We’ve been busy working on our dissertations, so we’re taking the opportunity to get to know the current MA Documenting Fashion students. Here Victoria discusses Celtic Revival craftsmanship, the humble sundress and her fondest fashion memories.

What is your Dissertation about?

My dissertation centres around a study of the Celtic Revival period in Ireland. Through a close analysis of two defining cultural leaders of the era- The Dun Emer Guild of craftswomen and the Anglo-Irish patroness Lady Aberdeen, I’m looking to place in context the ethnic fashions of an emerging nation which must first come to terms with its troubled past.

I first learned about the Dun Emer Guild during my undergraduate degree in Dublin. As an Irish woman fascinated by fashion and textile history I was shocked to have never been introduced to the story of this revolutionary institution before, and knew that I couldn’t be the only one missing out. From there an obsession took root, which eventually inspired my dissertation topic.

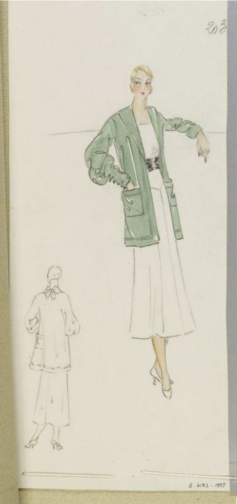

This subject area feeds into my particular interest in artisanship and the handmade. Truly, as much as I adore leafing through old editions of Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar, it has been an indescribable pleasure to dive head-first into a pseudo-archaeological study of fashion history. I have had the opportunity to physically explore and examine some of the most exquisite creations from this period in history, and have had the chance to understand them as lived creations. One of my favourite encounters I have had on this research journey has been with a watercolour sketch of a Celtic Revival outfit by craftswoman Katherine ‘Kitty’ McCormack of the Dun Emer Guild (figure two). The juxtaposition of an overtly 1920’s drop waist silhouette alongside an attempt to reproduce key garments of the traditional Celtic wardrobe such as the léine (tunic), brat (sash) and ceannbheart (headdress) delighted me no end upon first discovery. This fusion of heritage and Modernity encapsulates the spirit of the Celtic Revival which I am attempting to address in my dissertation, and is epitomized by this sketch.

Which outfit from dress history do you wish you could wear?

As of late, I cannot stop thinking about Marilyn Monroe’s blue polka-dot sundress from 1957. Ever the pragmatist, I couldn’t justify naming a fanciful suit of armour or extravagant ballgown as my answer for this question, as I am inferring (or rather deciding) that I get to keep whichever garment I choose. Yet, I know if I could ever lay my hands on this dress I am certain I would probably never take it off.

This outfit epitomizes exactly how I aspire to dress in the summer. Maybe it’s just the idyllic outdoor scene created in this photograph, but Marilyn in this dress looks the image of peace, comfort and class. I love the timelessness of its design, and the serene subtlety of the baby blue fabric against her wispy blonde hair. As a blonde myself, the discovery of this photograph a number of years ago began a painstaking search for a similar outfit. Resultingly, I fell down a rabbit hole of light blue 50’s style dresses which led me to the discovery of Kate Moss’ “Breakfast at Dior” shoot for Glamour France in 1992.

In this Gianni Versace taffeta ensemble Moss embodies the mid-century American Barbie in an almost Stepford Wife-esque eeriness. Whilst obviously dissimilar to Marilyn’s sundress, both outfits take their inspiration from the classic 1950’s swing dress silhouette. The simple twinning of this design with the baby blue colour activates a ravenous part of my brain which deems it a necessity for me to have one of these outfits. Or preferably both.

What are you wearing today?

Shockingly, the onset of summer has meant that London has gotten very warm all of a sudden. With that in mind, today I am wearing a vintage pink cotton sundress which I picked up from a young woman on eBay who was looking to find loving homes for her grandmothers clothes from the 1940’s, 50’s and 60’s. The dress is very clearly handmade and was fitted to the exact specifications of the wearer. Luckily enough for me they seem to be my precise measurements too, as this dress feels like a second skin when worn. On my feet I’m wearing a pair of beige espadrilles with rope lace ties to my ankles. I swear they look less odd than they sound. Finally, in my handbag I have a cream cable knit cashmere cardigan which may or may not be donned in this humidity. I have owned this cardigan for as long as I can remember, an thusly cannot recall where I picked it up.

Practically, the summer season is probably my least favourite to dress for. If you have ever met me you will understand the remarkable paleness of my unmistakably Celtic skin. To be frank, I am translucent. Thus, I must always factor in the copious amounts of sun cream I have to wear in order to reveal any skin during these months. Simple sundresses like the one I’m wearing today allow me to navigate this tricky balancing act as easily as possible, and enable me to somewhat mitigate the amount of time I have to spend vampirically skulking indoors. Being permanently alabaster in a climate which regularly has the gall to rise above 22 degrees is far from ideal, yet I find classic pieces such as this dress incredibly effective at minimising the hassle of the season.

Do you have an early fashion memory to share?

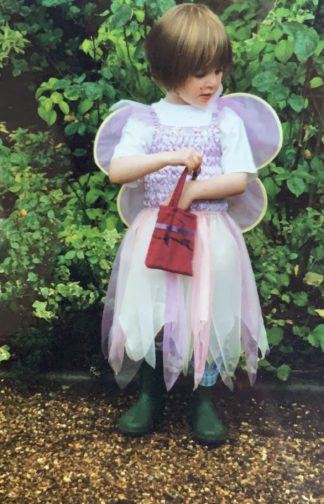

Whilst considering this question I have recalled a number of memorable fashion moments from my childhood, yet one common denominator prevails amongst all of them. I think it is only right that I answer this question by way of lauding my greatest fashion inspiration, teacher and supporter – my mother Paula.

Some of my earliest memories of experiencing fashion with my mother involved her teaching me to touch textiles before I even considered their aesthetic appeal. Learning the difference between your cottons and linens, your synthetics and your organics and your tweeds from your tartans formed the basis of my early relationship to clothing, and is responsible for my passion of exploring skilled textile craftsmanship. To this day I cannot sleep on a polycotton bedsheet, and can’t stand the sticky cling of a synthetic sports jersey. I have all of these little textile quirks to thank my mother for.

Probably the most singularly influential moment in my early relationship to fashion are my memories of the creation of my Communion dress. As to be expected with Paula FitzGerald, an off-the-rack white dress would not do for her daughter, so she enlisted the services of the same seamstress who created her wedding dress to construct my special outfit. At just eight years old I vividly remember going to dress fittings with my mother who had a detailed design for the whole ensemble. Day trips were spent going to Dublin haberdasheries, where ribbons and lace were studied and deliberated by my mammy. The finished white cotton dress was her most beautiful brainchild, and was gracefully unique and understated. Through that experience I began to understand clothing as something inherently tied to the human experience, and not simply as an inconsequential consumer item.

As I am answering this question I have come to realise that I probably have another dissertation’s worth of memories that I could recount regarding myself, my mother and fashion. The experiences I have shared with her throughout my life have been the single most influential force on my studies of fashion at the Courtauld, and continue to guide my relationship to clothing every day.

By Victoria Fitzgerald