Is it a temple? Or a pagoda? When my partner and I were digitizing a section of Anthony Kersting’s photos taken in Norway, we were amazed, but then struggled to associate this unique-looking wooden building (fig. 1) with part of the Norwegian architectural tradition. Later research demonstrates that it was one of the stave churches — its name deriving from the pine tree trunks used to construct the building — constituting a part of the great cultural heritages of Norway and the rest of the world. A search into the Kersting archive for photos of similar churches, however, introduced me to a series of churches Kersting visited during his trip to Norway, each distinct in style and history. Fascinated by the contrasting designs of the churches, I wish to peek into the changing devotional experience in Norway using Kersting’s photos and the broader collection of the Conway Library on Norwegian ecclesiastical architecture.

Fig. 1: A black and white photograph depicting the Stave Church at Vik. The church appears to comprise of a single nave with a raised roof, which is topped with a bell tower and culminates in a smaller, pyramidal tower. The church is built and ornamented in dark wood. The points of the roofs extend out into dragon shaped wooden carvings. A rounded turret is visible on right side of the photograph. On the ground floor, a small entrance is visible within a simple wooden porch. The left half of the church is obscured by trees and surrounded by grass and vegetation, and a small number of white headstones can be seen in the graveyard outside.

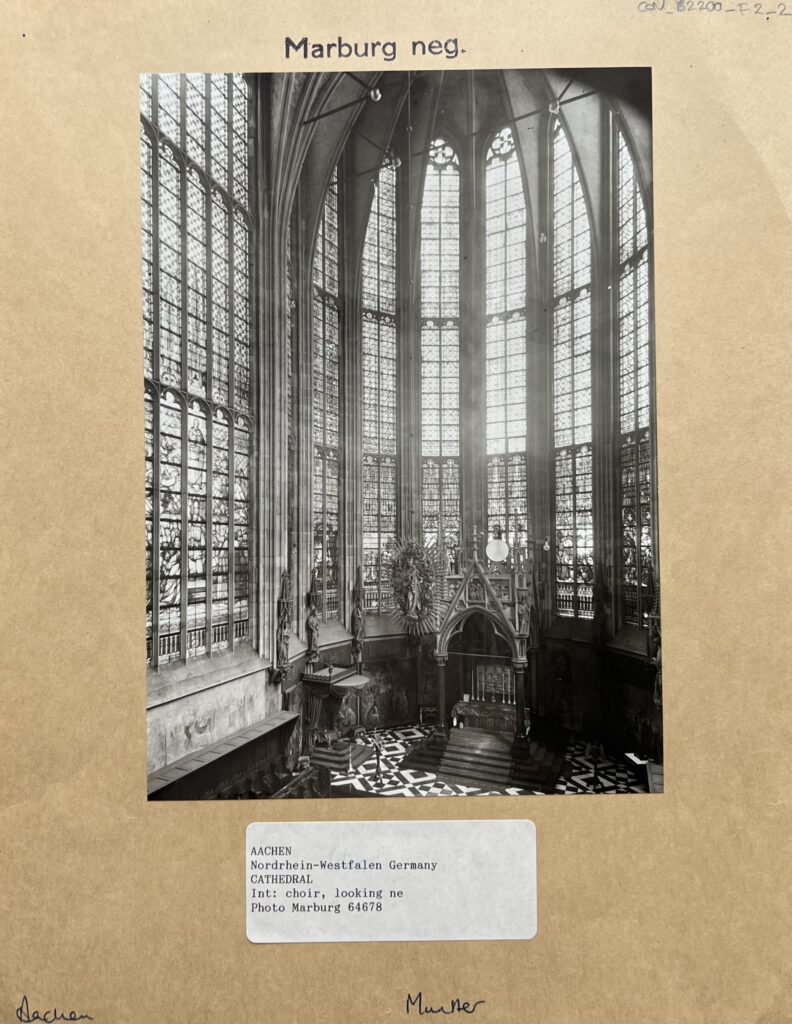

Fig. 1: A black and white photograph depicting the Stave Church at Vik. The church appears to comprise of a single nave with a raised roof, which is topped with a bell tower and culminates in a smaller, pyramidal tower. The church is built and ornamented in dark wood. The points of the roofs extend out into dragon shaped wooden carvings. A rounded turret is visible on right side of the photograph. On the ground floor, a small entrance is visible within a simple wooden porch. The left half of the church is obscured by trees and surrounded by grass and vegetation, and a small number of white headstones can be seen in the graveyard outside.

[KER_PNT_ H16811, The Stave Church at Vik, on the Bogn Fjord. Attribution: Anthony Kersting. The Conway Library, The Courtauld Institute of Art, CC-BY-NC]

Perhaps nothing better illustrates the contour of the history of religions in Norway than its churches — those disappeared, those still standing and those refurbished. While the polytheistic Norse religion filled people’s imagination of the spiritual world and their understanding of the natural world with stories of warring gods, since the 8th century gradual Christianization of the land began with converted Viking kings bringing their new religion home as they returned from England. King Olav Haraldsson — in particular, his death in 1030 CE — played a central role in Norway’s Catholic transformation. The alleged miracles associated with his tomb saw a massive number of conversions, his canonization and subsequent elevation into the patron saint of Norway, and the emergence of a cult of saints. Into the 16th century, Norway’s participation in the Reformation saw the royal family and the rest of the country breaking away from the Roman Catholic Church and converting to Lutheranism. Changes in the religious landscape of the country are reflected in the erection of new churches and the dismantling of old ones, as well as the adapted appearance of existing churches.

An adapted building not only reflects religious changes, but also calls for a closer examination of the devotional experience. As the ‘spatial turn ’prompted archaeologists to explore the interaction between landscape, building and material culture, Kate Giles theorizes the concept of visuality as “the social and cultural constructed-ness of vision” and the medieval way of seeing as a form of feeling… touching the object of vision” [1]. Giles’s work on pre-modern England provides valuable insight into studies on the surviving medieval churches in Norway, which, on top of demonstrating English influence, reflects regional interpretations of interactions between cultures and religions. Although Kersting did not document the evolution of one particular parish church, the geographical range of his photos allows one to appreciate the diverse religious architecture in Norway and to reimagine people’s unique memory of these transforming spaces. Many personal accounts of the churches were lost or yet to be told, but photos open a window for us to listen to the voices embedded in woods and stones.

