We’ve been busy working on our dissertations, so we’re taking the opportunity to get to know the current MA Documenting Fashion students. Here, Ipek discusses the construction of the modern Turkish women, Grace Kelly, Wiener Werkstatte designs and a special red velvet dress.

What is your dissertation about?

My dissertation is about the modern Turkish women of the 1930s, how she reinvented herself through fashion in 1930s Turkey, a period when the Turkish Republic had just been established and the country had been under a very drastic social change, a modernisation period. Through my deep dive into the archives, I have found a variety of amazing magazines as Fashion Album and Seven Days from 1930s Turkey with illustrations and photographs of tailors and designs that gave an idea of how fashions of the West were reinterpreted by the Turkish women in a quest to take control over their self-fashioning.

I guess my interest in this topic first and foremost stemmed from the fact that I never got a chance to study this subject at school as it was quickly brushed over to move on with the curriculum, which often is the case in high school. But also, after studying the Western fashions and history for a year I started to think of how my culture compares to the developments in the West and how did it respond. It was incredibly interesting to analyse a completely different ideology and thought processes that surrounded fashion in Turkey.

Turkey is often thought of in an Orientalist and ‘exotic’ fantasy context which stemmed from various Orientalist painters of the West from the 1800s as Delacroix and John Frederick Louis often discussed in art history. However, although the West is often regarded as the centre of thought, fashion and all else, the meanings that fashion spurs differ greatly in different cultures. For the modern Turkish women, it was an opportunity to harmonise both symbols of Turkish culture with the fashions of the ‘modern’ West to carve out her silhouette, establish her now empowered status in Turkish society after being veiled and thus physically, metaphorically invisible and absent from society for far too long.

The image below is one of many photographs that show the newfound confidence of the modern Turkish woman in her self-fashioning. Here students of the Istanbul City Theatre hold on tightly to one another whilst getting out of class, confidently walking across the gardens of the theatre, displaying their unveiled hair and highly fashionable dresses.

Figure 1: Kurt and Margot Lubinski, Drama Students of Istanbul City Theatre, 1930s, National Geographic Bogazici University Archive.

Do you have an early fashion memory to share?

I guess I can trace it back to New Year’s evening of the year 2000. It is probably also the earliest memory that I have. I was 4 years old. The whole family had gathered at my mom’s uncle’s house to celebrate the evening and it was most likely the biggest party that I had ever been to up until the age of 4. I distinctly remember that my mother wanted me to look extra ‘chic’ for that night so she dressed me in this gorgeous red velvet dress that had a bow pinned at the back. I still remember the texture of the smooth velvet against my skin. I felt so incredibly special in this dress with my matching red shiny shoes, a matching red bow on my hair and I knew in my heart that it was going to be a special evening. It turned out to be nothing less than that as I remember it to this day. Although my feet hurt, it was way past my bedtime, and the bow’s pin started to jab my back a bit towards the end of the night, I felt like a star and it was all worth it as many relatives complimented the dress and ‘my impeccable style’. What more can a 4-year-old girl ask for other than going to bed past bedtime hours (which was 08:00 pm), eat as much cake as she likes and sit in a gorgeous red velvet dress while everyone complements her? It was a night to remember for sure. Sadly, I have outgrown that dress and although the dress was given to a younger cousin to enjoy, I’ve kept the shoes, like Cinderella and it still reminds me of that night and how I felt. This photograph of me from that night, staring at the cake while fidgeting with the buttons of my cuff as everyone stares at the camera, probably shows my two true passions in life: chocolate cake and dress.

Which outfit from dress history do you wish you could wear?

Old Hollywood has a timeless quality, grace and elegance that I find myself thinking about often as it’s an essence that seems to be lacking in the 21st century. There are so many iconic fashion moments in any movie featuring Grace Kelly but I have absolutely loved this blue chiffon dress from Alfred Hitchcock’s To Catch a Thief (1955) where Kelly stars opposite Cary Grant. This movie was probably how my obsession with the fashion of Old Hollywood started.

There is something so otherworldly about this dress. The way the chiffon almost floats about, the additional liveliness that different shades of blue bring to the dress, creates an astounding effect. For me, Grace Kelly always was and still is a true fashion icon and epitome of elegance. I felt like this dress made her look like a Greek Goddess and who wouldn’t want to look like a Greek Goddess on any given day of the week? Especially now when I’m dressed in comfortable loungewear writing my dissertation, far from displaying any ounce of elegance.

Figures 2: Screen Capture, Grace Kelly in To Catch A Thief (1955)

What is your favourite thing that you’ve written/worked on/researched this year?

Although it was a tough project for me, I loved working on my virtual exhibition. It was such a unique assignment as surprisingly I’ve realised how I don’t think about what goes into the organisation of an exhibition or how difficult it is to choose pieces of artwork to fit into the theme of an exhibition when I visit an exhibition which this assignment made me think about.

