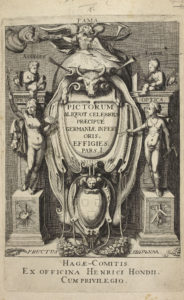

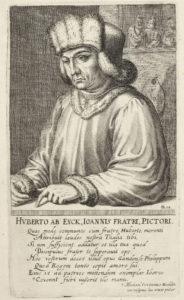

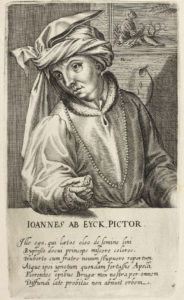

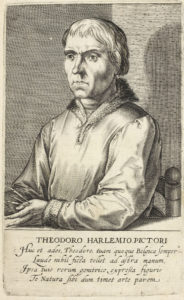

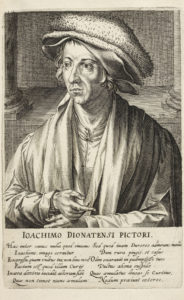

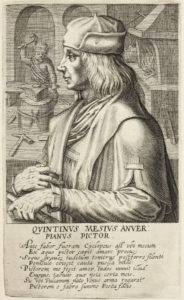

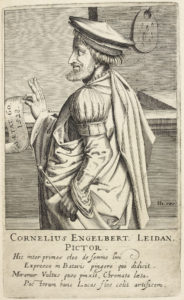

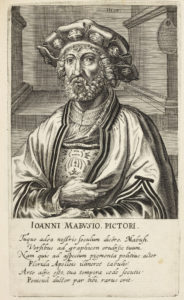

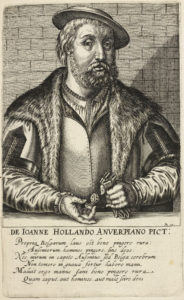

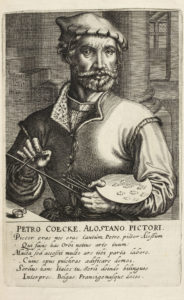

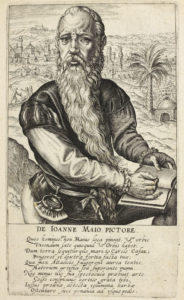

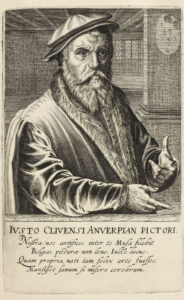

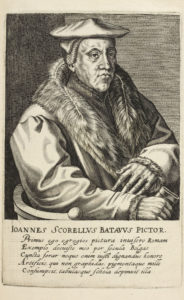

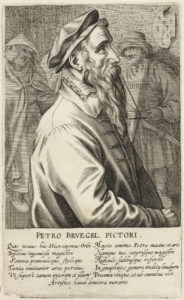

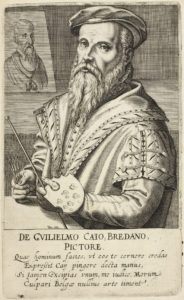

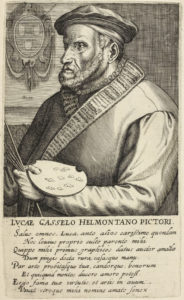

