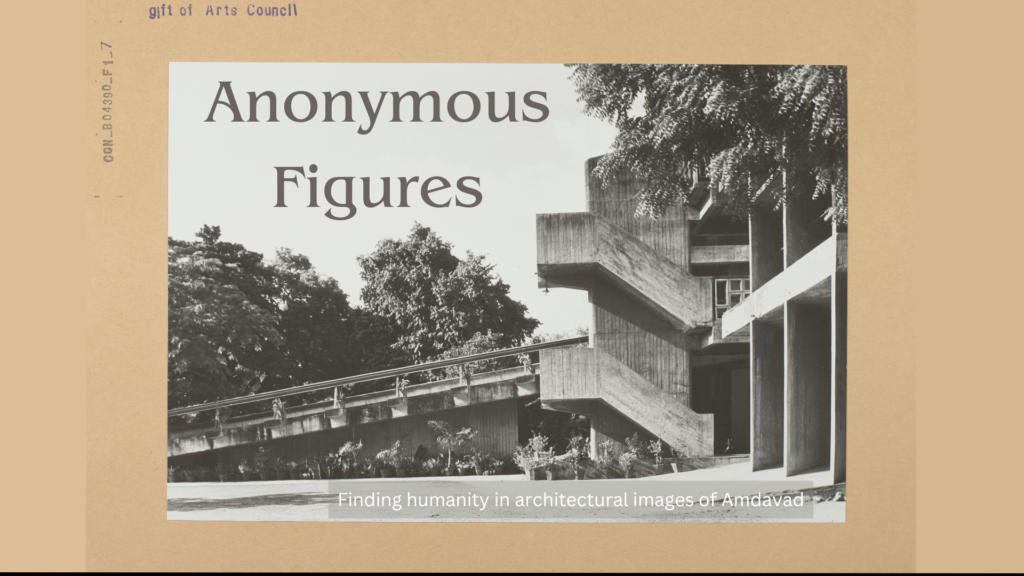

Disclaimer – This collection is a work of fiction. Any resemblance to anyone in real life is completely coincidental.

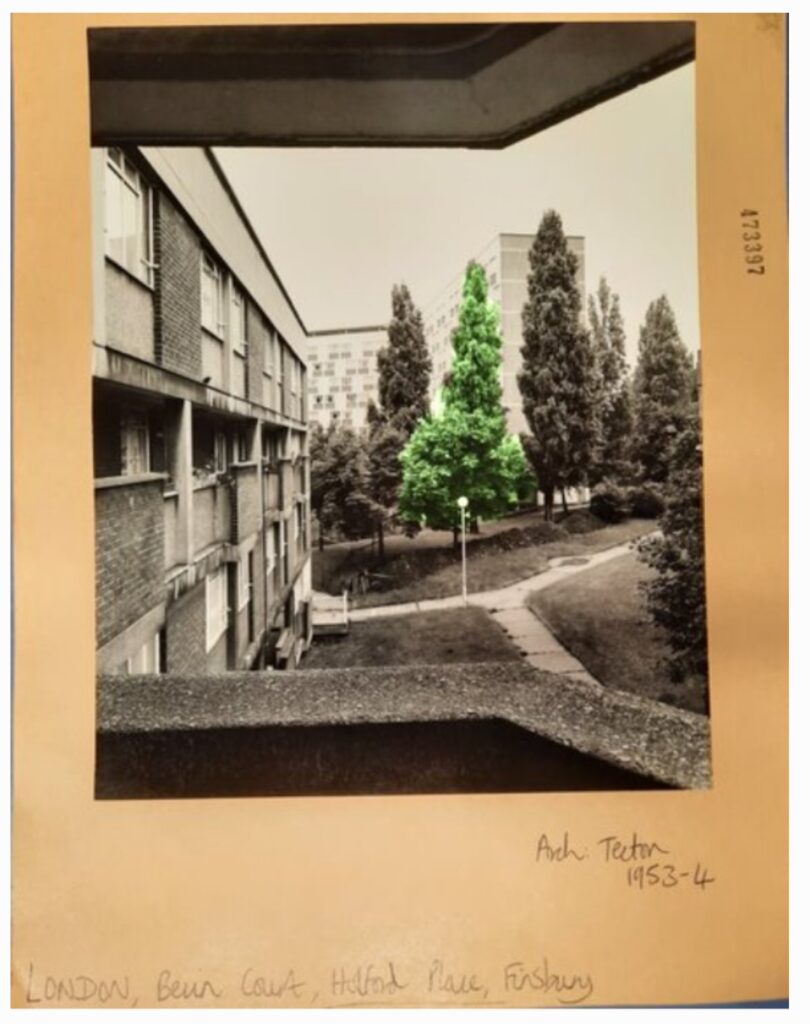

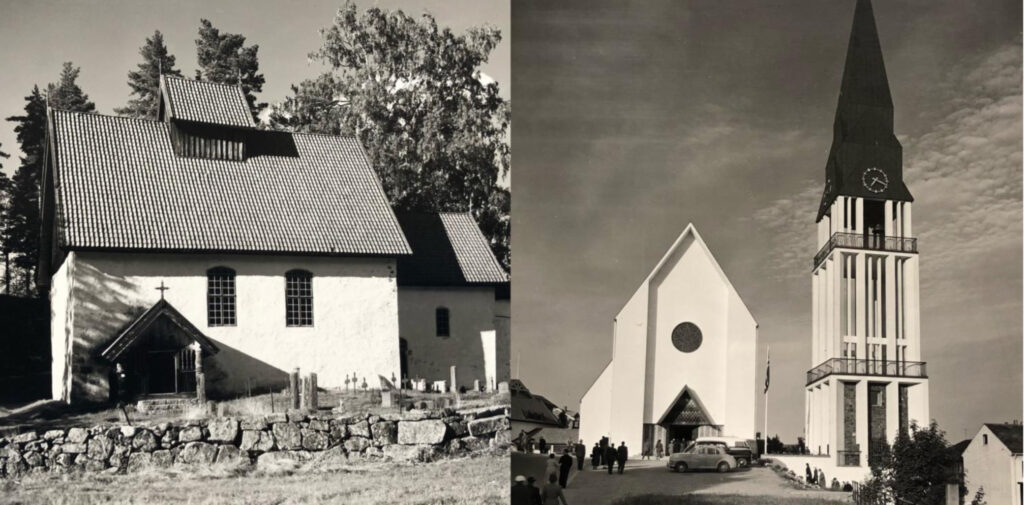

Story One – scratching against the stone

The birds sang with the sound of the morning light, the sound caressing each and every particle of matter until it was as soft as the hum in the air. The world was still, just for a moment, as the trees swayed and staggered, as the hay found itself tall and waving. Spring rang bright and clear, casting them all in a sea of colour and joy.

It wasn’t until the evening that it all went away, that the sun grew tired and withered away against the evening sky, below the horizon, to grant new people the same light that blessed them. The evenings ran cool, and the birds slowed to a gentle, methodical hum.

And then the scratching began.