The Exterior: Style and Material

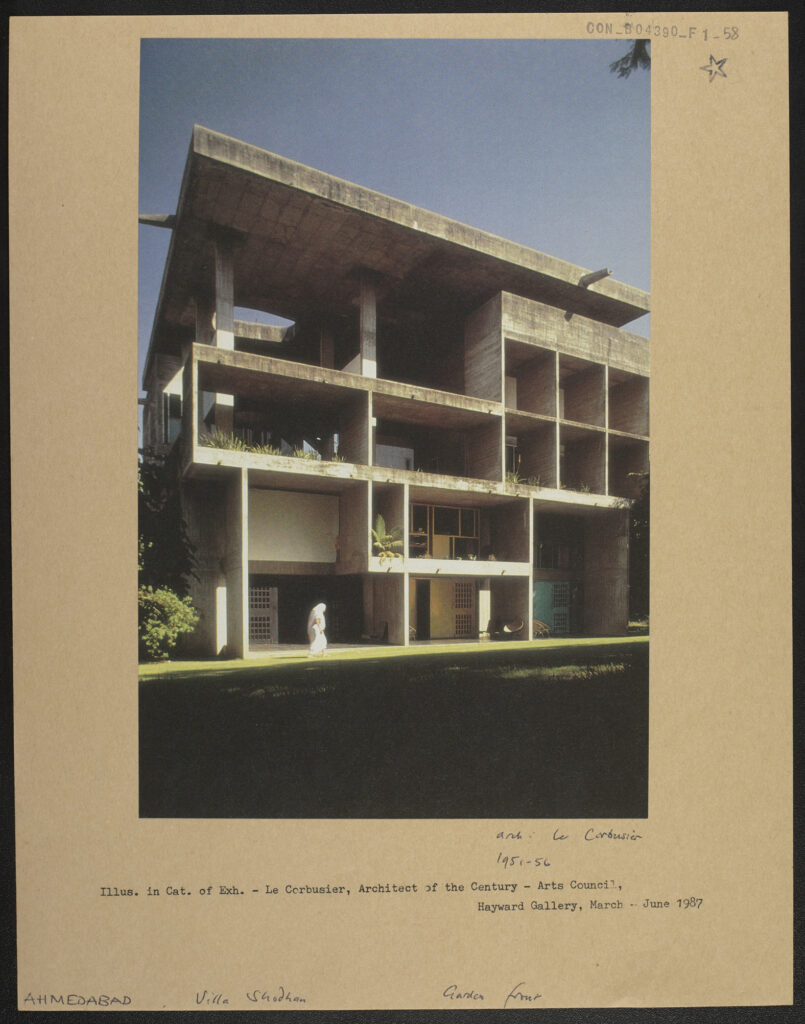

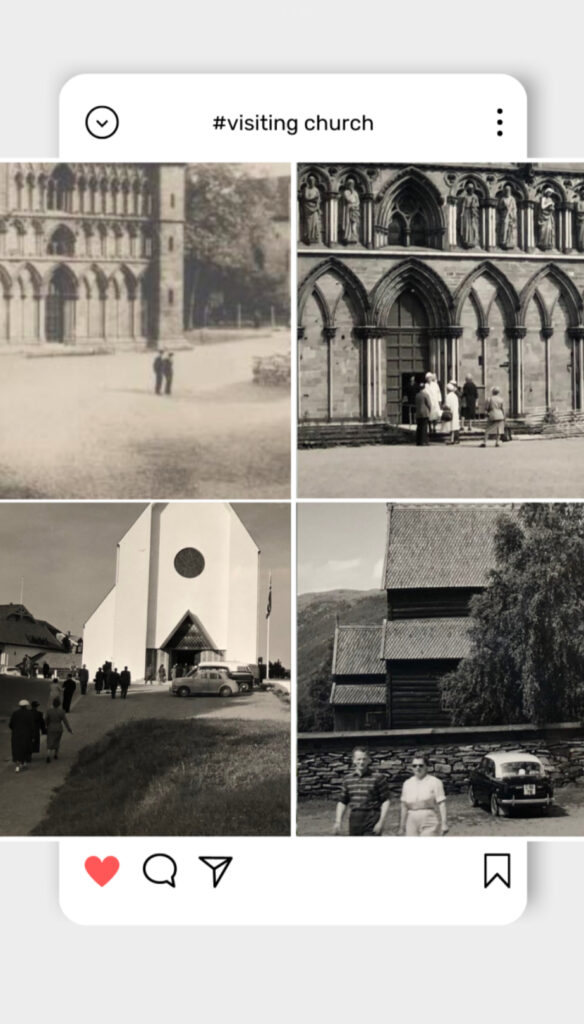

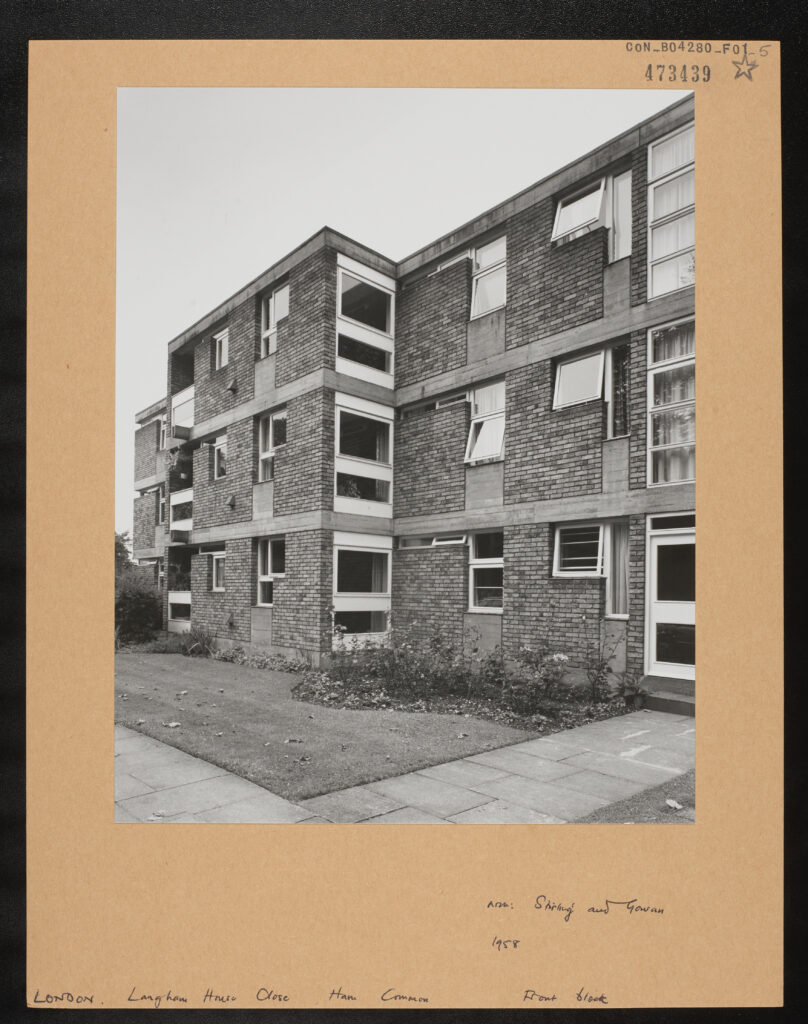

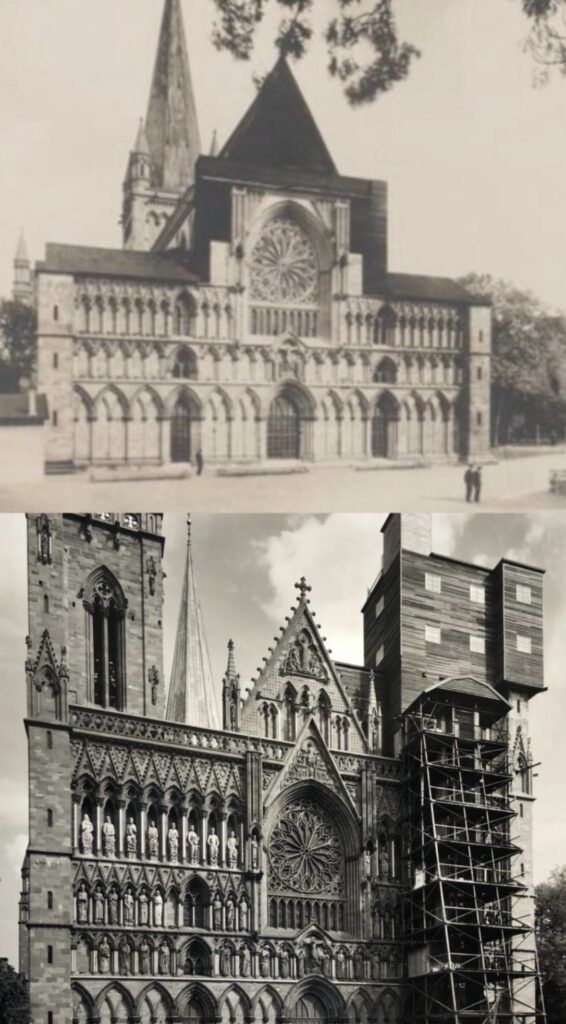

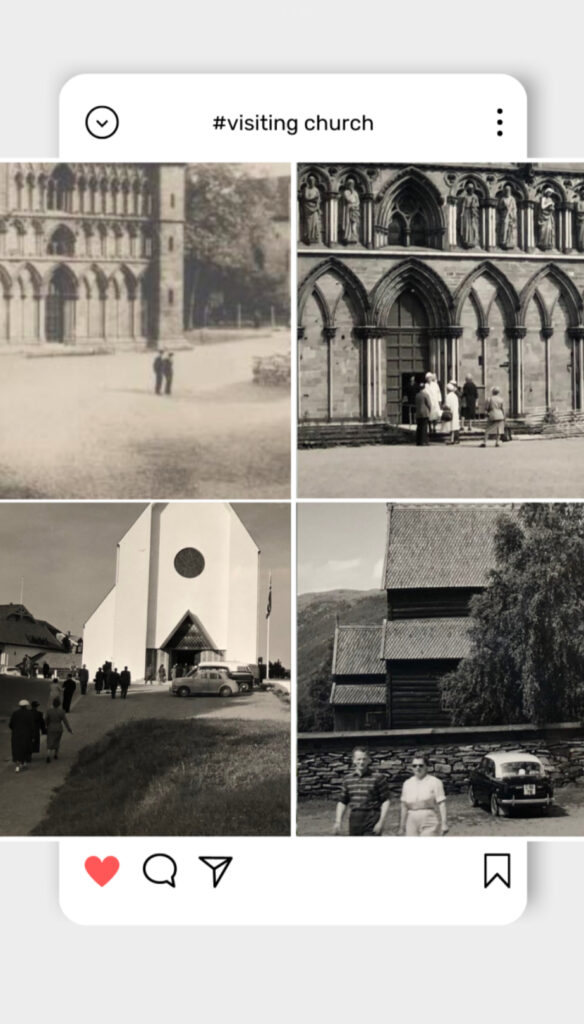

Browsing through the photographic collection often gives one the opportunity to see buildings of contrasting styles juxtaposed with each other. In this case, Kersting’s trip to Norway captures the distinct architectural styles adopted by medieval and modern churches, which can be made more even apparent through collage (fig. 2).