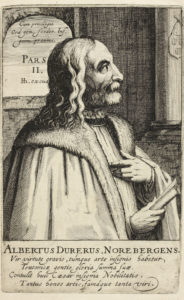

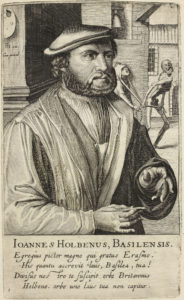

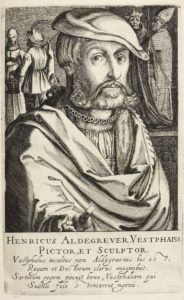

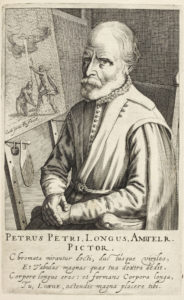

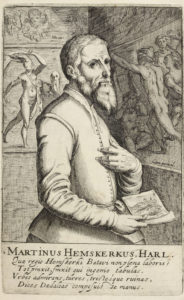

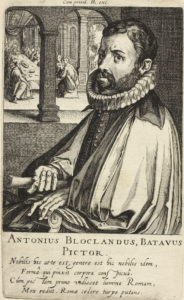

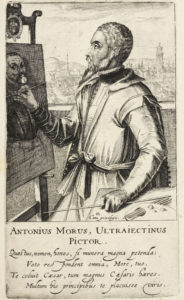

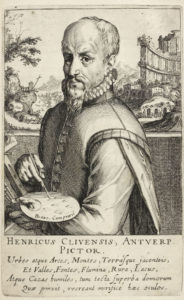

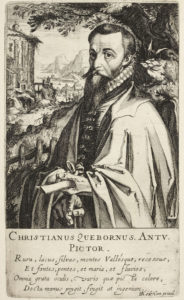

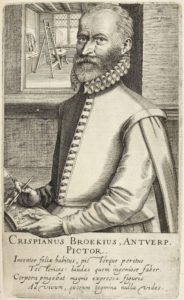

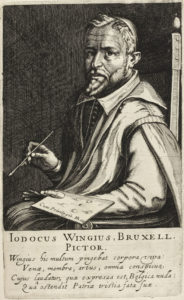

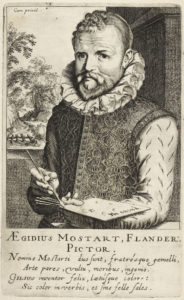

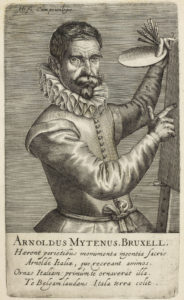

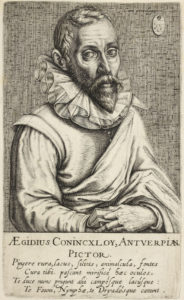

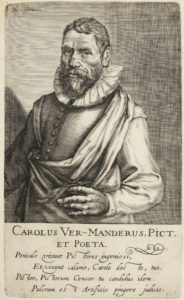

