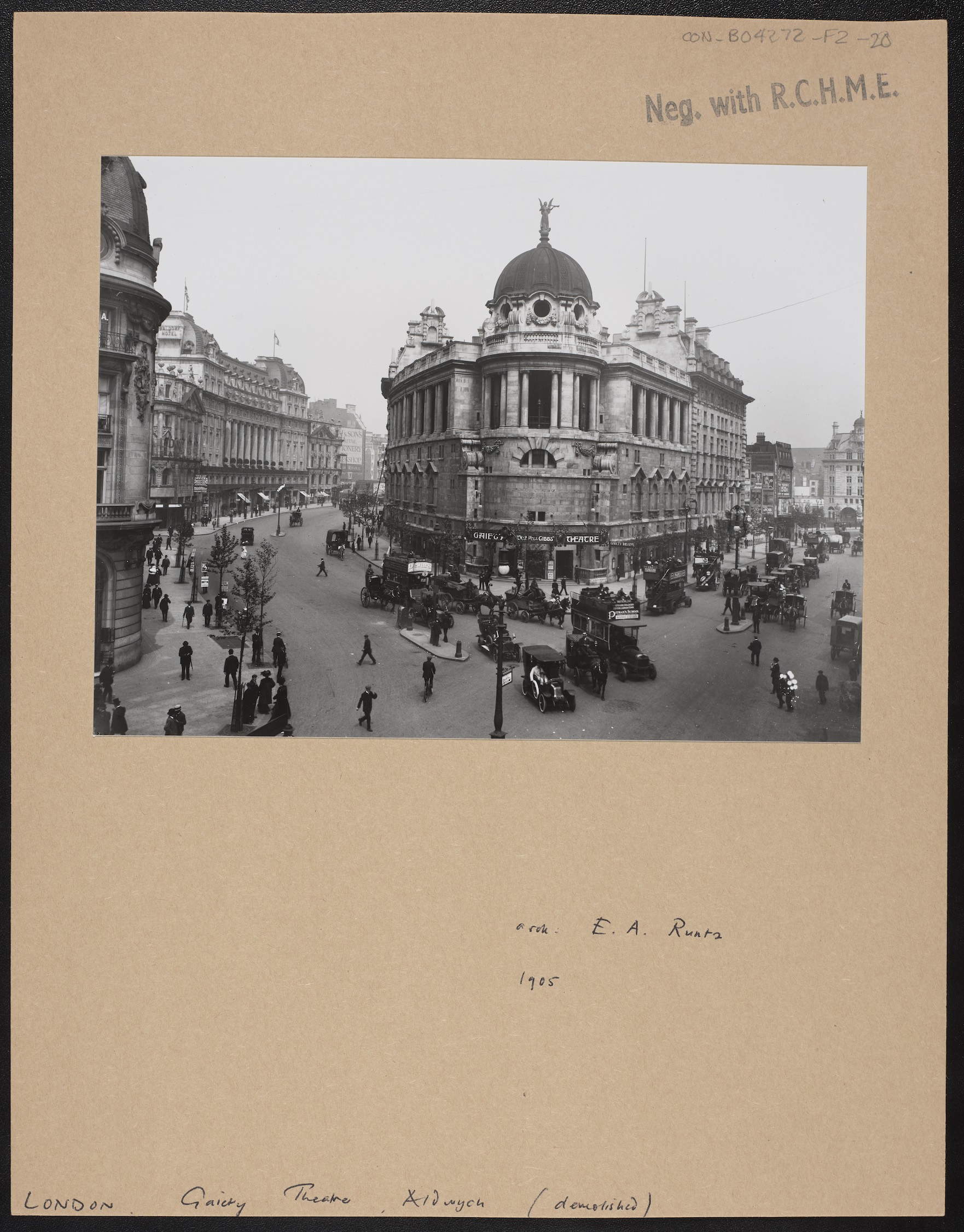

Over the past year and a half I’ve been a regular volunteer on the digitisation of the Conway Library at the Courtauld. From the start I loved the magic of the red box files and the anticipation of what was inside, what carefully catalogued items would I see this time. The range and scope were huge as we worked through the roller-shelving racks. Glass 1-7th Century, Metalwork 4th Century, 17th Century British needlework, Ceramics 16-18th Century, 13th Century Franco-Flemish psalters. And more psalters and yet more. I have also spent many sessions in the wonderful Kersting Collection sorting images and selecting master copies. When I started I was impressed by how much work had already been done by the volunteers and as I photographed the rows of labelled red boxes in February this year we were clearly in the home straight of this important project.

