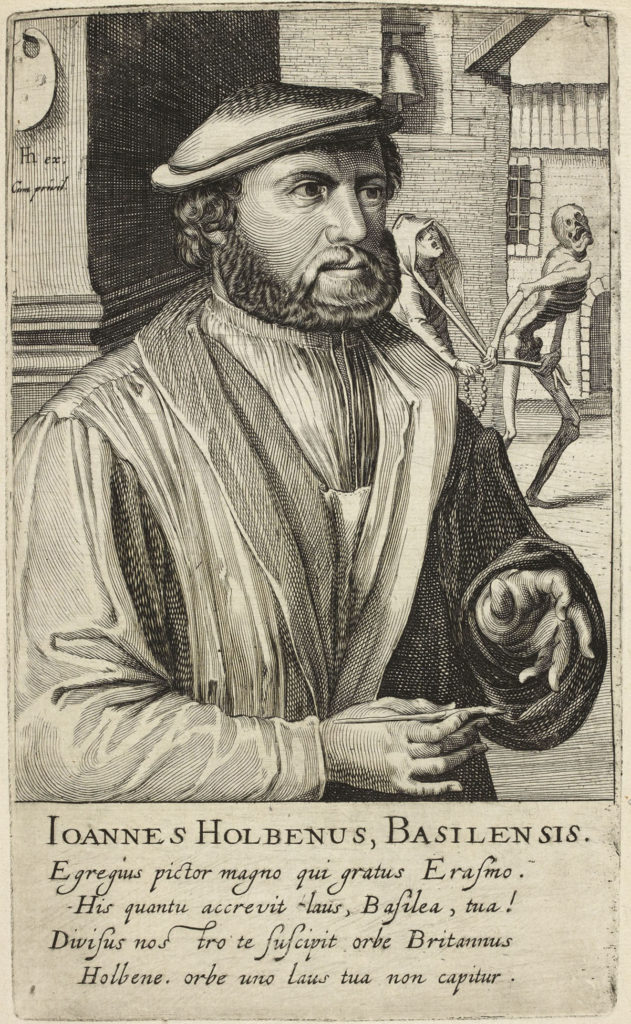

57. Hans Holbein

57. Hans Holbein

Etching

Signed Hh ex. by Hendrick Hondius, attributed to Simon Frisius

20.5 x 12.3 cm

Transcription of Inscription:

IOANNES HOLBENUS, BASILENSIS

Egregius pictor magno qui gratus Erasmo.

His quantu61 accrevit laus, Basilea, tua !

Divisus nostro te suscipit orbe Britannus

Holbene. orbe uno laus tua non capitur.

Translation of Inscription:

Hans Holbein of Basel

An exceptional painter, who was pleasing to great Erasmus. From this, Basel, how much does62 your praise grow! The Briton, separated from our world,63 received you, Holbein. Your praise is not contained by one world.

Orenstein 1996, Frisius no. 148; Hollstein 2008 no. 168

Karel Van Mander's biography of Hans Holbein

Grove Art Online biography

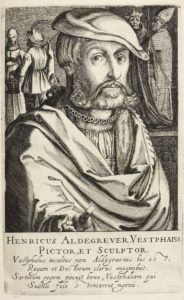

59. Heinrich Aldegrever

59. Heinrich Aldegrever

Etching and engraving

Signed 'Hh' by Hendrick Hondius, attributed to Simon Frisius

20.4 x 12.7 cm

Transcription of Inscription:

HENRICUS ALDEGREVER, VESTPHALUS. PICTOR, ET SCULPTOR

Vestphalus incultus non Aldegravius hic est,

Regum et Doctorum clarus imaginibus.

Sartorem rege pinxit bene, Vestphaliam qui

Subtili filo strinxerat ingenii.

Translation of Inscription:

Heinrich Aldegrever, the Westphalian, painter and sculptor

This Aldegrever is not an uneducated Westphalian. He was famous for images of kings and learned men. He painted well the tailor king,64 he who had bound Westphalia with the subtle thread of his genius.

Orenstein 1996, Frisius no. 136; Hollstein 2008 no. 156

Karel Van Mander's biography of Heinrich Aldegrever

Grove Art Online biography

61. Jacob Binck

61. Jacob Binck

Etching

Signed 'Hh' by Hendrick Hondius, attributed to Simon Frisius

20.2 x 12.2 cm

Transcription of Inscription:

IACOBUS BINCKIUS, GERMAN. PICT. ET SCULP.

Binckius, ingenio quae finxit, pinxit et idem,

Et scalpsit. certant ars, manus, ingenium.

Cúm tua sint docté parvis expressa tabellis ;

Artis Censori credito magnus eris.

Translation of Inscription:

Jacob Binck, German painter and sculptor

Binck painted and engraved himself what he imagined in his mind.65 His skill, hand and mind vie [with one another]. Since your [works] are learnedly expressed,66 you will be great, if the censor of skill is believed.67

Orenstein 1996, Frisius, no. 137; Hollstein 2008 no.157

Grove Art Online biography

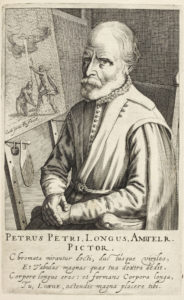

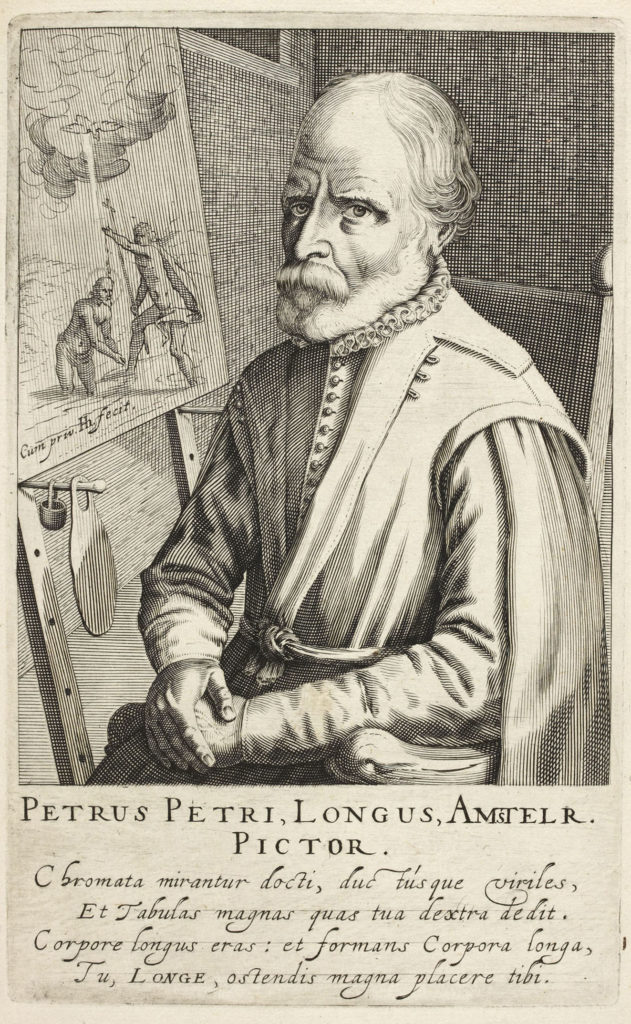

63. Pieter Aertsen

63. Pieter Aertsen

Engraved by Hendrick Hondius (Orenstein 1996)

Signed 'Hh fecit' by Hendrick Hondius

20.2 x 12.6 cm

Transcription of Inscription:

PETRUS PETRI, LONGUS, AMSTELR. PICTOR.

Chromata mirantur docti, ductúsque viriles,

Et Tabulas magnas quas tua dextra dedit.

Corpore longus eras : et formans Corpora longa,

Tu, LONGE, ostendis magna placere tibi.

Translation of Inscription:

Pieter Aertsen, the Long of Amsterdam, painter.

The learned wonder at your colours, your manly strokes, and the great paintings which your hand produced. You were long in body, and made long bodies: Long one, you have shown that great things please you.

Hollstein 1994 no.105

Karel Van Mander's biography of Pieter Aertsen

Grove Art Online biography

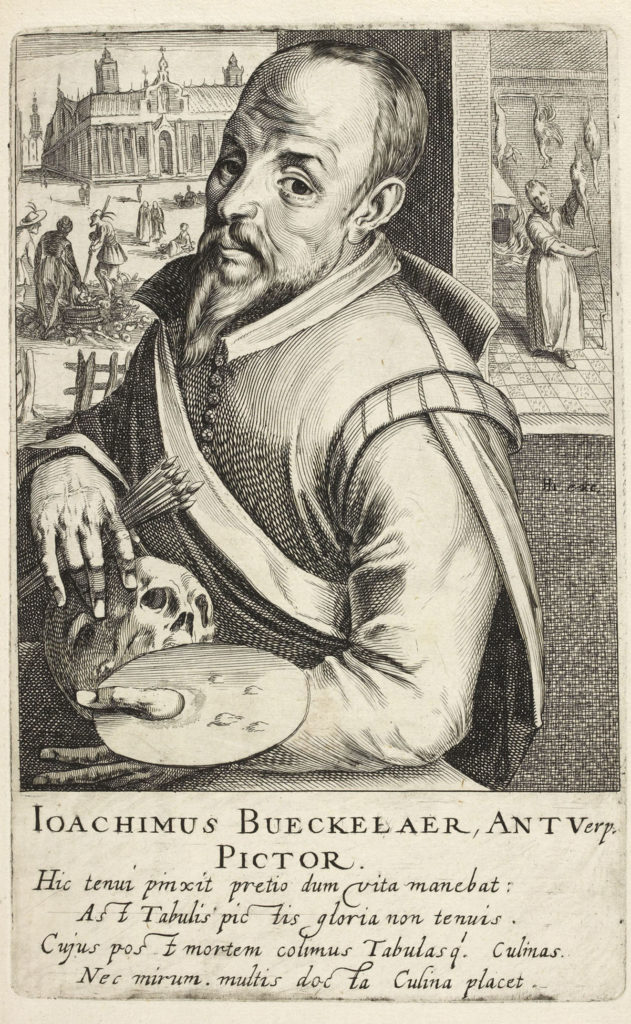

65. Joachim Beuckelaer

65. Joachim Beuckelaer

Etching

Signed 'Hh exc.' by Hendrick Hondius, attributed to Simon Frisius

19.5 x 12.2 cm

Transcription of Inscription:

IOACHIMUS BUECKELAER, ANTVERP. PICTOR

Hic tenui pinxit pretio dum vita manebat :

Ast Tabulis pictis gloria non tenuis.

Cujus post mortem colimus tabulasque culinas.68

Nec mirum. multis docta culina placet.

Translation of Inscription:

Joachim Beuckelaer of Antwerp, painter

This man painted for a meagre reward, while life remained [to him].69 But his pictures have no meagre glory, whose paintings and kitchens70 we honour after his death. Nor is this surprising. A learned kitchen pleases many.

