We’ve been busy working on our dissertations, so we’re taking the opportunity to get to know the current MA Documenting Fashion students. Here, Georgina discusses Vogue, her scented virtual exhibition and fairy wings.

What is your dissertation about? What prompted you to choose this subject?

My dissertation is on Audrey Withers OBE, who was the editor of British Vogue between 1940 and 1960, having first joined the magazine as a sub-editor in 1931. I was introduced to Audrey Withers’ work through Julie Summers’ book and online talk on Dressed For War in late 2020. During the talk, hosted by Somerville College, I learnt that Audrey Withers and I had shared the same undergraduate college, and, yet I had never heard of her name despite her many achievements and my pre-existing interest in fashion (with a keen interest in fashion magazines). I immediately became fascinated by her life and work, wanting to learn more about the tensions between her public and private personas – Audrey Withers was as a notoriously private character – and it was this which ultimately inspired me to apply for the Documenting Fashion MA at the Courtauld. Through my dissertation, I’m enjoying playing the part of detective, trying to uncover more information about Audrey Withers through her private correspondence, workplace memos and newspaper cuttings, as well as undo the misconceptions surrounding her, such as she herself became ‘interested in Vogue magazine when an undergraduate at Somerville College, Oxford,’ as written in a Norwood News article of 1951. In fact, Audrey Withers was largely uninterested in fashion and instead ‘achieved her results by sheer intelligence’ in the words of Harry Yoxall, the chairman of Condé Nast. My dissertation will focus on her private and public lives and how they were designed to remain entirely separate, but that Audrey Withers’ role at Vogue required them to overlap at points, with family friends such as Paul Nash writing articles on all manner of things.

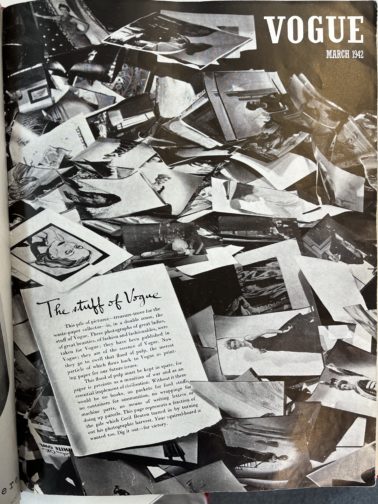

Additionally, I was fascinated to learn how Audrey Withers and Cecil Beaton destroyed the entire paper and photographic archive of British Vogue for 1942’s March issue (below) in response to the Paper Salvage effort and in the face of unimaginable hardship. I believe the coupled nobility and arrogance in this action – which reacted to contemporary uncertainty at the expense of future study – serves as an example of the undeniable tension behind justifying perceived ‘frivolities’ in an era of necessity as well as securing Audrey Withers’ status as a largely anonymous and unknown figure.

What is your favourite thing that you’ve written/worked on/researched this year?

I’m loving my dissertation – especially as it is something I’ve been mulling over since last summer – but I really enjoyed working on my virtual exhibition, which explored the power of perfume. Perfume is capable of so much: it has the power to evoke forgotten moments; perfume acts as a designer’s signature – yet invisible – autograph, the list could go on… What I’ve loved about this project was its focus on creating a visual argument. Unlike an academic essay where you might presume certain knowledge and expertise on behalf of the reader, I had to consider how to pitch each element to a wide variety of visitors in order to give them the best experience possible. For instance, I used text panels to introduce each section and broader themes, whereas the sample exhibition catalogue entry allowed for a more in-depth analysis.

I wanted to situate perfume within a retail space, reinforcing perfume’s relationship to commercial practices, and chose to set it in the historic Liberty Department Store in London. In keeping with the idea of it as a fantasy exhibition, I kept on imagining I was in ‘The Sims’ world each time I was working on my floor plan, visualising how a Sim character would walk through the exhibition space. I wanted to create an immersive, multi-sensory experience, and decided on a commissioned and interactive sensory wall, serving baked goods (and cocktails!) to create three ‘miniverses’ to reflect the perfumes and designers on display: Elsa Schiaparelli’s Shocking, Yves Saint Laurent’s Opium and Tom Ford’s Tuscan Leather. I found considering perfume’s position as simultaneously immaterial and material particularly fascinating and incorporated that into my layout.

What are you wearing today?

Recently, I’ve found that I’m wearing a ‘uniform’, which normally consists of jeans, a simple top, a fun statement blazer or coat and a bright red lip. Today, I’m wearing a pair of denim blue Levi’s, an M&S black thermal top (not so chic, but I FEEL the cold), my cherished checked old Celine blazer from Vestiaire Collective and a pair of slightly battered Axel Arigato trainers, plus my go-to vintage Mulberry laptop bag, which I nabbed from my mother. And, of course, my signature red lip. I’m also having a bit of a jewellery moment, so have layered it with a couple of Alighieri necklaces (including the ‘Invisible Compass’ as I’m always getting lost!), a gorgeous Katie Mullally Irish Coin Charm featuring an Irish hare (I’m born Year of the Rabbit which I feel is close enough) and an amber necklace bought in Edinburgh by two of my dearest friends for my birthday last year. I’m also wearing a pair of Motley X Alice Cicolini earrings and my usual rings, including one from my mother and a Gracie J prototype tear ring. It’s been a research day, which started with an exciting trip to Vogue House to meet with Julie Summers, where we talked about our love for Audrey Withers, and I was lucky enough to take a quick peek at some of the Vogue archives from the 1940s and 1950s. I then had lunch with a friend and have since been busy in the London College of Fashion Library looking at more Vogue archives where I bumped into fellow MA student, Megan, before heading home for a relaxed evening!

Do you have an early fashion memory to share?

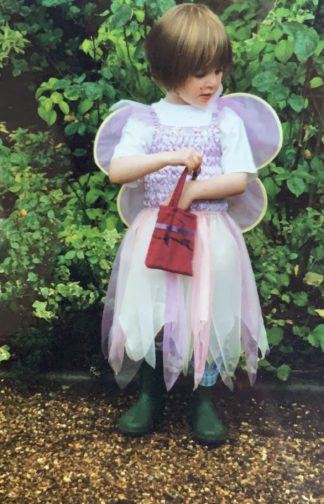

When I was a child, there was a time where all I would wear was a dress with a tutu skirt, fairy wings, and green wellington boots. And jeans underneath if it was cold. Occasionally, if I was feeling very daring, I might try to pinch my mother’s clip on earrings to complete the look… From an early age, my mother had been quite happy for me to choose my own outfits, barring the occasional family event, and so I’d turn up to nursery dressed as a fairy. Complete with a little handbag with everything a fairy might need for the day, namely bubbles and a glitter pen.

As I would wear this outfit day in and day out, I must’ve worn it on the day we had an art lesson as my mother ended up receiving a call from the school. Initially assuming it was about one of my brothers who was constantly misbehaving, it was a surprise to hear that it was about how I had refused to take off my fairy wings when asked. Though the teacher was seemingly only concerned they’d get mucky during the arts and crafts activities, I continued to refuse to take them off and they were unable to put my painting overalls on. While neither my mother or I can remember the precise outcome, or whether I agreed to take my fairy wings off – even momentarily to put the apron on – I’d like to think that a compromise was eventually made, and I succumbed to reason. But knowing how stubborn children can be, there’s certainly a chance that I refused to cooperate.

In the photo below, it’s funny how the core of many of my outfits remains the same, even nearly two decades on. I often wear a white t-shirt and jeans, and the tutu dress and fairy wings have simply been replaced with a statement jacket. It would seem that there’s a part of me that still wants to be a fairy.