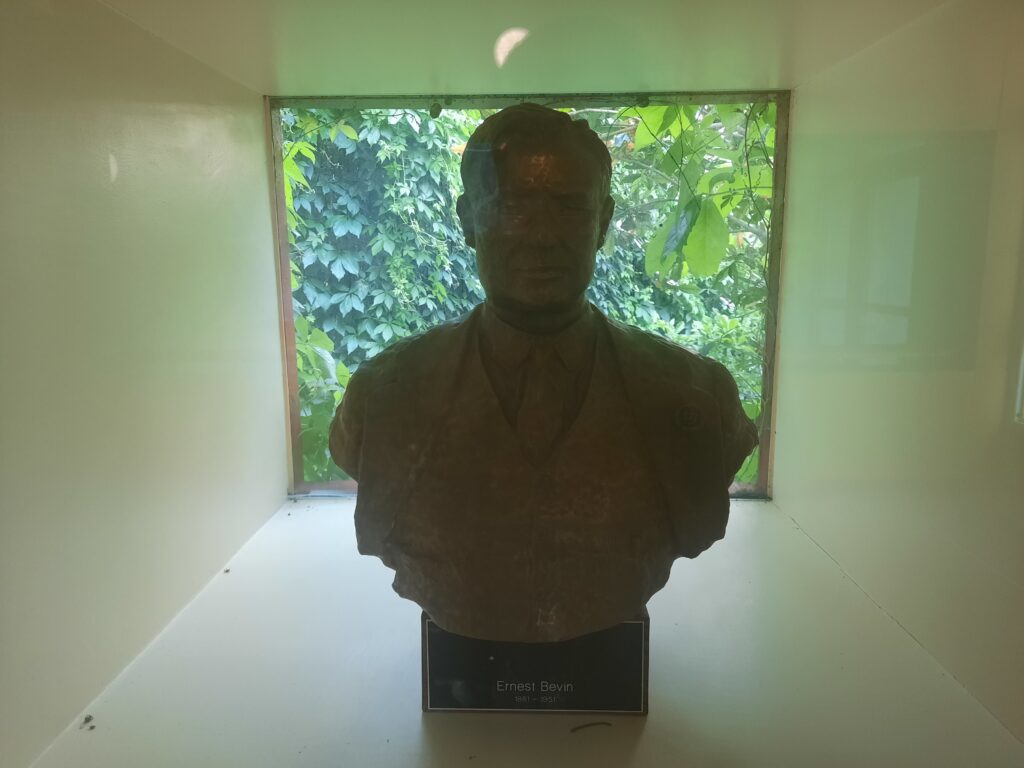

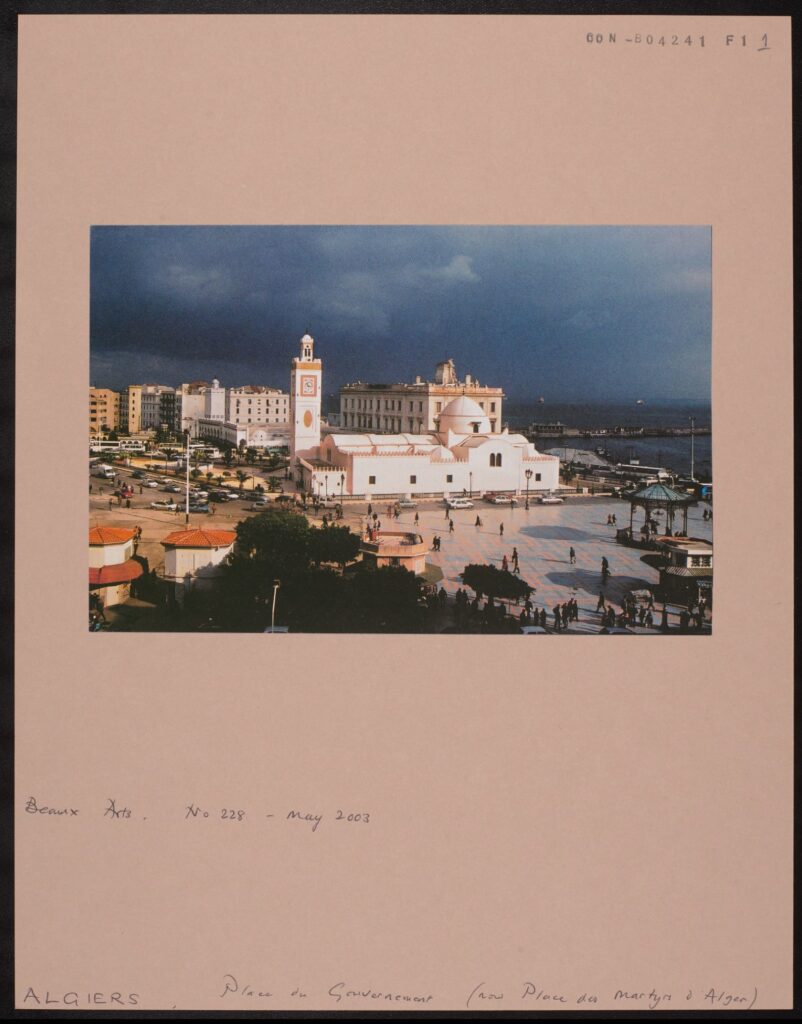

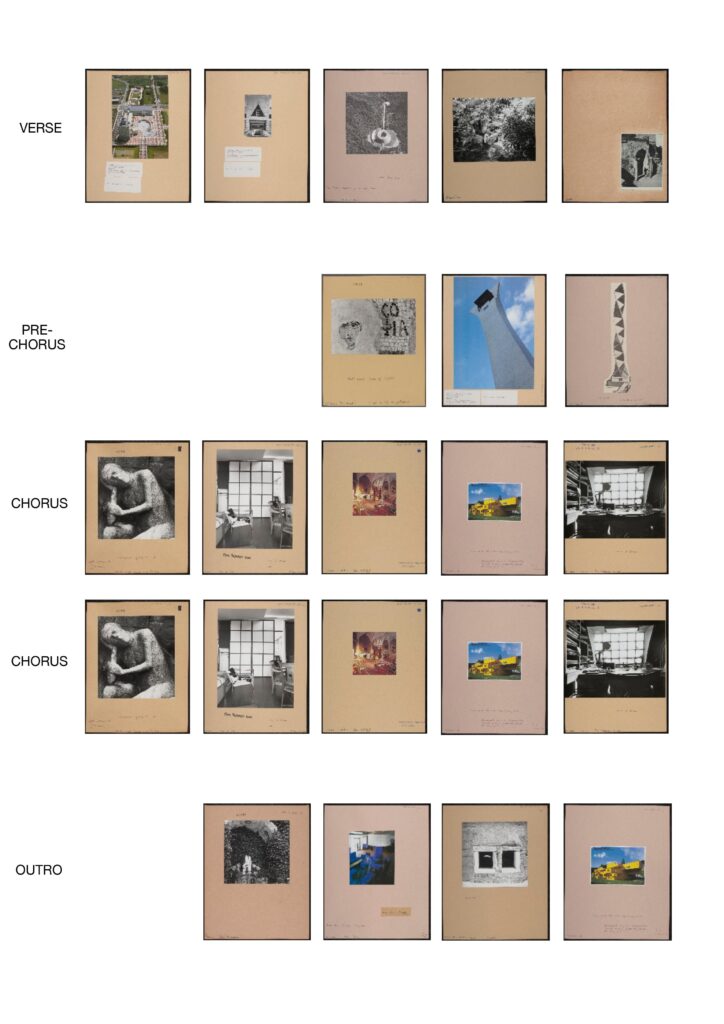

The birds screech to a halt, almost as if to sit and listen to that same etching, tearing away at the mountaintop until they saw the pictures clear and the ash and debris crumbled along the floor, ready to be trampled on so it could be at one with the floor. The stone cried, not at the act or the pieces of itself crushed against the ground. It cried at the art, the pieces of the world they couldn’t see, brought to it, carved into its flesh and bones. A bull, a bear, mammoths all cobbled together on one slab of rock.