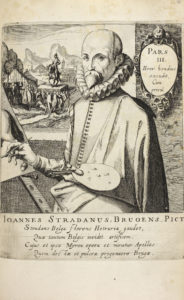

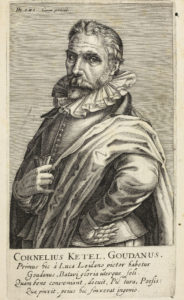

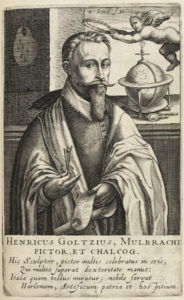

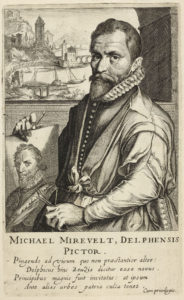

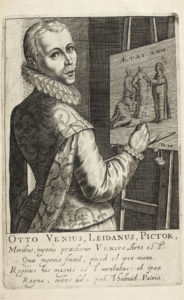

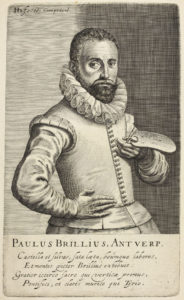

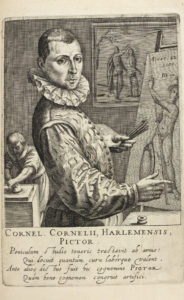

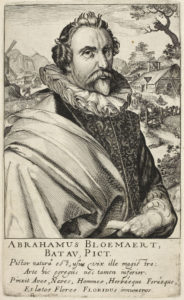

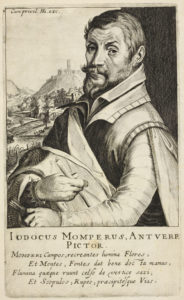

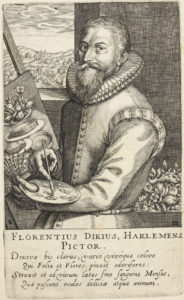

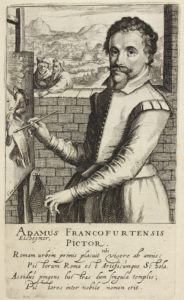

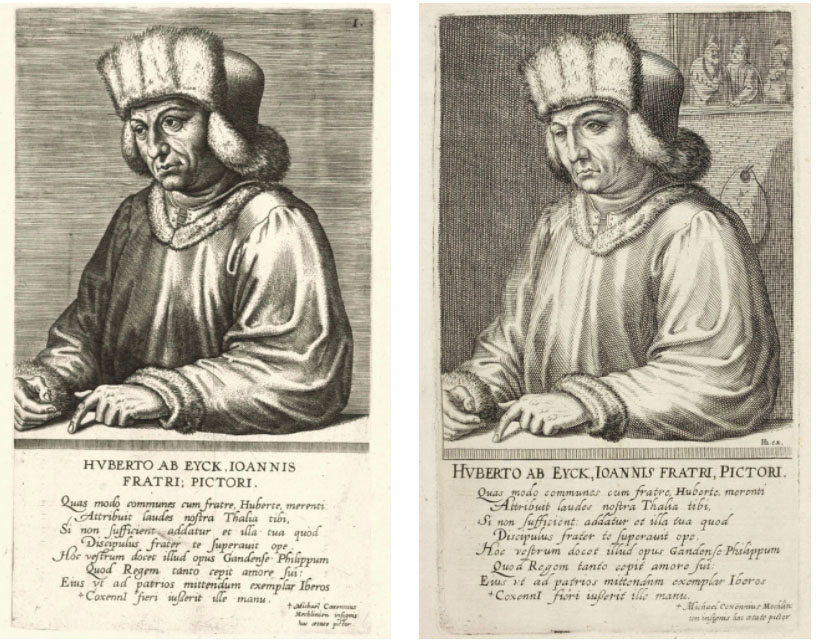

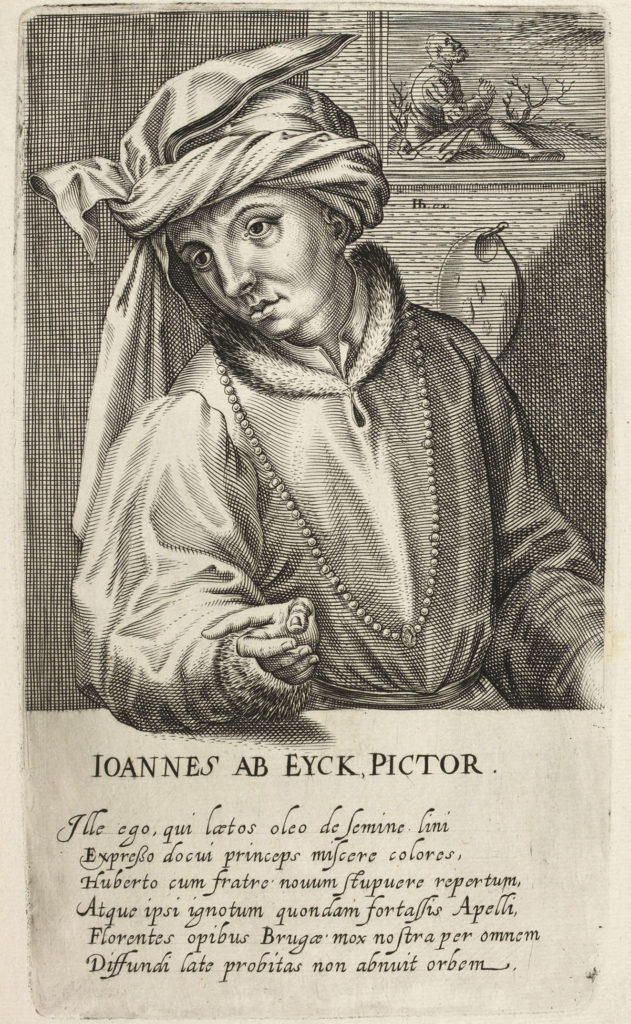

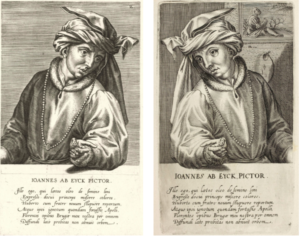

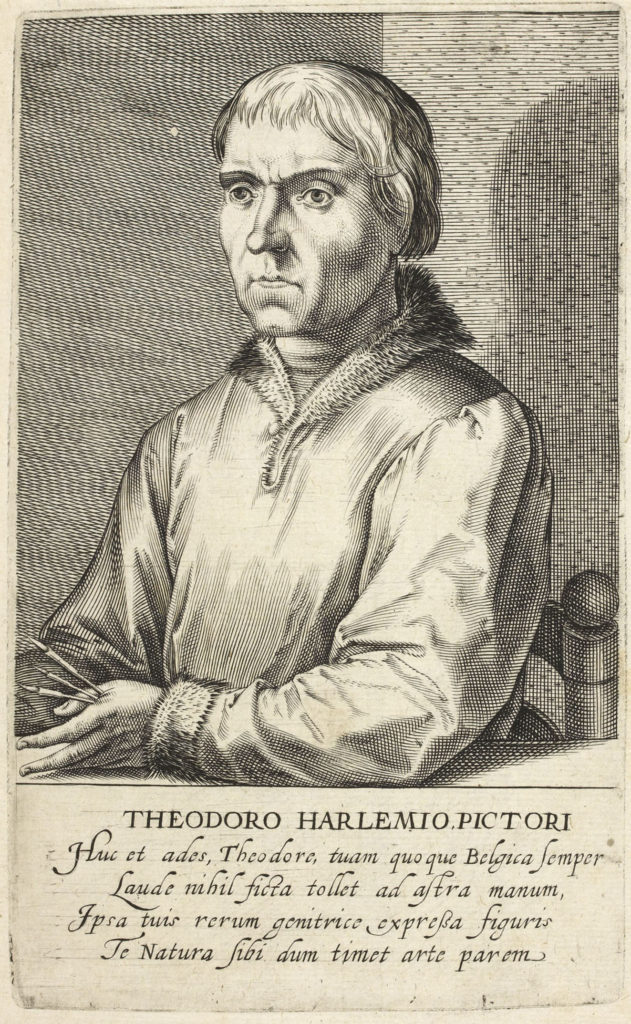

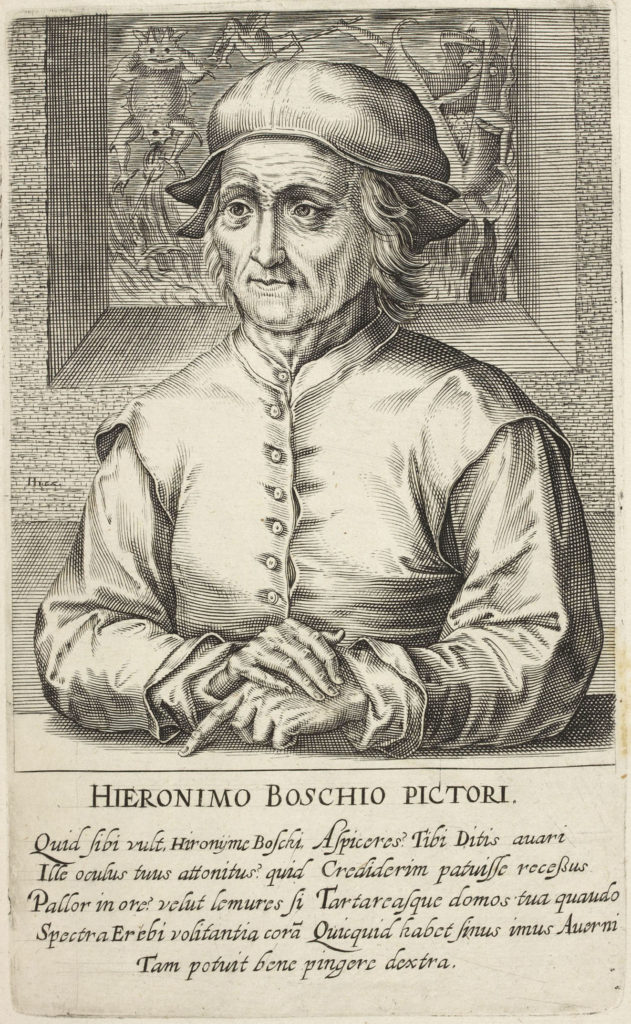

