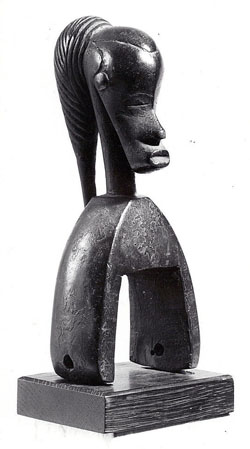

Niamh Collard introduces us to a delicately carved loom pulley from The Courtauld Gallery’s small collection of African sculpture. Used in textile weaving, the pulley was made by the Guro people of Côte d’Ivoire in West Africa in the late 19th or early 20th century.

Niamh researched this object during her PhD in Anthropology at the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. This topic is close to her heart, owing to her doctoral work on the educational and working lives of narrow-strip weavers in eastern Ghana, and having spent a year in the field during which she apprenticed as a weaver.

The Guro

Guro-speaking people hail from the central belt of Côte d’Ivoire, their land stretching along the western shores of Lac de Kossou. Historically the Guro were seasonal farmers and hunters. Men would take up the work of weaving and carving during the dry season, which runs from December through to April. The Guro language is of Mande origin, a large group of languages spoken across the western part of West Africa.

The Guro people migrated from Mali and settled in the central belt of Côte D’Ivoire between the 13th and 16th centuries, inhabiting something of a crossroads in West Africa. They are bordered by the forested equatorial coast to the south, with its long history of maritime trade. To the north is the Sahel and the Saharan desert with its own history of Islamic trade routes.

Extensive interaction with neighbours to the east has also been important, placing the Guro people at the heart of a complex history of migration, trade and war which has shaped not only their artistic traditions, but also those of their neighbours and that of the region more widely.

The Guro and the Dioula: Two Mande Speaking Peoples

Moving southwards from Mali, the Guro brought with them their language, which belongs to the much larger family of Mande languages widely spoken across the western part of West Africa. The link with the north was maintained by constant interaction with another people, the nomadic Dioula, who were well known as traders and weavers.

The Dioula traded in cloth, metal and salt, and it is likely that some weavers settled in Guro areas. This interaction with the Dioula formed an important connection with the northern hinterland, which is the heartland of the Mande–speaking people.

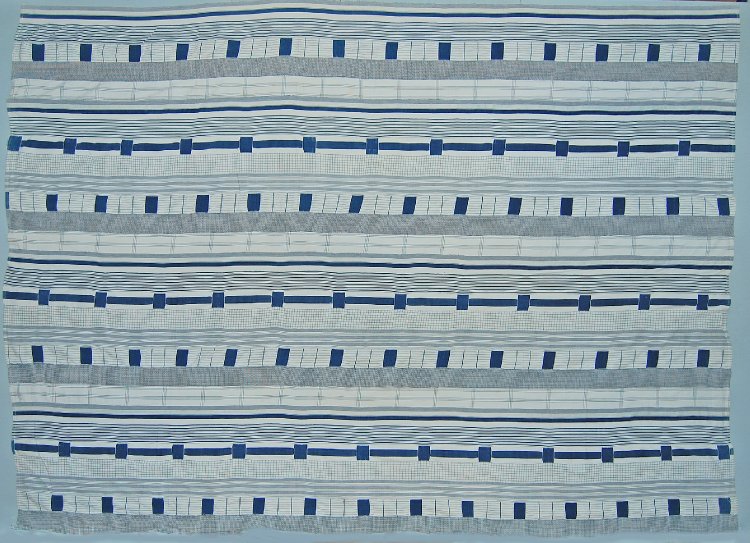

With Dioula weavers moving from village to village, it is possible that they may have introduced the craft to this part of West Africa. The 20th-century Dioula cloth shown below features indigo and white geometric patterning that bears a resemblance to Guro weaving of the same period.

Eastern Contacts: Baule and Asante Peoples

Today the Guro’s neighbours to the east are the Baule and the Asante, who both speak languages of Akan origin. The militarised expansion of Akan-speaking people from what is now Ghana in the 17th century halted the movement of the Guro eastwards. These Akan migrants settled along the eastern shores of the Lac de Kossou, assimilating to form the Baule. A subsequent history of trade in the cloth between Guro people and their Baule neighbours has resulted in not only ethnic but also cultural ties linking both groups.