Orenstein 1996 no. 140; Hollstein 2008 no. 160

Karel Van Mander's biography of Joachim Beuckelaer

Grove Art Online biography

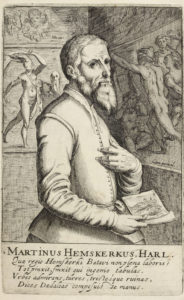

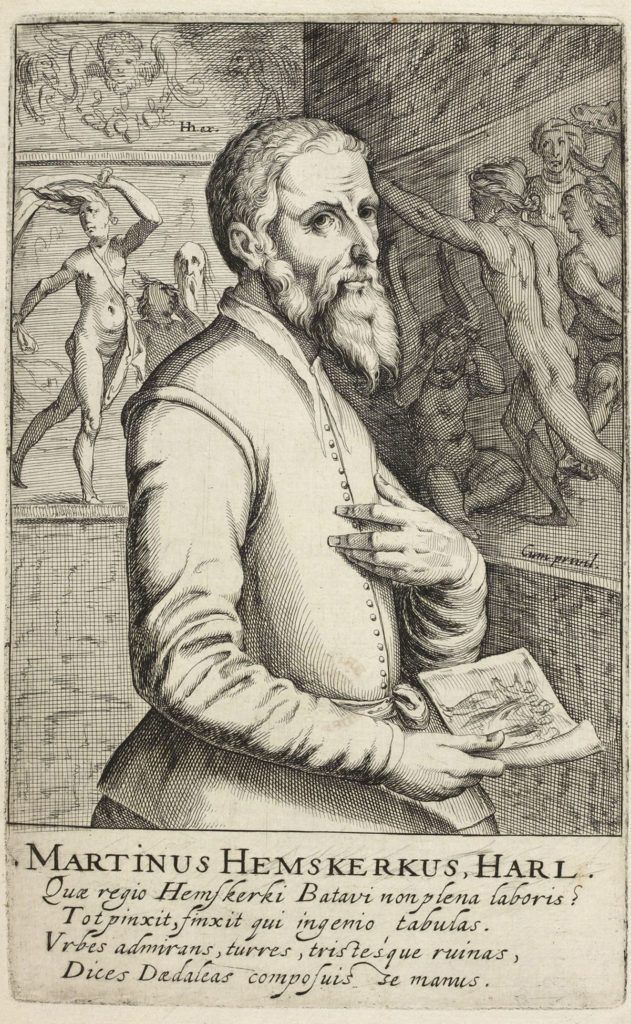

67. Maarten van Heemskerk

67. Maarten van Heemskerk

Etching

Signed 'Hh ex.' by Hendrick Hondius, attributed to Simon Frisius

19.7 x 12.3 cm

Transcription of Inscription:

MARTINUS HEMSKERKUS, HARL.

Quae regio, Hemskerki Batavi non plena laboris?

Tot pinxit, finxit qui ingenio tabulas.

Urbes admirans, turres, tristeśque ruinas,

Dices Daedaleas composuisse manus.

Translation of Inscription:

Maarten van Heemskerck of Haarlem

What region is not full of the labour of Maarten the Dutchman,71 who painted and made so many pictures with his genius?72 Admiring cities, towers, and sad ruins, you will say that the hands of Daedalus made them.

Orenstein 1996, Frisius no. 146; Hollstein 2008 no. 166

Karel Van Mander's biography of Maarten van Heemskerck

Grove Art Online biography

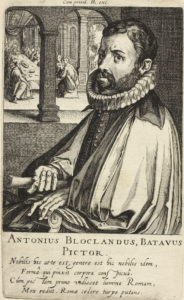

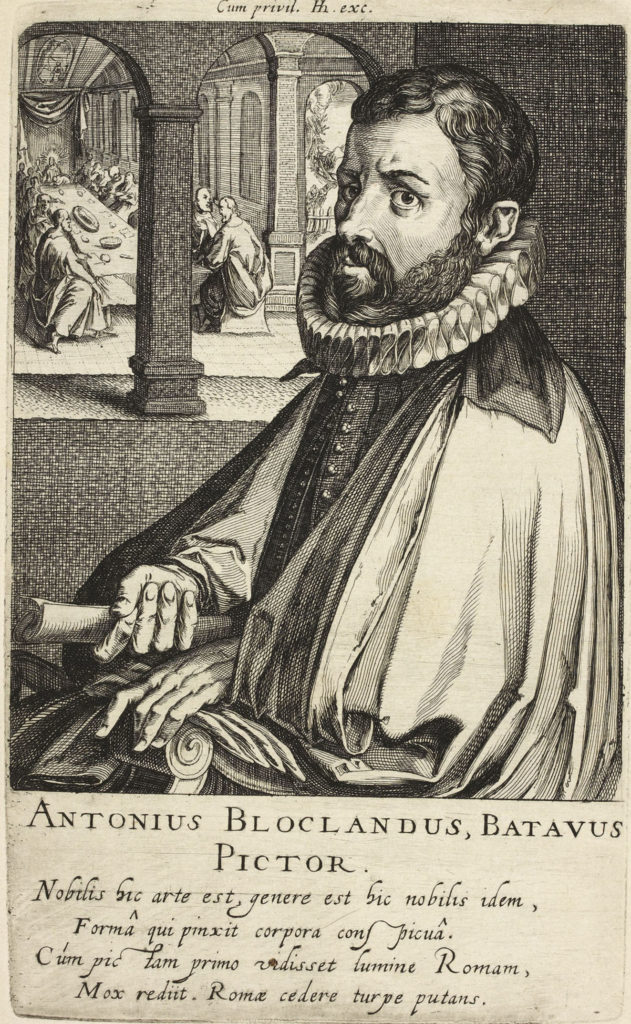

69. Anthonie Blocklandt

69. Anthonie Blocklandt

Etching

Signed 'Hh exc.' by Hendrick Hondius, attributed to Simon Frisius

20.3 x 12.4 cm

Transcription of Inscription:

ANTONIUS BLOCLANDUS, BATAVUS PICTOR.

Nobilis hic arte est, genere est hic nobilis idem,

Formâ qui pinxit corpora conspicuâ.

Cúm pictam primo vidisset lumine Romam,

Mox rediit Romae cedere turpe putans.

Translation of Inscription:

Anthonie Blocklandt the Dutchman, painter.

This man is noble in skill; this same man is noble by race. He painted bodies of remarkable shape.73 When he had seen Rome painted in the first light,74 he soon returned, thinking it disgraceful to yield to Rome.75

Orenstein 1996, Frisius no. 138; Hollstein 2008 no. 158

Karel Van Mander's biography of Anthonie Blocklandt

Grove Art Online biography

71. Frans Pourbus

71. Frans Pourbus

Engraved by Hendrick Hondius (Orenstein 1996)

Signed 'Hh form. Cum privil.' by Hendrick Hondius

19.8 x 12.2 cm

Transcription of Inscription:

FRANCISCUS POURBUSIUS, BRUGENSIS.

Patre fuit pictore satus Pourbusius : arte

Verum patre prior. Sic monumenta docent.

Vivunt, quas pinxit pecudes pictaéque volucres :

Pictoris lugent quae simul interitum.

Translation of Inscription:

Frans Pourbus of Bruges.

Pourbus was begotten by a painter father, but in skill he stood before his father. His monuments teach this. The flocks and coloured birds76 which he painted are alive, [and] they weep together for the painter’s death.

Hollstein 1994 no.106

Karel Van Mander's biography of Frans Pourbus

Grove Art Online biography

73. Hubert Goltzius

73. Hubert Goltzius

(After Philip Galle's engraving after Anthonis Mor.)

Engraving by Robert de Baudous (Orenstein 1996, 39)

Signed 'Hh exc.' by Hendrick Hondius

20.5 x 12.4 cm (irregular plate)

Transcription of Inscription:

HUBERTUS GOLTZIUS, VENLON. PICTOR

Ut gemma in nitido fulget praestantior auro

Chalcographus nitidus, clarus et Historicus:

Et Sculptor, Pictor : Romana Nomismata77, Fasti

Romanum civem quem voluere suum.

Translation of Inscription:

Hubert Goltzius of Venlo, painter

As a gem gleams more prominently in shining gold, [so] the shining bronze-engraver was also a famous historian, and a sculptor and painter, whom Roman coins and calendars wanted as their own Roman citizen.78

Orenstein 1996, Frisius no. 145; Hollstein 2008 no. 165

Karel Van Mander's biography of Hubert Goltzius

Grove Art Online biography

75. Dirck Barendsz

75. Dirck Barendsz

Engraved by Hendrick Hondius (Orenstein 1996)

Signed by 'Cum privil. Hh ex' by Hendrick Hondius

19.5 x 19.9 cm

Transcription of Inscription:

THEOD. BERNARDI, AMSTELDEN.

Vir gravis et doctus, pictor clarissimus idem,

Titiani magni prodiit ipse scholâ :

Usus et hic doctis, Algondo imprimis, et ipsa

Pictorum summo iudice Lampsonio.

Translation of Inscription:

Dirck Barendsz. of Amsterdam

A grave and learned man, also a most famous painter, he came himself from the school of great Titian.

Here too he had converse with the learned, especially Aldegonde,79 and the greatest judge of painters, Lampsonius himself.80

Hollstein 1994 no.107

Karel Van Mander's biography of Dirck Barendsz

Grove Art Online biography

77. Hans Bol

77. Hans Bol

Engraving by Andries Jacobsz. Stock (Orenstein 1996, 267)

Signed 'Hh form.' by Hendrick Hondius

20.7 x 12.1 cm

Transcription of Inscription:

IOANNES BOLLIUS, MECHLINIENSIS. PICTOR

Pictorum sedes dedit hunc Mechlinia Bollum,

Arte, nitore urbes quae superat reliquas.

Rura, lacus aqueo quamvis sint ducta colore ;

Non tamen haec abeunt more fluentis aquae.

Translation of Inscription:

Hans Bol of Mechelen, painter

The home of painters, Mechelen, which outdoes other cities in skill and splendour, gave this Bol.

Although fields and lakes are traced in watery colour, still they do not depart like flowing water.81

Orenstein 1996, Stock no. 267

Karel Van Mander's biography of Hans Bol

Grove Art Online biography

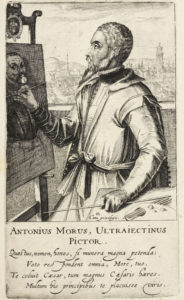

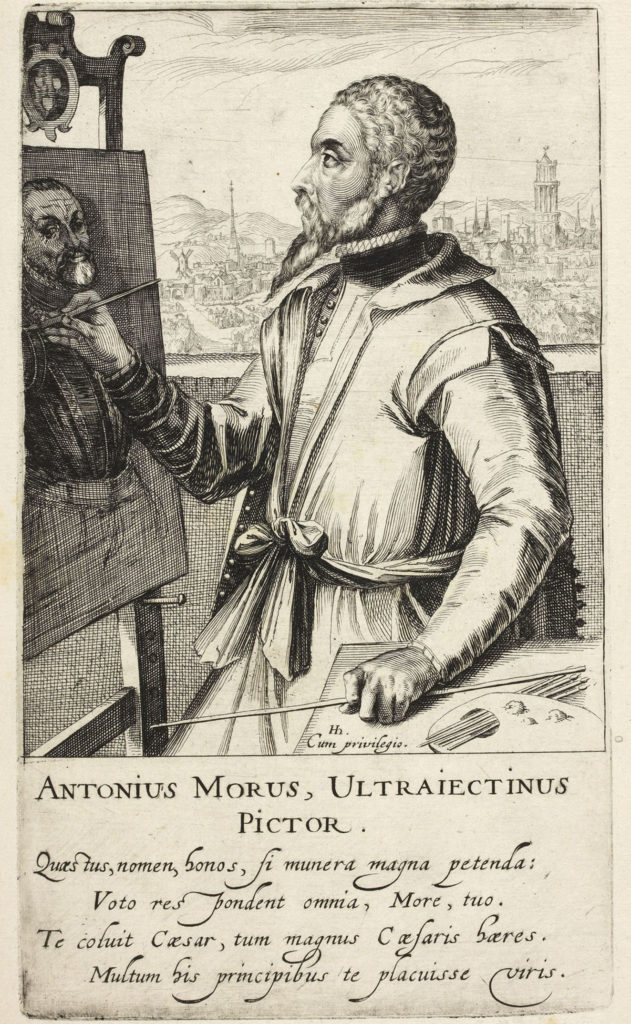

79. Anthonis Mor

79. Anthonis Mor

Etching

Signed 'Hh' by Hendrick Hondius, attributed to Simon Frisius

21 x 12.2 cm

Transcription of Inscription:

ANTONIUS MORUS, ULTRAIECTINUS PICTOR

Quaestus, nomen, honos, si munera magna petenda :

Voto respondent omnia, More, tuo.

