Truthfully, Eurovision has always appealed more to my mother and one of my brothers than it has me. Although, I think this is perhaps partly to do with my mother’s near-obsessive determination to learn (or at least be able to mumble, sorry Mummy) each entry’s chorus before the *big* day, which was an annual occurrence in our household. Or was it the twenty-minute blind panic – yes really! – when the box filled with feather boas and sequin ensembles in red, blue, and white would go ‘missing’…despite being kept in the same spot in the same cupboard for over a decade.

In fact, Eurovision has held more of a significant place in our family than anyone’s birthday or Christmas for as long as I can remember. In reality this meant that for at least two months of every year, the Eurovision CD would be the only music which we’d listen to (forcefully or otherwise), and is undoubtedly the reason as to why we still have our trusty twenty-year-old Sony CD player, which continues to take pride of place in our kitchen at home in Edinburgh. And I suppose it also explains why I still have a soft spot for the United Kingdom’s 2007 entry ‘Flying The Flag’ by Scooch and can still remember at least 90% of the lyrics. No word of a lie.

Eurovision is also how my mother remembers my due date, as it coincided with the date of the Eurovision Song Contest back in 1999. Had I been born that day I’m certain of the fact that I would have at least ended up with the winner’s first name as a middle-name – Charlotte Nilsson who won on behalf of Sweden with ‘Take Me To Your Heaven’.

As such, I think it’s only right that we should be looking my top five favourite Eurovision fashion moments ahead of its 66th competition. Even if Eurovision isn’t for everyone, it’s a wonderful excuse to inject a bit of sparkle into any wardrobe and a time to be grateful for autotune (just kidding, or at least sort of).

FIVE: JACQUELINE BOYER (1960)

This below-the-knee cowl-necked dress worn by Jacqueline Boyer is at once subtle and eye-catching. The billowing skirt, complete with four frontal pleats work to accentuate the waist and the tutu fabric hidden from view helps the skirt retain its shape. Although relatively simple in design, the piping featured at the bottom of the dress and at the neckline help offer a chic touch.

Last to perform on the evening, Boyer’s Tom Pillibi at the Eurovision Song Contest in 1960, marked the first time that the winning song had closed the competition. Quite the feat aged just eighteen! Moreover, her father Jacques Pills had performed at the Eurovision Song Contest in 1959, as Monaco’s first representative, but his performance didn’t fare so well, and he placed last, a rather less enviable position…

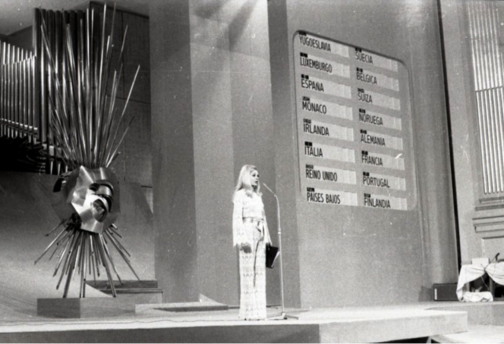

FOUR: LAURA VALENZUELA (1969)

This next look was worn by Spanish TV presenter Laura Valenzuela for the 1969 Eurovision Song Contest. The high neck lace suit is chic as it is sophisticated, sexy yet understated. The high neck and long scalloped sleeves help ground the sheer fabric and the suit is tied together with a beige belt which looks to be made out of satin. The script and microphone for the evening form the host’s ‘accessories’ and a page is clearly earmarked for easy access. This lace jumpsuit recalls RTW S/S 20, specifically Look 19 at the Alexander McQueen show, which similarly features long frilled sleeves, a high neck and is tied together with a contrasting belt.

THREE: ABBA (1974)

Of course, it wouldn’t be a Eurovision round-up without featuring the sensation that is ABBA. They graced us with their Eurovision presence in 1974, with their now-classic, karaoke or silent disco must-have song Waterloo, claiming the first-place prize – rightfully – as their own, despite the United Kingdom offering the song a scathing nul points back in 1974.

With icons come iconic looks and these outfits scream seventies. Metallic knee-high platform boots (a win!) are paired with tops which look like they’ve been attacked with a glue gun and are covered in glittery stars and diamanté studs, making it an easy fancy dress outfit to recreate. Just don’t get me started on Agnetha Fältskog’s lapis blue beanie…

TWO: SCOOCH (2007)

Now for anyone who thought I was being harsh on ABBA’s look might think my review of Scooch’s 2007 outfits contradictory or hypocritical… Regardless, I will continue to fight for these airline outfits that look like they’ve come from a vacuum packed Smiffys costume set or a knock-off version of Britney Spear’s air hostess outfit from her ‘‘Toxic’ music video. Either way, my opinion is definitely influenced by nostalgia (and the aforementioned retention of the song’s lyrics), the hilariously noughties frosted tips and the tiny pink headpieces. It also serves as a reminder that at least half of the Eurovision Song Contest entries nowadays are less than serious. With that said, it was a bit of a rough landing for Scooch and they came 22nd out of 24 contestants.

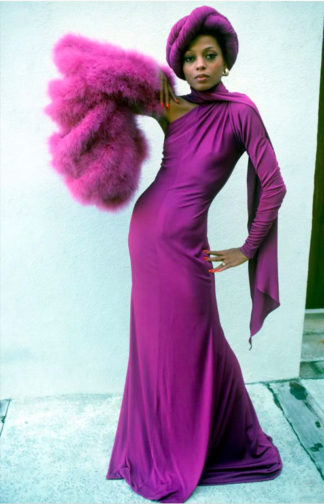

ONE: DANA INTERNATIONAL (1998)

This outfit undoubtedly stole the show back in 1998, merging fashion with costume. It was worn by Dana International, representing Israel, for her winning performance of Diva and historical feat as the first transgender woman to win the competition. This dress is from the 1997 Jean Paul Gaultier Haute Couture collection, and the multi-coloured parrot feathered jacket featured as Look 70. The simple, refined black V-neck maxi dress clings beautifully to Dana’s body and the feathery jacket forms an extension of her body, exaggerating every movement.

Furthermore, Gaultier is ‘a self-confessed Eurovision obsessive,’ as quoted in an interview for The Cut and has dressed several other high-profile contestants over the years, including Dana during her 2011 performance.

While I appreciate Eurovision mightn’t be everyone’s cup of tea, seeing how much joy it brings my mother can’t help but make me feel warmly towards Eurovision. But perhaps that’s why they say absence makes the heart grow fonder…because I no longer have to put up with listen to the Eurovision CD on repeat for two months each year.

And let’s keep our fingers crossed that the United Kingdom isn’t destined for another – pitiful – nul points this Saturday at the 2022 Eurovision Song Contest.

By Georgina Johnston-Watt

Bibliography:

https://assets.vogue.com/photos/5d924ac6c210350009cb1540/master/w_960,c_limit/_ALE0191.jpg

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RYxRIujyKgg&ab_channel=huelezelf

https://www.thecut.com/2013/05/gaultier-explains-the-eurovision-song-contest.html

https://www.vogue.com/fashion-shows/spring-1997-couture/jean-paul-gaultier