Although Baule weaving is more renowned than Guro weaving today, it is thought that the Guro taught their neighbours, the Baule, to weave. Historically, both groups have also produced decorated loom pulleys featuring human and animal figures, with Asante people who neighbour the Baule to the east in Ghana also having a vibrant history of loom carving and weaving.

Female Beauty

Female heads are a common subject of carved loom pulleys. The Courtauld’s example has the elaborate hairstyle, scarifications, downcast eyes and open mouth typical of Guro ideals of feminine beauty. At the turn of the 20th century, West African sculpture became popular with European avant garde artists, collectors and critics. The Courtauld’s modest collection of African objects was bequeathed by modern art critic Roger Fry (1866–1934). Valued for their sophisticated and abstracted interpretation of the human form, West African objects had a significant influence on the development of modern art. Modigliani (1884–1920), whose painting, Female Nude, of 1916 is on display nearby, was directly inspired by the aesthetics of the Baule people of Côte d’Ivoire, neighbours of the Guro.

Weaving and Wearing: A Male Dominated Craft

A beautifully carved tool, The Courtauld’s pulley would have been an essential tool in the loom of a Guro weaver. It would be hung from the upper struts of the loom as a means of suspending the heddles that control the opening and closing of the warp threads. And thus, the object is also known as a heddle pulley. The loom itself can be built directly into the ground or carpentered so that it is portable. Amongst the Guro, as in most of West Africa, weaving has historically been and largely remains a gendered form of work. Undertaken by the men in a family, boys learn from their fathers, uncles or older brothers and women are prohibited from practising the craft. Having mastered the necessary techniques, a young man would, in turn, pass these skills onto his own sons, nephews or younger brothers. Depicting an idealised female face, the pulley would have hung intimately close to the craftsman’s face, allowing him to reflect on something beautiful while he worked. Guro weaver Boti bi Yuan, shown at his loom here, said in an interview of 1984 “When you work it is very pleasant to see something nice in front of you.”

Designing Guro Clothes

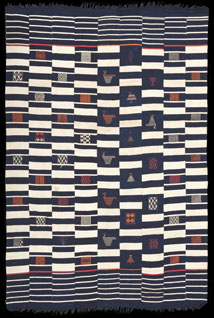

Guro woven textiles are part of a broader West African tradition of cloth production, in which narrow strips measuring between 1 and 45 centimetres are stitched together to produce larger cloths.

Each individual strip often features a number of patterns that are either geometric or figurative. Thoughtfully arranged and sewn together, these narrow strip textiles offer an extraordinary range of possible visual effects. Designs show innumerable regional and stylistic variations, as well as reflecting the personal taste of the individual weaver and patron.

Historically Guro cloths would have been most commonly executed using white, indigo and red cotton, produced and dyed locally. The increasing availability of synthetic dyes and commercially produced cotton and acrylic yarns since the middle of the 20th century have allowed for a much wider spectrum of colours to be incorporated.

Valuable Cloth

In the past, Guro textiles would have been principally used as clothing, with everyday clothes made from plain textiles and intricately woven prestige pieces kept for festivals or other special occasions. Today their use during special occasions predominates. Woven textiles also form part of a woman’s dowry and are used in funerary rites to wrap the body, place in the tomb and as gifts to the family of the deceased. Masquerade costumes are often made from woven textiles. Textiles also play a role in dispute resolution, when gifts of cloth may be presented as a gesture of reconciliation from one party to another. Despite changes in the status of weavers throughout the 20th century, Guro textiles have retained their value as an item of local and long distance trade.

Masquerade

The Courtauld’s loom pulley most likely represents a specific type of entertainment mask, but in miniature form. Looking at the loom pulley from an anthropological perspective can inform us about Guro masquerade traditions.

This object is clearly linked to several interesting processes of material, spiritual, and physical transformation. As across much of West Africa, Guro wood carving is a male-dominated and specialised form of craftwork.