Te coluit Caesar, tum magnus Caesaris haeres.

Multum his principibus te placuisse viris.

Translation of Inscription:

Anthonis Mor, Painter of Utrecht

Wealth, fame, honour (if great offices are to be sought) – everything answered to your wishes, Mor.82

The emperor honoured you, and the great successor of the emperor.83

It is much for you to have pleased these princely men.

Orenstein 1996, Frisius no. 151; Hollstein 2008 no. 171

Karel Van Mander's biography of Anthony Mor

Grove Art Online biography

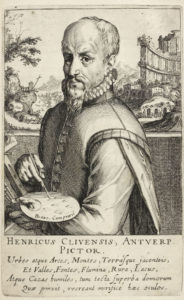

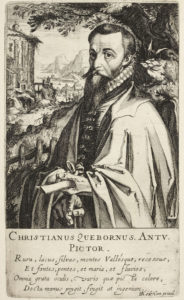

81. Hendrick van Cleef

81. Hendrick van Cleef

Etching and engraving

Signed 'Hh exc.' by Hendrick Hondius, attributed to Simon Frisius

19.5 x 12.2 cm

Transcription of Inscription:

HENRICUS CLIVENSIS, ANTVERP. PICTOR

Urbes atque Arces, Montes, Terrásque jacenteis84,

Et Valles, Fontes, Flumina, Rura, Lacus,

Atque Casas humiles, tum tecta superba domorum

Quae pinxit, recreant mirificé haec oculos.

Translation of Inscription:

Hendrick van Cleef of Antwerp. Painter

The cities and castles, mountains and low-lying lands, and valleys, fountains, rivers, fields, lakes and humble huts, besides the proud roofs85 of houses, which he painted – these wonderfully refresh the eyes.86

Orenstein 1996, Frisius no. 141; Hollstein 2008 no.161

Karel Van Mander's biography of Hendrick van Cleef

Grove Art Online biography

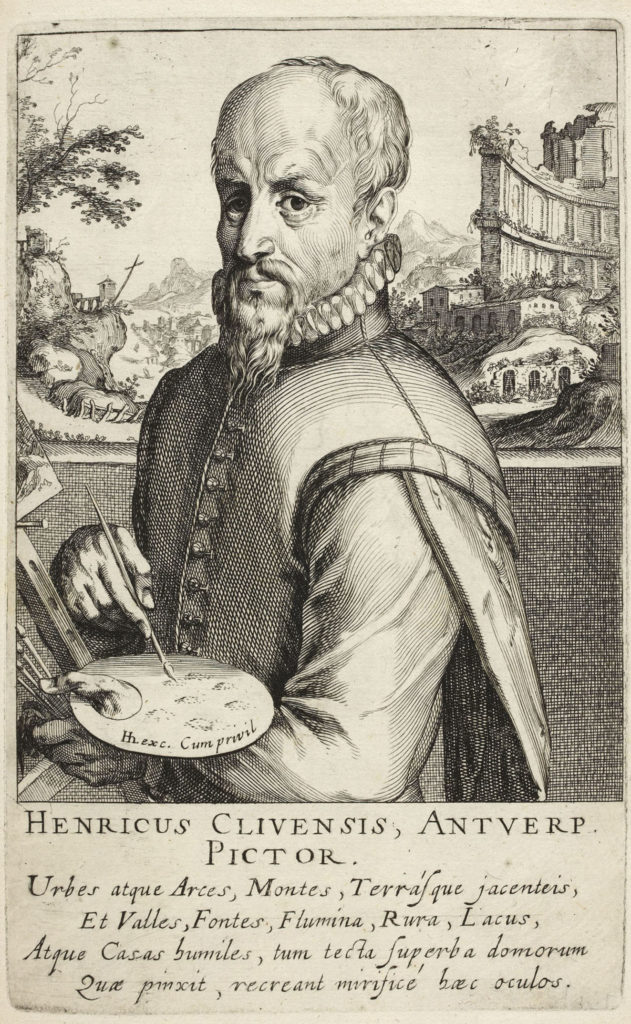

83. Christian van den Queborn

83. Christian van den Queborn

Etching

Signed 'Hh ex.' by Hendrick Hondius, attributed to Simon Frisius

20.1 x 11.6 cm

Transcription of Inscription:

CHRISTIANUS QUEBORNUS. ANTV. PICTOR.

Rura, lacus, silvas, montes Vallésque, recessus,

Et fontes, pontes, et maria, et fluvios,

Omnia grata oculis, vario quae picta colore,

Docta manus pingit, fingit at ingenium.

Translation of Inscription:

Christian van den Queborn of Antwerp, painter.

Fields, lakes, woods, mountains and valleys, caves, and fountains, bridges, and seas and rivers, all things pleasing to the eye, painted with varied colour – [these] his learned hand painted, but his mind imagined them.87

Orenstein 1996, Frisius no. 154; Hollstein 2008 no. 174

RKD artists biography

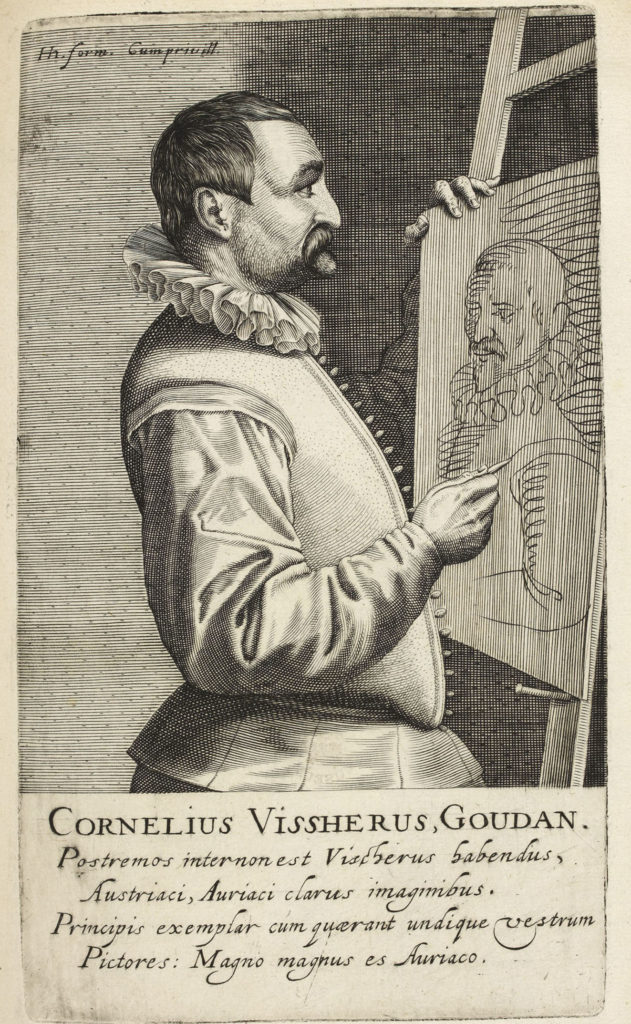

85. Cornelius Visscher

85. Cornelius Visscher

Engraving by Robert de Baudous (Orenstein 1996, 42)

Signed 'Hh form.' by Hendrick Hondius

20.6 x 12.2 cm

Transcription of Inscription:

CORNELIUS VISSHERUS, GOUDAN.

Postremos inter non est Vischerus habendus,

Austriaci, Auriaci clarus imaginibus.

Principis exemplar cum quaerant undique vestrum

Pictores : Magno magnus es Auriaco.

Translation of Inscription:

Cornelius Visscher of Gouda

Visscher, famous for images of the Hanoverian and the [Prince] of Orange, is not to be counted among the least. Since painters from everywhere seek your88 image of the prince, you are great by the great [Prince of] Orange.

Orenstein 1996, Baudous no. 42

Grove Art Online biography

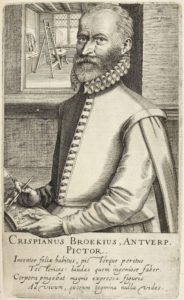

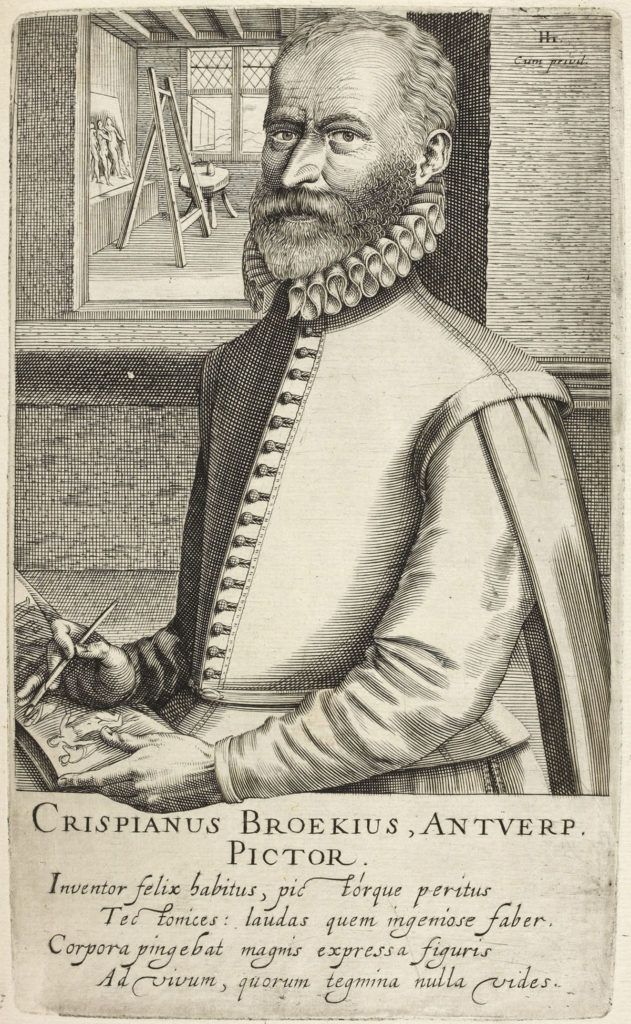

87. Crispijn van der Broeck

87. Crispijn van der Broeck

Engraved by Hendrick Hondius (Orenstein 1996)

Signed 'Hh Cum privil' by Hendrick Hondius

20.4 x 12.1 cm

Transcription of Inscription:

CRISPIANUS BROEKIUS, ANTVERP. PICTOR.

Inventor felix habitus, pictórque peritus

Tectonices : laudas quem ingeniose faber.

Corpora pingebat magnis expressa figuris

Ad vivum, quorum tegmina nulla vides

Translation of Inscription:

To Crispijn van den Broeck of Antwerp, painter

Ingenious craftsman,89 he whom you praise was thought to be a lucky inventor and a skilled painter of carpentry. He painted lifelike90 bodies set forth in large shapes. On these you shall see no covering.

