Maddy Plimmer, No Romance on the Pedestal, 2021, Goldsmiths MFA Degree Show, London

Maddy Plimmer, No Romance on the Pedestal, 2021, Goldsmiths MFA Degree Show, London

On a recent visit to the ‘London Grads Now’ exhibition at the Saatchi Gallery, showcasing the works of recent art school graduates, I was magnetised towards a towering pair of heels (above). Created by Goldsmiths graduate Maddy Plimmer, these heels, at a metre tall, are not for the faint-hearted or weak-ankled. Plimmer explains that the inspiration behind these art objects was a mobile game featuring a female avatar whose heels grow in height as she navigates a progressively challenging obstacle course. The precariousness of women’s existence through self-elevation, literal or metaphorical, is evidently a topic of fascination. I couldn’t help but imagine how painful the experience of standing, let alone attempting to walk, in these shoes would be.

The obsession with shoe-related female discomfort is by no means a new concept. Footbinding, a practice enforcing the beauty standard of delicately small feet, is a global phenomenon throughout dress history. Not only did binding stunt foot growth, it also debilitated women’s ability to stand, walk and exist. The historic desirability of women’s tiny feet and dainty little shoes makes the female foot an eroticised object that warrants regulation. For example in China during the Ming dynasty, if a woman revealed a barefoot in public, she would be committing an indecent assault. The air of secrecy that feet acquired through centuries of being hidden away is what made them so controversial. Shoes, hinting at what lies within, have thus become objects of Freudian fetish fascination.

Foot reliquary of Saint Blaise, c. 1260, Musée provincial des Arts anciens, Belgium

In its purest form, ‘fetish’ defines objects that have religious or spiritual significance, such as reliquaries. Saint Blaise, a fourth-century physician and healer, was beheaded for refusing to renounce his Christian faith. The above reliquary, supposedly containing authentic relics of his foot bones, served a practical function of directing prayer, as well as embodying and inspiring fervent Christian dedication. Comprised of oak, stone and precious metals, each individually crafted toe hints at the holy bones contained within without revealing them. However, the hinged door detail implies that the reliquary could be opened to witness the relics.

From a dress historical point of view, the reliquary calls to mind Maison Margiela’s iconic Tabi boot (below). Like the medieval reliquary, the Tabi draws attention to the separation of the toes, connoting the foot within without directly showing it. The almost hoof-like appearance of the foot takes on a fetish significance, but not in religious terms. The statement shoe draws the eye down the length of the body to be affronted by a yonic slit in the usual place of a modestly covered foot. While heels are usually regarded as phallic objects to elongate and accentuate the sexualised female form, the Tabi boot subverts this, and is particularly potent when worn by a man.

Maison Margiela, Mens Painted Calfskin Tabi Boots. maisonmargiela.com

Appropriated from Japanese tabi that date back to the fifteenth century, Margiela’s boot continues a long history of the regulation of women through their footwear. Tabi were originally leather shoes made from a single piece of animal skin, later evolving into split-toe socks to be worn with thong shoes, such as geta.

Koma geta, second half on 19th century / Edo period, Japan, Tokyo, Musée de Quai Branley, Paris

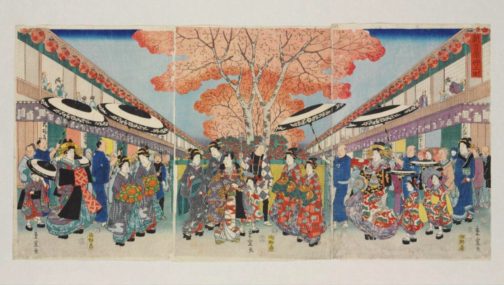

This pair of geta, nearly 30 centimetres high and weighing over 2.5 kilograms, belonged to a courtesan in the Yoshiwara pleasure district of Edo, modern-day Tokyo. The two wooden ‘teeth’ platforms are ornately decorated in guided floral motifs, whilst the straps are wrapped in now faded velvet. Both connote a degree of luxury, suggesting the status of the courtesan. The woodblock print below depicts a procession of richly-dressed courtesans, all in geta and ornate kimonos, accompanied by attendants. However, this is not an accurate depiction of the realities of the sex district. By physically elevating the female wearer, geta were utilised as a way of identifying courtesans within the district, especially to make sure they weren’t running away. Furthermore, some geta also bore the mark of the courtesan’s owner, revealing that these shoes were a way of binding courtesans to their life within the sex district, thus denying female empowerment or freedom.