My exhibition was on Wiener Werkstatte and Reform Dress of the 1910s. I have first come across this subject when I visited Neue Galerie in New York last summer and saw a few drawings made by different designers of the group. I never would have thought that it would inspire me to write my virtual exhibition on it. However, I was so fascinated by the variety of artistic hand-made objects produced from dresses to the various artworks, illustrations, postcards, and jewellery that these dresses inspired and the lack of any focused exhibitions on this subject made me want to analyse it further. The Werkstatte believed that transforming objects of everyday and thus surrounding oneself with design objects would elevate and transform the mundane reality of everyday life. They named this concept ‘gesamtkunstwerk’ which translated to ‘total artwork’. Although the establishment and growth of the group coincided with both World Wars their success and popularity that stemmed from their constant production of innovative designs saved them from facing an early demise even though the group was experiencing severe economic hardships. It was one of the biggest design movements in history that eventually inspired Bauhaus in Germany. They also further developed the reform dress which was initially established by Gustave Klimt and Emilie Flöge. A baggy dress that completely hid the female figure by eliminating the corset coincided with and was further fuelled by women’s emancipation movements that were taking place around the world. I loved curating this ‘virtual exhibition’ where I got to bring together dresses, fabric samples and various artworks and jewellery that were inspired by these dresses in one space and see how each artist responded to one another, further fuelling this hub of creativity. I loved studying this pivotal period in fashion where the elimination of the corset fashion broke another boundary and entered a new age in the West.

Figure 3: Madame D’Ora, Wiener Werkstatte Dress, c.1920s

Figure 3: Madame D’Ora, Wiener Werkstatte Dress, c.1920s

What is your favourite dress history photograph?

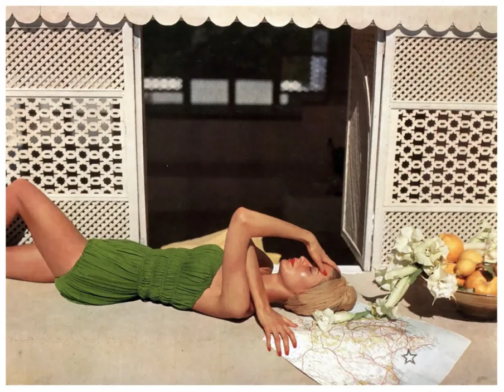

I don’t know whether it’s because I have really enjoyed writing about her for my second essay or because it’s summer (2nd of June as I’m writing this) and I’d rather be sunbathing than cooped up in my bedroom studying, but I adore this photograph from Harper’s Bazaar’s June 1950 issue of Natalie Paine by Louise Dahl-Wolfe and I’m hoping to look as fashionable sunbathing as her in a few weeks’ time. This photograph was from a shoot that Dahl-Wolfe did in Morocco and in true Dahl-Wolfe fashion her impeccable mastery over light and shade and her precise knowledge of colour theory once again shines through this photograph. Dahl-Wolfe often used geometry and divided her photographs into planes and patches of colour to draw attention to the model’s flexible body and the wonders of American sportswear. The patches of colour here from the green bathing suit, the model’s bright red lips and matching nails, to the fruit basket all juxtaposed against a monochrome setting, white moucharaby (a Moorish style enclosed closed balcony with the enclosure made up of carved wooden latticework), beige ground, exactly does that and directs the eye to the model and the horizontal axis of colour that is created with the model and the fruit basket. I was wondering why I was instantly drawn to the gorgeous vibrant green bathing suit and very quickly found out that it was a design by Clare McCardell who I have become obsessed with throughout my studies at Courtauld and was disappointed how little information existed on her and her designs. Dahl-Wolfe and McCardell often collaborated as Dahl-Wolfe found McCardell’s dresses to be incredibly photographable and who wouldn’t agree with that statement as the photograph speaks for itself? I love the clever and unexpected placement of a map with a star placed on it just under Paine’s head, as if she is already planning her next getaway and is ready to hit the road for someplace else any second, which is a mentality that we should have at all times.

Figure 4: Louise Dahl-Wolfe, ‘Afternoon in Moucharaby’, Harper’s Bazaar June 1950

As I was writing this blog and went through the various research that I’ve conducted over the course of a year, I’ve realised how I’m much more conscious of dress and its power of making a statement, constructing an identity and reflecting the spirit and culture of a society. Every day we make a choice of presenting a different version of ourselves to the world around us. Whether it’s a conscious decision or not, it is a silent yet powerful declaration regarding who we are or who we want to be in this world.

By Ipek Birgul Kozanoglu

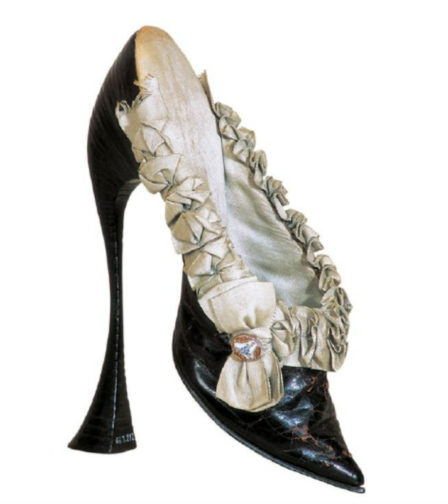

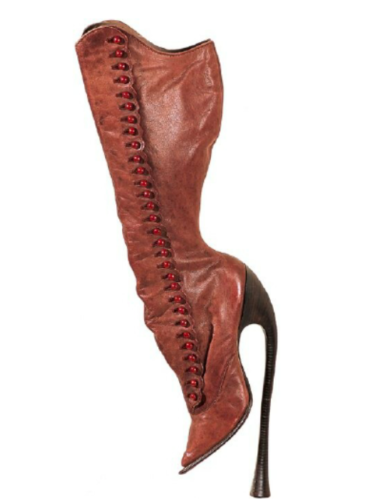

Maddy Plimmer, No Romance on the Pedestal, 2021, Goldsmiths MFA Degree Show, London

Maddy Plimmer, No Romance on the Pedestal, 2021, Goldsmiths MFA Degree Show, London