Hollstein 1994 no.108

mentioned in Karel Van Mander’s life of Frans Floris

Grove Art Online biography

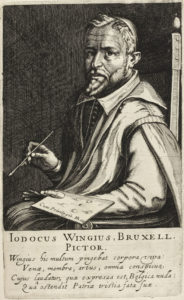

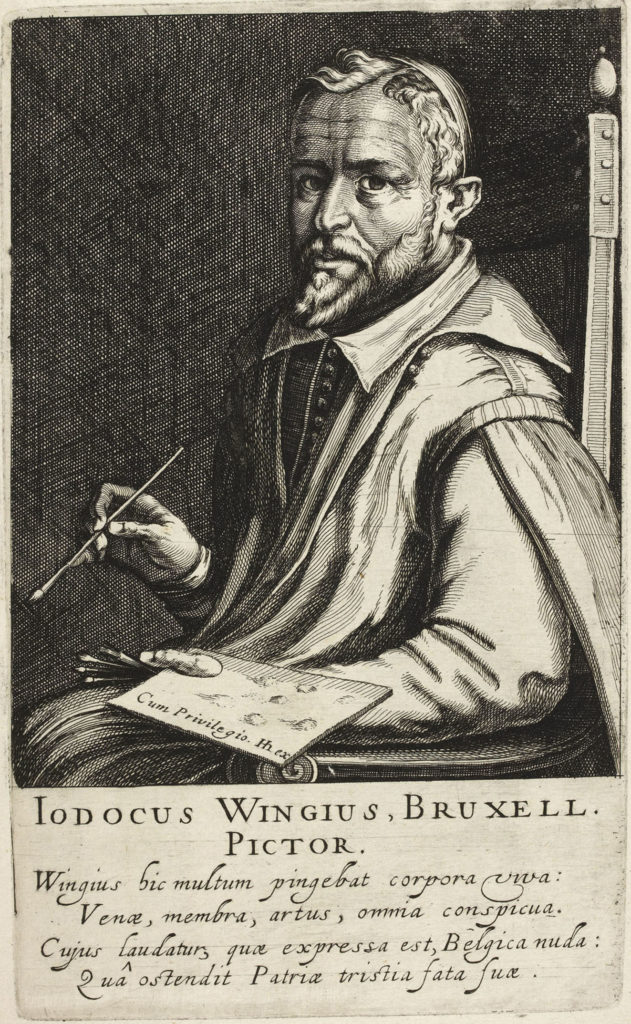

89. Joos van Winghe

89. Joos van Winghe

Etching

Signed 'Hh ex.' by Hendrick Hondius, attributed to Simon Frisius

20.1 x 11.9 cm

Transcription of Inscription:

IODOCUS WINGIUS, BRUXELL. PICTOR

Wingius hic multum pingebat corpora viva :

Venae, membra, artus, omnia consipicua.

Cujus laudatur, quae expressa est, Belgica nuda :

Quâ ostendit Patriae tristia fata suae.

Translation of Inscription:

Joos van Winghe of Brussels, painter

This van Winghe often painted living bodies – veins, limbs, joints, everything was remarkable. His Belgian nude, which has been printed,91 is praised. With her he showed the sad fate of his fatherland.

Orenstein 1996, Frisius no. 159; Hollstein 2008 no. 179

Karel Van Mander's biography of Joos van Winghe

Grove Art Online biography

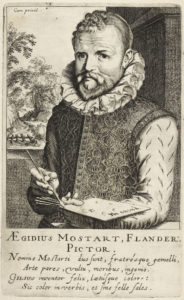

91. Gillis Mostaert

91. Gillis Mostaert

Etching and engraving

Signed 'Hh excud.' by Hendrick Hondius, attributed to Simon Frisius

20.3 x 12.5 cm

Transcription of Inscription:

ÆGIDIUS MOSTART, FLANDER. PICTOR.

Nomine Mostarti duo sunt, fratrésque gemelli,

Arte pares, vultu, moribus, ingenio.

Gilius inventor felix, laetúsque color92:

Sic color in verbis, et sine felle sales.

Translation of Inscription:

Gillis Mostaert of Flanders, painter

There are two twin brothers by the name of Mostaert. They are equal in skill, appearance, morals and genius.93 Gillis is a lucky inventor,94 rejoicing in colour. Thus there is colour95 in his words, and wit without bile.

Orenstein 1996, Frisius no. 152; Hollstein 2008 no.172

Karel Van Mander's biography of Gillis Mostaert

Grove Art Online biography

93. Joris Hoefnagel

93. Joris Hoefnagel

Etching

Signed 'Hh. formis' by Hendrick Hondius, attributed to Simon Frisius

21.2 x 12.5 cm

Transcription of Inscription:

GEORGIUS HOEFNAGLIUS PICT. ANTVERPIANUS

Doctrinâ excultus se offert Hoefnaglius ille,

Cosmographo docto fidus et Ortelio.

Hic Orbem, ille Urbes dedit Orbi ingente Theatro,

Et pinxit flores brutá96 que qui varia.

Translation of Inscription:

Joris Hoefnagel, painter of Antwerp

This Hoefnagel, refined by learning, presents himself. He was also trustworthy for the learned cosmographer Ortelius. The latter gave the world, [and] the former cities to the world in a gigantic Theatre,97 and painted flowers and various brute beasts.98

Orenstein 1996, Frisius no. 147; Hollstein 2008 no. 167

Karel Van Mander's biography of Joris Hoefnagel

Grove Art Online biography

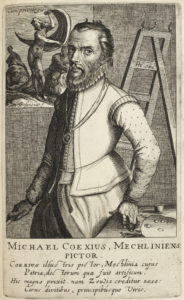

95. Michiel Coxcie

95. Michiel Coxcie

Etching and engraving

Signed 'Hh exc.' by Hendrick Hondius, attributed to Simon Frisius

20.4 x 12.4 cm

Transcription of Inscription:

MICHAEL COEXIUS, MECHLINIENS. PICTOR.

Coexius illustris pictor, Mechlinia cujus

Patria, doctorum quae fuit artificum.

Hic magno pinxit. nam Zeuxis creditur esse :

Carus divitibus, principibúsque Viris.

Translation of Inscription:

Michiel Coxie of Mechelen, painter

Coxie was an illustrious painter, whose fatherland was Mechelen, which was that of learned artists.99 He painted for a great price. For he was believed to be Zeuxis,100 [and] was dear to the rich and to princely men.

Orenstein 1996, Frisius no. 142; Hollstein 2008 no.162

Karel Van Mander's biography of Michiel Coxie

Grove Art Online biography

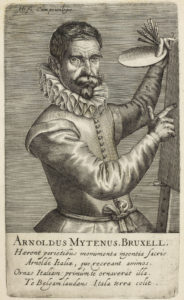

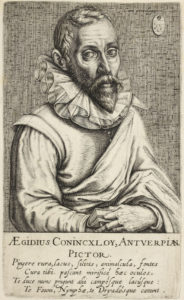

97. Arnold Mytens

97. Arnold Mytens

Engraved by Hendrick Hondius (Orenstein 1996)

Signed 'Hh f Cum privilegio' by Hendrick Hondius

20.1 x 11.8 cm

Transcription of Inscription:

ARNOLDUS MYTENUS. BRUXELL.

Haerent parietibus monumenta ingentia sacris

Arnolde Italiae, que101 recreant animos.

Ornas Italiam : primúm te ornaverat illa.

Te Belgam laudans Itala terra colit.

Translation of Inscription:

Arnold Mytens of Brussels

Arnold, gigantic monuments, which refresh souls,102 cleave to the sacred walls of Italy. You adorn Italy: first she adorned you. Praising Belgium, the land of Italy honours you.

Hollstein 1994 no.109

Karel Van Mander's biography of Arnold Mytens

RKD artists biography

99. Maarten de Vos

99. Maarten de Vos

Etching

Attributed to Simon Frisius

20.1 x 11.7 cm

Transcription of Inscription:

MARTINUS VOSSIUS, ANTVERPIAN. PICTOR.

Qui se offert oculis, Martinus Vossius ille :

Cujus erat frater pictor, et ipse pater.

Arte hic Martinus sane est Hemskerkius alter.

Nam simili ductu pinxit uterque, modo.

Translation of Inscription:

Maarten de Vos of Antwerp, painter

He who presents himself to [your] eyes is that Maarten de Vos, whose brother, and even father, were painters. In his skill this Maarten is surely a second Heemskerk. For both painted with a similar stroke [and]103 manner.

Orenstein 1996, Frisius no. 156; Hollstein 2008 no.176

Karel Van Mander's biography of Maarten de Vos

Grove Art Online biography

101. Hans Vredeman de Vries

101. Hans Vredeman de Vries

101Engraved by Hendrick Hondius (Orenstein 1996)

Signed 'Hh form. Cum privil.' by Hendrick Hondius

19.8 x 11.6 cm

Transcription of Inscription:

IOANNES VREDEMANNUS FRISIUS. LEOVARDIENSIS.

Pictorum summus, celebrat quos Optica virtus,

Friso : probant artem Regia tecta tuam.

Cum tua sint Opera haec varii104 subnixa Columnis

Spectabit longo tempore posteritas.

Translation of Inscription:

Hans Vredeman de Vries of Leeuwarden

Frisian, greatest of painters whom skill in optics makes famous, the royal palace proves your skill. Since these works are yours, supported by diverse105 columns, posterity shall gaze upon them for a long time.

Hollstein 1994 no.110

Karel Van Mander's biography of Hans Vredeman de Vrie

Grove Art Online biography

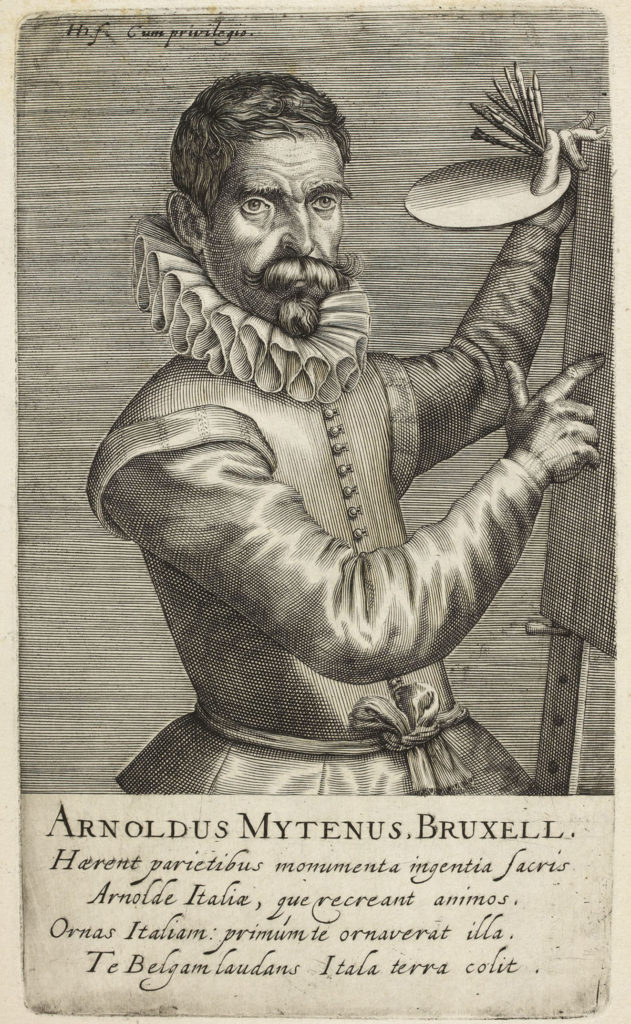

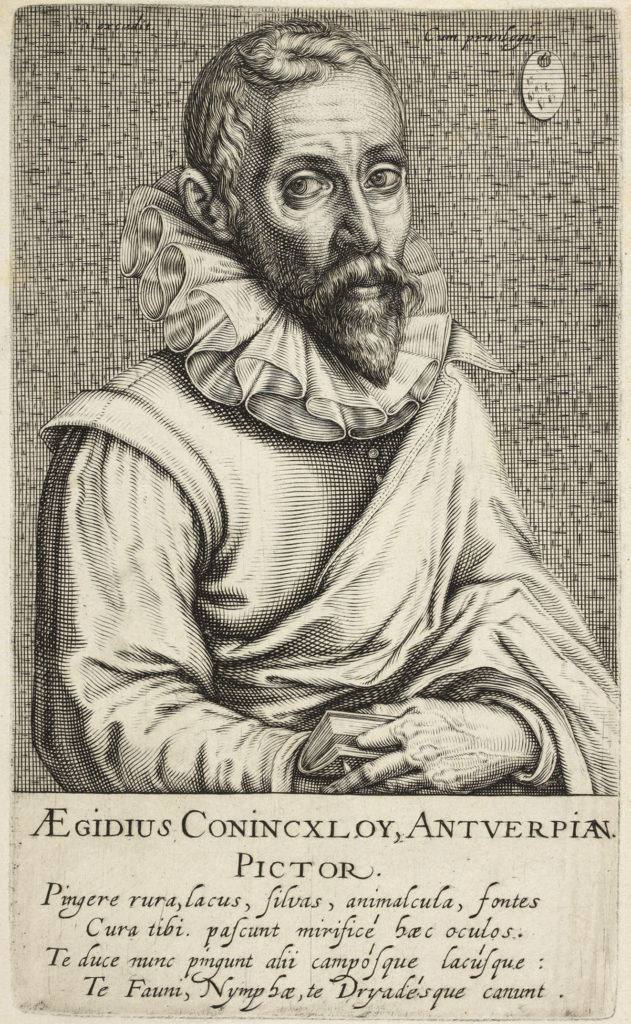

103. Gillis Coninxloo

103. Gillis Coninxloo

Engraving by Andries Jacobsz. Stock (Orensrtein 1996, 268)

Signed 'Hh excudit' by Hendrick Hondius

202 x 12.1 cm

Transcription of Inscription:

ÆGIDIUS CONINCXLOY, ANTVERPIAN. PICTOR.