Fig. 2: Collage of parts of different churches on top of the image of the stave church at Vik, Yolanda (Yiyun) Huang, 2023.

From right to left: the Trondheim Cathedral [KER_PNT_ H19105. Attribution: Anthony Kersting. The Conway Library, The Courtauld Institute of Art, CC-BY-NC], the Kviteseid Old Church [KER_PNT_ G10336. Attribution: Anthony Kersting. The Conway Library, The Courtauld Institute of Art, CC-BY-NC] and the bell tower of the Cathedral at Molde [KER_PNT_ H13157. The Conway Library, The Courtauld Institute of Art, CC-BY-NC].

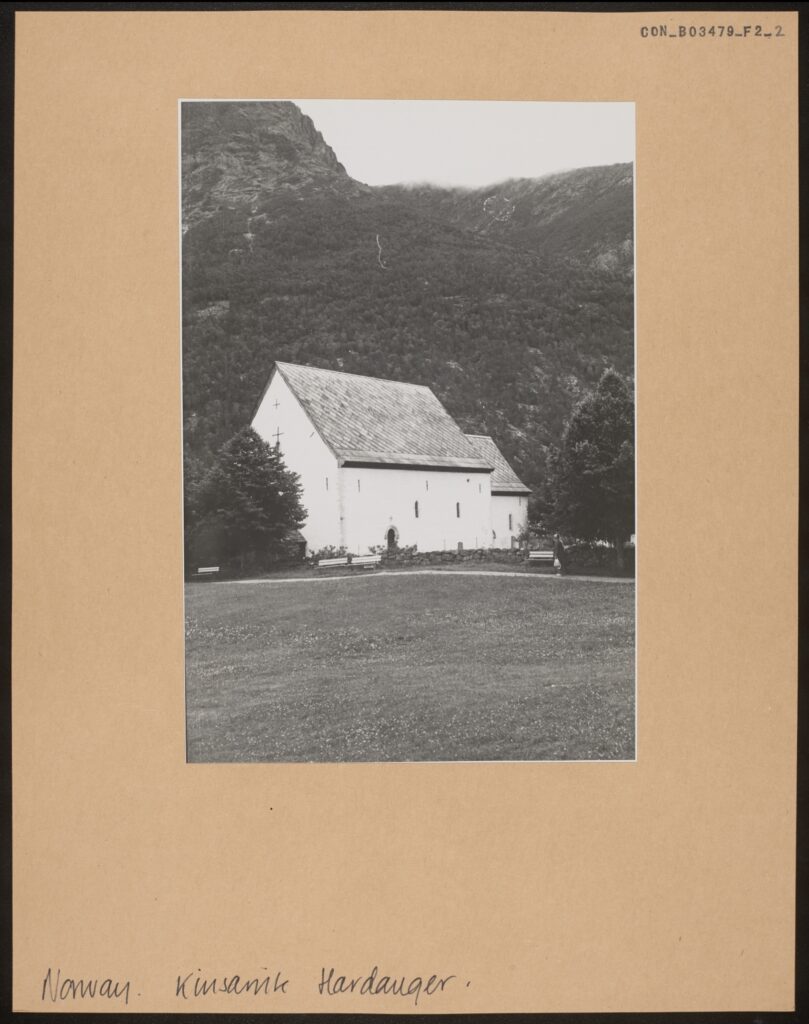

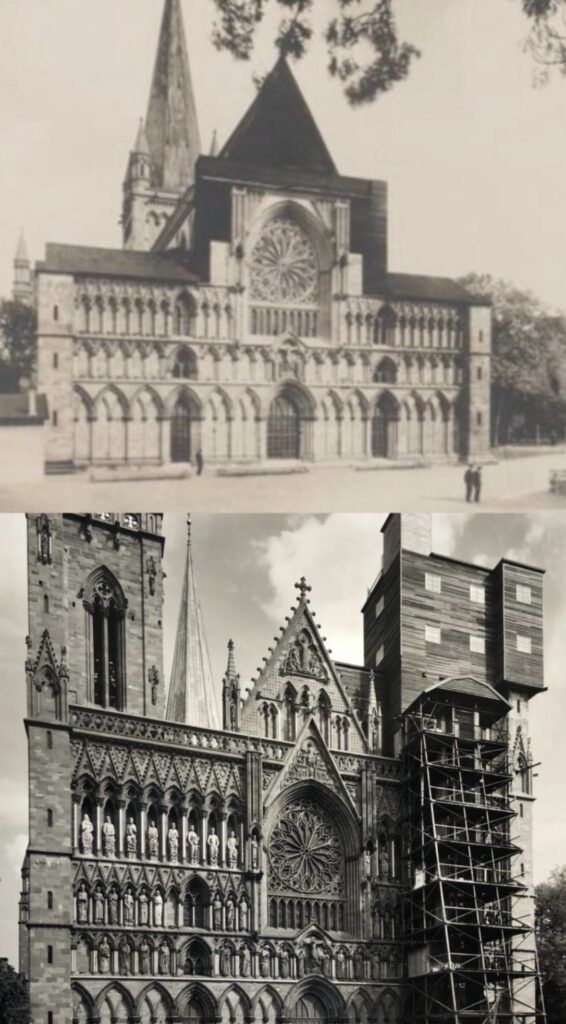

The Stave Church at Vik, built between 1130 and 1150, is one of the 28 remaining stave churches in Norway — scholars speculate that about 1000 more existed in earlier periods. While there has been no consensus on whether the stave churches represent a more indigenous style or were influenced by the English basilicas, they certainly draw visitors’ attention at first sight with their large, steep and multi-tiered pitched roofs connecting to the bell tower. Dated between the 12th to 14th centuries, the Trondheim Cathedral also features a sky-reaching bell tower in the center (fig. 3), but it displays extensive Romanesque and Gothic characteristics.

Fig. 3 Left: [See previous description of Fig.1]

[KER_PNT_ H16811, The Stave Church at Vik. Attribution: Anthony Kersting, The Conway Library, The Courtauld Institute of Art, CC-BY-NC]

Fig. 3 Right: A black and white photograph of the Trondheim Cathedral from the north. The photograph depicts a large cathedral, built in light stone. The architectural style is eclectic, encompassing both Romanesque and Gothic elements. The construction of the church is relatively simple, a nave with a bell tower extends upwards above a central entrance. Though not excessive, the ornamentation is significant. There is a curved tympanum above the entrance, which itself is set into a pointed porch. There are rows of stone windows only in the central section of the façade, which is flanked by two buttresses with simple, pointed pinnacles. There is a circular rose window set just below the point of the porch. The bell tower continues this ornamentation, also flanked by two pinnacles and culminating in a hexagonal point. A road leads to the cathedral, which is surrounded by trees.

[KER_PNT_ H13177, The Trondheim Cathedral, from the north. Attribution: Anthony Kersting, The Conway Library, The Courtauld Institute of Art, CC-BY-NC]