But why? Why had they felt the need to make their mark? Had boredom struck, with no way out other than to occupy themselves? Was this the work of a great mastermind only years before their time? Was this the beginning of genius? Whatever it had been, they carved their name in the shadows, destined to be remembered.

The bird began again the moment the scratching had stopped, humming their peace along the silence, joining their call around that great mastermind, the painter without a face or name, the only hum in the still, the first visitor in thousands of years.

Over the years, they returned every now and again to add to the adventures. They drew hand-carved spears and epic wins against red gazelles and hartebeest, of people and their stories, until one day, it all stopped. He never returned again. The birds sang uninterrupted, and the carvings remained untouched, preserved just as they were while the world crumbled away and built upon ruins and ruins.

Life, empires, and people had flittered from life to memory, but what remained, what always remained, was the art.

It wasn’t found until centuries later, eager archaeologists with nothing in their minds besides the hope for a new discovery. The strangers entered; eyes widened in admiration at the detail, the stories of hope, of loss, of food and of friends. They spoke to one another in loud, inconsiderate, ungrateful voices, only marvelling at what was not their own.

It wasn’t until only one remained that the cave found its voice to be heard; the birds sang softly, the sand shifted around them as the wind picked up, and finally, after the myriad of peace and light, the scratching began.

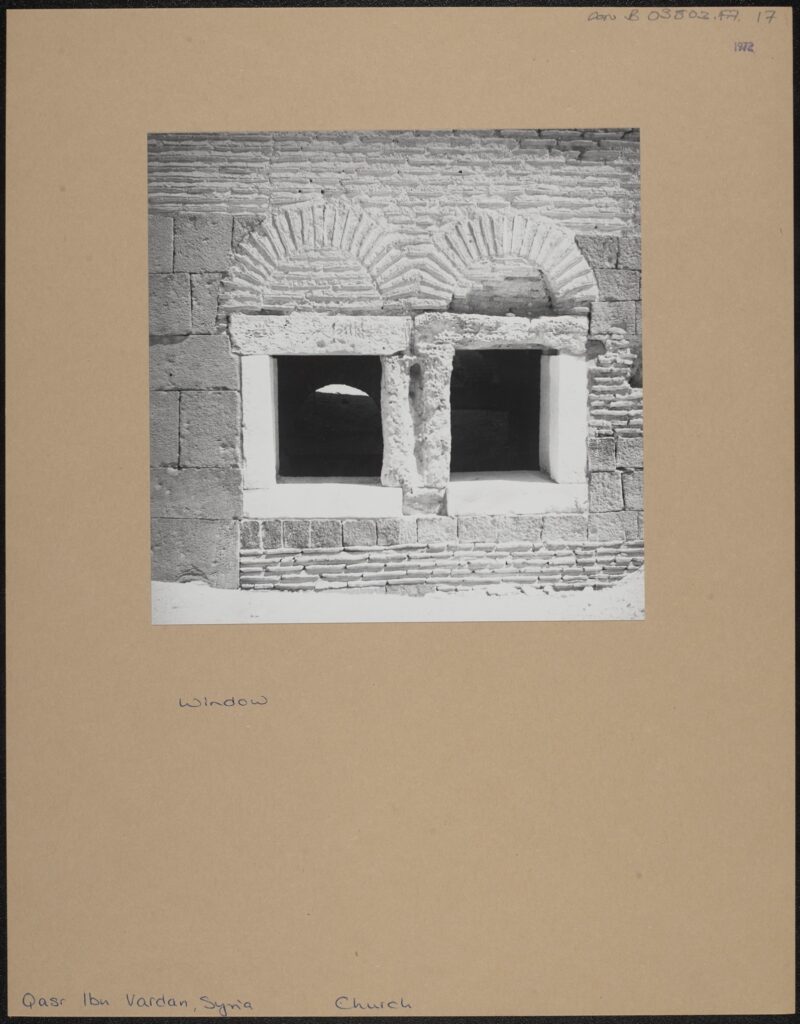

A black and white photograph mounted on card of two people investigating various prehistoric rock carvings on a large rock surface. Some carvings appear to be horses or livestock. [CON_B00005_F05_02, Near Tiaret (Algeria), Prehistoric rock carvings at Ket Bou Bekr.]