When the Conway Library went live online in April I was in Australia and remembered seeing pictures of buildings in Melbourne in the red boxes. I decided to check some of them out and see what they look like today.

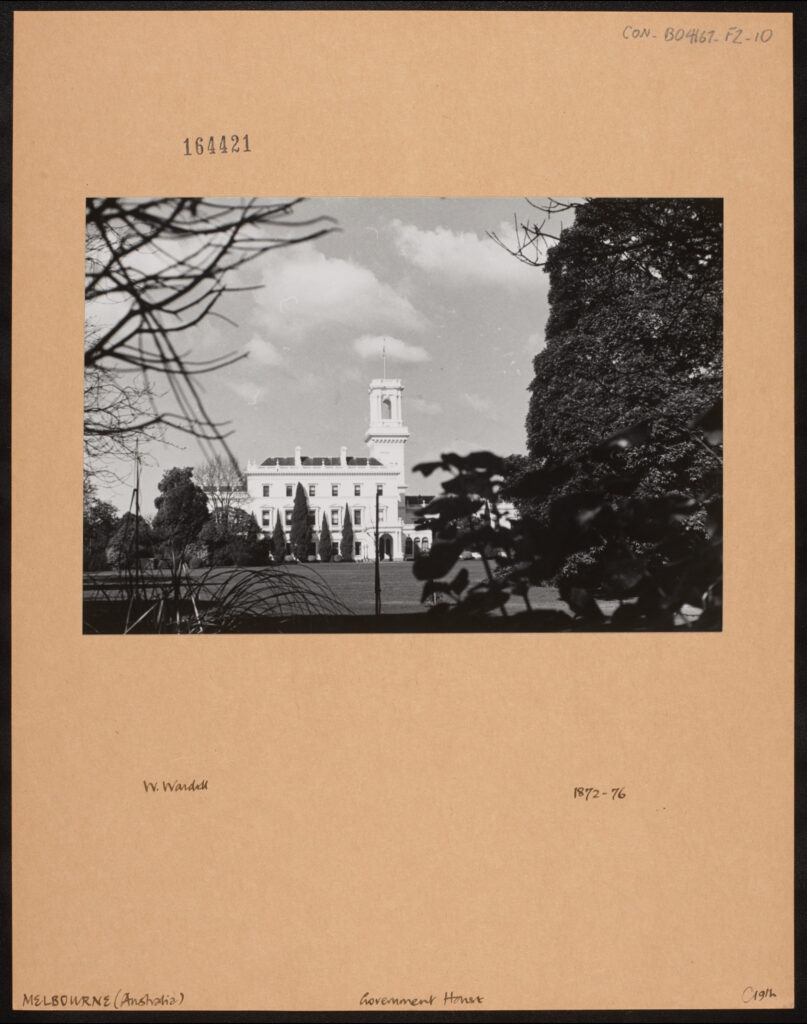

Government House in Melbourne was completed in 1876 as the official residence of the governor of Victoria. Modelled on Queen Victoria’s Osborne House, it is built on a grand scale with a tall belvedere tower and a state ballroom bigger than Buckingham Palace. From 1901 it became the residence of the Governor General of Australia until 1930 when Canberra became the seat of government. Then for three years it housed the Melbourne Girls’ School.

A black and white photograph mounted on card. There is a large white house in the centre of the composition with a four-walled, hollow tower extending upwards to the west of the building. The house has a darker roof and is three storeys high. Each storey is lined with windows, and there is an entranceway on the ground floor. The house is situated in the centre of a well-kept lawn and is lined with topiary. The image itself is framed by trees. [CON_B04167_F002_010 – AUSTRALIA: Melbourne, Government House. Architect: W. Wardell, 1872-76.]

Today it is the residence of Linda Dessau, 29th Governor of Victoria and the first woman in the role. There are a few days each year when you can visit Government House, but security is tight and I wasn’t able to get near for a picture.

A colour, digital photograph depicting a white stone, four-walled tower with yellow ensign flag placed above it. The roof is partially visible and is covered in a blue-grey tile. The tower is substantially ornamented, with patterned balustrades, architraves, and corinthian columns. [AUSTRALIA: Melbourne, Government House. Photographer: Christine Rodgers, 2023.]

