Maryam Ala Amjadi transports an 18th-century coffee pot from The Courtauld Gallery’s collections right back to its origins, when the English were awakening to the delights of the caffeine fix. At this time, drinking coffee had become central to the intellectual and social life of cities so removed as London and Isfahan (in modern-day Iran). Read on to learn about the social power of coffee and the practice of debate and camaraderie that it engendered in these disparate cities.

This project was researched and prepared during Maryam’s doctorate, based jointly between the School of English at the University of Kent in Canterbury and the Universidade do Porto, Portugal.

Coffee in Isfahan

Coffee (qahvah, in Arabic and Persian; kahve in Turkish) was a major agricultural product of Yemen and Arabia, which found new markets after their conquest by the Ottomans in the early 16th century. Coffee was exported from Ottoman lands to Persia (now Iran), becoming well established there by the end of the century.

By the end of the 16th century, coffee houses were a vital aspect of the Safavid dynasty’s capital, Isfahan. The major coffeehouses of Isfahan were situated in its main square, Maydan-e Naqsh-e Jahan, at the entrance to the city’s famous bazaar.

Inside the Coffeehouses

The coffeehouses in Isfahan’s main square or maydan were situated next to one another. Large carpeted rooms opened onto the busy square. Customers would sit or recline directly on the carpets while being served coffee and smoking water-pipes.

Storytelling and the performance of folktales and religious accounts were regular activities of the coffeehouse. Safavid coffeehouses were also central in shaping the poetic culture of the age. Customers would often visit coffeehouses to listen to poetry readings and debate. Artists brought drawings to show and discuss in coffeehouses, sometimes in payment for their drinks or in exchange for a poem. Travelling dervishes (mystics) and mullahs (preachers) made regular appearances in coffeehouses.

The tinkling of water from nearby fountains formed the backdrop to the conversations, storytelling and poetry readings in the coffeehouses, while the bubbling sound of water-pipes drifted above. The Safavid ruler Shah Abbas I (1571–1629) engaged in conversation with poets at the ‘Arab’ and ‘Haji-Yusef’ coffeehouses in Isfahan. He occasionally entertained foreign delegates to his court at these coffeehouses, which were decorated specially for royal receptions. The court itself employed a person known as qahvahchi-bashi, whose sole responsibility was to oversee the elaborate preparation of coffee and herbal drinks for the royal court.

From East to West

In the West, knowledge of coffee drinking came through travellers’ accounts. From the late 16th century onwards, Writers would delight in the coffeehouses of Ottoman Constantinople, Aleppo and Baghdad, as well as those in Safavid Isfahan. Despite these effusive reports, it was not until the 1650s that Europe’s first coffeehouses began to spring up in Oxford and London.