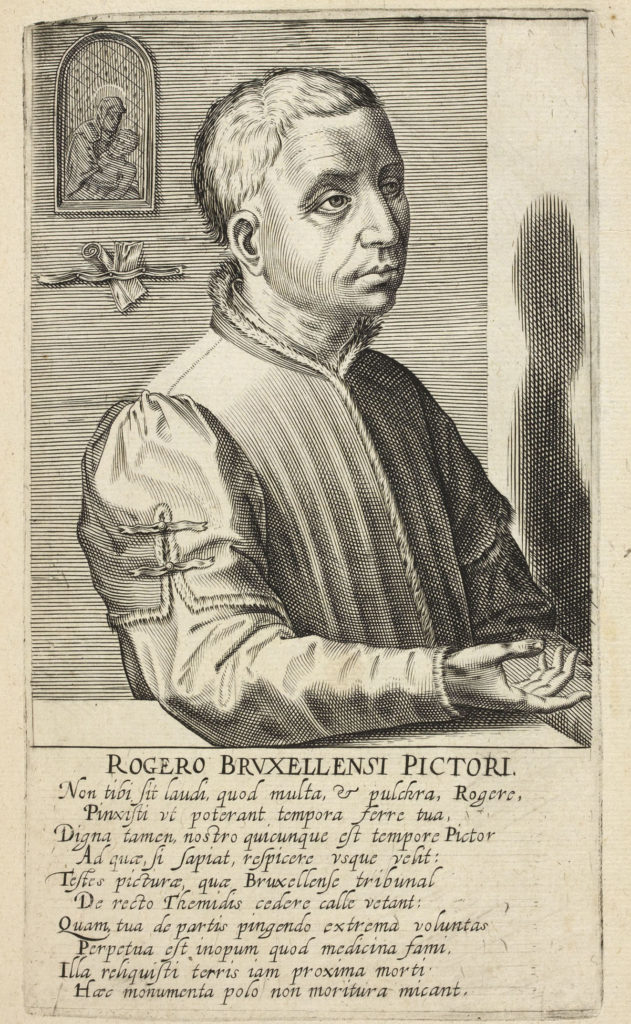

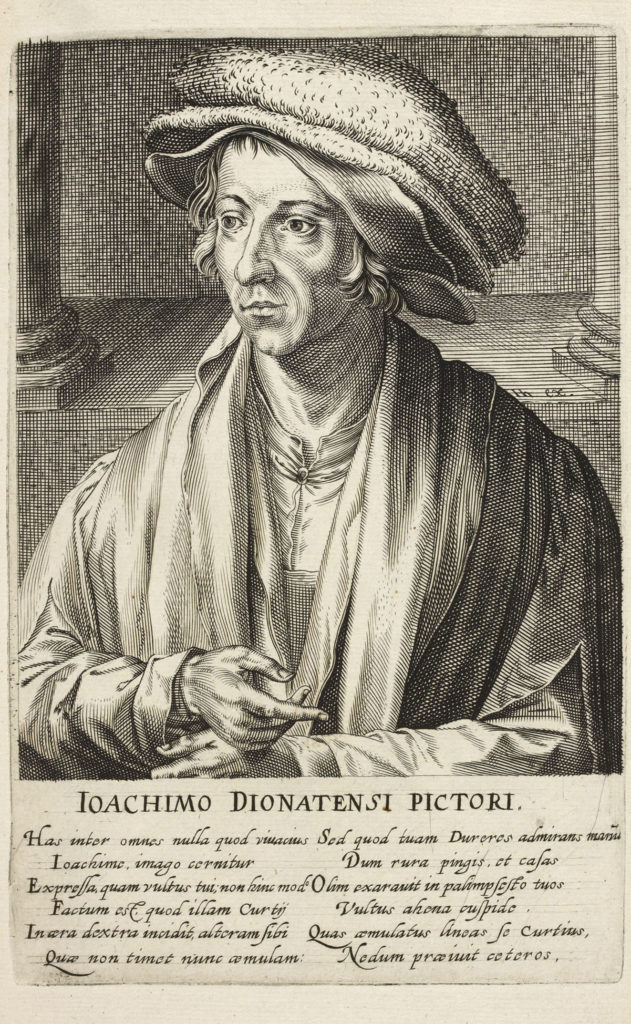

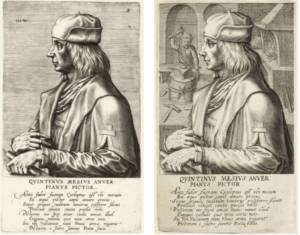

Hendrick Hondius the Elder’s Pictorum aliquot celebrium, præcipué Germaniæ Inferioris, effiges (The Hague, 1610), which contains 68 portrait prints of Netherlandish artists.

You can browse pages below, view a list of the 1610 Hondius pages, or use our turn the page feature to explore the book.

Footnotes:

- “Fructus” can be singular or plural.

- Nadine Orenstein comp., Huigen Leeflang ed., The New Hollstein. Dutch and Flemish Etchings, Engravings and Woodcuts 1450-1700, Simon Frisius 2 vols, Ouderkerk aan den Ijssel, 2008.