Pingere rura, lacus, silvas, animalcula, fontes

Cura tibi. pascunt mirificé haec oculos.

Te duce nunc pingunt alii campósque lacúsque :

Te Fauni, Nymphae, te Dryadésque canunt.

Translation of Inscription:

Gillis Coninxloo of Antwerp, painter

Your concern was to paint fields, lakes, small animals and fountains. These things nourish 106 the eyes wonderfully. By your example, now others paint fields and lakes: the Fauns, the Nymphs and the Dryads sing of you.

Orenstein 1996, Stock no. 268

Karel Van Mander's biography of Gillis Coninxloo

Grove Art Online biography

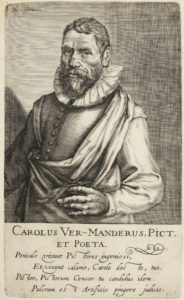

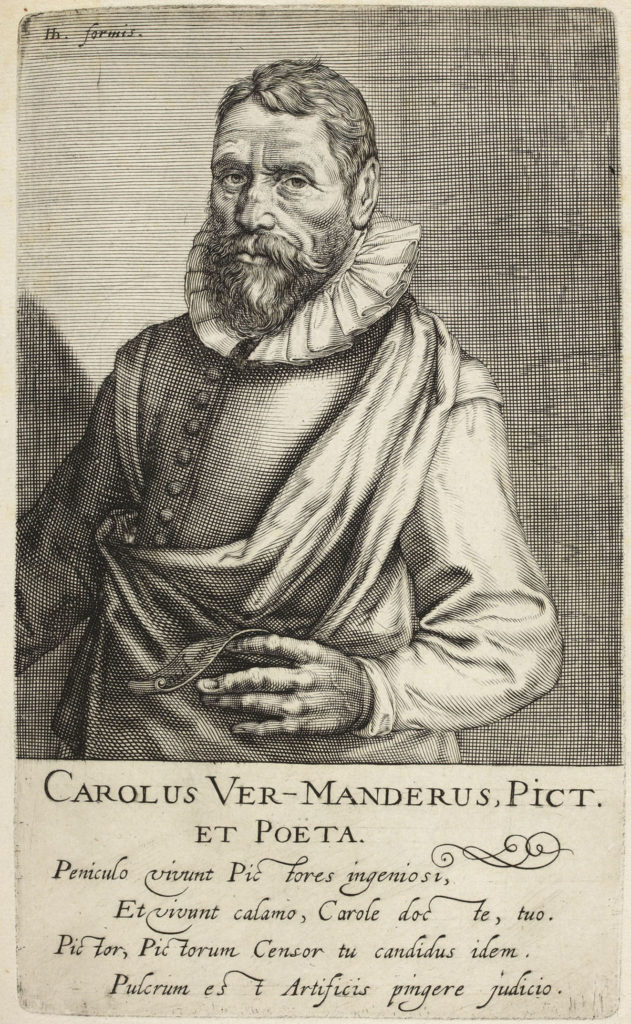

105. Karel van Mander

105. Karel van Mander

Engraving by Andries Jacobsz. Stock (Orenstein 1996, 269)

Signed 'Hh. formis' by Hendrick Hondius

20.4 x 12.2 cm

Transcription of Inscription:

CAROLUS VER-MANDERUS, PICT. ET POETA.

Peniculo vivunt Pictores ingeniosi,

Et vivunt calamo, Carole docte, tuo.

Pictor, Pictorum Censor tu candidus idem.

Pulcrum est Artificis pingere judicio.

Translation of Inscription:

Karel van Mander, Painter and Poet

Ingenious pictures live by their brush, and they live, learned Karel, by your pen. You are at the same time a painter and the candid censor of painters.107. It is a fine thing to paint for the judgment of an artist.

Orenstein 1996, Stock no. 269

Karel Van Mander's Het Schilder-boeck

Grove Art Online biography

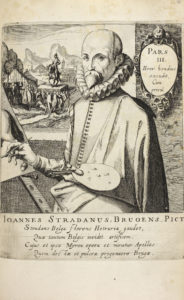

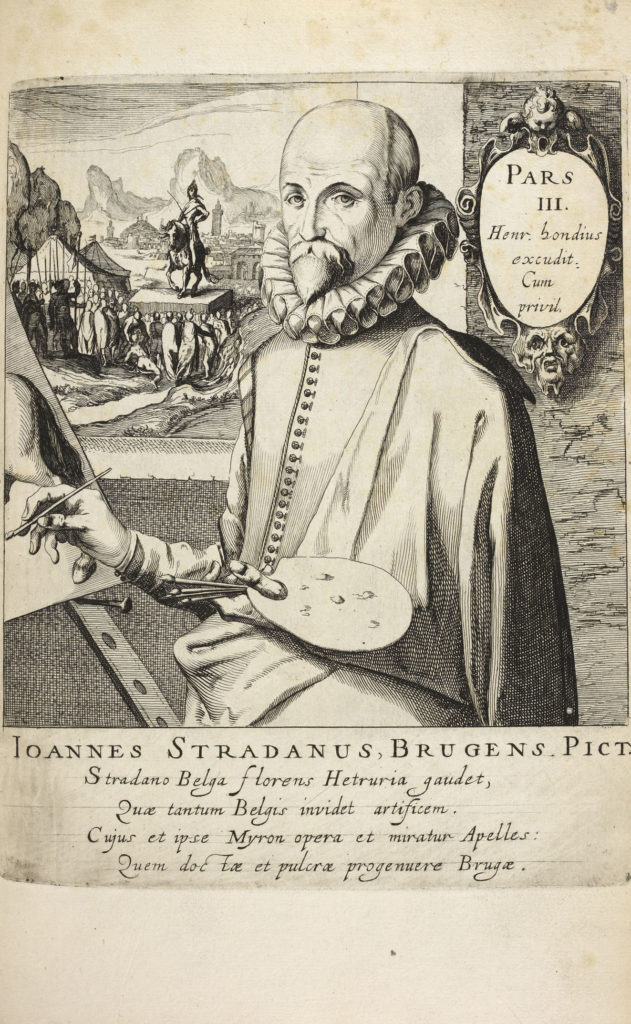

107. Johannes Stradanus

107. Johannes Stradanus

Etching, second state

Inscribed on cartouche 'Pars III. Henr. hondius excudit. Cum Privil.', attributed to Simon Frisius

19.9 x 15.9 cm

Transcription of Inscription:

IOANNES STRADANUS, BRUGENS. PICT.

Stradano Belga florens Hetruria gaudet,

Quae tantum Belgis invidet artificem.

Cujus et ipse Myron opera et miratur Apelles :

Quem doctae et pulcrae progenuere Brugae.

Translation of Inscription:

Johannes Stradanus, painter of Bruges

Flowering Tuscany rejoices in the Belgian van der Straet. She envies the Belgians so great an artist, whose works Myron himself and Apelles admire, whom beautiful, learned Bruges brought forth.

Orenstein 1996, Frisius no. 155; Hollstein 2008 no.175

Karel Van Mander's biography of Johannes Stradanus

Grove Art Online biography 107

111. Cornelius Ketel

111. Cornelius Ketel

Engraved by Hendrick Hondius (Orenstein 1996)

Signed 'Hh. Esc. Cum privil.' by Hendrick Hondius

20.9 x 11.8 cm

Transcription of Inscription:

CORNELIUS KETEL, GOUDANUS.

Primus hic á Luca Leidano pictor habetur

Goudanus, Batavi gloria uterque soli.

Quam bene conveniant, docuit, Pictura, Poesis :

Quae pinxit, prius hic finxerat ingenio.

Translation of Inscription:

Cornelius Ketel of Gouda.

This man of Gouda is held to be the greatest painter after Lucas van Leyden – both [are] glories of the Dutch land. He taught how well painting and poetry108 go together. What he painted, the other109 had first imagined110 with his genius.

Hollstein 1994 no.111

Karel Van Mander's biography of Cornelius Ketel

Grove Art Online biography

113. Hans von Aachen

113. Hans von Aachen

Engraving by Andries Jacobsz. Stock (Orenstein 1996, 270)

Signed 'Hh exc.' by Hendrick Hondius

20.4 x 12.3 cm

Transcription of Inscription:

IOANNES AQUANUS, COLONIENSIS. PICTOR.

Picturae Aquanus primus111 se tradit ab annis :

Quae praestat juvenis vix potuere viri.

Germanum juvenem cúrri temneret Itala tellus ;

Mox artem observans Roma magistra stupet.

Translation of Inscription:

Hans von Aachen

Aachen gave himself over to painting from his earliest years.112 What the youth accomplished men could scarcely do. Although the Italian land despised the German youth, soon, observing his skill, mistress Rome was amazed.

Orenstein 1996, Stock no. 270

RKD artists biography

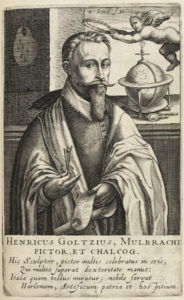

115. Hendrick Goltzius

115. Hendrick Goltzius

Etching

Signed 'Hh ex' by Hendrick Hondius, attributed to Robert de Baudous

20 x 12.5 cm

Transcription of Inscription:

HENRICUS GOLTZIUS, MULBRACHT. PICTOR, ET CHALCOG.

Hic Sculptor, pictor multis celebratus in oris,

Qui multos superat dexteritate manus:

Itala quem tellus miratur ; nobile servat

Harlemum, Artificum patria et hospitium.

Translation of Inscription:

Hendrick Goltzius of Mülbracht, painter and bronze-engraver

This is the sculptor and painter celebrated in many lands, who surpassed many in the dexterity of his hand, [and] whom the land of Italy admired. He remains in noble Haarlem, fatherland and guesthouse of artists.