A digital colour photograph of a large, light stone house enclosed behind a black, wrought iron fence. The lower storey of the house is an open loggia with large stone archways. The upper floor is lined with windows, most of which are decorated with simple stone pediments. The roof is decorated with blue-grey tile and surrounded by a light stone balustrade. [AUSTRALIA: Melbourne, Government House. Photographer: Christine Rodgers, 2023.]

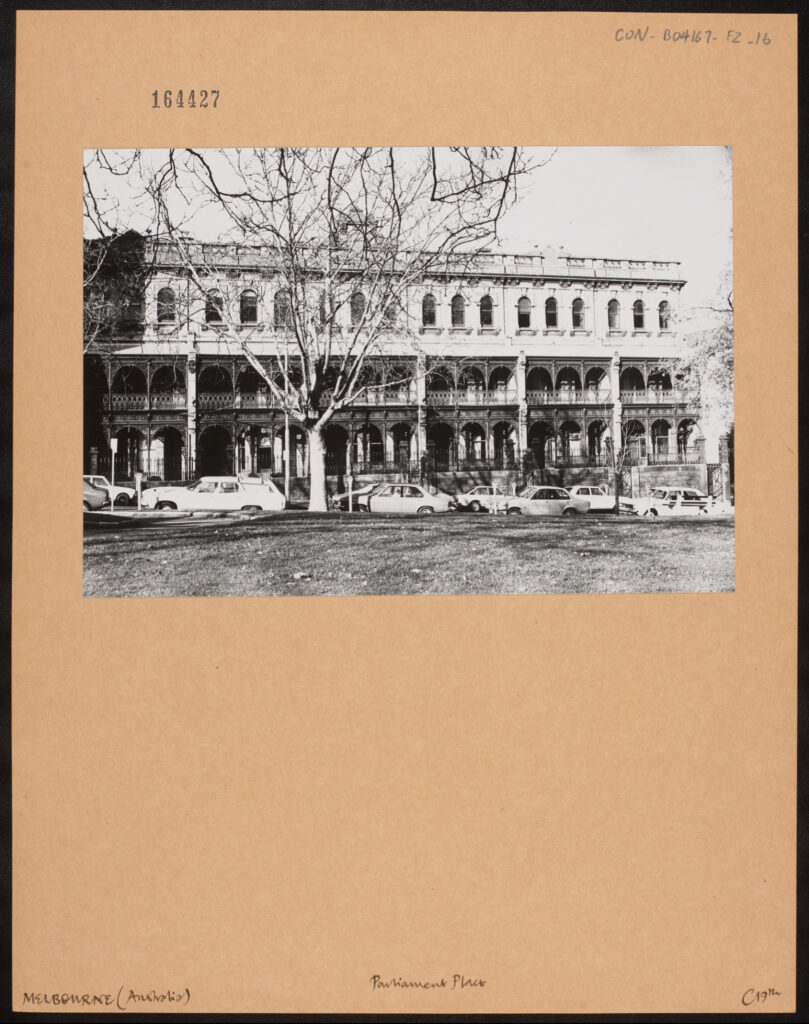

The buildings on Parliament Place remain exactly as they were, though the trees in the original photograph have matured so that the façade is obscured in part.

A black and white photograph mounted on card. The photograph depicts a three storey, neo-classical building. The building is constructed in a light-colour stone with wrought iron details. The ground and first floor are comprised of open loggias with wrought iron railings and archways. The second floor comprises of a row of windows each decorated with window hoods and decorative cornices. There is an ornamental clock on the roof which is mostly obscured by a tree. The building is surrounded by cars. [CON_B04167_F002_016 – AUSTRALIA: Melbourne, Parliament Place, 19th Century.]

A digital colour photograph depicting a three storey, neo-classical building. The ground and first floor are comprised of open loggias with pine green, wrought iron railings and archways. The second floor comprises of a row of windows, but this and the roof are mostly obscured by trees. The building is surrounded by a dark brick wall and further iron railings. [AUSTRALIA: Melbourne, Parliament Place. Photographer: Christine Rodgers, 2023.]