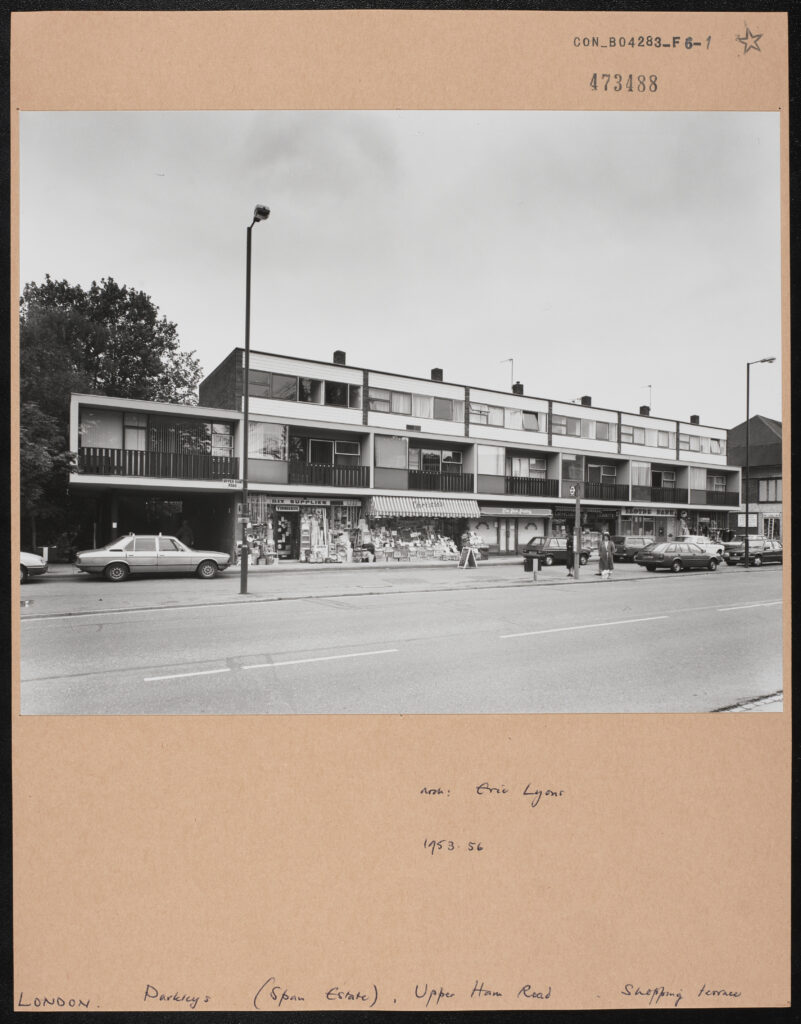

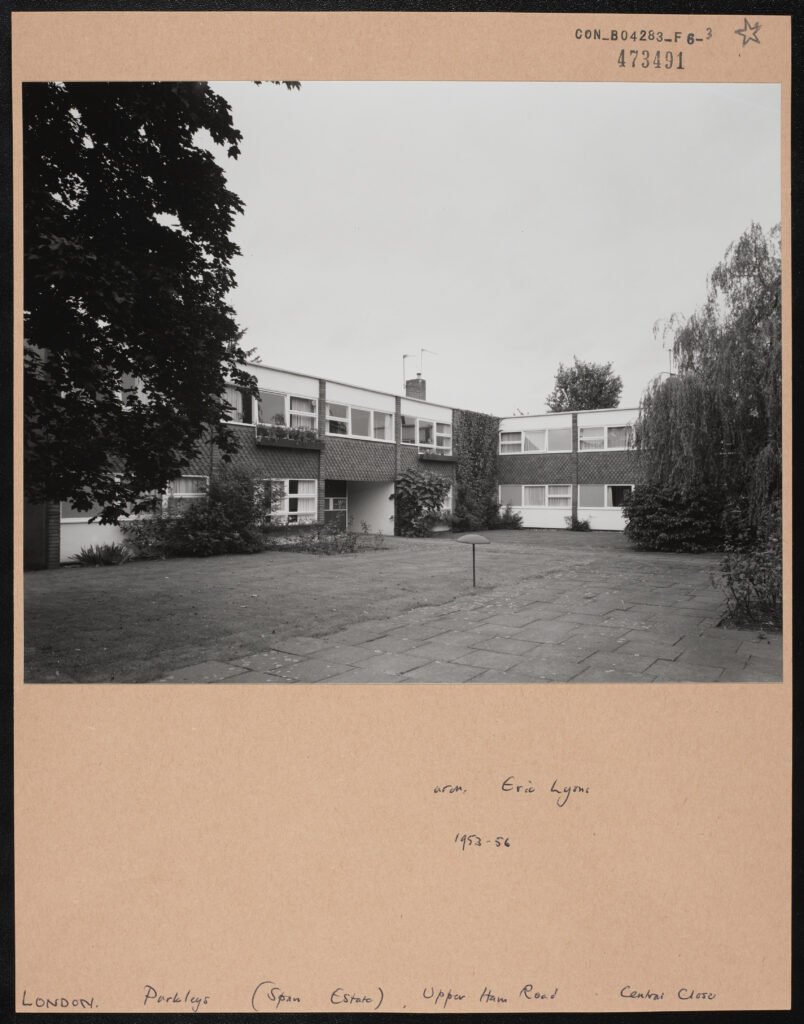

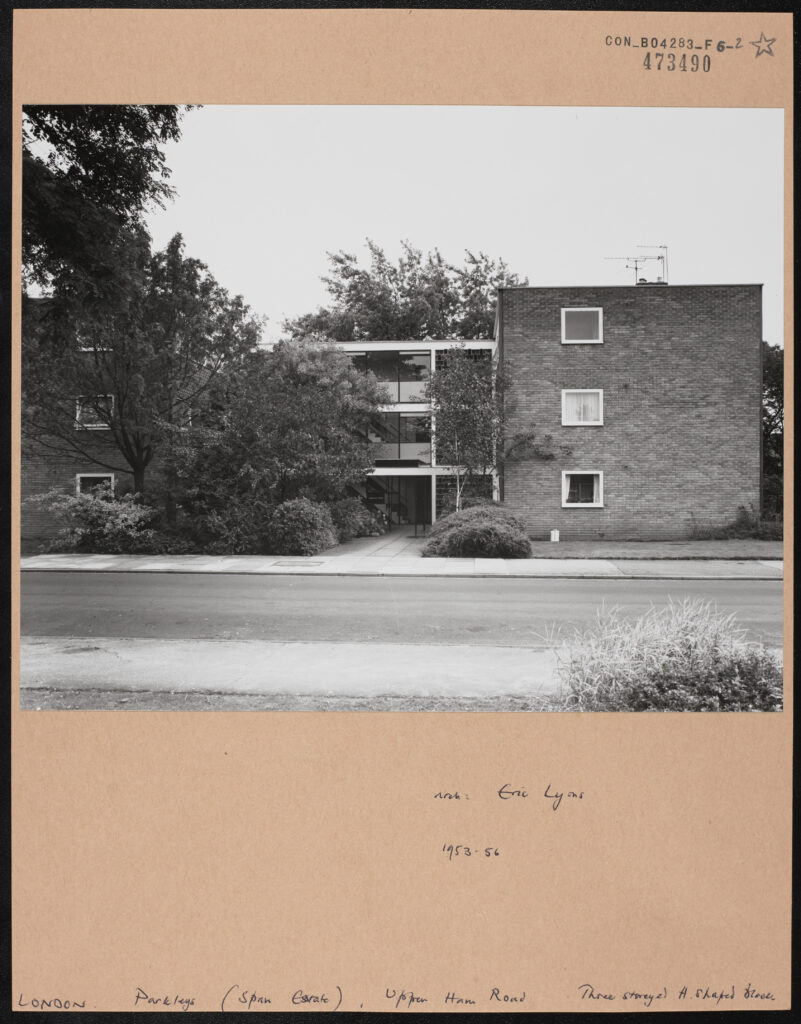

Dated to a similar period of the late 12th century, the Kviteseid Old Church in Telemark, however, is built in a Romanesque long church design typical of many among the 159 preserved medieval stone churches in Norway. The church at Molde also adopts a long church basilica design, but it demonstrates striking characteristics of a modern and functionalist style in the 1950s, with a detached bell tower (fig. 4).

Fig. 4 Left: A black and white photograph depicting the exterior of the Kviteseid Old Church at Telemark. The church’s façade is simple, white stone, and the church comprises of two main parts: the main building, with a single nave, raised roof and porch, and a smaller choir section to the right. The roof is decorated with light tiles, and at the points there are miniature decorative pinnacles. On the main façade, there are two arched windows to the right of the entrance porch. The porch has a pointed roof, with a crucifix atop the point. There are a set of stone steps leading to the entrance door, which is flanked by carved wooden columns. The choir is decorated in a similar fashion, with a single small window and door. The church grounds are quiet, with trees behind and a small graveyard in front, from which numerous gravestones and crosses can be seen. The church is bordered with a rustic stone wall.

[KER_PNT_ G10336, The Kviteseid Old Church, in Telemark. Attribution: Anthony Kersting, The Conway Library, The Courtauld Institute of Art, CC-BY-NC]

Fig. 4 Right: A black and white photograph depicting the Modern Church at Molde. There are two main buildings in the centre of the photograph, the main body of the church and a free standing bell tower to the right. There are also visible smaller buildings on either side. The main church building contains no ornamentation, and is a simple double nave church built in flat white stone. There is a dark, circular window in the centre of the façade, and a small, pointed entrance on the ground floor. This is where the only decoration is, as the walls either side of the entrance are patterned with stripes, and the tympanum is a tessellated diamond pattern. The bell tower is built in white stone, excluding the roof, which is dark grey and culminates in a metal pinnacle. There is also a simple, white clock face on the roof, and the main body of the bell tower is hollow with a white stone exterior. The bottom floor mimics the white stone exterior with the recesses filled in with brick walls. The different levels are surrounded by metal railings which wrap around the entire tower. Two separate roads can be seen to lead to the church with a grass verge between them.

