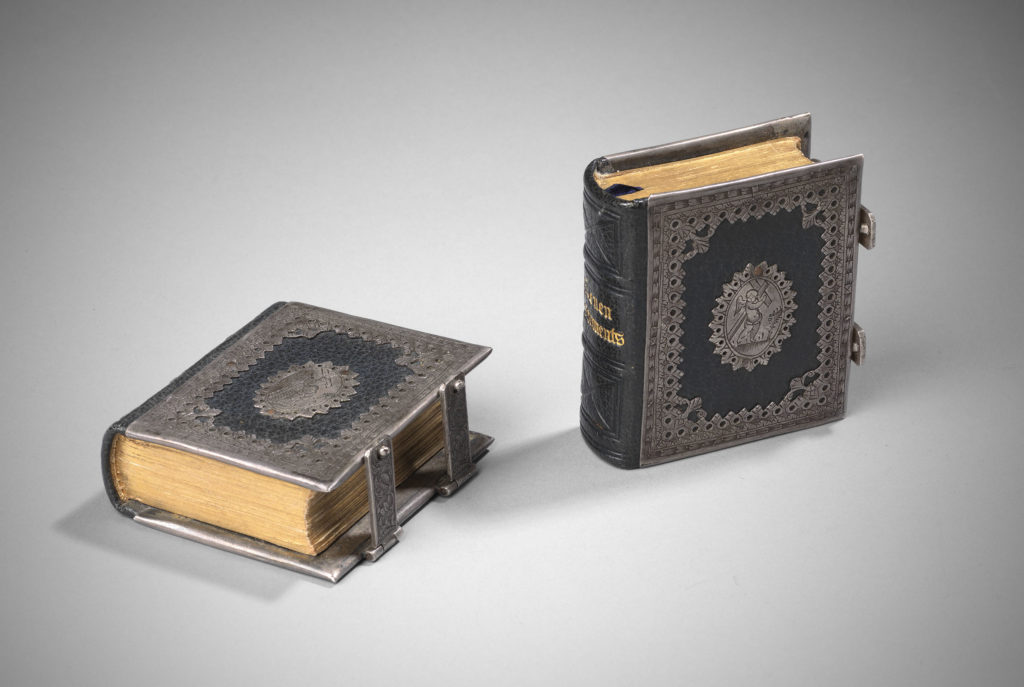

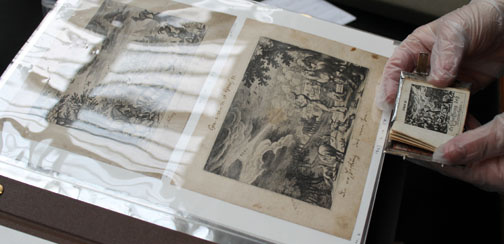

Maria Magdalena Küsel, after Johanna Christina Küsel, Miniature Engraved Picture books of the Old and New Testament, c. 1690, each 5.7 x 5 cm, © The Samuel Courtauld Trust, The Courtauld Gallery, London, O.1966.GP.40.1 and O.1966.GP.40.2

Leafing through The Courtauld Gallery’s German miniature picture Bibles is an enthralling experience. Each measures a tiny 5.7 cm in height and teems with intricate engravings. The books are Split into Old and New Testaments, and were produced by the Küsel sisters from Augsburg in the late seventeenth century. Josephine Neil explores the world of the Küsels and their heritage of master engravers, while teasing out the nuances of a market catering to both Catholic and Protestant ideologies.

Work on this project was carried out by Josephine during her doctorate in Theology and the Arts at King’s College London.

The Küsel Sisters

These Bibles, respectively entitled Dess Alten Testaments Mittler and Dess Neuen Testaments Mittler, were most likely created for use in private devotion. Johanna Christina Küsel (born 1665, active until about 1700) was responsible for the designs and Maria Magdalena (active about 1688–1702), was the engraver. While most seventeenth-century ‘thumb’ Bibles are thought to have been destined for children, the Küsels’ Bible, with its complex and sophisticated engravings, was probably intended as a portable object for private contemplation.