Orenstein 1996, Baudous no. 39

Karel Van Mander's biography of Hendrick Goltzius

Grove Art Online biography

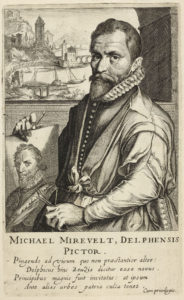

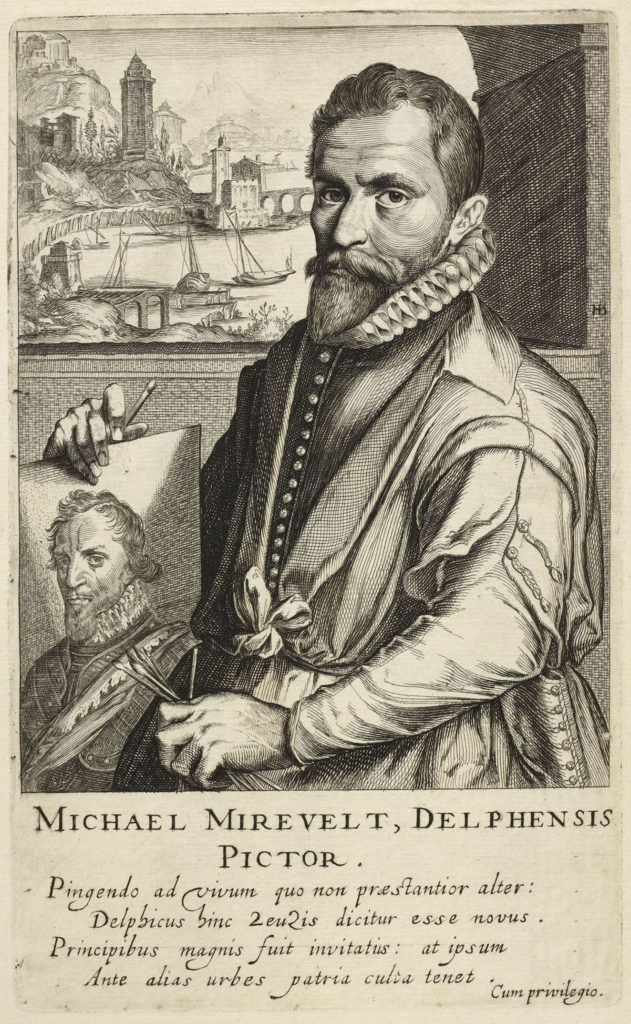

119. Michael van Mierevelt

119. Michael van Mierevelt

Etching and engraving

Signed 'Hh' by Hendrick Hondius, attributed to Simon Frisius

20.2 x 12.4 cm

Transcription of Inscription:

MICHAEL MIREVELT, DELPHENSIS PICTOR. 119

Pingendo ad vivum quo non praestantior alter :

Delphicus hinc Zeuxis dicitur esse novus.

Principibus magnis fuit invitatus: at ipsum

Ante alias urbes patria culta tenet.

Translation of Inscription:

Michael van Mierevelt of Delft, painter

No one was more eminent in painting in lifelike manner.113Therefore the man of Delft was said to be the new Zeuxis.114 He was invited by great princes: but his honored fatherland held him more than other cities.

Orenstein 1996, Frisius no. 149; Hollstein 2008 no.169

Karel Van Mander's biography of Michael van Mierevelt

Grove Art Online biography

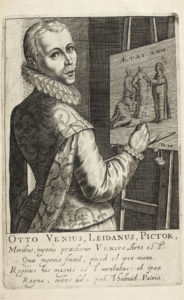

121. Otto van Veen

121. Otto van Veen

Engraving by Robert de Baudous (Orenstein 1996, 41)

Signed 'Hh ex.' by Hendrick Hondius

19.2 x 12.7 cm

Transcription of Inscription:

OTTO VENIUS, LEIDANUS, PICTOR,

Moribus, ingenio praeclarus Venius Arte est.

Quae ingenio finxit, pinxit et ipse manu.

Regibus hic magnis est invitatus : at ipse

Regna, orbes dulci posthabuit Patria.

Translation of Inscription:

Otto van Veen of Leyden, painter,

Van Veen is illustrious for his morals, his genius and his skill.115 What his genius imagined, he also painted with his own hand. He was invited by great kings, but he himself held kingdoms and worlds to be less important than his sweet fatherland.

Orenstein 1996, Baudous no. 41

Karel Van Mander's biography of Otto van Veen

Grove Art Online biography

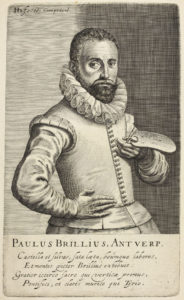

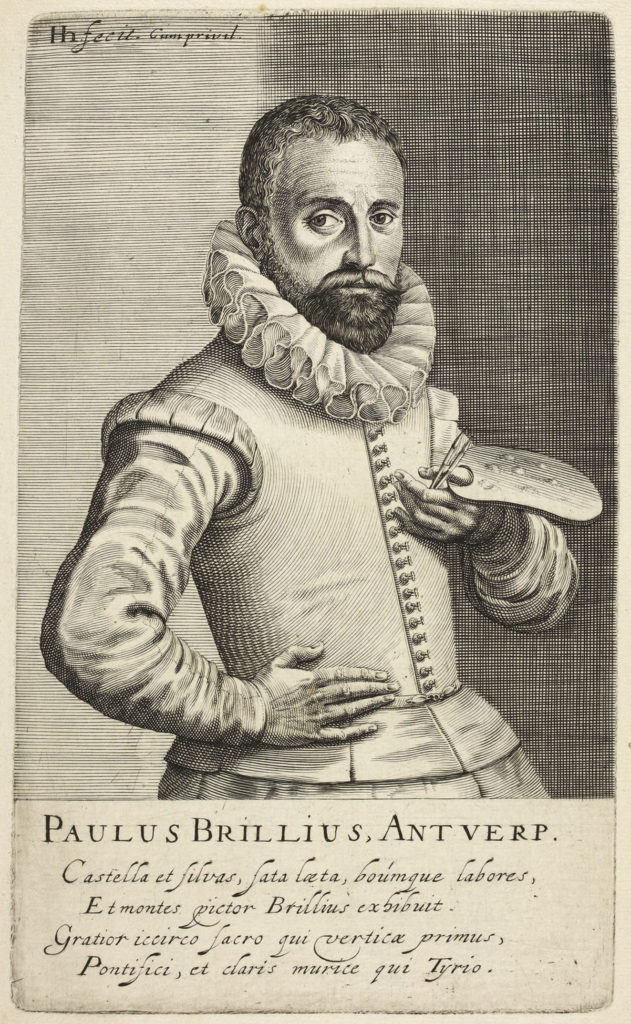

123. Paul Bril

123. Paul Bril

Engraved by Hendrick Hondius (Orenstein 1996)

Signed 'Hh fecit. Cum privil.' by Hendrick Hondius

20.7 x 12.3 cm

Transcription of Inscription:

PAULUS BRILLIUS, ANTVERP.

Castella et silvas, sata laeta, boúmque labores,

Et montes pictor Brillius exhibuit.

Gratior iccirco sacro qui verticae. 117murice qui Tyrio.

Translation of Inscription:

Paul Bril of Antwerp

Brill the painter showed fortresses and woods, joyous crops and the work of oxen, 118 and mountains. Therefore he was the more pleasing to the one who is first on the holy summit (the Pontiff), and to the one who is illustrious 119 in Tyrian purple. 120

Hollstein 1994 no.113

Karel Van Mander's biography of Paul Bril

Grove Art Online biography

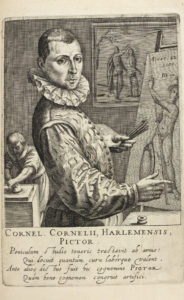

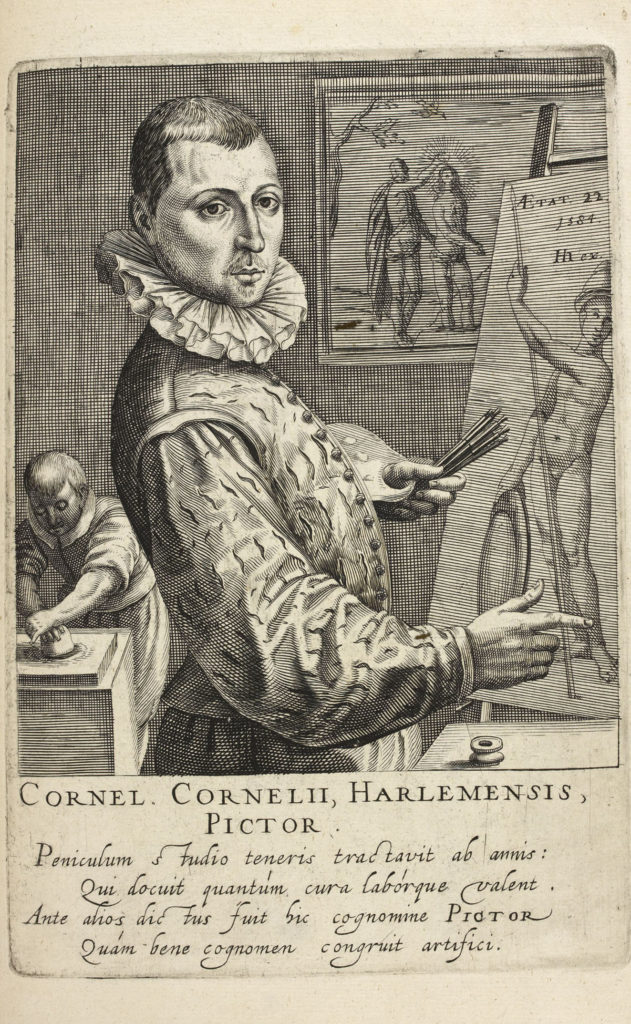

125. Cornelius Cz. van Haarlem

125. Cornelius Cz. van Haarlem

Engraving by Robert de Baudous (Orenstein 1996, 38)

Signed 'Hh ex.' by Hendrick Hondius

Transcription of Inscription:

CORNEL. CORNELII, HARLEMENSIS, PICTOR.

Peniculum studio teneris tractavit ab annis :

Qui docuit quantúm cura labórque valent.

Ante alios dictus fuit hic cognomine PICTOR

Quám bene cognomen congruit artifici.

Translation of Inscription:

Cornelis Cornelisz. van Haarlem, painter

He used the paintbrush with zeal from his tender years, he who taught how much taking pains and working hard can accomplish. Before others he was known by the nickname “painter”. How well the nickname matches the artist!

Orenstein 1996, Baudous no. 38

Karel Van Mander's biography of Cornelis Cornelisz. van Haarlem

Grove Art Online biography

127. Jacques de Gheyn II

127. Jacques de Gheyn II

Engraving by Andries Jacobsz. Stock (Orenstein 1996, 271)

Signed 'Hhondius exc.' by Hendrick Hondius

20.3 x 12.4 cm

Transcription of Inscription:

IACOBUS DE GEYN, ANTVERP, PICT ET SCULPT.

Geinius eximius Scalptor, Pictórque peritus,

Inventor felix, judicióque bonus.

Et Belli et Pacis pingens Insignia, gratus

Ipse Duci Belli qui artibus egregius.

Translation of Inscription:

Jacques de Gheyn. Painter and Sculptor

De Gheyn is an excellent engraver, and an experienced painter, a lucky inventor,121 Gillis Mostaert.and sound in judgment. Painting the standards of both war and peace, he is himself pleasing to the leader of the war, who is outstanding in skill. 122

Orenstein 1996, Stock no. 271

Karel Van Mander's biography of Jacques de Gheyn

Grove Art Online biography

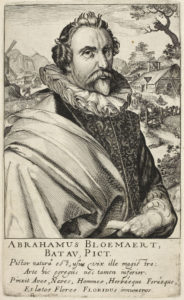

129 Abraham Bloemaert

129 Abraham Bloemaert

Etching and engraving

Attributed to Simon Frisius

20.3 x 12.2 cm

Transcription of Inscription:

ABRAHAMUS BLOEMAERT, BATAV, PICT.

Pictor naturâ est, usus vix ille magistro :

Arte hic egregiis nec tamen inferior.

Pinxit Aves, Naves, Homines, Herbásque Ferásque,

Et laetos Flores FLORIDUS innumeros.

Translation of Inscription:

Abraham Bloemaert the Dutchman, Painter

He was a painter by nature: having hardly used a master, he123was yet not inferior to those outstanding in skill. He painted birds, ships, men, and grass and wild beasts, and, being Florid,124 countless joyful flowers.