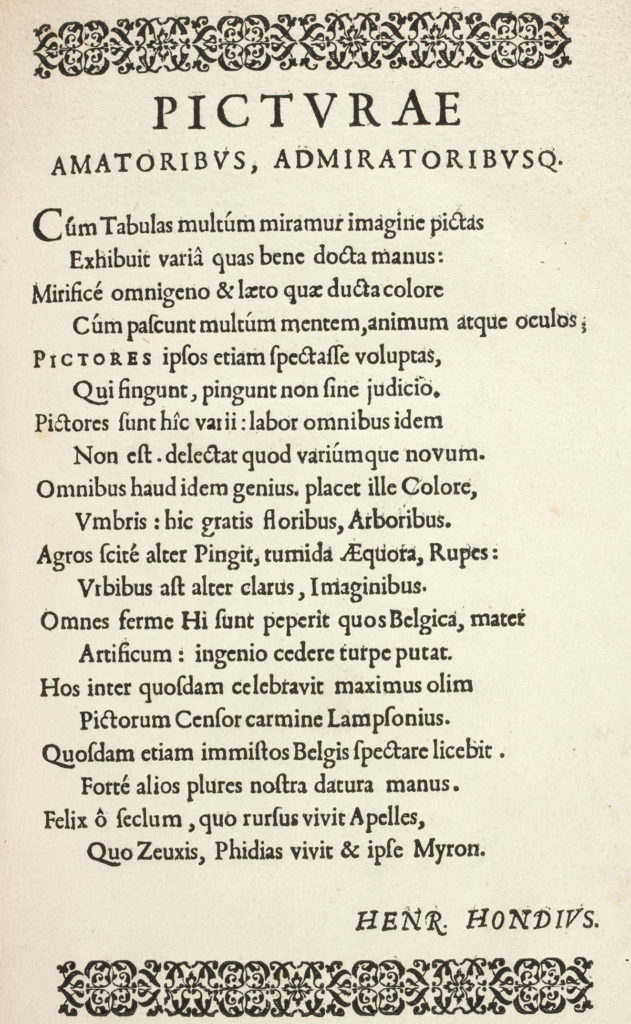

- “quod variumque novum: “literally the solecism “what is and various new pleases”. Cf. also note on Joachim Beuckelaer: “tabulasque culinas”.

- The most probable sense of “imaginibus” here is perhaps “portraits”.

- “Almost all these are those...”. One could also translate “these are almost all the ones...”

- “ingenio cedere turpe putat”. Cf. Anthonie Blocklandt: “Romae cedere turpe putans”.

- "pictorum censor" - the same expression at Karel van Mander, and the very similar "artis censori" at Jacob Binck, apparently of the author.

- One of the muses. Cf. The poem on Lucas van Leyden, “nostrae ...Camenae”.