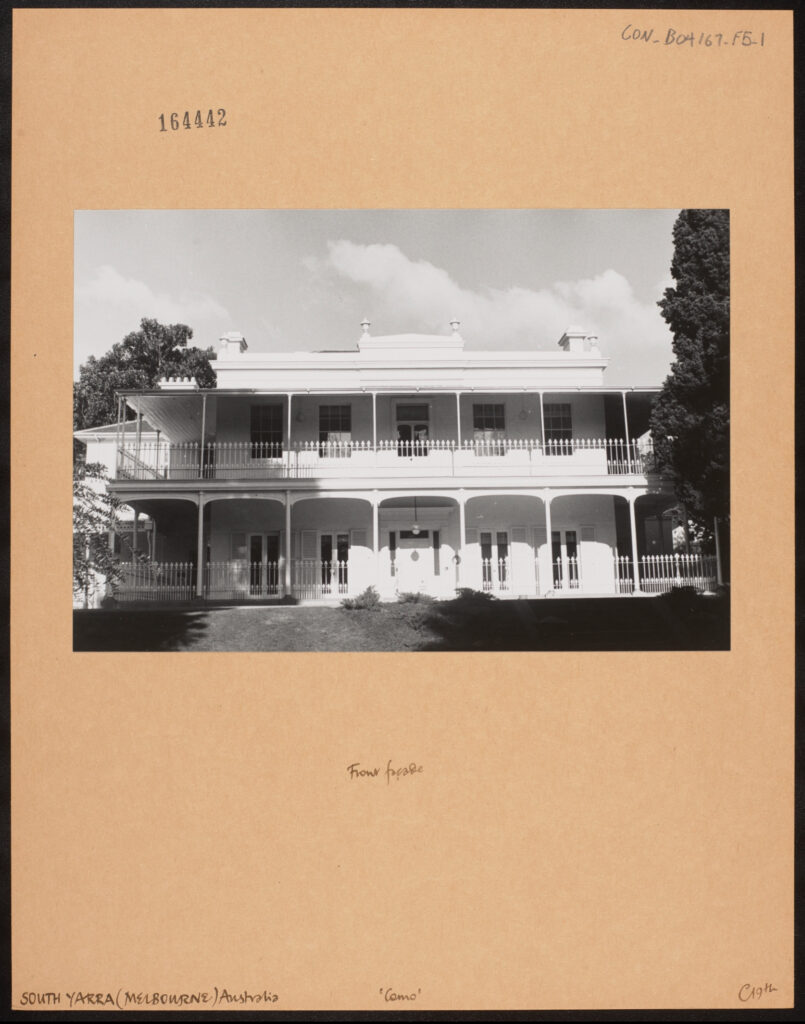

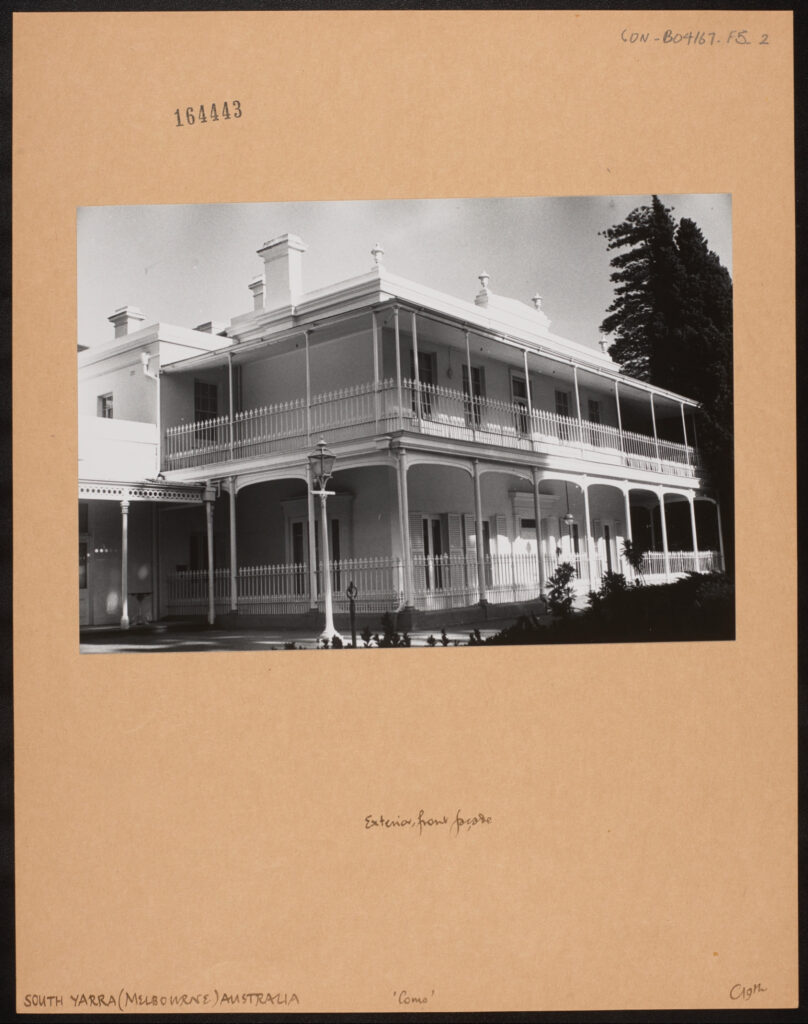

Built in 1847 the beautiful Como House in South Yarra is white with shaded verandahs and delicate ironwork – a style repeated on a much smaller scale on houses throughout Melbourne. Como was bought at auction in 1894 by Charles Armytage, a wealthy sheep farmer as a town house in the growing city to consolidate the family’s place in Melbourne society. He and his wife Caroline had ten children and lived at Como for almost a century. In 1959 it became the first property to be owned by the Australian National Trust and still contains all the Armytage family furniture and paintings.

A black and white photograph mounted on card. The photograph depicts a two storey, light-coloured building surrounded by trees. The house is simple, with both storeys lined with rows of long windows. Those on the ground floor are accompanied by white, wooden shutters. Two simple, open verandas wrap around both storeys with double-layered, white railings. The roof consists of a simple architrave, two chimneys to the east and west, and a simple pediment in the centre. Another room is visible on the first floor, towards the back of the house. [CON_B04167_F005_001 – AUSTRALIA: Melbourne, Como (Front Façade)]

A black and white photograph mounted on card. The photograph depicts a two storey, light-coloured building surrounded by trees, from the west. The house is simple, with both storeys lined with rows of long windows. Those on the ground floor are accompanied by white, wooden shutters. Two simple, open verandas wrap around both storeys with double-layered, white railings. The roof consists of a simple architrave with two chimneys towards the front of the building, and three to the back. To the bottom left of the composition, an open loggia is visible on the ground floor. There is a lawn to the front of the building, with a birdbath and garden lamp visible. [CON_B04167_F005_002 – AUSTRALIA: Melbourne, Como (Exterior Front Façade)]

A black and white photograph mounted on card. The photograph depicts a two storey, light-coloured building surrounded by trees, from the west. The house is simple, with both storeys lined with rows of long windows. Those on the ground floor are accompanied by white, wooden shutters. Two simple, open verandas wrap around both storeys with double-layered, white railings. The roof consists of a simple architrave with two chimneys towards the front of the building, and three to the back. To the bottom left of the composition, an open loggia is visible on the ground floor. There is a lawn to the front of the building, with a birdbath and garden lamp visible. [CON_B04167_F005_002 – AUSTRALIA: Melbourne, Como (Exterior Front Façade)]