[KER_PNT_ H13157, The New Church at Molde. Attribution: Anthony Kersting, The Conway Library, The Courtauld Institute of Art, CC-BY-NC]

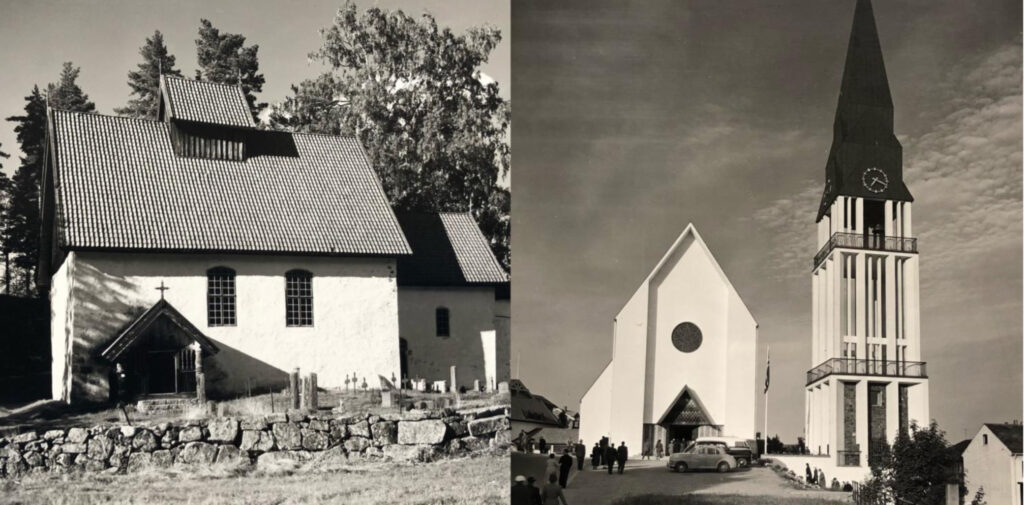

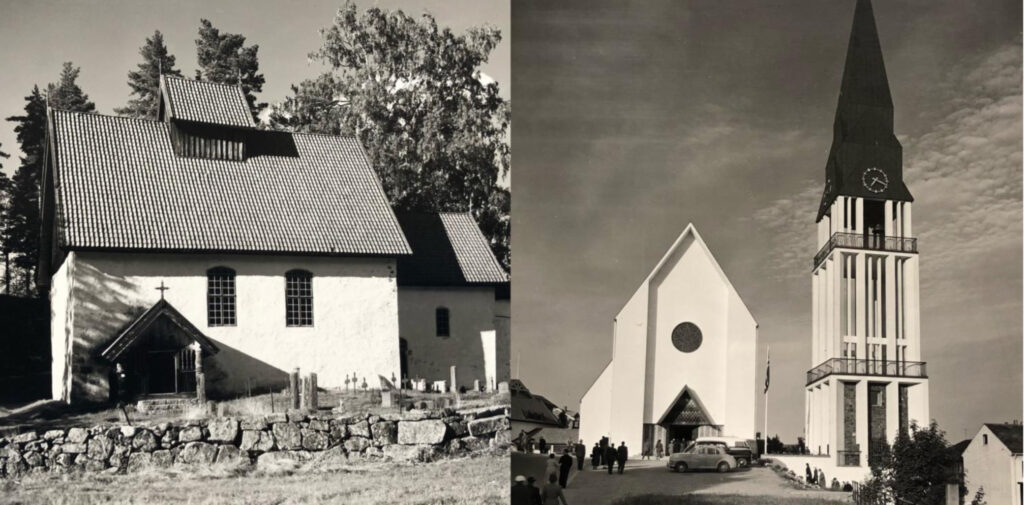

The differences in styles may be more closely observed in the doors (fig. 5). A semicircular structure, for example, can be seen in both the door of the Stave Church at Lom and the Trondheim Cathedral, but the former was much narrower and had an intricate wooden carving of pagan abstract animal images. As the main entrances to the church, the doors — with their form and carving designed to convey meaning — guard the sacred space behind them, differentiating while connecting the inside to the mortal world.

Fig. 5: From left to right: The first door is a simple curved arch. The columns supporting the arch as well as the arch itself are made of ornate carved wood. The second door is a pointed church porch topped with a crucifix. The entrance is flanked by stone columns and a small set of stone steps. The third door is a more extravagant curved arch which is layered and decorated with a zigzag pattern. The final door is another porch, but is more modern, decorated with a tessellating diamond pattern under its gable roof, and with large striped columns to either side. [Detail of the doors of the Stave Church at Lom, the Kviteseid Old Church, the Trondheim Cathedral, and the Church at Molde]

Similarities in architectural style aside, it is the primary building material employed that further distinguishes the churches and people’s experience in the spaces from each other. The stave churches stood out because of their use of wood trunks, reflecting resources and skills inherited from the Viking ship-building tradition. Breathing in the scent of tarred wood and observing darkened wood as it changes color in time, one wonders whether the stave churches give visitors a uniquely soft, personal and sensory-rich experience to which the white stone churches of the same period could not compare. The major shift from wood to stone did not happen until the 16th century [2]. White remains the dominant color of many later churches, but modern churches like the one at Molde used concrete and plastered surfaces, giving a very different material feel to the aged white stone walls of the Kviteseid Old Church (fig. 6 and 7).

Fig. 6 Left: [See description for Fig. 4 Left]

[KER_PNT_ G10336The Kviteseid Old Church, in Telemark. Attribution: Anthony Kersting, The Conway Library, The Courtauld Institute of Art, CC-BY-NC]

Fig. 6 Centre: [See description for Fig. 1]

[KER_PNT_ H16811, The Stave Church at Vik, on the Bogn Fjord. Attribution: Anthony Kersting. The Conway Library, The Courtauld Institute of Art, CC-BY-NC]

Fig. 6 Left: [See description for Fig. 4 Right]

[KER_PNT_ H13157, The New Church at Molde. Attribution: Anthony Kersting, The Conway Library, The Courtauld Institute of Art, CC-BY-NC]

Fig. 7: From left to right: Recent full color photos of the Kviteseid Old Church, the stave church at Vik, and the Church at Molde.

The Interior: Space, Light and Decoration

The change in the use of building materials is part of the trend of “dark, small and cold churches being replaced by bright, big and warm churches.” The expanding woship space is clearly reflected in Kersting’s photos (fig. 8). The left shows the interior of the Kinsarvik Old Church in the Hardanger and the stave church at Vik, respectively seating about 240 and 350 people. The right shows the Trondheim Cathedral and the Cathedral at Bodo, respectively seating about 1850 and 850 people. The majesty of the Trondheim Cathedral can be explained by its nature as a pilgrim site and venue for the consecration of new kings, but the scale of the Cathedral at Bodo has become conventional for churches (re)built in the 20th century.

Fig. 8 Upper Left: A black and white photograph depicting the interior of the Stave Church at Lom. The interior is made entirely of wood, and comprises of a central nave with a raised roof supported by wooden beams. There are two visible aisles to either side of the photograph, which are set behind loggias punctuated by thin, wooden beam columns. Above this, there is an open gallery, with wooden balustrades decorated with large decorative diagonal crosses. The gallery is also punctuated with columns, though these are rounded and not unlike doric columns, joined together by arches. Hanging from the centre of the ceiling is a chandelier, and behind it the chancel screen is visible. Beyond the screen, an ornate carved portal arches over the altar, and carved angels flank a painting on the altarpiece. The altarpiece is surrounded by a small, decorative balustrade. A heavily decorated pulpit is visible to the right of the photograph, and there are two rows of wooden pews filling the central floor space.

[KER_PNT_ H16796, The Interior of the Stave Church at Lom. Attribution: Anthony Kersting, The Conway Library, The Courtauld Institute of Art, CC-BY-NC]

Fig. 8 Upper Right: A black and white photograph depicting the interior of the Trondheim Cathedral. The interior is decorated in the Gothic style, and is heavily ornamented. The nave is very large, with aisles to either side enclosed in a richly ornamented loggia punctuated by Corinthian columns. These are further mirrored by smaller decorative Corinthian columns on the interior walls of the aisle, with pointed arches joining them together. The ceiling of the nave is also decorated by dark coloured ribbed vaulting, and the space is lit by thin, hanging lights. Towards the choir, there is a chancel screen taking the form of a large pointed archway flanked by two smaller copies. Above the central arch is a decorative entablature, which itself is topped with a statue of Christ on the cross. This is accompanied by two smaller statues, likely of saints, on either side. The rest of the chancel screen is made up of rows of smaller pointed arches. On the ground floor, there are rows of many individual chairs which stretch back of the threshold of the nave.

