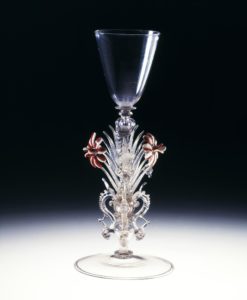

Victoria Druce dives into a fascinating era of European glass-making, as she investigates a Venetian-style 16th-century goblet and an English wine glass from c. 1770. These objects from The Courtauld Gallery open up a world of craft and science that is integral to glass production. As we will see, chemical balance and honed techniques lie behind the creation of these striking vessels.

Victoria worked on this project during her Masters in Science Communication at Imperial College London.

From Venice to London: The Movement of Glass Technology

By the 13th century Venice was famous for its glass. The Venetian lagoon was in prime position for international trade and had a monopoly on luxury glassware. The Venetian Republic guarded its technology by restricting the movement and freedoms of its craftsmen, confining glass-makers and their industry to the island of Murano.

Despite strict regulations, many Venetians did leave Murano. By the 16th century, lured by the promise of greater freedoms and emerging markets in new locations, Italians had settled in new glass-making centres across Europe. Initially craftsmen moved to Antwerp, which was one of the most important ports on the European continent.

Many glass-blowers settled there and established glasshouses, unable to return to their homeland for fear of punishment. Some continued further north towards England, including the influential glass-maker Jean Carré (d. 1572) in 1567, as well as Jacob Verzelini the Elder (1522–1606), who took over Carré’s glasshouse when he died. The Muranese brought their skills and knowledge with them to these new destinations, where they trained local people in their craft and made glass in the Venetian style, known as façon de venise. The glass made in these European locations was just as delicate and luxurious as the glass produced in Venice.

A New Material: Lead Glass

For centuries, the influence of Venice had stretched far and wide. But by the late 1600s the Venetian dominance in glass technology began to fade, as a revolutionary English recipe, created in 1674, became popular. George Ravenscroft (1632–83) is credited with the invention of lead glass (then known as flint glass, owing to the use of powdered flint as silica) in which lead oxide was added to the molten glass batch. Lead glass was not only stronger and more durable but also clearer than Venetian glass. The large proportion of lead in the glass, up to 40% for some objects, means it is very stable. The network of molecules in the glass is tightly held together so that when the glass is struck, the network cannot absorb the shock and instead vibrates in place. This structure gives lead glass a characteristic ring when tapped. This satisfying tone is absent in Venetian glass.

Lead glass is less viscous and takes much longer to cool and solidify than the façon de Venise glass. This trait dictates the stylistic possibilities of lead glass. The fanciful designs of Venice gave way to more practical and straightforward shapes. Individual glasses were now constructed from three components: the foot, the stem and the bowl. These parts were made separately and then joined together in a production line, in keeping with the industrialisation taking place at the time. Ornament was added to the glasses either by engraving patterns onto them or in the form of decorative stems. Air twist stems were briefly popular around 1750, but were soon overtaken by opaque twist stems (also known as cotton twist). English glass-blowers used the filigree technique invented in the 16th century to produce increasingly complex patterns in the stems of glasses. One column of threads was sometimes surrounded by another, creating beautifully intricate interweaving designs.

Patterns and Processes

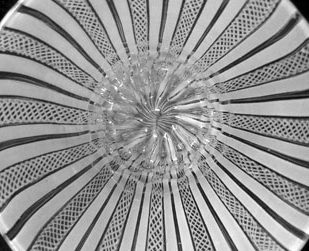

In 1527, brothers Filippo and Bernardo Catani (also known as the Sirena brothers, after their glassworks) patented a technique known as filigrana. The technique used white glass called lattimo, named after the Italian for milk (‘latte’), which was integrated into objects to create beautifully intricate patterns. The opaque glass was produced by adding tin and lead to the molten batch. These delicate white designs highlighted the art of the craftsmen and began to replace the gold ornamentation of the past. Soon, filigrana decoration became highly fashionable and associated with elevated members of society.

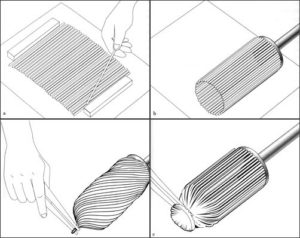

To produce these complex patterns, white canes of glass would be laid in a mould and alternated with colourless glass canes. The glassblower would roll a colourless glass bulb over the canes to pick them up and then ‘marver’ them. Marvering involves a rolling the canes while they are attached to the bulb, in order to smoothen the surface of the glass and embed the white canes in clear glass. This pattern of simple stripes was called a fili. More complex patterns followed, including a retorti, where canes were twisted into a spiral.

A variant on this technique that seems to have come slightly later involved creating a cylinder of canes by laying them in a sheet which was heated in the furnace before rolling the canes around the circumference of a clear glass collar. The canes would be fused into a cylindrical shape, which could then be expertly worked by the craftsman.

Craft and Composition

Venetian glass is made of two major components: silica and flux. The Venetians used crushed pebbles from the Ticino River as their source of silica. The flux, which helps the silica to melt at a lower temperature, came from the ash of burned coastal plants. The ash also contained impurities which acted as stabilisers in the glass, without which the glass would be fragile and vulnerable to moisture in the air. Typically the stabiliser is lime, known to chemists as calcium oxide. There is little evidence that the Venetians were aware that these stabilisers perform a significant function, but their naturally occuring presence in the flux was crucial nevertheless. One undesirable side effect of ash was that certain among its compounds lent the glass a coloured hue rather than the crystal clarity that the Venetians sought.

A recipe for cristallo glass, invented in the 1450s by Angelo Barovier (d. 1480), promised better transparency. This quality was achieved through purifying the ash, and thus removing the compounds that would colour glass. This solution was imperfect, as the purification process also inadvertently removed the naturally-occurring stabilisers in the ash. The resulting glass was therefore very fragile and prone to glass disease. Much academic debate revolves around whether or not cristallo glass has survived. Some experts claim that it is unlikely that large quantities of such fragile glass would have survived unscathed through the centuries. Regardless of this perspective, many museum labels do refer to their glasses as cristallo. In so doing, they may simply be describing the clear and feather-light nature of the glass rather than referencing Barovier’s purification technique.

Although much scientific research is currently underway on glass, it is still difficult to distinguish Muranese glass from glass made in northern European glass-making centres. Venetians who moved to northern Europe brought their recipes with them and continued to use the same raw materials, meaning that glasses made in Europe and in Venice have very similar chemical compositions. These recipes remained popular across Europe until the invention of lead glass in the late 17th century.

Bibliography

Charleston, Robert Jesse. English Glass and the Glass used in England, circa 400–1940. London: Allen & Unwin, 1984.

Higgott Suzanne. The Wallace Collection: Catalogue of Glass and Limoges Painted Enamels. London: Trustees of the Wallace Collection, 2011.

Janssens Koen H. A. Modern Methods for Analysing Archaeological and Historical Glass, 2 Vols. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley and Sons, 2013.

Liefkes, Reino, ed. Glass. London: V&A Publications, 1997.

McCray, W. Patrick. Glassmaking in Renaissance Venice: The Fragile Craft. Farnham: Ashgate Publishing Limited, 1999.

Powell, Harry James. Glass-Making in England. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1923.

Rasmussen Seth C. How Glass Changed the World: The History and Chemistry of Glass from Antiquity to the 13th Century. Berlin: Springer-Verlag, 2012.

Tait, Hugh. The Golden Age of Venetian Glass. London: British Museum publications, 1979.