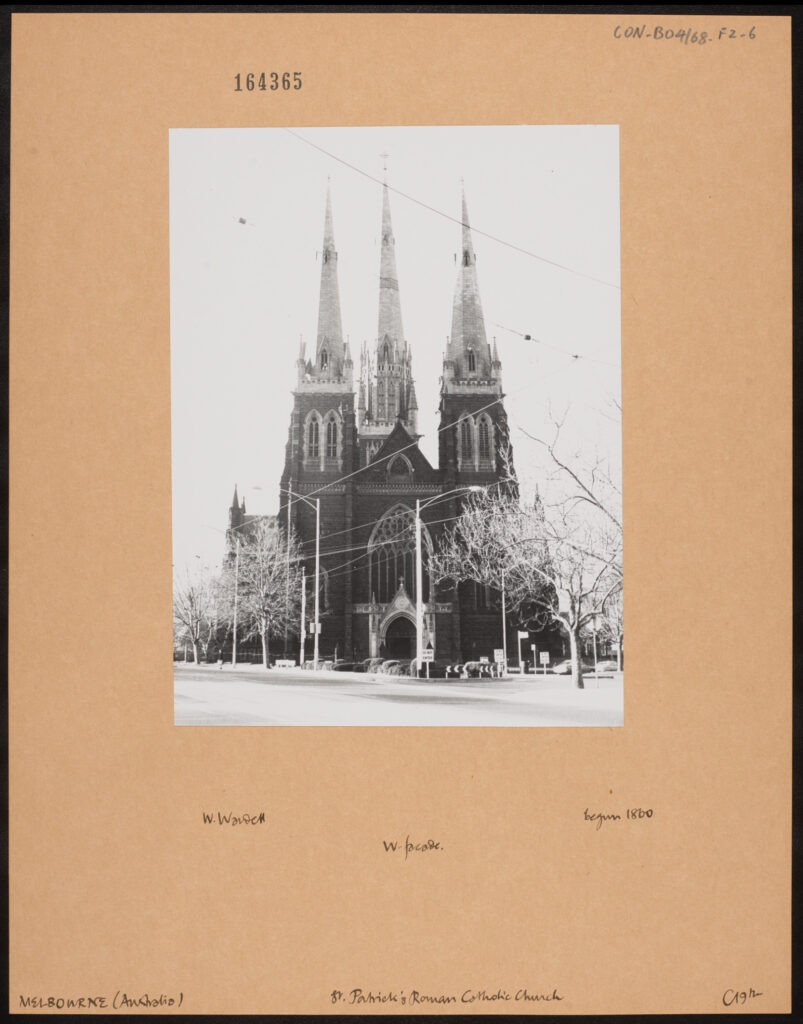

The site for St Patrick’s Cathedral was dedicated in 1851 but as this coincided with the Australian Gold Rush labour in Melbourne was in short supply and work did not commence until 1858. Construction was spread over many years, the spires being added in the 1920s and it was officially completed in 1939.

A black and white photograph mounted on card. The photograph depicts the western façade of a church. The building is built in dark brick, and the entrance is flanked by two towers. There is also a crossing tower towards the back of the church. The three spires are built of a light brick and extend into the sky. The towers are heavily ornamented with multiple smaller pinnacles as they meet their spires. The entrance on the ground floor is framed by a light stone arch with two ornamental towers on either side. A large, stained glass window extends upwards above the entrance, also ornamented with light stone. This central section culminates in a smaller pointed nave roof surrounded by a small balustrade. The church is surrounded by empty roads and bare-branched trees. [CON_B04168_F002_006 – AUSTRALIA: Melbourne, St. Patrick’s Roman Catholic Church, Western Façade. Architect: W. Wardell, begun 1860.]

It looks today very much as in the Conway Library pictures. However the congregation now is mainly Chinese Catholics who live in this part of the city.

A digital colour photograph depicting a large church. The church is built in dark brown brick, and the entrance is flanked by two towers. The three spires are built of a light, tan stone and extend into the sky. The towers are heavily ornamented with multiple smaller pinnacles as they meet their spires. The entrance on the ground floor is framed by a similar, tan stone arch with two ornamental towers on either side. A large, stained glass window extends upwards above the entrance, also ornamented with tan stone. This central section culminates in a smaller pointed nave roof surrounded by a small, tan stone balustrade. [AUSTRALIA: Melbourne, St. Patrick’s Roman Catholic Church. Photographer: Christine Rodgers, 2023.]