Orenstein 1996, Frisius no. 139; Hollstein 2008 no.159

Karel Van Mander's biography of Abraham Bloemaert

Grove Art Online biography

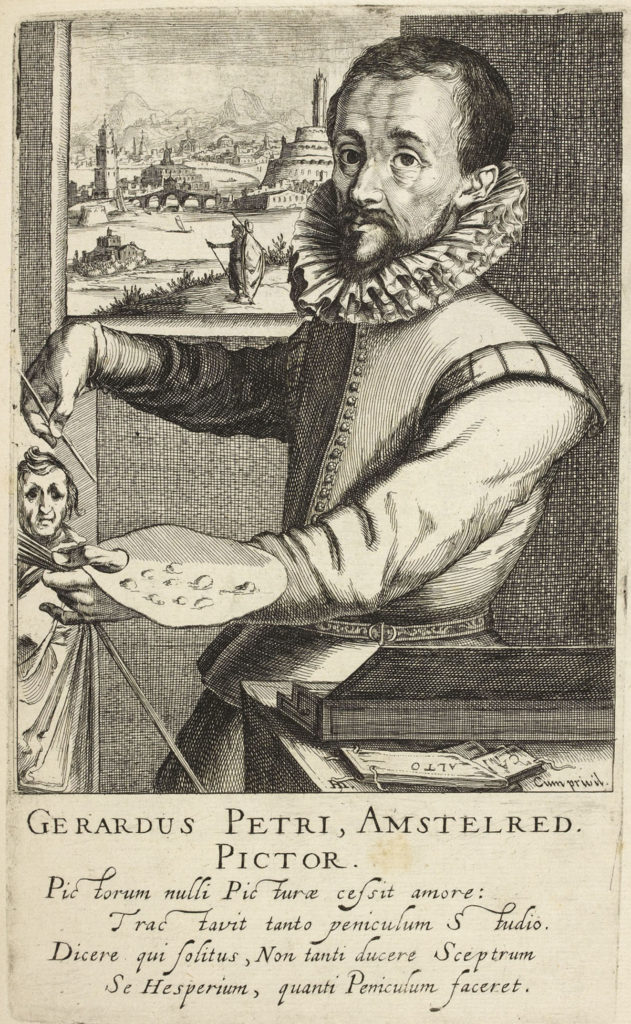

131. Gerrit Pietersz

131. Gerrit Pietersz

Etching

Signed 'Hh.' by Hendrick Hondius, attributed to Simon Frisius

20.1 x 12 cm

Transcription of Inscription:

GERARDUS PETRI, AMSTELRED. PICTOR.

Pictorum nulli Picturae cessit amore :

Tractavit tanto peniculum Studio.

Dicere qui solitus, Non tanti ducere Sceptrum

Se Hesperium, quanti Peniculum faceret.

Translation of Inscription:

Gerard Pietersz. of Amsterdam, painter 131

He yielded to no painter in his love of painting, with such great zeal did he use the paintbrush, he who was accustomed to say that he did not value the Hesperian sceptre125 as much as the paintbrush.

Orenstein 1996, Frisius no. 153; Hollstein 2008 no.173

mentioned in Karel Van Mander’s life of Cornelis Cornelisz. Van Haarlem

Grove Art Online biography

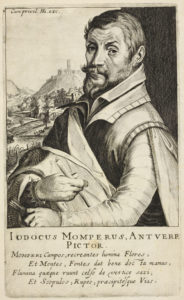

133. Joos de Momper

133. Joos de Momper

Etching and engraving

Signed 'Hh exc.' by Hendrick Hondius, attributed to Simon Frisius

20.6 x 12.2 cm

Transcription of Inscription:

IODOCUS MOMPERUS, ANTVERP. PICTOR.

Momperi Campos, recreantes lumina Flores,

Et Montes, Fontes data bene docta manus,

Flumina quaéque ruunt celso de vertice saxi,

Et scopulos, Rupes, praecipitésque Vias.

Translation of Inscription:

Joos de Momper of Antwerp, painter.

The well-taught hand of Momper offers fields, flowers that refresh the eyes,126 and mountains [and] fountains, also rivers which rush from the high peak of a stone, and cliffs, rocks, and headlong paths.

Orenstein 1996, Frisius no. 150; Hollstein 2008 no.170

Grove Art Online biography

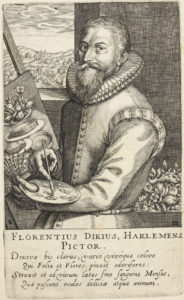

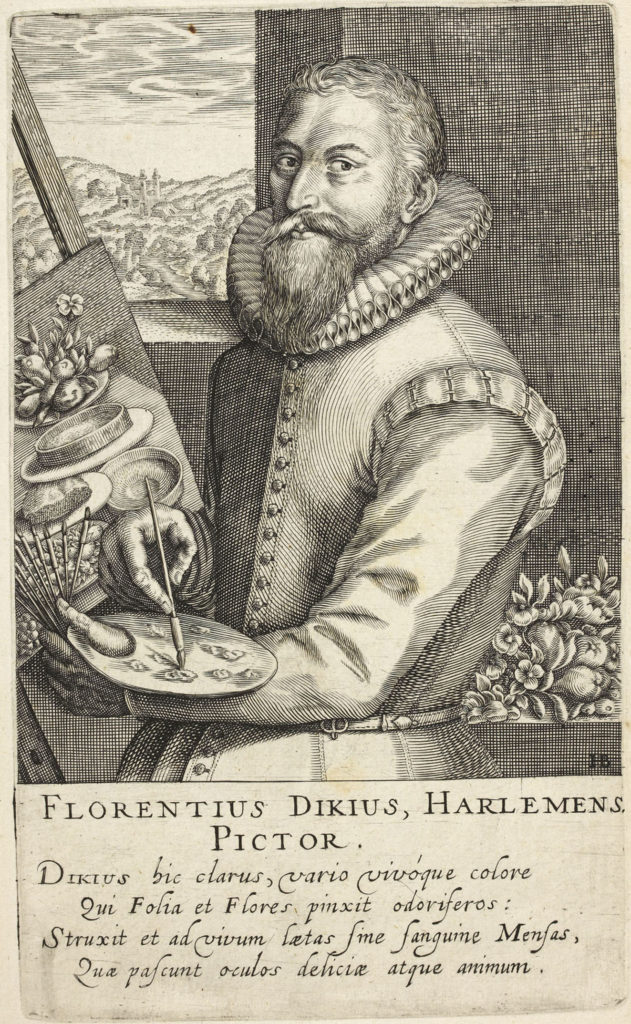

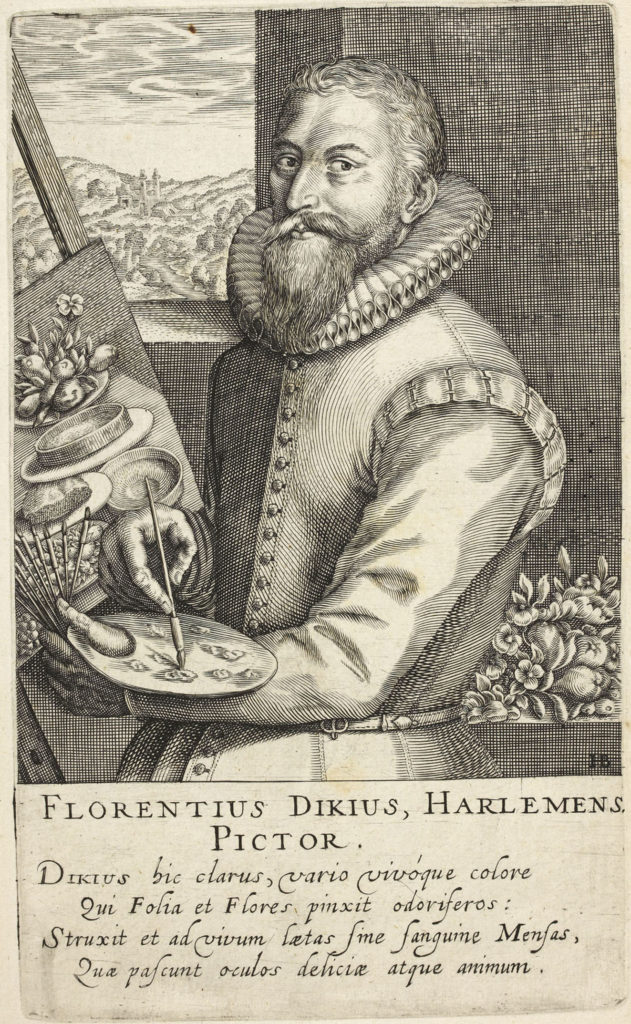

135. Floris van Dijck

135. Floris van Dijck

Engraved by Hendrick Hondius (Orenstein 1996)

20.6 x 12.4 cm

Transcription of Inscription:

FLORENTIUS DIKIUS, HARLEMENS. PICTOR.

Dikius hic clarus, vario vivóque colore

Qui Folia et Flores pinxit odoriferos :

Struxit et ad vivum laetas sine sanguine Mensas,

Quae pascunt oculos deliciae atque animum.

Translation of Inscription:

Floris van Dijck, Painter of Haarlem

Here is van Dijck, famous for his varied and lively colour, he who painted leaves and fragrant flowers. He also set up lifelike joyous tables without blood. These delights nourish the eyes 127.and the mind.

Hollstein 1994 no.114

Grove Art Online biography

137. Adriaen De Vries

137. Adriaen De Vries

Etching and engraving

Signed 'Hh.' by Hendrick Hondius, attributed to Simon Frisius128

20.3 x 12.1 cm

Transcription of Inscription:

ADRIANUS DE VRIES, HAGIENSIS. PICTOR.

Friso bonus Pictor, Pario quoque marmore finxit

Qui Statuas : credas esse Myronis opus.

Et clarus scalptor Mullerus sit tibi testis,

Hunc qui miratur tum colit artificem.

Translation of Inscription:

Adriaen de Vries of The Hague, painter

The Frisian was a good painter, who also made statues from Parian marble: you would believe [them] to be the work of Myron. Let the famous engraver Muller also be a witness for you, he who admired and then frequented this artist.

Orenstein 1996, Frisius no. 157; Hollstein 2008 no.177

Grove Art Online biography

139. Frans Badens

139. Frans Badens

Engraving by Robert de Baudous (Orenstein 1996, 37)

Signed 'Hh excud.' by Hendrick Hondius

20.3 x 12.5 cm

Transcription of Inscription:

FRANCISCUS BADENSIS, ANTVERP. PICTOR.

Addit picturae meliús nemo colores :

Qui verus color est noscis imaginibus

Tu pictor doctus. multum est novisse colores.

Delitias doctas pingis et Italiae.

Translation of Inscription:

Frans Badens of Antwerp, painter.

No one was better at adding colours to a painting. You know which is the right colour for images.129 You are a learned painter. It is much to know colours. You also paint the learned delights of Italy.

Orenstein 1996, Baudous no. 37

Karel Van Mander's biography of Frans Badens

RKD artists biography

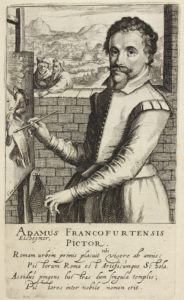

141. Adam Elsheimer

141. Adam Elsheimer

Etching

Signed 'Hh' by Hendrick Hondius, attributed to Simon Frisius

20.9 x 12.3 cm

Transcription of Inscription:

ADAMUS ELSHEYMER, FRANCOFURTENSIS PICTOR.

Romam urbem primis placuit tibi 130 visere ab annis :

Pictorum Roma est Artificúmque Schola.

Assiduó pingens lustras dum singula templis ;

Pictores inter nobile nomen erit.