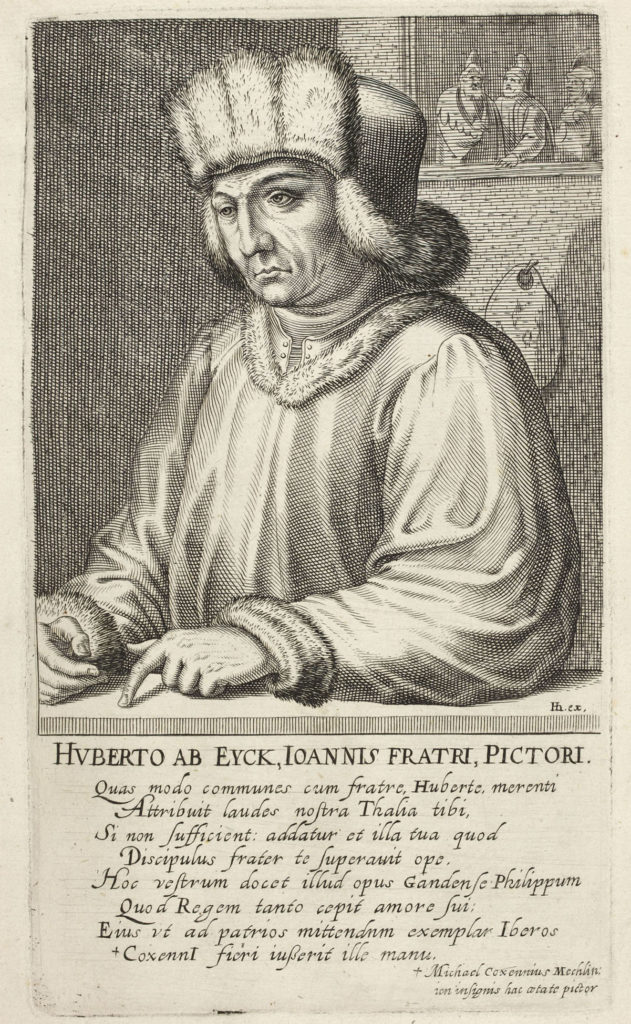

- “ope” could also mean “wealth”. Either way, it’s hard to see (without knowing the context) how Hubert will feel this adds to his praises.

- This for “vestrum”, which is plural, so the work is being credited to both brothers.

- “amore sui” could also mean “love of himself”, but I am presuming that the author is referring to the Lam Gods.

- “ille ego qui” – For the ultimate source of this phrase, see the apocryphal opening lines to the Aeneid, “ille ego qui quondam gracili modulatus avena…”

- “oleo de semine lini”: the same expression in the poem for Cornelis Engebrechtsz.

- This for “probitas”. It is hard to see quite what the author means, but “probitas” to my knowledge always has a moral sense.

- I am taking “rerum genetrice” as qualifying “arte” in the next line. This is awkward, but I cannot see a better solution.

- The entry to the underworld in Virgil’s Aeneid.

- The sense seems to be that Rogier painted as well as he could for his time. Compare to poem on Jan Gossaert

- The point seems to be that Rogier’s paintings will pass away, like all earthly things, whereas his works of mercy will gain him eternal life, and therefore last forever.

- I translate as if “doctissima” agrees with “Bernardus”. This is in fact impossible, as “doctissima” is feminine. It could agree with “aulica … Bruxella”, or be a vocative, addressing Margaret. But neither of these options makes much sense. Nor can it be corrected to “doctissimus” without spoiling the metre.

- The reference, which is found in classical poetry, is to Attalus III of Pergamum, credited with the invention of cloth of gold.

- "me iudice certet". Cf. Virgil, Eclogue 4, 58, "mecum si iudice certet".

- Cornelis Cort (c.1533-1578)

- “rura ... et casas”. The combination (also found in Lucas Gassel below) is from Virgil, Eclogues 2.28-29.

- A palimpset in this context probably means a printing plate on which previous incisions had been made and burnished out so that the plate could be used again.

- I am translating Lampsonius’ “amare”, not Hondius’ “amars”, which is not Latin

- Because the Cyclopes worked with hammers.

- See note 1

- The greatest of poets is Virgil, and the episode in question is Aeneid 8, 369-453 and 608-fin. The author seems to think of the images on Aeneas’ shield as paintings (Virgil himself does not say clearly how Vulcan made the pictures).

- “oleo de semine lini”: the same expression in the poem for Jan van Eyck

- This of course merely means “paintings”

- sic. Lampsonius' text in Pictorum aliquot celebrium Germaniae inferioris effigies reads "sive Deos".

- sic. Lamponius' text, cited above, reads 'in gnava'.

- I am reading “sive” for “sine” in line 2, and “gnava” for “guava” in line 4. Both corrections are from Lampsonius.

- This town’s name seems now to be spelt “Aalst” (French: “Alost”).

- sic. see note 2.

- Reading Lampsonius’ “urbes” for Hondius's impossible “urbis”.

- Can be translated as “Caesar” Cf. note on “Emperor” on the text for Albrecht Dürer, Anthony Mor and others

- See note on the text for Bernaert van Orley.

- This seems to mean that Vermeyen showed more skill in painting drapery than was involved in making the drapery itself.

- sic. see note 3.

- sic. see note 4.

- Reading Lampsonius’ “immortali” for Hondius’ “immortalis”. With the latter reading, one would translate “whom Belgium honours with praise [as] immortals”.

- Reading Lampsonius “tantum” for Hondius “tantem” (?), which is not Latin.

- Julius Caesar describes the “Eburones” as a Belgian people in the region “extending from Liège to Aix-la-Chapelle” (Lewis & Short). I cannot say which city the author considers the “urbs Eburonia”. Presumably Dinant itself.