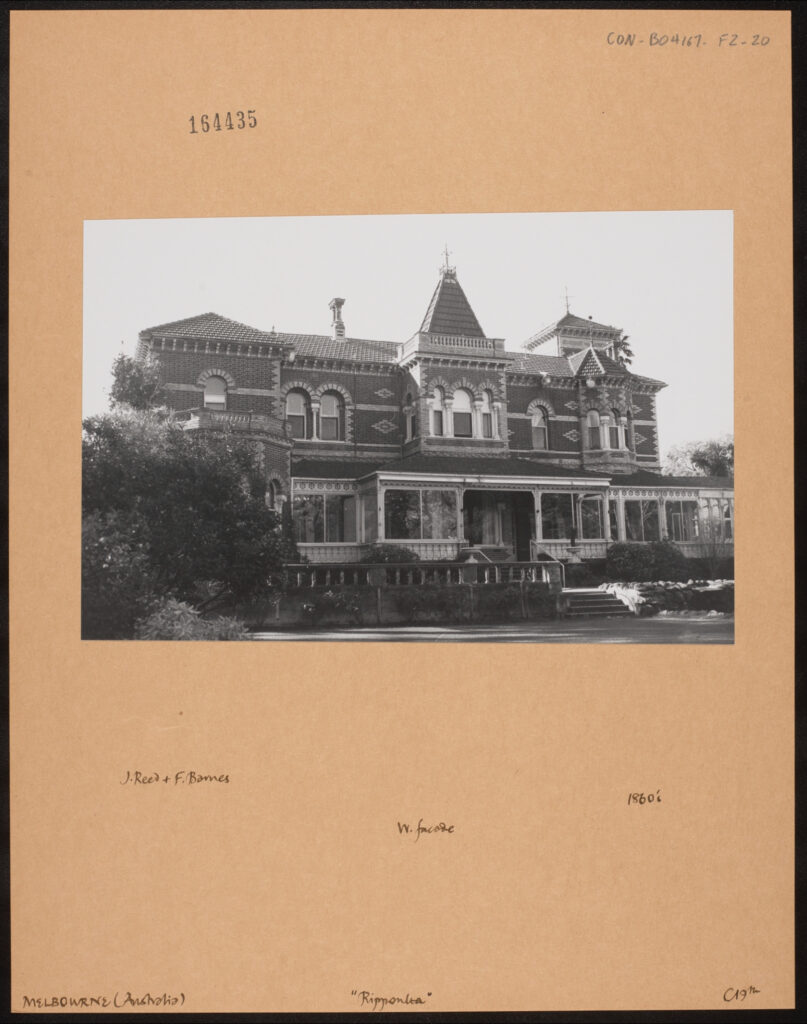

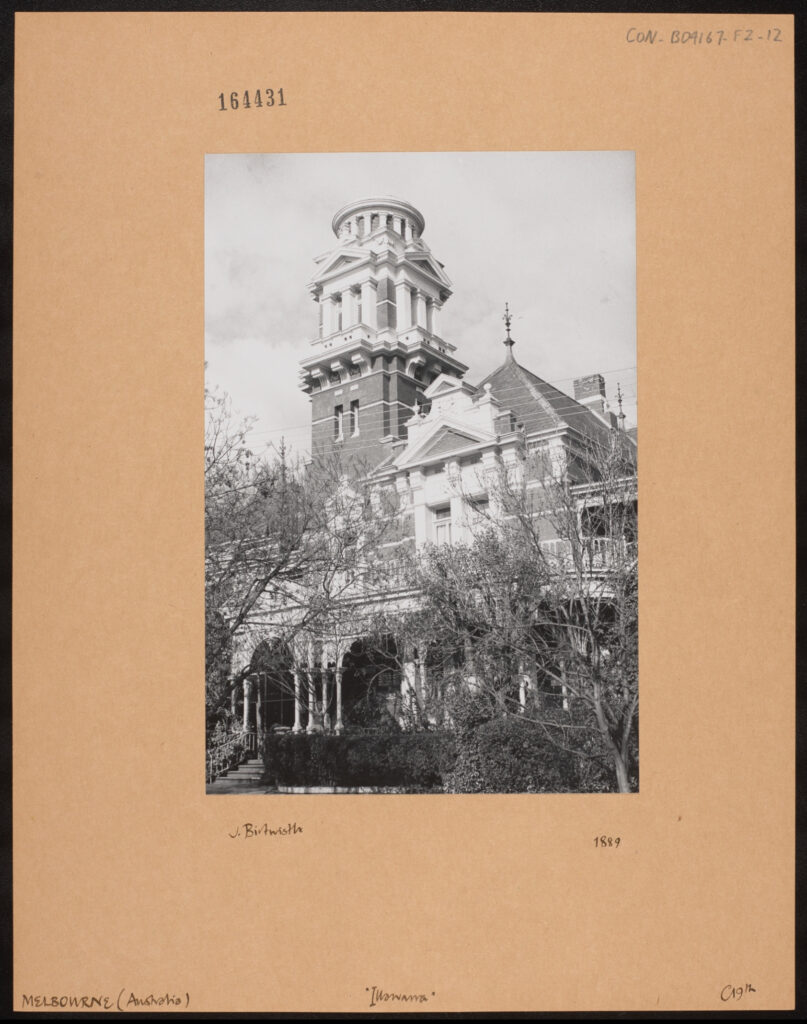

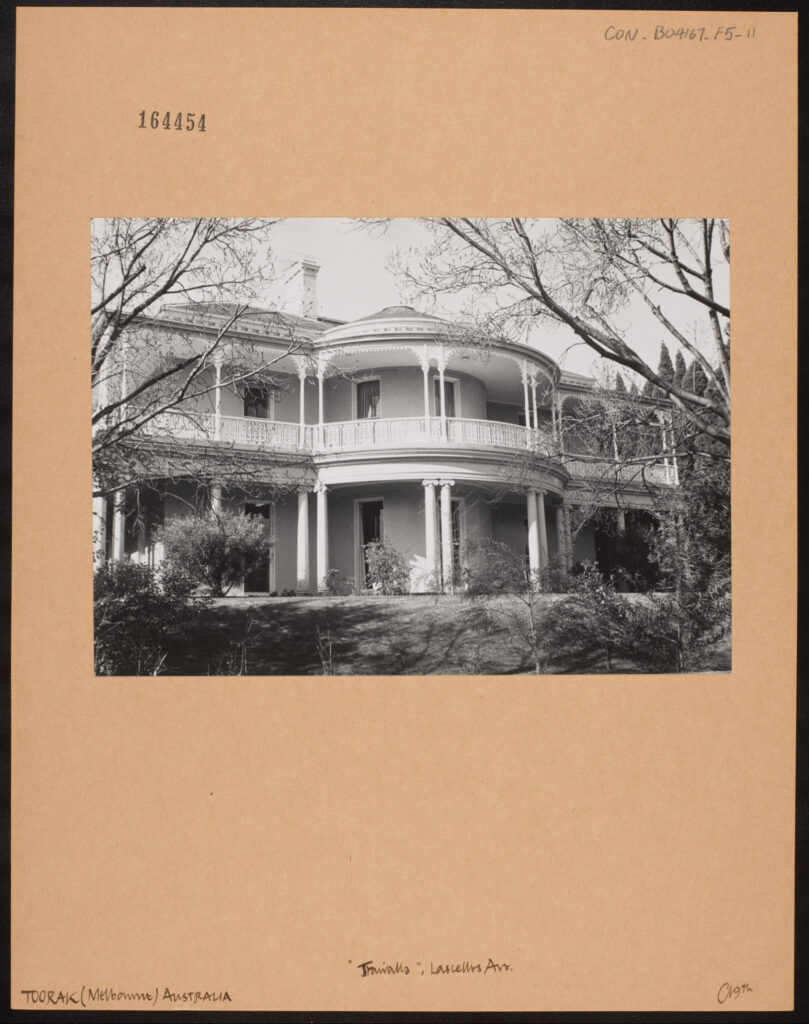

Other substantial Melbourne houses among the Conway Library pictures are Rippon Lea, Illawarra House, and Toorak House.

A black and white photograph mounted on card. The photograph depicts a large, two storey building surrounded by small trees. The building has been constructed using dark bricks with white ornamentation, including triangular patterns on the walls of the first floor and striped window hoods. There are dormers on the first floor, one partially obscured on the western side. Two of the three dormers have a square bay window, the third is curved. The roof is tiled and there is a visible chimney as well as a large, pyramidal tower atop the central dorme, which is surrounded by a square balustrade. The ground floor is comprised of an enclosed loggia with large windows. To the east of the building, there is an octagonal room which juts out of the front façade. The building is surrounded by a stone wall. [CON_B04167_F002_020 – AUSTRALIA: Melbourne, Ripponlea. Architects: J. Reed and F. Barnes, 1860s.]

A black and white photograph mounted on card. The photograph depicts a large house, at least three storeys high. The building is comprised of an open loggia or walkway on the ground floor and a dormer on the first floor. The dormer is decorated with pediments and columns. There is a four-walled tower behind, which culminates in a ring of ionic columns and a flat, elliptical roof. The house’s brickwork is varied, with much of the architectural details highlighted with light stone. The house is cloaked in hedges and trees with a small set of stairs leading to the house visible to the left of the photograph. [CON_B04167_F002_012 – AUSTRALIA: Melbourne, Illawarra House. Architect: J. Birtwistle, 1889.]

A black and white photograph mounted on card. The photograph depicts a large, two storey building with a substantial rotunda in the centre of the façade. The ground floor is comprised of an open loggia which runs along the façade, wrapping around the rotunda. The loggia is decorated with ionic columns. The first floor is comprised of an open veranda, the railings of which appear to be a white wrought iron. The walls of the building are plain, and covered in rows of tall windows. The roof is partially obscured, but a large, narrow chimney is visible. The building is set amongst many trees and a well-kept lawn. [CON_B04167_F005_011 – AUSTRALIA: Melbourne, Toorak House (Lascelles Avenue)]

Christine Rodgers

Digitisation Volunteer