Translation of Inscription:

Adam Elsheimer, painter of Frankfurt

It pleased you to visit Rome from your earliest years. Rome is the school of painters and artists. You were busy painting while examining every single thing in the churches.2 131 Among painters your name will be noble.

Orenstein 1996, Frisius no. 144; Hollstein 2008 no.164

mentioned in Van Mander’s biography of Hans Rottenhammer

Grove Art Online biography

143. Isaac Oliver

143. Isaac Oliver

Engraving by Robert de Baudous (Orenstein 1996, 40)

Signed 'Hh exv.' by Hendrick Hondius

20.6 x 11.9 cm

Transcription of Inscription:

ISAACUS OLIVERUS, ANGLUS, PICTOR.

Ad vivum laetos qui pingis imagine vultus,

Olivere oculos mirificé hi capiunt

Corpora quae formas justo haec expressa Colore.

Multum est, cúm rebus convenit ipse color.

Translation of Inscription:

Isaac Oliver the Englishman, painter.

You who paint images of lively,132 joyful faces, Oliver - these captivate (our) eyes wonderfully. The bodies which you make - these are expressed in the right colours.

It is a great thing, when colour itself is in harmony with things.

Orenstein 1996, Baudous no. 40

Grove Art Online biography

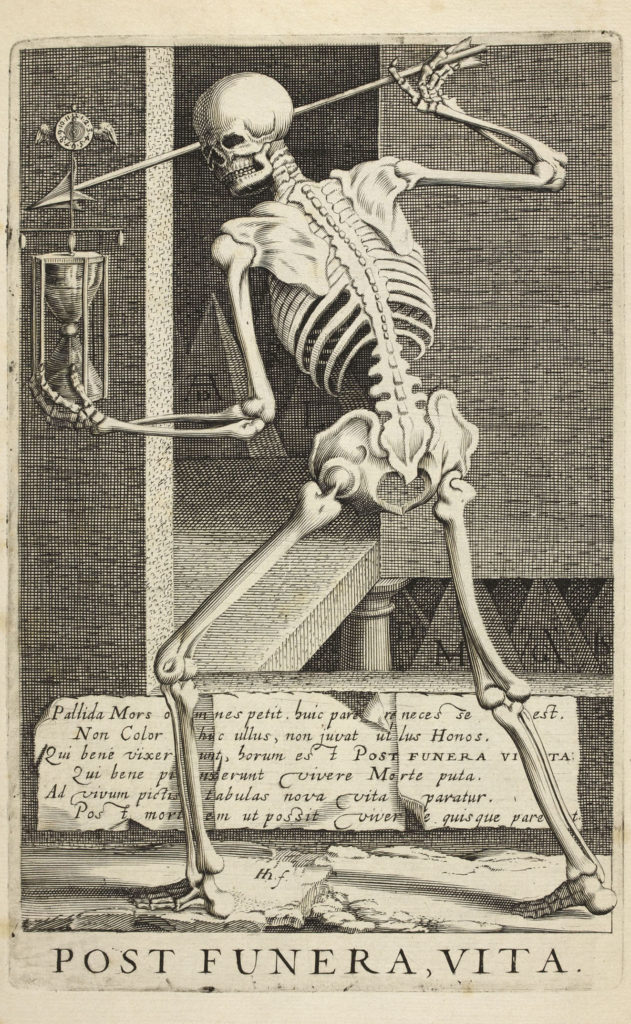

145. Post Funera Vita: After Burial, Life

145. Post Funera Vita: After Burial, Life

Engraved by Hendrick Hondius (Orenstein 1996)

Signed Hh.f. by Hendrick Hondius

21.5 x 13.7 cm

Monograms of deceased artists on pyramids: AD [Albrecht Dürer]; L [Lucas van Leyden]; D [?]; MVH [Maarten van Heemskerk]; AG [Heinrich Aldegrever]; HS [Hans Schäufelein]

On the fictive paper:

Transcription:

POST FUNERA VITA

Pallida Mors omnes petit. huic parere necesse est.

Non Color hic ullus, non juvat ullus Honos.

Qui bene vixerunt, horum est POST FUNERA VITA :

Qui bene pinxerunt vivere Morte puta.

Ad vivum pictis tabulas nova vita paratur.

Post mortem ut possit vivere quisque parent.

Translation:

Pale death133 attacks all. We have to obey it. No colour or honour is of any help here. For those who have lived well, there is life after burial. [As for] those who have painted well, consider that they live in death. A new life is set out in lifelike paintings134: let each set out to be able to live after death.

Footnotes:

- “Fructus” can be singular or plural.

- Nadine Orenstein comp., Huigen Leeflang ed., The New Hollstein. Dutch and Flemish Etchings, Engravings and Woodcuts 1450-1700, Simon Frisius 2 vols, Ouderkerk aan den Ijssel, 2008.

- “quod variumque novum: “literally the solecism “what is and various new pleases”. Cf. also note on Joachim Beuckelaer: “tabulasque culinas”.

- The most probable sense of “imaginibus” here is perhaps “portraits”.

- “Almost all these are those...”. One could also translate “these are almost all the ones...”

- “ingenio cedere turpe putat”. Cf. Anthonie Blocklandt: “Romae cedere turpe putans”.

- "pictorum censor" - the same expression at Karel van Mander, and the very similar "artis censori" at Jacob Binck, apparently of the author.

- One of the muses. Cf. The poem on Lucas van Leyden, “nostrae ...Camenae”.

- “ope” could also mean “wealth”. Either way, it’s hard to see (without knowing the context) how Hubert will feel this adds to his praises.

- This for “vestrum”, which is plural, so the work is being credited to both brothers.

- “amore sui” could also mean “love of himself”, but I am presuming that the author is referring to the Lam Gods.

- “ille ego qui” – For the ultimate source of this phrase, see the apocryphal opening lines to the Aeneid, “ille ego qui quondam gracili modulatus avena…”

- “oleo de semine lini”: the same expression in the poem for Cornelis Engebrechtsz.

- This for “probitas”. It is hard to see quite what the author means, but “probitas” to my knowledge always has a moral sense.

- I am taking “rerum genetrice” as qualifying “arte” in the next line. This is awkward, but I cannot see a better solution.

- The entry to the underworld in Virgil’s Aeneid.

- The sense seems to be that Rogier painted as well as he could for his time. Compare to poem on Jan Gossaert

- The point seems to be that Rogier’s paintings will pass away, like all earthly things, whereas his works of mercy will gain him eternal life, and therefore last forever.

- I translate as if “doctissima” agrees with “Bernardus”. This is in fact impossible, as “doctissima” is feminine. It could agree with “aulica … Bruxella”, or be a vocative, addressing Margaret. But neither of these options makes much sense. Nor can it be corrected to “doctissimus” without spoiling the metre.

- The reference, which is found in classical poetry, is to Attalus III of Pergamum, credited with the invention of cloth of gold.

- "me iudice certet". Cf. Virgil, Eclogue 4, 58, "mecum si iudice certet".

- Cornelis Cort (c.1533-1578)

- “rura ... et casas”. The combination (also found in Lucas Gassel below) is from Virgil, Eclogues 2.28-29.

- A palimpset in this context probably means a printing plate on which previous incisions had been made and burnished out so that the plate could be used again.

- I am translating Lampsonius’ “amare”, not Hondius’ “amars”, which is not Latin

- Because the Cyclopes worked with hammers.

- See note 1

- The greatest of poets is Virgil, and the episode in question is Aeneid 8, 369-453 and 608-fin. The author seems to think of the images on Aeneas’ shield as paintings (Virgil himself does not say clearly how Vulcan made the pictures).

- “oleo de semine lini”: the same expression in the poem for Jan van Eyck

- This of course merely means “paintings”

- sic. Lampsonius' text in Pictorum aliquot celebrium Germaniae inferioris effigies reads "sive Deos".

- sic. Lamponius' text, cited above, reads 'in gnava'.

- I am reading “sive” for “sine” in line 2, and “gnava” for “guava” in line 4. Both corrections are from Lampsonius.

- This town’s name seems now to be spelt “Aalst” (French: “Alost”).

- sic. see note 2.

- Reading Lampsonius’ “urbes” for Hondius's impossible “urbis”.

- Can be translated as “Caesar” Cf. note on “Emperor” on the text for Albrecht Dürer, Anthony Mor and others

- See note on the text for Bernaert van Orley.

- This seems to mean that Vermeyen showed more skill in painting drapery than was involved in making the drapery itself.

- sic. see note 3.

- sic. see note 4.

- Reading Lampsonius’ “immortali” for Hondius’ “immortalis”. With the latter reading, one would translate “whom Belgium honours with praise [as] immortals”.

- Reading Lampsonius “tantum” for Hondius “tantem” (?), which is not Latin.

- Julius Caesar describes the “Eburones” as a Belgian people in the region “extending from Liège to Aix-la-Chapelle” (Lewis & Short). I cannot say which city the author considers the “urbs Eburonia”. Presumably Dinant itself.

- sic. See note 2.

- This line is unmetrical in the Latin, because Hondius has omitted Lampsonius’ “in” before “illa”. I translate according to Lampsonius.

- This for the Greek Λαμψονίοτε γραφίς. Λαμψονίοτε is apparently the author’s attempt to invent a Greek adjective based on his name. However, the form is bad Greek (better would be Λαμψονιοτὴ) and neither the author’s form nor mine will help the metre. The work by Lampsonius’s pen referred to is his biography of Lambert Lombard: Lamberti Lombardi apud Eburiones pictoris celeberrimi vita, Bruges, 1565.

- In the Latin, “eos” can only refer to “homines”, not “facies”. English cannot do this, so one would have to translate “looking at the people themselves”, vel sim. to avoid ambiguity.

- The renowned portraitist Anthonis Mor (c.1517/20 – c.1576), who was a friend of Lampsonius.

- sic.

- “rura casasque”. See note on the text for Joachim Patinir.

- I am reading Lampsonius’ “arti” for Hondius’ impossible “arte”. are your honesty and candour, and whatever

- The Latin “multa…multum” is equally vague. The sense seems to be that Floris preferred painting many works to expending much energy on any given one.

- The author is referring to Horace, Ars poetica 291, where “limae labor et mora” are recommended for the poet.

- Cf. Propertius, 2.34.65, “cedite Romani scriptores, cedite Grai” (about Virgil’s Aeneid). The implication is that Floris could have been as preeminent among painters as Virgil was among poets.

- Perhaps better to translate “German”.

- Can be translated as “Caesar” Cf. note on “Emperor” on the text for 33. Jan Vermeyen.

- “and sculptor” is not in Lampsonius. No sculpture by Lucas van Leyden is known. The verse shows that sculptor refers to Van Leyden’s activity as an engraver, and engravers marked their work sculpsit. Note, however, the choice of sculptor here and in the titles of 59. Heinrich Aldegrever and 61. Jacob Binck over chalcographus in the titles of 73. Hubert Goltzius and 115. Hendrick Goltzius. Interestingly, Hubert Goltzius is described in the verse as both sculptor and chalcographus, and Hendrick Goltzius is described in the title as chalcographus and in the verse as sculptor. It is possible that the characterization of engraving as ‘sculpture’ was responsive to Vasari’s privileging of sculpture as an art of disegno. At the same time, the appearance of the term chalcographus indicates that engraving was recognized as an art in its own right.

- si qua est ea gloria”: quoted from Virgil, Aeneid 7.4.

- Literally “in our Muse”. Cf. The text on 9. Hubert van Eyck, “Thalia nostra”.

- Sic.

- The Latin reads “quantu”, which is either a misprint for “quantum”, or an attempt (I doubt it) to indicate that the “um” in “quantum” is elided.

- “divivus …orbe Britannus”. Cf. Virgil, Eclogue 1.64, “toto divisos orbe Britannos”. The expression is thenceforth very common for describing the Britons.

- Jan van Leyden