[KER_PNT_H13190, Interior of the Trondheim Cathedral, Attribution: Anthony Kersting, The Conway Library, The Courtauld Institute of Art, CC-BY-NC]

Fig 8. Lower Right: A black and white photograph depicting the interior of the choir loft of the cathedral at Bodo. The ceiling is curved, with a raised central section spanning the entire space. There is minimal ornamentation, with light coloured concrete walls and a simple repeating dot pattern running down the centre of the ceiling. The interior walls are lined with dark coloured artworks and hanging metal lights in the modernist style. The floor is similarly plain, with rows of dark wooden pews. There is a modern chancel screen at the front of the choir, with brick walls either side. Behind there is a pulpit and altar, with a tall, narrow stained glass window on the back wall depicting the crucifixion.

[KER_PNT_H13205, Interior of the Cathedral at Bodo. Attribution: Anthony Kersting, The Conway Library, The Courtauld Institute of Art, CC-BY-NC]

Fig. 8 Lower Left: A black and white photograph depicting the interior of the Kinsarvik Old Church in the Hardanger. The space is open and light, with white stone walls with little decoration. There are three arched recesses in the walls, two larger arches on the left and right, and a smaller arch at the top centre. The larger recesses are covered by wooden covers, and the smaller at the top contains a miniature architectural model of a cathedral. Dark wooden beams span the perimeter of the walls. The floor is made of simple wooden planks, and there are numerous rows of wooden pews in the central space. There is a large, curved arch door beneath the smallest recess, through which a densely ornamented altar is visible, covered by a cloth, with two single candlesticks flanking a seven-branched candlestick at the centre. Behind this is an altarpiece, comprised of a selection of six religious paintings bordered by a carved wooden frame. Within the large central space there is a decorated wooden pulpit to the left, surrounded by painted wooden panels depicting various saints. Above the pulpit is a carved, octagonal ‘roof’ which appears to be suspended from the ceiling. Finally, a large metal chandelier hangs from the centre of the ceiling.

[KER_PNT_H20213, The interior of the Kinsarvik Old Church. Attribution: Anthony Kersting, The Conway Library, The Courtauld Institute of Art, CC-BY-NC]

Perhaps not obviously shown in the black and white prints, but a visit to the above churches definitely gives you a clear feeling of the differences in the amount of light shining in through the windows. The small, high-up windows in the medieval churches work to create a mysterious and contemplative atmosphere in line with the enclosed space decorated with stylized pagan figures, while the bright light shone through the elegant sweeping curves of the gothic windows renders an extra layer of holiness upon the nave and choir.

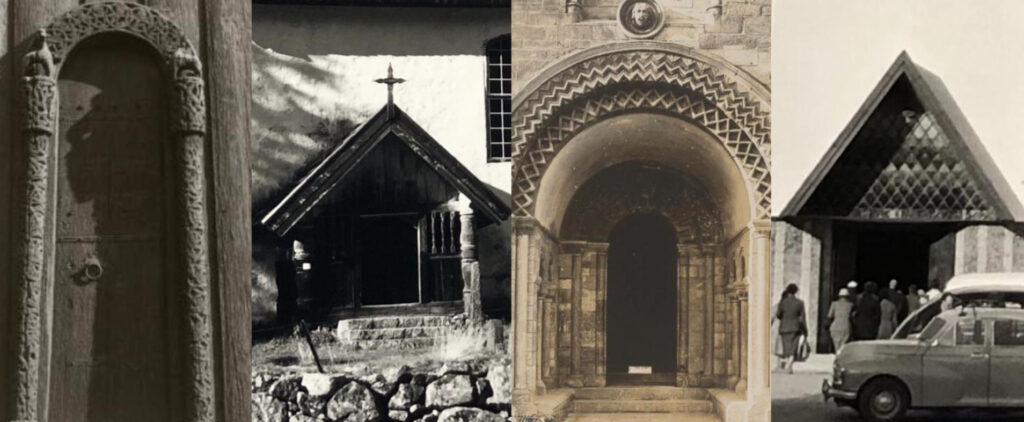

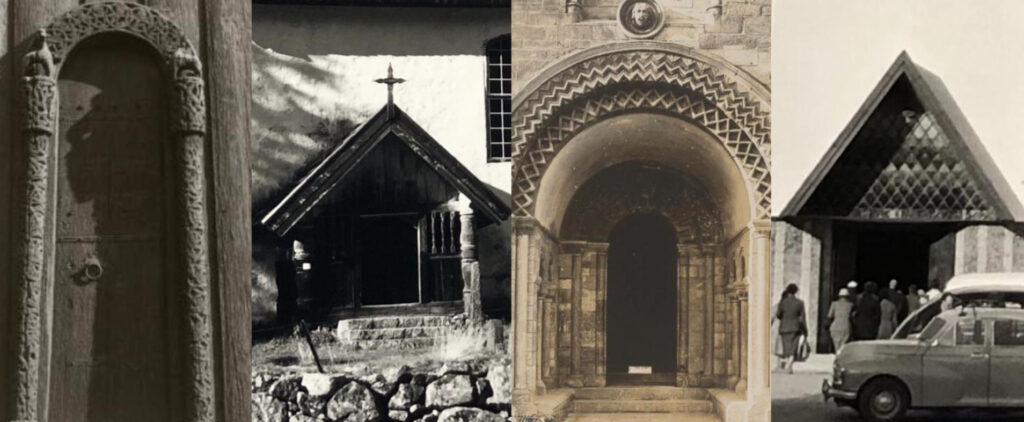

Meanwhile, it is often necessary to point out individual characteristics of the lighting design in certain churches to better appreciate the unique local memory they carry. The Kinsarvik Old Church in the Hardanger, for example, evokes tourists’ curiosity with its high-up windows on the west gable (fig. 9). In this case, instead of illuminating religious figures and spaces, the position and size of the windows seem to be more closely connected to the church attic up to which they lead — the attic was used to store ships sails and masts during the winter [3].

Fig. 9: A black and white photograph mounted on card depicting the Kinsarvik Old Church at a distance. The church is a brilliant white, with a simple stone façade that contrasts against the dark trees and mountains behind the building. The gable roofs of the main church building and smaller choir are tiled in a diagonal striped pattern. The façade of the front gable is similarly plain, with a single small window and two crucifixes visible. On the other façade, two slightly larger windows are visible, as well as a simple arched doorway. The church is surrounded by a rustic stone wall, several trees, and benches. Beyond the church is a large lawn.

[CON_B03479_F002_002, The Kinsarvik Old Church in the Hardanger. Photographic print on mount. The Conway Library, The Courtauld Institute of Art, CC-BY-NC]

The new Church at Molde, rebuilt after the war, also features a special design: the windows on the right are much higher than those on the left, changing the symmetry of the building and the source of light (fig. 10).

Fig. 10: A black and white photograph depicting the interior of the New Church at Molde. The nave ceiling forms a pointed arch, and is decorated with what appears to be a painted geometric pattern. Rows of metal light fittings hang from the ceiling along either side of the nave. On the left side, there also appears to be a wooden model of a ship hanging from the ceiling. The interior walls are simple, painted white, with an aisle on the left side of the composition. Dark coloured modernist columns punctuate the aisle, and a glimpse of a painting can be seen at the far end of the aisle space. To the right, the wall is made of white brick, and lined with three tall, narrow windows. There are many rows of dark wooden pews lined up on either side of the nave which extend to the pulpit and altar. On the left wall in front of the altar is a black and white patterned pulpit, and to the right is a simple crucifix. At the very back, there is a large altarpiece comprised of a central, rectangular portrait and three smaller square pieces, arranged into the shape of a cross. Directly above this, on the interior wall of the nave, there is a small, triangular window.

[KER_PNT_ H13159, The interior of the new Church at Molde. Attribution: Anthony Kersting, The Conway Library, The Courtauld Institute of Art, CC-BY-NC]

The amount of light dims or illuminates the faces and figures drawn or carved onto the walls and columns of the church. While each church discussed above has its interior decorated with rich human, animal and divine figures, I wish to especially draw attention to the two figures of angels.

The first is a painting on the north wall of the Kinsarvik Old Church, depicting a devil beneath the archangel Michael. The second shows a part of the painting ‘Easter Morning’ by the Norwegian Artist Axel Ender, in which an angel raised the arm to guard Christ’s empty tomb (Fig. 11).

Fig. 11 Left: A black and white photograph depicting a wall painting of the devil and the archangel Michael. The figure of the devil is significantly smaller than that of Michael, and is using a poker to attempt to tip his scales of judgement over to the side. The devil is depicted as animalistic, with large claws, with a smaller winged minion to his right. Archangel Michael is shown to tower over the devil, his wings outstretched and consuming almost the entire wall. The painting shows signs of extensive damage or weathering, and much of its detail has been lost.