- sic. See note 2.

- This line is unmetrical in the Latin, because Hondius has omitted Lampsonius’ “in” before “illa”. I translate according to Lampsonius.

- This for the Greek Λαμψονίοτε γραφίς. Λαμψονίοτε is apparently the author’s attempt to invent a Greek adjective based on his name. However, the form is bad Greek (better would be Λαμψονιοτὴ) and neither the author’s form nor mine will help the metre. The work by Lampsonius’s pen referred to is his biography of Lambert Lombard: Lamberti Lombardi apud Eburiones pictoris celeberrimi vita, Bruges, 1565.

- In the Latin, “eos” can only refer to “homines”, not “facies”. English cannot do this, so one would have to translate “looking at the people themselves”, vel sim. to avoid ambiguity.

- The renowned portraitist Anthonis Mor (c.1517/20 – c.1576), who was a friend of Lampsonius.

- sic.

- “rura casasque”. See note on the text for Joachim Patinir.

- I am reading Lampsonius’ “arti” for Hondius’ impossible “arte”. are your honesty and candour, and whatever

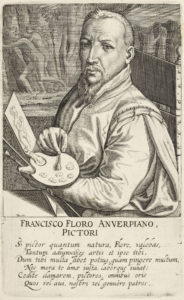

- The Latin “multa…multum” is equally vague. The sense seems to be that Floris preferred painting many works to expending much energy on any given one.

- The author is referring to Horace, Ars poetica 291, where “limae labor et mora” are recommended for the poet.

- Cf. Propertius, 2.34.65, “cedite Romani scriptores, cedite Grai” (about Virgil’s Aeneid). The implication is that Floris could have been as preeminent among painters as Virgil was among poets.

- Perhaps better to translate “German”.

- Can be translated as “Caesar” Cf. note on “Emperor” on the text for 33. Jan Vermeyen.

- “and sculptor” is not in Lampsonius. No sculpture by Lucas van Leyden is known. The verse shows that sculptor refers to Van Leyden’s activity as an engraver, and engravers marked their work sculpsit. Note, however, the choice of sculptor here and in the titles of 59. Heinrich Aldegrever and 61. Jacob Binck over chalcographus in the titles of 73. Hubert Goltzius and 115. Hendrick Goltzius. Interestingly, Hubert Goltzius is described in the verse as both sculptor and chalcographus, and Hendrick Goltzius is described in the title as chalcographus and in the verse as sculptor. It is possible that the characterization of engraving as ‘sculpture’ was responsive to Vasari’s privileging of sculpture as an art of disegno. At the same time, the appearance of the term chalcographus indicates that engraving was recognized as an art in its own right.

- si qua est ea gloria”: quoted from Virgil, Aeneid 7.4.

- Literally “in our Muse”. Cf. The text on 9. Hubert van Eyck, “Thalia nostra”.

- Sic.

- The Latin reads “quantu”, which is either a misprint for “quantum”, or an attempt (I doubt it) to indicate that the “um” in “quantum” is elided.

- “divivus …orbe Britannus”. Cf. Virgil, Eclogue 1.64, “toto divisos orbe Britannos”. The expression is thenceforth very common for describing the Britons.

- Jan van Leyden

- “ingenio... finxit”. Cf. the texts on 67. Maarten van Heemskerk, “finxit qui ingenio”; 83. Christian van den Queborn, “fingit at ingenium”; 111. Cornelius Ketel, “finxerat ingenio”. The combination is common enough in classical Latin (Cicero, Seneca, etc.)

- Does the author here mean “engraved” by “expressa”? Compare note on text for 89. Joos van Winghe.

- I am here translating as if the author had written the ablative “censore” instead of the dative “censori”. For metrical reasons, we can be sure he wrote “censori”, but translating the dative would give the extremely awkward “you will be great for the censor of skill, if he is believed”. I have little doubt the author meant what I have written. – See also the note 5 on “pictorum censor” in Poem to the Lovers and Admirers of Pictures.

- In fact, for “que” we have “q.” with a vertical straight line over it (could conceivably be “qui”).

- “dum vita manebat”. The expression is from Virgil, Aeneid 5.722, 6.608, 6.660.

- “tabulasque culinas”: literally the solecism “whose and paintings kitchens we honour”. Cf. note on “new and varied” in Poem to the Lovers and Admirers of Pictures.

- Imitated from Virgil, Aeneid 1.460, “quae regio in terris nostri non plena laboris?”

- Cf. note on for the text on 61. Jacob Binck.

- “forma” could also be translated “beauty”.

- I suspect the author means “in his first years” (cf. the text for 141. Adam Elsheimer), but I can find no examples of “primo lumine” having this sense.

- Cf. introductory poem and the text for 35. Mathys Cock, “ingenio cedere turpe putat”.

- “pictaeque volucres” comes from Virgil, Aeneid 4.525. Virgil is writing about real birds, and is therefore using “pictae” to mean “coloured, variegated”. But here the term could also have its literal meaning, “painted”, “pinxit and “pictae” are two forms of the same verb (polyptoton).

