We’ve been busy working on our dissertations, so we’re taking the opportunity to get to know the current MA Documenting Fashion students. Here, Megan discusses David Bowie, Paris is Burning, and her early fashion influences.

What is your dissertation about? What prompted you to choose this subject?

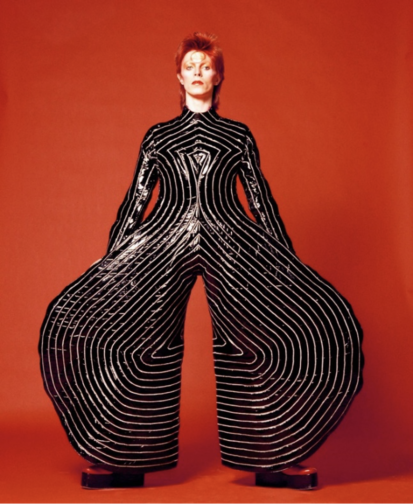

My dissertation is about David Bowie… kind of. I’m looking at the personae of Ziggy Stardust and Aladdin Sane, focusing on three sources: Brian Duffy’s photoshoot in January 1973, Masayoshi Sukita’s photoshoot in February 1973, and D. A. Pennebaker’s documentary Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars (filmed July 1973).

I was initially inspired to research this area after learning about the close connection between Bowie and Japan, which made me wonder about the various influences that collaboratively produced his iconic personae. The incredible glam rock fashion of his Ziggy Stardust and Aladdin Sane period made the choice of which area to focus on pretty easy. I’m really enjoying the research, as it’s allowing me to dig under the surface of visual media and find a whole network beneath. Along with Duffy, Sukita, and Pennebaker, I’ve been researching fashion designers Kansai Yamamoto and Freddie Burretti, make-up artist Pierre La Roche and mime artist Lindsay Kemp. My main realisation has been that there is an infinite list of contributors, collaborators, and influences that came together to produce the Ziggy Stardust and Aladdin Sane imagery that we know so well. Even a rice cooker gets a mention for being relevant! It’s also been really interesting to trace the sources and their uses in various forms – my favourite of which being the Barbie doll dressed and marketed to recreate an image from the Sukita shoot.

What is your favourite thing you’ve written/worked on/researched this year?

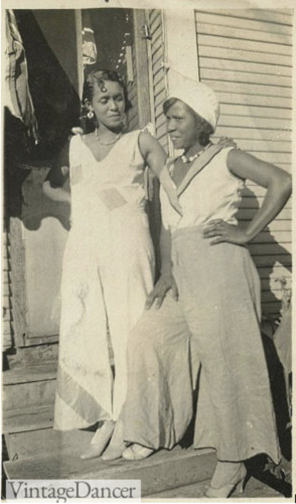

My favourite thing would have to be my first essay, which was about the wearing of fur in Jennie Livingstone’s Paris is Burning, a documentary filmed in the late 1980s about the New York ballroom scene. I researched the history of fur as a material in fashion, and the social and cultural reasons fur may be worn in different contexts. Paris is Burning was a particularly interesting lens to view this through, as tensions between fur as a marker of distinction and anti-fur campaigns were dramatically rising. Not only that, but I could bring in a lot on gender and fashion – my favourite topic!

What are you wearing today?

Today I am wearing periwinkle blue trousers, a white t-shirt and a brown check jacket. The trousers are the most recent thing I’ve bought, I found them on Depop and am loving them. The t-shirt was given to me as merchandise when I worked on an event a few years ago, and it’s become a staple of my wardrobe. The jacket is originally from Motel, but I got it from a charity shop in Angel for £7. On my feet are a pair of Flamingos’ Life trainers, bought second-hand on Ebay. I’d really recommend Flamingos’ Life – they are plant-based, comfy, and don’t slip off the backs of my feet as I walk along.

As you probably noticed from that description, most of my clothing these days comes from some kind of second-hand source. I started trying to avoid fast fashion about 5 years ago and am really happy with the eclectic wardrobe I have built since. I’ve dabbled with making my own clothes, and the new series of Sewing Bee is inspiring me to dedicate more time to that this summer! I have been desperate for a brightly coloured co-ord suit that fits my body (Zara seems to think I need an extra 6 inches of torso?), so that’s what I’ll be aiming to perfect first.

This MA has really solidified my belief that clothes aren’t everything, but they’re a heck of a lot more than ‘just’ clothes. They are a way for us to customise this character we have been given, to make our day more comfortable, to support our lifestyle and to surround ourselves with softness and colour (at least, these are my main priorities).

Do you have an early fashion memory to share?

A glowstick exploding all over my favourite lilac crushed-velvet tank top, age 6! I never fully recovered, and today I own a turquoise crushed-velvet strappy crop top… I actually had forgotten all about the glowstick incident until I thought about how to answer this question, and hadn’t made the connection between that top of 17 years ago and the crop top I now own and wear on nights out. Oh dear.

In terms of fashion media, I have strong memories of media which I think must have come from my big sister, because I was almost certainly too young to follow these when I first watched them. Charlie’s Angels (2000) has Drew Barrymore playing Dylan, and her blue-eyeshadowed rock-chic look definitely inspired me for better or worse. Ugly Betty (2006-2010) and The Rocky Horror Picture Show (1975) also felt like defining moments where I became aware of fashion. They were also both, in their own ways, trailblazing forms of media. I’m glad I could see their comedy, drama, and representation from an early age. (Special shout-out to Pierre La Roche, mentioned earlier, who also did the make-up for Rocky Horror and has been a feature of many of my interests without my realising for all these years. More people should know about him!)

If I’ve got my timings right, then this is my final post for this blog! I’ve really enjoyed my time writing here and reading the wonderful words of my course mates. If you want to see more of what I’m getting up to then my Instagram is @megangalleria – I mostly post about museum, gallery, fashion and photography related things.

All the best!

By Megan Stevenson

Images:

https://www.snapgaleries.com/portfolio-items/david-bowie-by-masayoshi-sukita

https://www.hamleys.com/barbie-david-bowie-doll

Livingstone, Jennie. Paris is Burning, cinematographer Paul Gibson (1990; New York: Second Sight Films Ltd, 2009), DVD

https://screenrant.com/charlies-angels-every-angel-ranked/

https://rockyhorrorpictureshowpics.tumblr.com/image/1246180119