[CON_B03479_F002_006, Painting on the North Wall of the Kinsarvik Old Church. Photographic print on mount. The Conway Library, The Courtauld Institute of Art, CC-BY-NC]

Fig. 11 Right: A black and white photograph depicting a painting of an angel guarding Christ’s tomb on Easter Morning. The angel is depicting sitting on some steps, dressed in white with full white feathered wings. She holds one hand aloft, looking outwards to the exit of the tomb.

[KER_PNT_ H13160, the painting “Easter Morning,” now forming the altarpiece of the north aisle of the new Church at Molde. Attribution: Anthony Kersting. The Conway Library, The Courtauld Institute of Art, CC-BY-NC]

Both forming an eye-catching and dominating presence on their respective walls, the figures of angels demonstrate very different initiatives from the artists and evoked distinct memories of modern-day church-goers. With its informal, monochrome style, the archangel Michael and a devil painting could represent a familial or personal effort to transcribe their religious identity into something visible and tangible. The presence of a devil trying to tip the scale of the soul inside a devotional space could be disturbing to medieval and modern audiences alike, but the figure of Michael towering over the devil might as well offer a sense of protection against evil.

On the other hand, “Easter Morning” was originally in the old Church of Molde destroyed during the Second World War. The fact that this particular painting had been previously removed for safekeeping and now forms the altarpiece of the north aisle of the new church creates a precious sense of continuity between the modern church and its disappeared predecessor, while further strengthening the new church as a symbol of security, hope and new direction.

The Environment: Changing Space and Use of Space

As the history behind the rebuilt church of Molde suggests, images of churches often give the viewer a false impression of an unchanging religious and cultural symbol standing against the erosion of time. The reality, in fact, is that many of the churches discussed above underwent destruction, reconstruction and adaptation. So instead of capturing their timeless beauty, photos actually encourage us to explore the ever-changing appearance and cultural significance of the churches to the locality.

Being a manifestation of the Norwegian cultural identity that combines Christian and Viking themes, the stave church at Lom was constructed in the 13th century but has a 17th-century addition of transept and sacristy — re-adapted to fit a new form of Christianity in the radical transformation to Lutheranism. Similarly, in the stave church at Vik survived an altar screen and chapel — a later addition depicting the nativity of Jesus in an English/French style (fig. 12). In addition to the Lutheran re-adaptation, the difficulty of preserving wood means that the remaining stave churches more or less underwent rebuilding — something one can look for in the lighter-colored, thus newer, wooden walls.

Fig. 12: A black and white photograph depicting one of the altars at the Stave Church at Vik, contained underneath a wooden portal. The portal comprised of a curved archivolt standing on four wooden legs, and its roof contains many ornate carvings, with filigree-like patterns about the archway to the front. It is further decorated with carved icons, one on each of the wooden legs, and a larger one at the point of the arch. The interior of its roof is painted with a selection of religious scenes. Underneath the portal, there is a white stone altar covered with black cloth. A curved doorway is visible to the right of the photograph, and this too is carved wood with smooth wooden columns. The rest of the wall, which stretches behind the portal, is punctuated with a row of small arched windows. A gallery is visible above the door and portal, and is enclosed behind a broad balustrade and large columns. A metal chandelier hangs from the ceiling in the centre.

[KER_PNT_ H16812, One of the wooden altars in the Stave Church at Vik. Attribution: Anthony Kersting. The Conway Library, The Courtauld Institute of Art, CC-BY-NC]

Standing at the center of the traditional pilgrim destination, the majestic Trondheim Cathedral in fact witnessed numerous additions and renovations since its established and into the 2000s. Kersting managed to capture one moment of reconstruction work on the never-completed west front, with a temporary modern structure concealing the work to be done. An earlier photo from the Conway Library gives us another look of the west front before the new figures of saints and kings in the niches were installed (fig. 13).

Fig. 13 Top: A black and white photograph depicting the west front of the Trondheim Cathedral. The façade is built in the Gothic style, with a large rectangular section on the ground floor which is decorated with rows of arched recesses. In the future, these recesses will come to house a multitude of sculptures of various figures, but in this photograph they are empty. The rectangular section of the façade is split into three main parts: a strip of narrow, pointed recesses at the top, rows of shorter recesses in the centre with clover shaped arches, and much wider pointed arches along the ground floor. On each section, there are two windows, apart from the ground floor, which has three doors. At the top of this rectangular section, in the centre there is a large stained glass rose window, with a row of smaller, narrow arched windows underneath. Surrounding the rose window is a square, dark wood structure which mimics the tiles on the roof of the west façade. This, in turn, is topped with a large dark wood pyramid. Beyond the façade, a large pointed bell tower is visible, which culminates in a metal crucifix.

[CON_B03484_F001_001, Trondheim Cathedral, West Front: General views before restoration. The Conway Library, The Courtauld Institute of Art, CC-BY-NC]

Fig. 13 Bottom: A black and white photograph depicting the west front of the Trondheim Cathedral. There is a large amount of scaffolding about the cathedral’s right side, where a simple, square wooden structure has been built over a tower to the right of the composition. This structure is built with wooden planks, giving it a striped appearance. There is another tower to the left, built in the Gothic style, with square flat roof with pinnacles at each corner. The roof also possesses a decorative balustrade with a clover pattern. Set into the tower is a tall, narrow arched window. In the centre of the façade there is a pointed gable with a decorative relief, this too is ornamented with pinnacles and a row of smaller arched recesses. The central façade of the cathedral is richly ornamented, with rows of sculptures of various figures set into arched recesses in the wall. There are minimal visible windows, with most of the space being occupied by these sculptures. In the very centre of the facade, there is a large stained glass rose window, with a row of narrow arched windows underneath, topped with another gable decorated with a carved relief.

[KER_PNT_ H19105, The West Front of the Trondheim Cathedral. Attribution: Anthony Kersting. The Conway Library, The Courtauld Institute of Art, CC-BY-NC]

Changes happened in the exterior and interior of the churches but also in the ways people use these spaces. A few medieval churches such as the Kinsarvik Old Church remain close to the public but continue to host sacred concerts and events. Yet most stave churches have become tourist sites with little or no religious activities. The shift in the nature of the space reminds one to think about the changing relationship between the building and its surrounding — the physical world and the people who live in it.

Fig. 14 Instagram post of details of visitors going in and out of the churches in previous figures.

Many Norwegian churches were built in proximity to nature, making the surrounding environment and traveling to go to churches a central part of the medieval religious experience. The Kinsarvik Old Church was located at the junction of the fjord Hardangerfjord and the Sørfjorden, meaning that many locals would row their boats to attend church. Stave churches like the one in Vik are often located between mountains and rivers, speaking into the intricate wood carvings which drew inspiration from nature (fig. 15). In the present day, however, the natural environment — and the effort to go into the mountains — became an integral part of the tourists’ quest to find and visit the distant monument of ancient culture.

Fig. 15: A black and white photograph depicting the Hopperstad Stave Church at Vik from a distance, partially obscured on its left side by trees. Only the multilevel roof is visible, with a pyramidal bell tower at the apex, which attaches to a smaller gable at its base. The gable then sits atop the raised roof above the nave, which in turn connects to the main structure of the church. The points of the corners of the roof all extend out into small carved dragons. A smaller structure is seen in front of the church, which appears to be a hollow portal with a gable roof. In the distance, behind the church, a steep grassy mountain is visible. A small dirt road leads to the church, and the side of a simple wooden building can be seen to the right of the photograph.

[KER_PNT_ G5534, The Hopperstad Stave Church at Vik. Attribution: Anthony Kersting. The Conway Library, The Courtauld Institute of Art, CC-BY-NC]

The wood is not only a source of ancient cultural inspiration, but also of anxiety about preservation and destruction. News in 1996 articulated the worries about the homegrown Satanist movement whose slogan was “Kill the Christians, burn their churches.” More than 20 stave churches were destroyed by arson in the early 1990s [4]. Entering the millennium, stave churches stood between the dilemma of preservation and tourism. The study conducted by the Stave Church Preservation Programme in 2015 shows that a door sill in one stave church was worn down by 0.50–1.50 mm during the year [5]. With different churches taking different scales of protective measures, the sacred, historical wood symbolic of Norwegian identity continues to be subject to the threat of disappearance.

Photos capture the building at one historical moment, but they encourage one to look beyond that moment. The changing space and visuality documented by Anthony Kersting and collection of the Conway Library allow us to explore the hidden narratives behind wood and concrete, reimagining people’s shifting devotional experience and memory in transformed architectures.