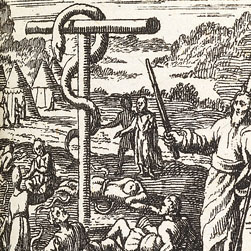

The books were printed without place or date, with only the name of the Küsel sisters present on the title page. Here, the alternative spelling of ‘Kuslin’ is used. We know that the sisters belonged to a family of talented printmakers in Augsburg, and were active during the second half of the seventeenth century. The family workshop likely produced images as illustrations in numerous shapes and forms, adapting and reusing compositions for various purposes and formats. The sisters’ father was the engraver Melchior Küsel (1626–83) and their grandfather was Matthäus Merian the Elder (1593–1650), whose most famous engravings were for a picture Bible published in Frankfurt in 1625, known as the Icones Biblicae. Merian’s engravings dealt in depth with the religious concepts of the time by emphasising the individual’s relationship to God over exterior acts of public worship. The purpose of the Icones, Merian stated in his printed dedication, was ‘not only to amuse, but also, and this pointedly, to enlighten and encourage one’s soul, to trigger reflection of the history involved’. Merian called the Icones ‘a small, comfortable edition of the Holy Bible in hopes that it be not only a feast for the eyes but also be moving and maybe put some fear of God into those that need it’. The Küsel sisters had first-hand knowledge of their grandfather’s prints, basing their engravings on his compositions and adapting them to suit the scale and purpose of their miniature books. The dimensions of the miniature image area are 33 x 35 mm, at most one sixth of the size of Merian’s prints for the Icones Biblicae, which measure 102 x 146 mm inside the platemark.

Making the Bibles

In making their picture books, Christina and Magdalena Küsel compressed the Old and New Testaments into a selection of prints representing episodes from each book of the Bible. The accompanying German captions, probably printed on the page as letterpress in a separate process to the engravings, identify each scene along with the book and chapter of the Bible from which the image derives. There are 132 prints in the Old Testament and 131 prints in the New Testament.

The devotional purpose of the engravings was very compatible with the seventeenth-century predilection for beautifully crafted small objects. The Küsel sisters depicted traditional religious subjects, but in so doing drew attention to their skills as designers of complex engravings. Even if the refinement and craftsmanship of these objects did not captivate the eye, their physical scale alone necessitates close looking. Such delicate and complicated works were not likely produced en masse for children or as instruments of proselytisation. Instead, they would have been destined for an educated elite within Augsburg and beyond.

The devotional purpose of the engravings was very compatible with the seventeenth-century predilection for beautifully crafted small objects. The Küsel sisters depicted traditional religious subjects, but in so doing drew attention to their skills as designers of complex engravings. Even if the refinement and craftsmanship of these objects did not captivate the eye, their physical scale alone necessitates close looking. Such delicate and complicated works were not likely produced en masse for children or as instruments of proselytisation. Instead, they would have been destined for an educated elite within Augsburg and beyond.

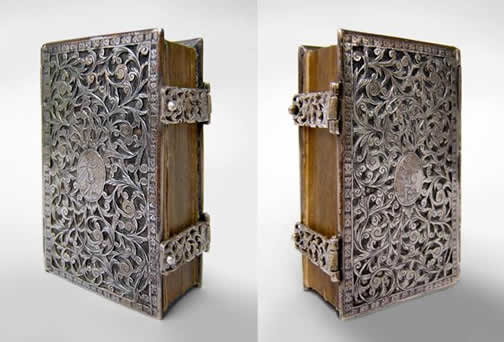

The fine silverwork of the Küsels’ Bibles, including the clasps engraved with a delicate pattern of leaves and flowers, is original to the books. However, the leather binding, interior marbled endpapers and the trimming and gilding of the pages are likely to have been later additions, possibly dating to the Victorian era. The Bibles were acquired in a small town near Nuremberg in 1851 by the collector and artist Thomas Gambier Parry (1816—88). It may be of little surprise that Gambier Parry was a devout Christian.

The order of the pages do not adhere strictly to biblical chronology. For example, in this set the Fall in Genesis III (numbered p. 6) comes before the Creation of Man in Genesis II (numbered p.4), reversing the natural order of the Genesis narratives. Maybe at the time of the Bibles’ restoration, the sheets became inadvertently jumbled. Further research into these books is needed to find out whether this anomaly is a mistake on the part of the binders, or whether there could be another reason for the layout.

The two pairs of oval silver plaques on the covers are curious: they show a putto carrying a cross (recto) and a putto with a basket (verso).

If one examines the putto with the basket very closely, he appears to be holding three nails in his left hand. The putto in the other circular medallion is carrying the Cross. Together, they are symbolic of Christ’s Passion. Nails and other tools of the Crucifixion held by angels are common motifs in representations of the Passion.

This exact choice of iconography is present on at least two further miniature bindings with similar silverwork medallions. One of the books is a morning and evening prayerbook to be used at church or at home, published by Christoph Endter (1632–74) of Nuremberg, in 1672. The size of the binding is comparable, at 7.5 cm high. The prayerbook is dedicated to a high-ranking family from Augsburg. The other example, also printed by Endter in Nuremberg, is from 1668 and housed at the Bamberg State Library.