*

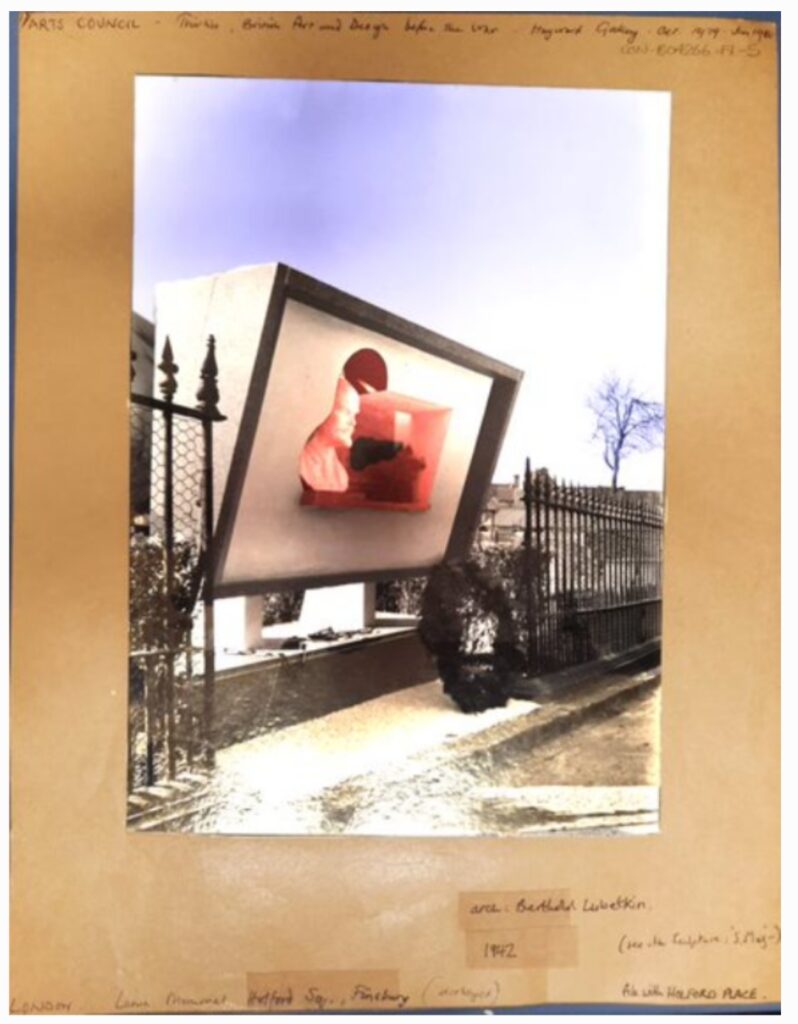

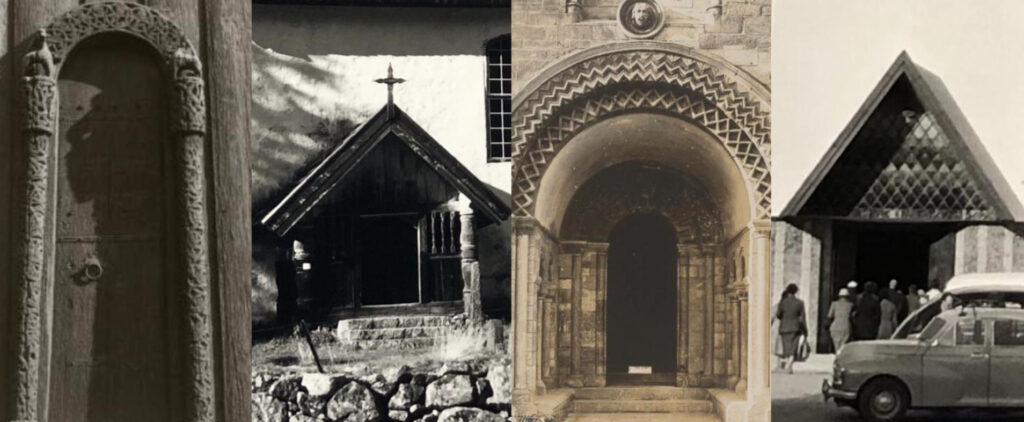

Story Two – the circus had come.

The circus had come.

It was all they heard on that Tuesday morning; that the circus had come, to spring for joy and watch over the kids bound to cause a ruckus among the great stone walls. Workers, baking in the golden Algerian sun, whispered about it in low voices. The children jumped whenever they remembered, recalling moments of watching horses barrel around one another. One, the child of a wealthy family, told the same story: of touching the horses, the stone tracks under their feet.

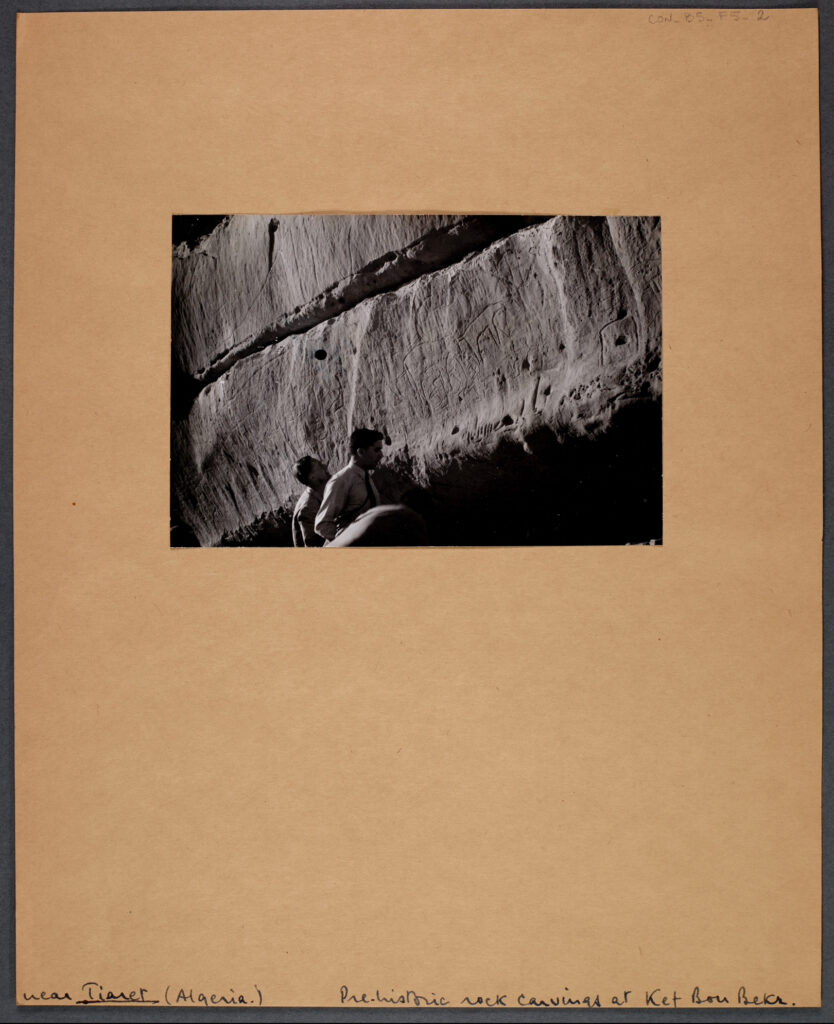

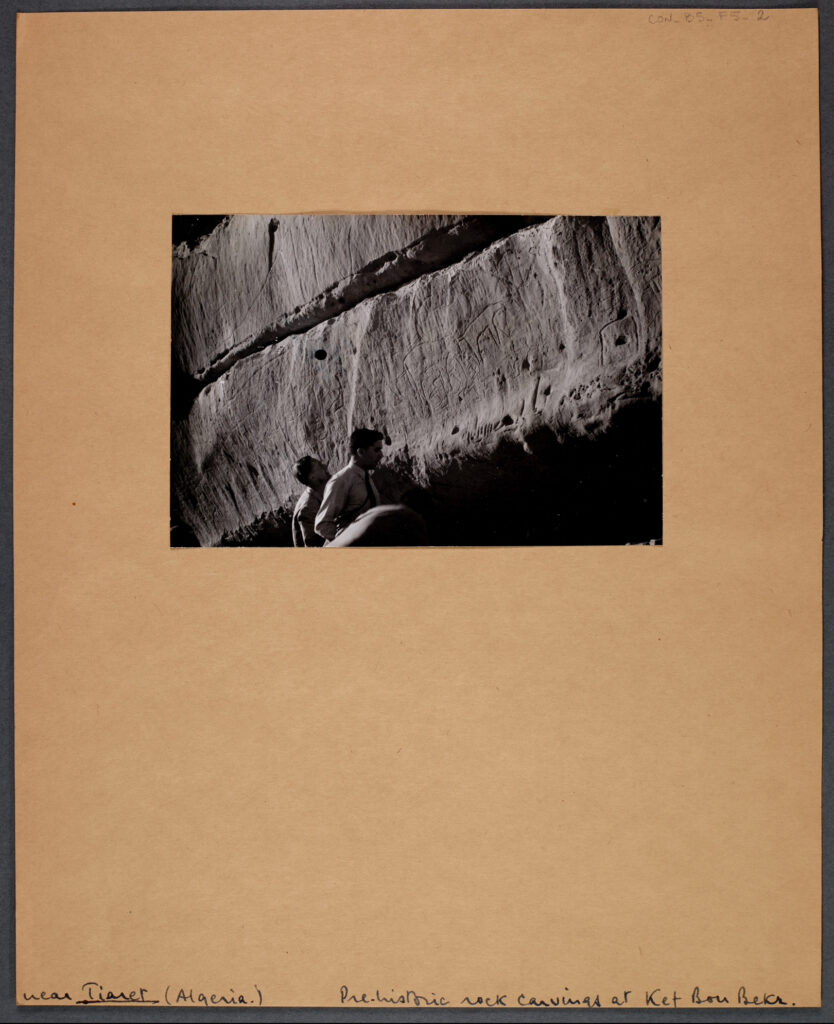

Technically the circus was always there; the building stood still among the forum, fixed in stone and sand, the workers walked among them so often they could practically have their names written on the walls. But the shows, they came on the off-day, sudden. Word spread quickly around Timgad, so the second a whisper had been sung, the cannon had been fired, and everyone knew.