References

[1] Giles, K., ‘Seeing and Believing: Visuality and Space in Pre-Modern England’, World Archaeology, 39/1 (2001), pp. 105-121

[2] Cook, W. R.,‘Episode 11: The Stave Churches of Norway’, The World’s Greatest Churches (2014) [3] Emma, ‘Hidden Secrets at Historic Kinsarvik Church’, https://thehiddennorth.com/historic- kinsarvik-church/, written on November 11 2022, accessed on June 21 2023

[4] Caryl, C., ‘Staving Off the Devil’s Flames’, The Wall Street Journal Europe, (23 August 1996)

[5] Berg, F., ‘Wear and Tear of World Heritage: Preventive Conservation and Tourism in Norway’s Stave Churches,’ Studies in Conservation, (2018), pp. 320-322

Yolanda (Yiyun) Huang

Courtauld Connects Digitisation

Oxford University Micro-Internship

Participant

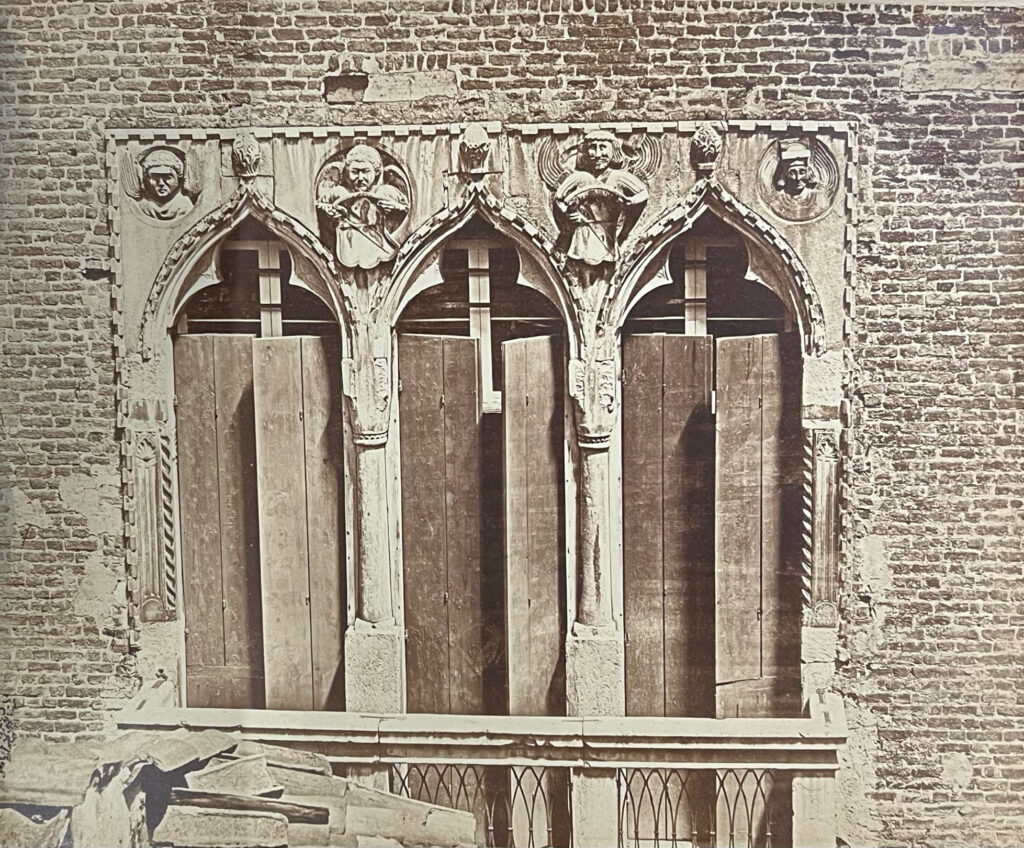

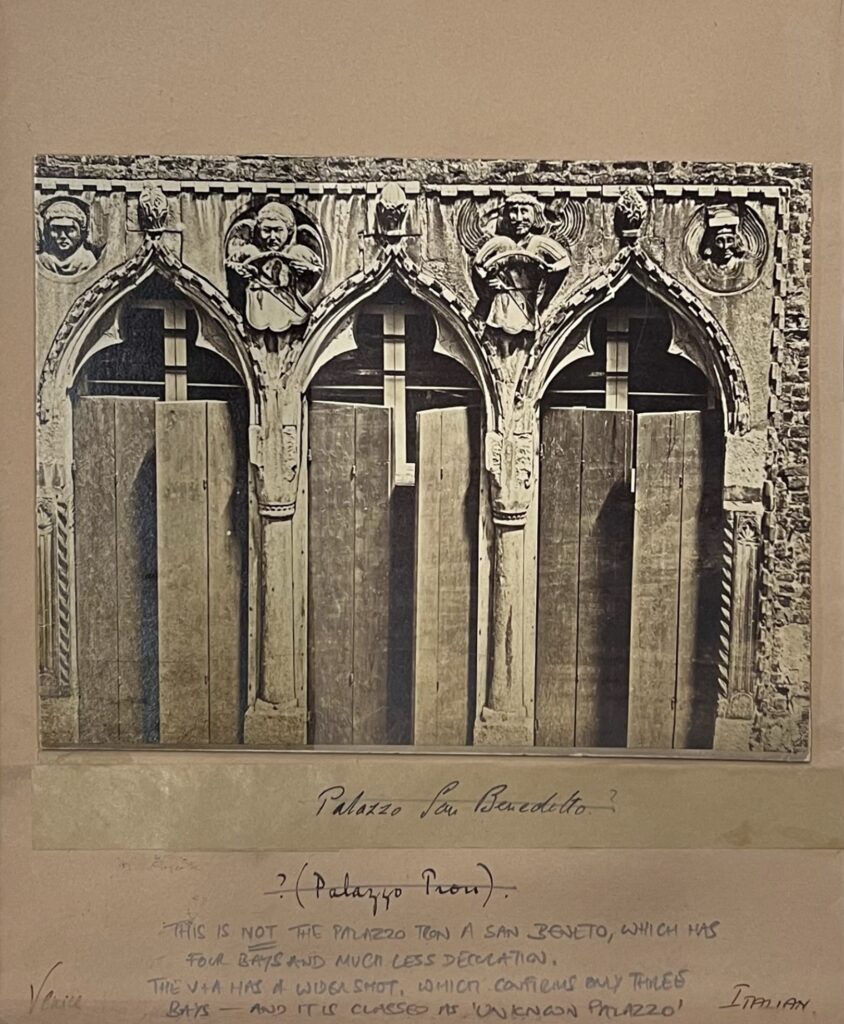

CON_B04390_F001_035

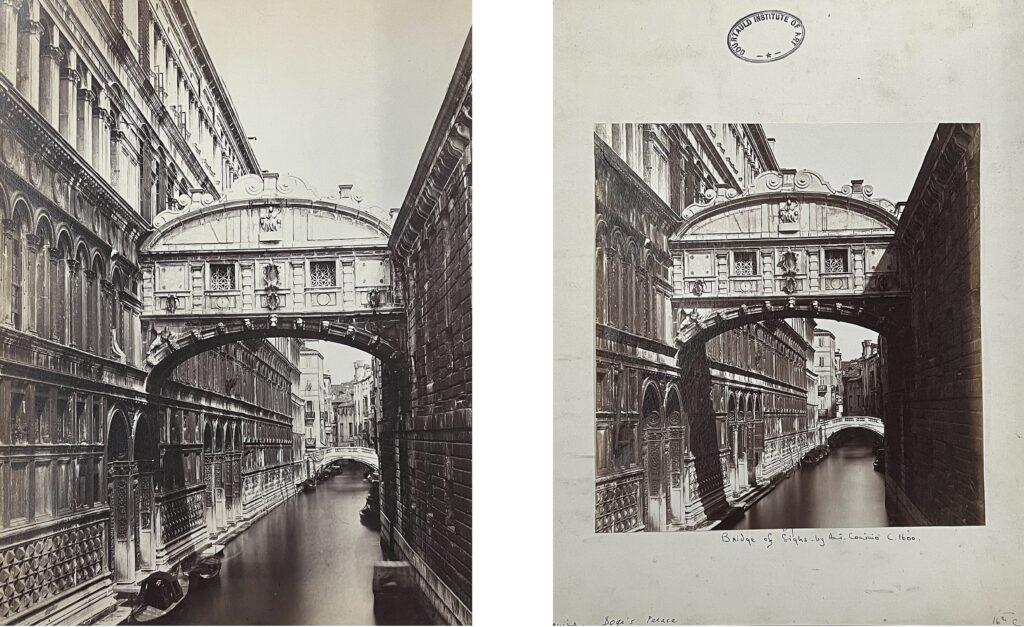

CON_B04390_F001_035 CON_B04390_F001_055

CON_B04390_F001_055