How can dress and fashion historical imagery be consumed thoughtfully through a platform designed to deliver “Insta” visual-gratification?

The name of the game is self-explanatory. Instagram is a digital landscape through which the inescapable consumption of countless images is organised into a curated virtual reality. A flurry of images is uploaded onto our personal, tailor-made feed daily, hourly—in fact, any time the app is refreshed on our device of choice. And this instantaneous cycle of viewing and sharing has become snuggly situated in our collective day-to-day narrative.

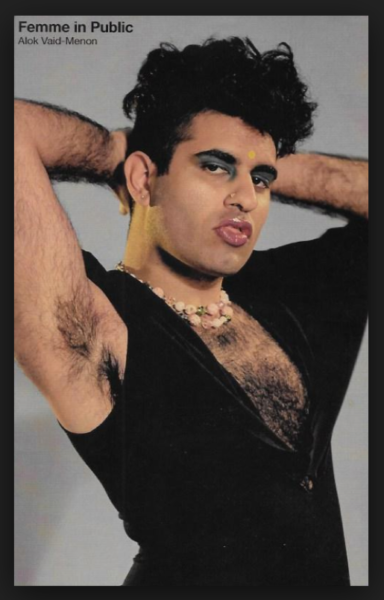

It is fair to say that fashion imagery, more specifically fashion photography, has become a firm feature on many an Instagram feed. Snapshots of contemporary collections are shared by Influencers from Fashion Week’s runway-adjacent front rows; models post Instagram Stories when on set, on location; and makeup artists upload videos of themselves mixing palettes when designing sponsored campaign looks. The content is constant and it is diverse, meaning that a fashion-centric aesthetic is now marketable to a wider portion of the Instagram community. But what does this mean for the tradition of fashion imagery—its dissection, discussion and the themes that underpin its discourse—and how are we now to consume said images in a way that preserves meaning and evokes critical analysis? If the volume of fashion and dress historical imagery being uploaded onto Instagram’s constantly shifting consciousness continues at such a rate, will it ultimately damage how it is read?

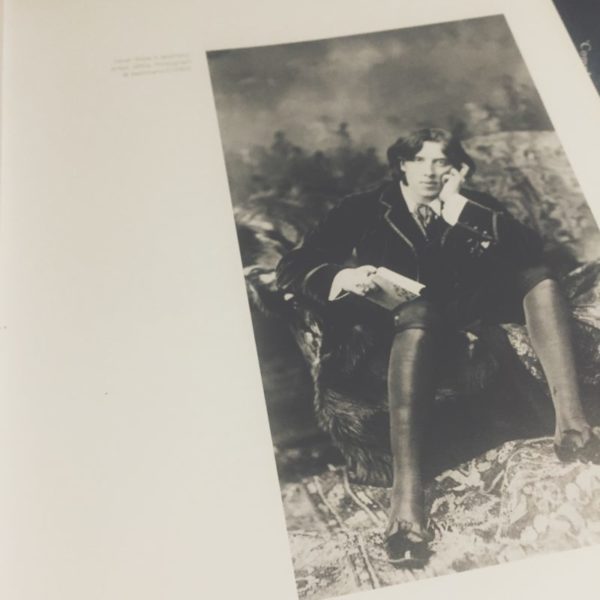

Take for example the trend for ‘fast-art’ on Instagram. You take a painting—either in its entirety or a key compositional detail—and post it with accompanying text. You devise a caption summarising the work’s basic details: its dimensions, medium, the date of execution and title, maybe even a brief yet spiffy artist’s bio, if you will. Then you post. Established accounts such as @paintings.daily or @historiadelart are good examples, and @painters.paintings neatly describe their account as ‘An Art History Tour in a Virtual Gallery.’

This exhibition-like design of posting is not exclusive to art historical accounts: it is also trending in the representation of art-historical dress and fashion. @the_corsetedbeauty, a well-followed dress account, claims to document “historical finery from days gone by. From the 18th century through the 1950s.” From the fashions flaunted in English Victoriana society portraits to the costumes designed by Michael O’Connor for Cary Joji Fukunaga’s 2011 adaptation of Jane Eyre, the account covers all manner of fashion foray, sweetly packaged into an aesthetically pleasing feed adorned with concise captions and analytically prevalent hashtags.

Its output, in accordance with that of accounts such as @redthreaded, @artgarments or @thiswasfashion, is undeniably a step in the right direction. However, in the majority of cases, we are given the essential information on the image without being asked to question it. What is this painting’s unique place in the art historical cannon? What does the dress being worn signify about its wearer? Can we discern the subject’s social status and which domestic interior is being depicted here? How are we to read the space in relation to the protagonist’s interaction with her friend, sister or even trusted domestic servant? There are many questions to raise in the reading of any image, but is Instagram the right space in which to begin this line of questioning?

Maria Aceituno of @historicalgarments thinks that, in the context of fashion history (which she believes has a different goal than that of modern fashion imagery, as it does not affect current designer purchases) ‘the use of social media for sharing fashion history images is affecting fashion consciousness. With more access to images, a wider audience is learning about the use, construction, and purpose of clothing in a more user-friendly manner. Searching with a hashtag yields a wealth of information. Captions that go along with these images can also help give new insights, correct misinformation, or even perpetuate myths **cough: corsets and missing ribs: cough**.’

I am inclined to agree with Maria, to an extent. It is encouraging to see accounts such as her own act as a dress/fashion history catalogue, potentially exposing a greater, more diverse audience to the discipline. But am I asking too much in my desire to be challenged by the content to which I am exposed? I dream of a time when I will reread captions with motive, when my interest is pushed enough to strike up a debate in the comments, when I am moved to ask for more insight over DM. I look forward to when I can interrogate and probe, as opposed to continually swiping the state of passivity in which I find myself, adequately educated, yet to be enthralled.

Please join us Friday 29 June, 2018 at the Courtauld Institute of Art 10:30am-12:00pm for a live recording of The Conversations with Jason Campbell & Henrietta Gallina podcast, open to all free admission

Please join us Friday 29 June, 2018 at the Courtauld Institute of Art 10:30am-12:00pm for a live recording of The Conversations with Jason Campbell & Henrietta Gallina podcast, open to all free admission