Deep in the suburbs, in houses made of stone, a boy lingered. He hid behind a partition between one room and the other, away from a woman who seemed familiarly serious. He crept along despite it, out of sight, travelling low and slow until he reached the door. His hand touched the handle, but the moment he had been beginning to move, she called his name.

His eyes widened, turning on the heel of his foot to grin at his mother. “Yes?” she asked as she gave a reluctant smile. She gave her usual speech: be back before sundown, stay with your friends, stay away from the heat of the crowds until he could find her, and take her hand. It was only when she pressed a gentle kiss against his temple, caressing the soft skin on his cheek, that she finally herded him out of the door with a small straw basket with as much urgency as the situation needed.

The sun was climbing in and onto them, filling them with a yearning for shade, cold wind, and fresh water. There was nothing in that crowd besides desperation, hopefulness, and a boy running through the cluster with a list of things to achieve. As he sprinted, the air moved, parting to give him the space to soar. Dust ricocheted from the floor, spraying everyone in the vicinity and leaving behind him cries of annoyance.

“SORRY!” he laughed behind him before sprinting round a corner where he knew he could buy something to sustain him. He turned another corner, stopping directly in his tracks when he realised what it was.

The queue for pine nuts stretched across the street, ebbing and flowing as the crowd grew stronger, fiercer, and increasingly impatient. Would there be any nuts left for him? Would the crowd take this right directly from his fingertips?

There was no choice but to run or wait, so he waited. The crowd moved quickly, but not quick enough. He would miss the beginning if he stayed, have to stay in the highest seats, sit with those out of his social grade, and bring shame to his family by associating with the sort. His family could be pushed from their home, the pinnacle of pain and suffering, all for pine nuts.

But the queue was moving quickly. People left on their own accord, moaning in frustration for the time wasted; the poor man at the booth scooped as quickly as he could. The boy bounced on his feet to bid the very thing that lingered on top of him, waiting as patiently as his impatience would take him. Despite it, he got to the front of the queue with time to spare – the first horn hadn’t even been blown yet.

The vendor was an elderly gentleman with crooked and blackened teeth and eyes full of joy and light. They made him seem gentle, generous, giving. They exchanged pleasantries as the crowd behind them gathered closer. The vendor scooped a generous amount of nuts into his basket and then a little more for good measure. He herded him away, just as his mother did, knowing his reaction before it was given.

Was the desperation that clear?

He began to run again, just around the corner of the stone houses, temporarily shielded by the shade and slowing down to gauge his surroundings. It was a left and then a right again. He could see the amphitheatre in the distance, a short way away. The first calling horn had yet to blow. He could only wish for miracles, they seldom came to light, but this was astonishing; was he going to be early?

When he began running again, at full speed, following the crowds that had similar journeys from similar houses, he swerved against the passing people to each and every corner, shouting his hellos at anyone who could listen. He turned the last corner suddenly and then–

His face suddenly touched the floor, lips kissing the gravel, chin scraped against the rough stone. He groaned, hoping there wouldn’t be blood against his white toga. “NO WAY!” he heard, head snapping to the perpetrator of his assault. His mouth broke out in a grin immediately, embracing his friend and looking for his other, who had usually been by their side. His friend’s blue eyes shone back at his own, almost closed from the widening grin.

“Where is Ixhil?!”

“We can’t find him! We think he’s at home! He doesn’t know the circus is here!” His friend stood, looking strangely serious, picking up the boy’s sealed basket of nuts. “Let’s go!”

They turned back just as the first of the three bells rang, sprinting faster to catch up to their crowd. Time was not on their side, the sun would dip in a few hours, and he would need to be home. They finally found the house, standing before a large, brown door and disturbing the world behind with furious nocks.

“IXHIL! THE CIR—”

The door opened before they could finish, and Ixhil, a taller boy with dark skin and a distinctively furrowed brow, shoved open the door with a passionate curiosity, making the two before he stumbled forward. The horn’s call had told all the village people all they needed to hear. Ixhil had dressed and had been ready to leave with them before the first word had even been spoken.

Their footsteps lined in sync as the second horn bellowed through the town, calling freely at the people to come forward, to enter the only place they could remain themselves. Stalls were left empty, houses vacant with doors wide-open – smells of bread beaming from kitchens.

The crowd thickened like corn starch to gravy, leaving no place to run, turn back or hide without the risk of being heavily trampled. They turned their last corner, eyes widening with wonder as the building’s shade consumed them.

It had not been anything particularly new or strange. In fact, the theatre had been crumbling since the dawn of time, but that didn’t matter. With the moaning walls and creaking Corinthian columns, its dereliction meant this could be their final show, draped within her walls. The idea made the boy, his friend, and Ixhil sad. To them, it was larger than life, spreading across their entire world and becoming the sky. The theatre was not big by any means, especially not in comparison to the others he’d seen in Rome or in France, but it was theirs: Timgad’s very own.

They looked at one another once they’d found their seats, eating from the open basket of pine nuts, waiting for the third and final horn to ring. They laughed, whispering among the people about anything and everything, side by side, heated by the sun against their skin. Soon they’d be golden and wrinkled, frail and old. They all knew time was a fickle thing – never on their side, but today, they laughed. They settled into silence just as the last horn rang through their small, small town.

Hundreds of years later, after decades of myths and legends about a town hidden under Saharan sands, the laughter remained. Even when people found the bones hidden, bodies clinging to one another, they shook with mellow, joyful laughter.

A black and white photograph mounted on card of the ruins of a stone colonnade, part of the Theatre at Timgad, with a section of curved seating visible behind. Beyond the ruins, a hill and distant mountains are visible. The environment is arid and open, the sky bright and clear. [CON_B00005_F012_023, Ruins of the Theatre at Thamugadi (Timgad) in Algiers, Algeria, 1904, No. 85. Hirth’s Formenschatz Practical Art Gallery.]