- Sic.

- The author is apparently attempting to say that Goltzius knew enough about Roman coins and calendars to be a citizen of ancient Rome.

- I read “Algondo” or “Aegondo” in the Latin, but I presume the author must be referring to Philips of Marnix, lord of St. Aldegonde.

- I am reading “ipso” for “ipsa”

- “more fluentis aquae”. The expression is from Ovid, Ars amatoria3.61

- The same motives for art are emphasised in Van Mander’s biography of Mor. As Hessel Miedema points out in his edition of Van Mander’s Schilder-Boeck, they implicitly characterise Mor as lacking in love of art itself, which was regarded as the highest motive.

- “The emperor … the emperor”. Or “Caesar …Caesar”. Cf. note on “Emperor” on the text for 33. Jan Vermeyen. The Emperor in this case is Charles V – and his successor: Philip II.

- Sic.

- “tecta superba”. The expression is from Ovid, Amores 1.6.52.

- “recreant ... oculos”. Cf. the text for 97. Arnold Mytens, “recreant animos”; and 133. Joos de Momper, “recreantes lumina”.

- Cf. note for the text on 61. Jacob Binck.

- This for “vestrum”, which indicates a plural “you”. Unless more than one person is responsible for the image, this usage is bad Latin.

- The author appears to be addressing himself here.

- This for “ad vivum”. But the expression could also mean “from life”. See also the texts for 119. Michael van Mierevelt and 143. Isaac Oliver.

- I am not certain this is what the author means by “expressa”. It could also simply mean “portrayed”, “painted”. Compare note for the text on 61. Jacob Binck.

- Sic. The 'e' of "colore" is written in pencil only. I translate "colore".

- “moribus ingenio” – the same combination at 121. Otto van Veenand in patristic and medieval Latin. Like this poem, van Veen's text adds “arte” to the combination.

- “inventor felix” - the same phrase in the text for 127. Jacques de Gheyn.

- Latin speaks of “colour” in someone’s speech, meaning inventiveness and liveliness. The term can be either laudatory or derogatory.

- Sic, although the syllable needs to be short.

- Abraham Ortelius’ Theatrum orbis terrarum.

- I have ignored the “qui” in the last line, as it makes for Latin too bad to be turned into comprehensible English.

- If this is obscure, one could translate "which was [the fatherland] of learned artists".

- As was 119. Michael van Mierevelt.

- Read "quae"

- Cf. note on the text for 81. Hendrick van Cleef.

- The absence of this "and" in the Latin makes for a very awkward line.

- Sic. the s of "variis" is written in pencil only.

- I am reading “variis” for the text’s “varii”. A space seems to have been left for the missing “s”.

- “pascunt ... oculos” – the same expression in the text for Floris van Dijk.

- "pictorum censor" - see the note on this expression in 5. Poem to the Lovers and Admirers of Pictures.

- See note on “illustrated poems” in 7. ‘To the Lover and Hater of Things Written and Drawn’.

- I gather this is more likely to be Ketel, but the Latin is not clear

- “finxerat”, literally “formed”, may refer to an act of the imagination, or to creative writing.

- Sic.

- Reading “primis” for the text’s impossible “primus”. Cf. also 141. Adam Elsheimer, “primis … ab annis”.

- Or "from life"? See note on text for 87. Crispijn van den Broeck.

- As was 95. Michiel Coxie.

- See note on the text for 91. Gillis Mostaert.

- Presumably for "vertice". primus,

Pontifici, et claris<116Sic - “sata laeta boumque laborum” is from Virgil, Georgics 1.325.

- I am reading “clarus” for “claris”.

- Purple is Tyrian from Homer onward, because it was made in Phoenicia. The reference is presumably to members of some royal family. “et ... Tyrio” is scarcely comprehensible, even after my emendation.

- “inventor felix” – the same phrase in the text on 91.

- "qui artibus egregius" - this clause could refer to either De Gheyn or the "duci belli".

- I have translated both “ille in line 1 and “hic” in line 2 as “he”, as they clearly both refer to Bloemaert. But the use of both pronouns so close together to indicate the same person makes the Latin awkward and confusing.

- This is a pun on Bloemaert’s name.

- i.e. rule over the Western world.

- cf. note on the text for 81. Hendrick van Cleef

- “pascunt oculos” – the same expression in the text for 103. Gillis Coninxloo

- But see the verse, where the implication is that the engraving is by Jan Muller.

- This seems to make sense, although the Latin really requires “you recognize in [or “from”] images the colour which is authentic”.

- sup. lin.

- This for "templis", as is common enough in Renaissance Latin. But of course there are both churches and temples in Rome.

- or "from life"? - see note on 87. Crispijn van den Broeck.

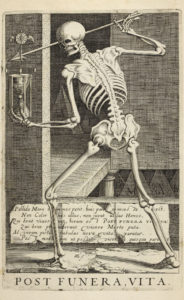

- “pallida mors”: the phrase is from Horace, Odes 1.4.13.

- Reading "tabulis" for "tabula".