Utagawa Hiroshige II, Nakano Street in Yoshiawa district in Edo, 1857, woodblock print, Japan, V&A, London

Restrictive footwear, in every sense of the word, is also evidenced throughout Europe. For example, chopines were highly popular throughout Renaissance Europe, in particular Venice. These stilt-like shoes served the practical function of elevating the wearer above flooded streets to prevent their expensive garments from being dirtied. However the chopines below, at around a staggering 55 centimetres tall, offer an entirely impractical degree of elevation.

Chopine, Italy, circa 1600. wood and leather. Royal Armoury, Stockholm

This suggests that chopines also served the symbolic function of displaying status, as they literally showcased women of higher standing. Additionally, chopines create a phallic image of the female form – transforming her into an erect column-like structure. According to Freud, it is not simply the fact that the shoe imitates the form of a phallus that justifies fetishists’ appreciation of footwear. It is also the positioning of the shoe in relation to the body, creating a link up to the leg towards the genitals. Freud argues that young boys, from their low vantage point, make this link in relation to their mother and their mother’s absent penis. The materials of heavy skirts that shield the female body from prying eyes add an erotic level of mystery to this.

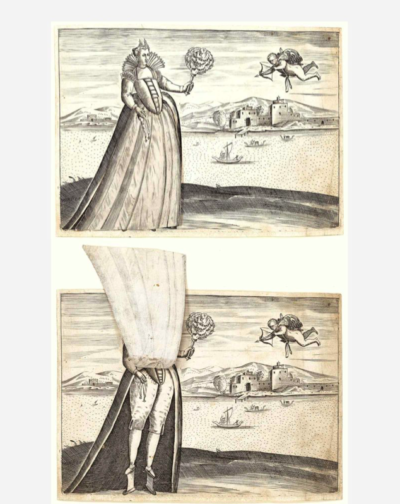

Ferrando Bertelli, Venetian Woman with Moveable Skirt (with flap lifted to reveal her chopines), 1563. Engraving, 14 x 18.9 cm. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The above image depicts a respectable sixteenth-century woman who is reduced to ridicule as her skirt can be lifted up to expose her chopines as well as her breeches. At the time, breeches, a masculine undergarment, were often adopted by prostitutes. The hovering cupid, once her skirt is lifted, crudely points his arrow directly at her covered genitals. Her chopines are not as grand as other examples. She is neither elevated through her rank nor her footwear, making her lowered status as a prostitute a possibility.

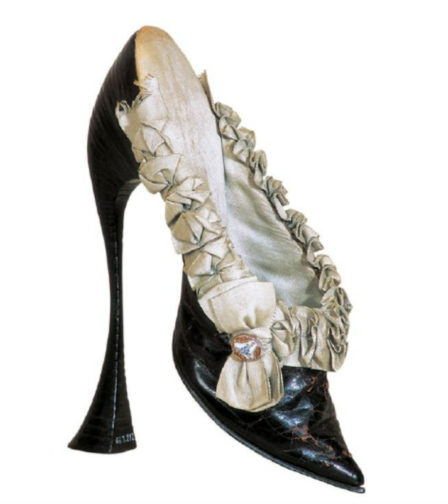

Mule, circa 1900, Vienna, Austria, International Shoe Museum, Romans.

Excessive heel height is not only about displaying women’s aspirational status but also about diminishing and controlling them through severe discomfort. The above fetish mule, made of black kidskin, represents female discomfort for male gratification. The severe point of the toes, combined with the flared and precariously narrow 20-centimetre heel, reveal that it would be impossible to stand in these delicate shoes. They could only be worn sitting or lying down. Yet these mules would have enhanced the curvature of the arch of the foot to an extreme degree, creating a graceful silhouette. The intricate ruffled detail and the bow adorned with a cabochon set in porcelain demonstrate that this is a valuable object. Hence, this shoe is not about diminishing a woman’s social standing, but about reducing her to an immobile, passive object of desire.