The Guro people of Côte d’Ivoire have a number of masquerade traditions, performed for both entertainment and religious purposes. The type of mask to which the loom pulley relates was made for the Sauli entertainment masquerade, which is danced in commemoration of a beautiful woman. Master carvers produce the wooden masks used in these performances and it is likely that in the past these same craftsmen also made carved loom pulleys. Like The Courtauld’s loom pulley, this mask, dating from the mid-1970s, depicts a woman’s head surmounted by a chameleon.

Today Guro master carvers mainly focus their attentions on the wooden head masks used in performance. In the past they also used their skills to carve decorative loom pulleys and spoons.

Carving masculinities

Carving is distinct from the everyday occupations of farming and hunting. Guro carvers work away from their village homes at secluded, sacred spots in the nearby bush where they won’t be disturbed by women or children. Working in the forest, the carvers harness the power of the bush to transform the material into intricately carved masks. Craftsmen fell the trees they need for carving. The process of carving, staining and painting objects is often several days’ work and imbues carvings with the power of the forest. Such is the power that, outside of performances, women and children are not allowed to touch or see masks.

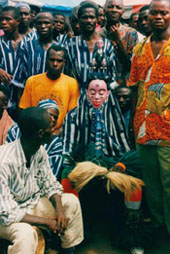

Masks are exclusively worn by men to dance a range of different types of masquerades — some are purely for entertainment, while others are religious. Guro head masks are combined with hand-woven cloths to create colourful costumes that cover and disguise performers. When worn by a skilled dancer these costumes are part of the spiritual and corporeal transformation of the performer. Upon donning the costume, a performer’s everyday identity is eclipsed and he comes to embody the spirit of the masquerade.

This vitality is reflected in the Guro language which defines a masquerade as a complete living entity comprised of spirit, costume and performance. Religious masquerades are believed to be particularly powerful and pose a danger to women, who are forbidden from attending these performances. Women can, however, watch entertainment masquerades, such as the Sauli masquerade upon which The Courtauld’s loom pulley is based.

From the carver’s sacred grove to the masquerader’s performance, Guro carving and masking are male domains where gendered power is involved in a series of intimate transformations. These processes of transformation are both material and spiritual, hewing beautiful objects from wood and metamorphosing men into powerful masqueraders.

References and Further Reading

Further Reading

Adams, Monni. ‘Review: Masks in Guro Culture by Eberhard Fischer; Lorenz Homberger’. African Arts, Vol. 20, No.1 (November, 1986): 21–22.

Bauer, Kerstin. ‘Côte D’Ivoire: Textile Craft Between Success and Decline’. In Woven Beauty: The Art of West African Textiles, edited by Bernhard Gardi, 135–51. Basel: Christoph Merian, 2009.

Bouttiaux, Anne-Marie, and Allen F. Roberts. ‘Guro Masked Performers: Sculpted Bodies Serving Spirits and People’. African Arts, Vol. 42, No.2. (Summer, 2009): 56–67.

Etienne, Mona. ‘Women and Men, Cloth and Colonization: The Transformation of Production-Distribution Relations among the Baule (Ivory Coast)’. Cahiers d’Études Africaines, Vol. 17, Cahier 65 (1977): 41–64.

Fagg, William. Miniature Wood Carvings of Africa. Bath: Adams & Dart, 1970.

Farr, D. Francine. ‘West African Heddle Pulleys’. African Arts, Vol. 13, No. 2 (February, 1980): 74–75.

Fischer, Eberhard. Guro: Masks, Performances and Master Carvers in Ivory Coast. Munich: Prestel, 2008.

Picton, John, and John Mack. African Textiles. London: British Museum Publications, 1989.

Schaedler, Karl-Ferdinand. Weaving in Africa South of the Sahara. Munich: Panterra Verlag, 1987.

Spencer, Anne M. ‘Art of the Guro, Ivory Coast’. African Arts, Vol. 19, No. 3 (May, 1986): 92–93.

Sumberg, Barbara. A History of Cloth Production and Use in the Gouro Region of Côte d’Ivoire. Ph.D diss.; University of Minnesota, 2001.