*

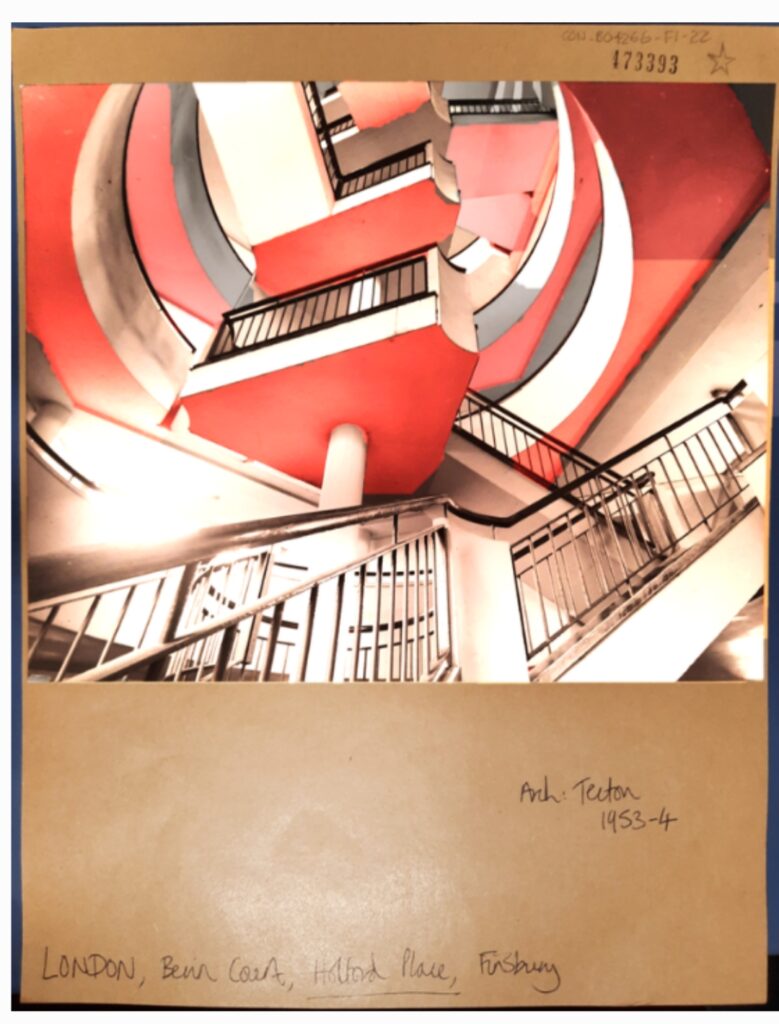

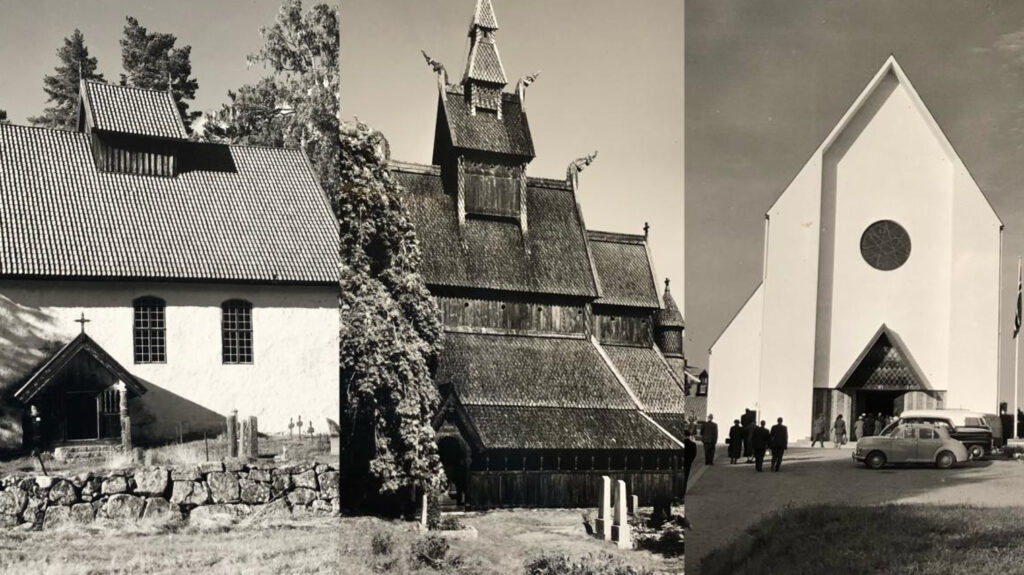

Story Three – today was different.