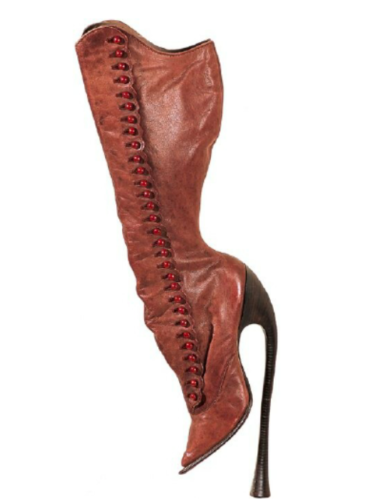

Fetish boots, c. 1900, Vienna, Austria, International Shoe Museum, Romans

Similarly, the 28-centimetre heel of the above fetish boot creates an unnatural curvature of the female foot. The point of the shoe and the heel sit at different heights, again showing that these boots were not made for walking. The length of the boot, extending up the entire calf, evokes the physical proximity of the leather to the female skin, which adds a layer of fetishism to the object. The thirty two intricate button fastenings up the length of the boot enhance this, creating a sense of longing for what the boot encapsulates but is unwilling to surrender. In this way, it is not entirely dissimilar to the foot reliquary.

Christian Louboutin, Pumps, 2007, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Louboutin’s 2007 ‘Fetish’ collection brings the themes of early twentieth-century fetishism into the present day. Louboutin takes the humble flat ballet pump, a staple of contemporary women’s wardrobes, and morphs it into something that looks like an instrument of torture. In the campaign shoot, photographer David Lynch stressed this element of eroticised female suffering.

David Lynch, Fetish, 2007. Courtesy of Christian Louboutin

In keeping with the ballet pump, Lynch requested dancers instead of models for the shoot. This also tied in with Louboutin’s origins as a shoe designer for showgirls at the infamous Paris cabaret music hall, the Folies Bergère. Thus dance and movement (or a lack of movement) have always been taken into consideration in his designs. Moreover, Louboutin prioritises his imagination over technical elements and natural proportions, and this is certainly the case here. The strong, athletic legs of the dancer tower over her tiny delicate feet that are hardly visible in their contortion. The harsh light projects a shadow of the extreme, sensuous curvature of the dancer’s feet, teetering precariously en pointe. Lynch has created an atmosphere shrouded in secrecy through these chiaroscuro light effects, forcing the viewer into the role of the voyeur. The dancer’s naked body is fragmented as we can only see her bare legs. Her arms are out of shot and supposedly holding onto supports. The blurred image evokes a sense of panicked movement, as if she is in the process of falling. In this instance, it is the delicate vulnerability of a woman wearing such torturous shoes that renders her an object of spectacle and thus of erotic fascination.

There is something inherently powerful about employing footwear, something that was originally designed to root you to the ground and facilitate walking, as a means of self-elevation through tolerated agony. Yet if such an accessory is forced onto unwilling feet, it denies selfhood, and objectifies the wearer as a passive mannequin-like static form.

By Claudia Stanley

Sources:

Apter, Emily. Feminizing the Fetish : Psychoanalysis and Narrative Obsession in Turn-of-the Century France. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2018.

Bossan, Marie-Josèphe. The Art of the Shoe. New York: Parkstone, 2004.

Croizat-Glazer, Yassana. Historical Shoe Trends, Sexual Contrasts and the Need to Take Up Space. 15th July 2021: https://awomensthing.org/blog/historical-shoe-trends-chopines-crakows/

Furiassi, Cristiano Gino. Chronicling a Global Fetish: A Linguistic Analysis of the Pseudo-Italian Internationalism Stiletto. ZoneModa Journal 9, no. 2, 2019. pp. 103–121.

Hamlyn, Anne, Freud, Fabric, Fetish, Textile: The Journal of Cloth and Culture, vol.1, no. 1, March 2003. pp. 8-26.

Jacobs, Fredrika H. Shoes. Res (Cambridge, Mass.) 71-72, no. 1, 2019. pp. 284–294.

Jacques M. Chevalier. “Foot and Shoe Fetishes: The Bright Side.” In Corpus and the Cortex, 109–. MQUP, 2002.

Stephens, Sonya. Sex and Spleen: Fetish in Baudelaire’s ‘les Bijoux.’ South Central review 29, no. 3, 2012. pp. 63–79.

V&A. Christian Louboutin interview, 2015: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WrH4JlyW5zo