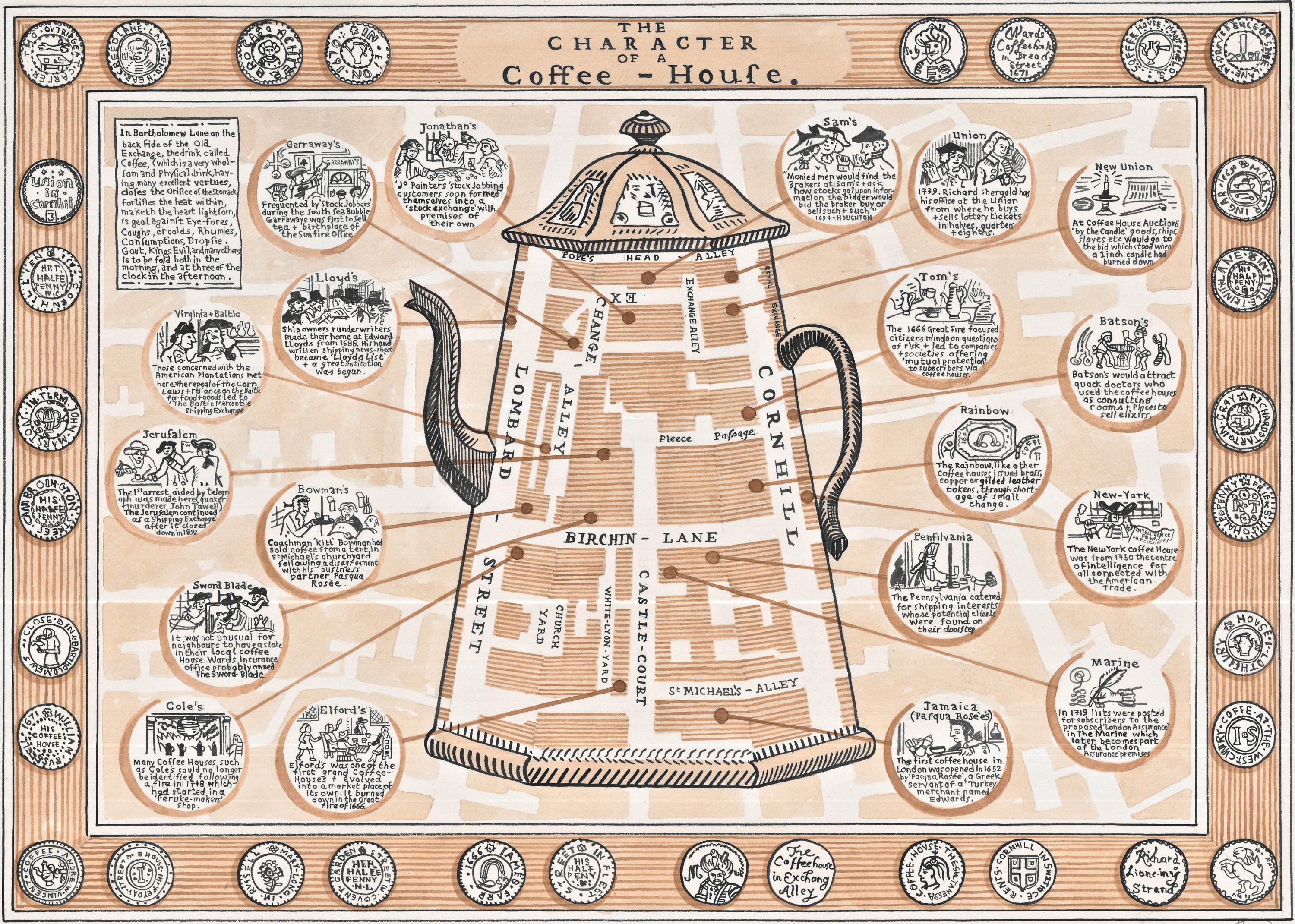

Pasqua Rosée’s (fl. 1651–56) coffeehouse at St Michael’s Alley, Cornhill, in the city of London, was opened around 1652. His employer, Daniel Edwards, facilitated this venture, capitalising on his position as a merchant of the English Levant Company. Both Edwards, who imported the raw material into London, and Rosée, his servant, had first-hand experience of coffee culture in the Ottoman trading city of Smyrna (modern Izmir). Their coffeehouse sought to commercialise and replicate what they had seen abroad, but in the mercantile centre of London.

The association of coffee with the Ottoman Empire predominated in the visual culture surrounding coffee for many years. Early coffeehouses in England were routinely decorated with a painted representation of the turbaned head of a Turkish man at the entrance.

As was the practice in the East, coffee had to be drunk very hot. This was a novelty in Europe, which created the need for new equipment and wares for coffee-drinking and preparation. The first coffee pots in England were made of tin or copper and imitated the look of Turkish pots with their high domed conical lids.

While plain coffee pots were used in public coffeehouses, silver coffee pots of the type that The Courtauld Gallery owns were prized possessions in the home, and were brought out to display the taste and wealth of their owners. The present coffee pot was designed and made by Augustin Courtauld (1685/6–1751), a craftsman from the Protestant community of Huguenots that fled religious persecution in France and established themselves in London in the late 1600s.

Georgian London’s Coffeehouses

The 17th and 18th-century coffeehouse was a hub of intellectual and social engagement. Customers of relatively diverse social backgrounds would come to read newspapers, debate and comment on world events; tradesmen would strike business deals and travellers would exchange bits of news. These activities are outlined in a broadside printed in 1674, entitled Rules and Orders of the Coffee-house:

Enter, sirs, freely, but first, if you please,

Peruse our civil orders, which are these.

First, gentry, tradesmen, all are welcome hither,

And may without affront sit down together:

Pre-eminence of place none here should mind,

But take the next fit seat that he can find…

Coffeehouses were known as ‘penny universities’ because clients including students, artists, writers, merchants and businessmen, were charged a penny as an entrance fee, which covered the drink, newspapers, pamphlets and the latest news and gossip.

Some of the greatest English writers of the early modern period, such as John Dryden (1631–1700), Jonathan Swift (1667–1745), Joseph Addison (1672–1719) and Samuel Johnson (1709–84), were regulars at coffeehouses and their presence attracted further customers.

Coffeehouses had vocal supporters and detractors, and numerous pamphlets were published either condemning the drink — for example, claiming it caused impotence — or praising its restorative virtues. Satirists criticized the kinds of behaviours occurring in coffeehouses: gabbling, gossiping, wheedling and idleness were four foibles thought to be engendered by drinking coffee. Coffeehouses were also, more seriously, potential breeding grounds for political rebellion, where the ‘seeds of sedition’ (M. P., A Character of Coffee and Coffee-Houses, 1661) were planted. Charles II (1630–85) famously tried to stifle their potential for dissent by issuing a ban on coffeehouses in 1675. The ban was lifted shortly thereafter, following public outcry.