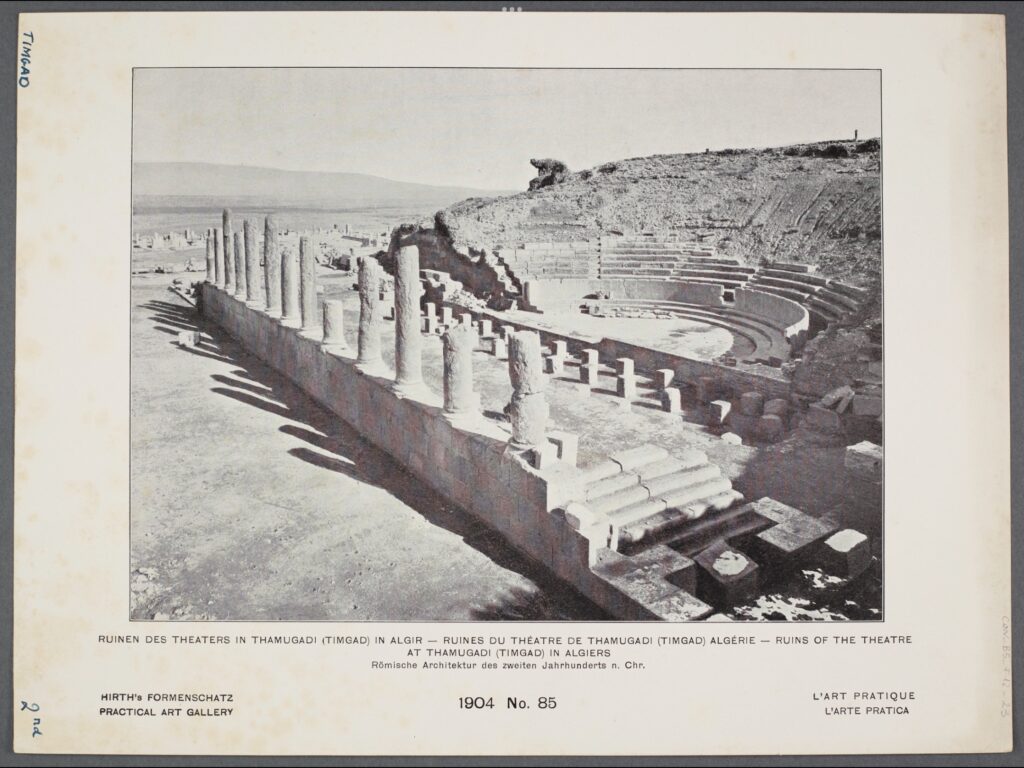

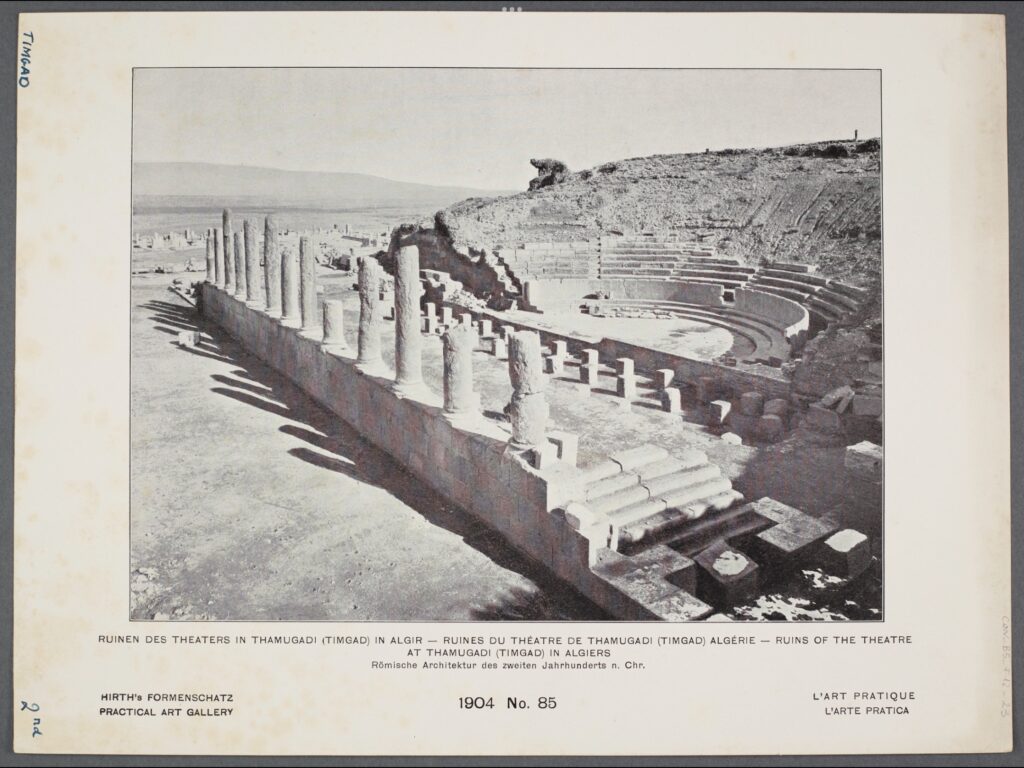

In the middle of the Kasbah, at the very top of the mountain the citadel had been built upon, surrounded by growing trees and other grand, unfamiliar houses, lay a villa fit for royalty. Royalty, however, did not own the three substantial floors, the dozen bedrooms or the twisted pillars that held it all together. It wasn’t royalty who embellished the ceilings and the staircases with gold or who etched names and initials into the same wall to scream ‘I EXIST!!!’ at the top of their lungs into every part of their quiet presence inside the house. It had been a simple family that resided there instead, filled with everything that peaceful simplicity needed; grateful people and eternal love.

In the middle of the square, an open, flower-spun courtyard, under the hot summer sun and within the confines of four tall walls, the youngest of the family was sat practising what could only be known as a… personal piece. Yes, it was offkey, and yes, it may have been the only noise in the house keeping the sun in the sky and the world awake. But in terms of saving grace, it was not entirely awful to her. She winced as the string of her mandolin almost snapped, biting the tips of her fingers, adding salt to the already piercing wound. She was playing so her father would come back to music; she was playing for joy.

“Can you stop that racket? You’re giving me a headache—” A boy, the oldest of the family, had stopped when he realised who he was speaking to. She looked up with a tear-streaked face and eyes of pure, clean glass, and he stepped back from the balcony. “Carry on then.”

She smiled, wiped her tears away as if she had been entirely unaffected by the mandolin’s bite and continued onwards, louder than she had been before but careful.

In the evenings, after dinner, the five members gathered in one large but cosy living room, finding themselves on emerald sofas lined across the four corners away from the door. They erupted into loud discussion. Sometimes, they’d find themselves outside, watching the sunset from the west balcony. Others, they’d play a broken symphony to cheer themselves up, to make them laugh.

Today, however, an unnatural question had been raised by the youngest of the group: “When is baba coming home?” and thus, the pondering began.

Their house had grown from ashes of sacrifice, of defeated pirates and looted ships, of gold, and the eternally fragile consequence of hard work. They all knew what it took to maintain both the money they had and the sacrifice, and they knew that it depended on their father’s fickle health. He had not been home in five months, but they knew it was all for them. Everything their father did was to maintain the glory of his family, and they thought there was nothing else so honourable.

Their mother entered, and they gathered around her, finding a limb and clinging as she doted on each of them separately. “Fawzia, if you would like to become better at the mandolin, you must practice relentlessly… Riad, is that a bruise I see?” They listened to every word and reacted accordingly, laughing when she made a joke, even at their own expense. They sat for what seemed like hours until they began to push and shove at one another whenever their sticky limbs touched accidentally.

Today was different; today, she stayed for longer than usual, easing each child into a hazy daze despite their apparent disagreements. Each glanced at one other individually, finding themselves in the beauty of their loving words.

The door creaked open, unbeknown to the children. Their mother smiled, continuing to talk despite it, placing a loving hand on the youngest’s cheek and her eldest’s arm. Someone crept in just as their mother glanced back at the man, alerting them all to his presence.

There was silence as they all slowly turned to gaze at him, unmoving. Outside, the trees were swaying, the old house echoed and creaked, and their father, a man of great height and a dignified presence that demanded respect, had come in from the overwhelming warmth.

The youngest, the quickest of the family, left for him first, jumping up to wrap her arms around his neck. The next was the oldest, who needed no jump to reach the man who took him in the same as her. Soon, he was covered in them, each child huddled around the man for all the warmth and comfort they could ever need. It was a while until they let go, and when they did, they almost all launched into rousing stories. “Fawzia,” he called suddenly, interrupting their speaking once he realised his youngest had resorted to laying back in their noise, making space for her to move forward and in front of him. “How about you play for me?”

They collectively held back a groan, and their mother glared them into silence. He opened his hand for her, reaching out and allowing her to lead him down to the courtyard where her mandolin awaited her. She placed her bandaged fingers against it, keeping her eyes on her father before beginning to play.

Though she was definitely not meant for an orchestra, it sounded fluid, like a relief. The sound graced the silence, smothering it until nothing was left beside their calming hum. The mandolin sang in the air, caressing every lovely thought and smiling picture and making the youngest beam at it.

“You’re improving,” the eldest whispered gently when she had finished and sat back, nudging her arm before welcoming her to an embrace.

For the rest of the evening, they ate, they drank, they spoke of stories of their hometown, and he told them about every single gory detail from his time away. He told them of Ottoman merchants, British ships and famous pirates, and gold mines he did business with to trade to the highest bidder. He had met with kings, Presidents and supposed heroes. He answered every single one of their questions with a confident air and infinite pride.

Despite the world before his eyes, despite the royalty he had been in the presence of, he told them of how he found them at every turn and of his desire to be home, with them, in that very room within the Kasbah.