Reformation and Private Devotion in Augsburg

An increasing emphasis on private devotion and personal piety in German speaking countries during the seventeenth century created an environment favourable for images on paper. The market for engraved biblical cycles as well manuscripts flourished accordingly. As stress was laid on individual piety as a way of drawing Christians closer to God, the demand for books and images to use in the home became pressing across the social spectrum.

Artists, firmly situated in the middle classes in Augsburg, had to work with the religious constraints imposed by the Reformation. The theological context of the miniature picture Bibles stems from Luther’s teaching. Although his death occurred in 1546, his influence remained prevalent in the Augsburg of the late seventeenth century.

Miniature personal prayer books were the accoutrements of fashionable circles in Catholic countries too, as seen in the example of Peter Paul Rubens’s (1577–1640) splendid portrait drawing from The Courtauld’s collection. It depicts his young wife, Helena Fourment (1614–73), dressed sumptuously as though she were about to step out. Most importantly, Helena holds what appears to be a miniature prayer book in her hand.

In Protestant personal devotion, viewers were encouraged to use the printed image within the context of ‘self-reformation’. The image and text together formed a meditative programme that expressed sacred truths. The reader was invited to contemplate and engage with each page, for the purpose of conforming the soul to the Divine will. Imagery was therefore an aid in gauging the soul’s proximity to the Divine and a prompt for enhancing that relationship.

Judgement, Sin and Redemption: Lutheran leanings in the Küsels’ Images

God Have Mercy On Me, Sinner That I Am (Martin Luther)

Man is predestined to sin. The men and women of the Old Testament were not saints to be worshipped and revered. Luther insisted on their human failings and their need for forgiveness from God. If these figures were to be protected and sustained by God, they would need strength of faith and the will of the Lord behind them. Thus, the stories of the Old Testament became manifestations of Luther’s doctrine of salvation not through good acts, but through faith alone: sola fide. There is nothing heroic in the Küsels’ treatment of the Old Testament figures. Images of murder, grief and sorrow abound. Some striking examples can be seen below.

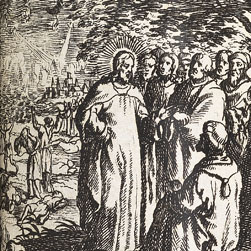

In the New Testament, Christ as the Saviour of the World (Salvator Mundi) features large. The first plate introduces this essential concept, showing the triumphant Christ after his exemplary faith and sacrifice; the redeemer of mankind. In contrast to the Fall of Adam shown in the Old Testament, the figure of the Saviour represents victory over sin, death and hell, and how faith alone breaks the chains of sin, in accordance with Luther’s theology. Trees are common to these two stories. The Old Testament Fall acts almost as a kind of premonition, known as a prefiguration, for the New Testament. With Adam and Eve, the apple is sinfully plucked from the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil, which shares a place in Eden with the Tree of Life. Christ’s cross can be interpreted as an echo of the Tree of Life, with both connected to the absolution of sin.

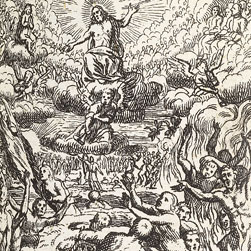

Divine Judgment and Salvation

Divine judgment and salvation are emphasised in many of the Küsels’ prints, as in Matthew XXIV and XXV. For the portrayal of Matthew XXIV, Christ’s prophecy about the destruction of the Temple at the end of days is brought viscerally close to home for the reader. The wrath of the Divine, shown in the background, falls not on an ancient monument but what appears to be a modern cityscape, reminiscent of a city such as Augsburg. In addition, strong emphasis is placed on the torment of the damned in Matthew XXV, to remind readers of the ever-present dangers of falling into sin.

Prominence is also given to selected episodes from the Acts of the Apostles, detailing the conversion of Paul, the coming of the Holy Spirit and the Apostles’ mission, as well as apocalyptic scenes from the Book of Revelation. As well as drawing out the distinction between the Law of Moses and the Gospel, the Old Testament is also illustrated as foreshadowing events in the New. For example, the vision prophesied by Micah that the Messiah would be born in the town of Bethlehem, is envisaged by the Küsels as Christ’s Nativity.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Mr van Noordwijk for generously sharing his vast knowledge on miniature religious books, and for supplying information on comparable bindings to those on our miniature Bibles.