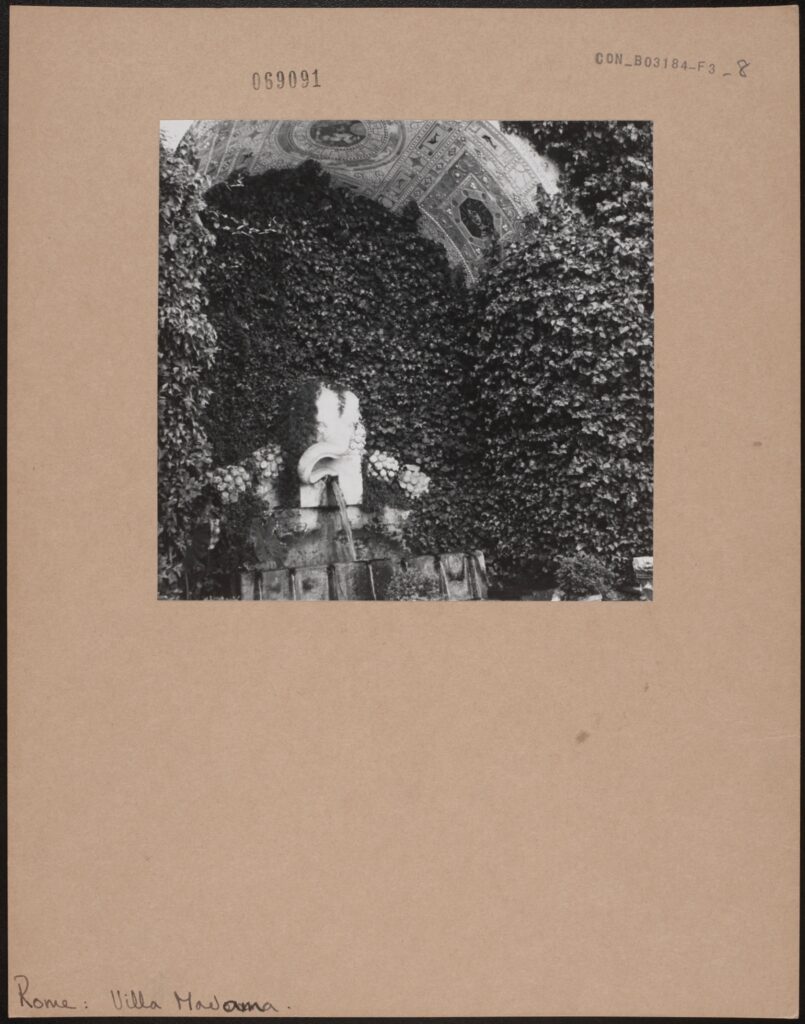

A hundred years later, people returned to the Kasbah, trying to find some semblance of identity within the ashes of what was left. They walked through the citadel, soft steps between piles of cleaned-up rubble, into what could be described as the only standing house at the top of the hill. Between the walls, echoing and creaking at every movement, they could hear the scraping and screeching of a young child with glass eyes sitting against a plain metal chair, trying to practice the mandolin. They found it louder in the middle of the house, near the new fountain and underneath the lavish chandelier. Gold had been stripped from the walls, but they knew the legend of the house: that a man had lived here with a large loving family and returned from his travels more than usual just to hear that scratch and screeching of that mandolin.

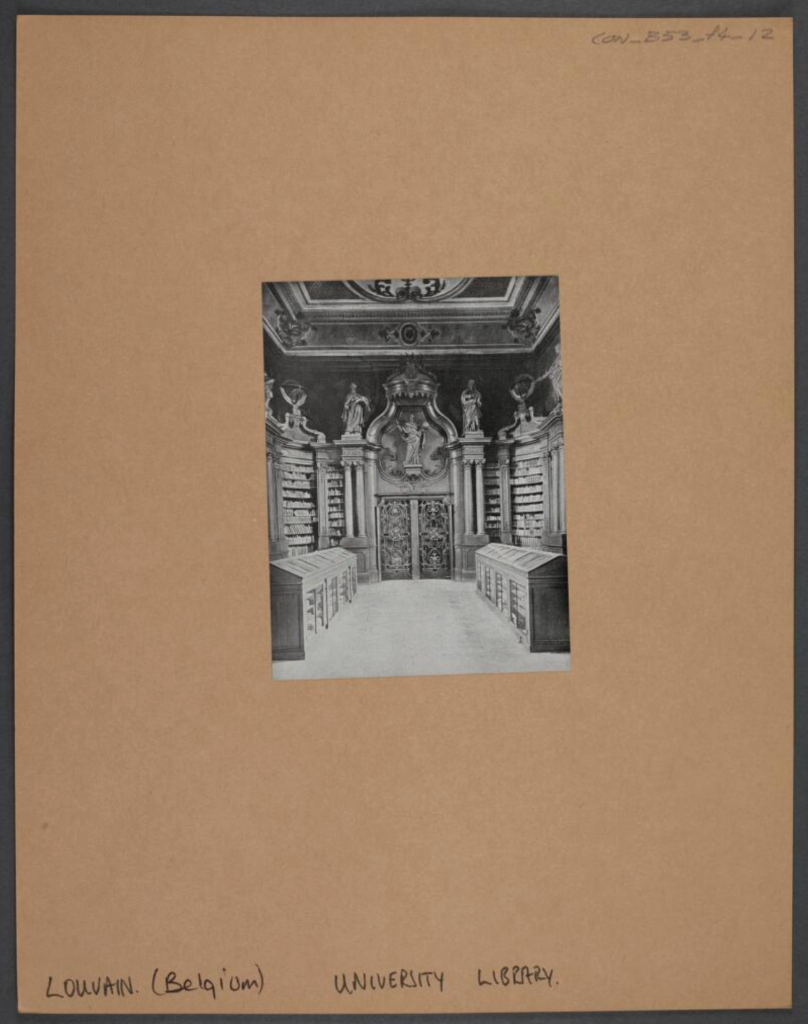

A black and white photograph mounted on card depicting the upper level of a house and balcony overlooking a courtyard (not visible). A large, grand chandelier is visible to the right of the image, and a white stone bust of a woman is shown to the left. There are rows of white stone arches lining the balcony, with intricate twisted columns underneath. The lower floor is decorated with patterned tiles. [CON_B00004_F005_016, The Courtyard of the Governor’s House at Algiers, Algeria.]

*

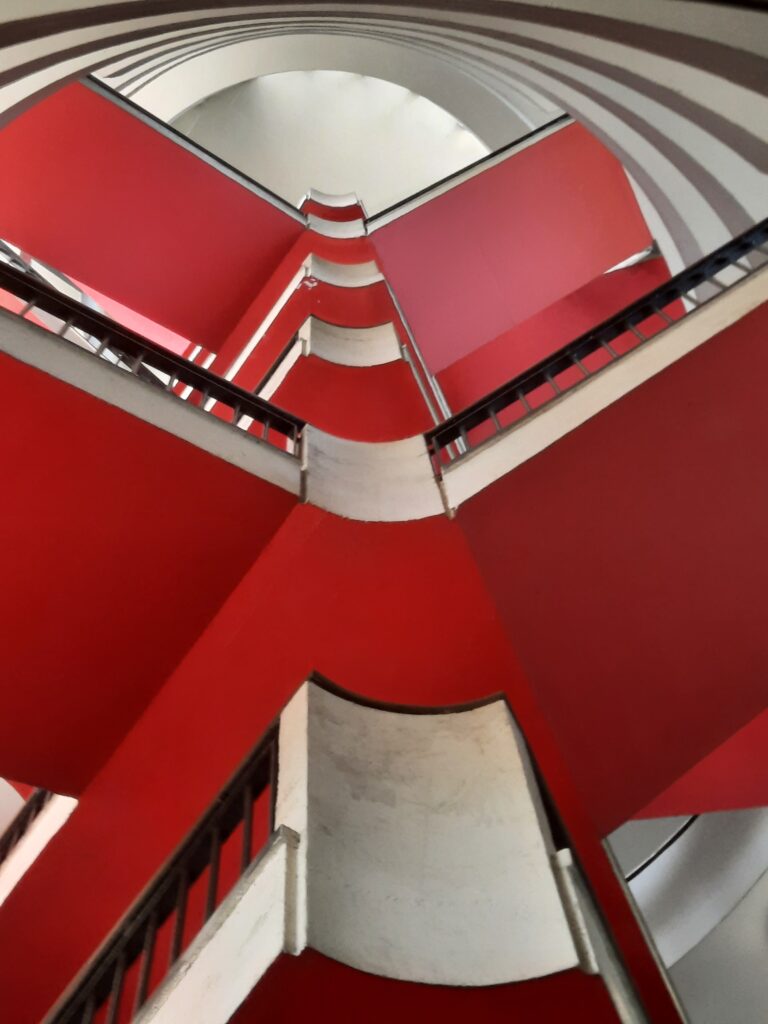

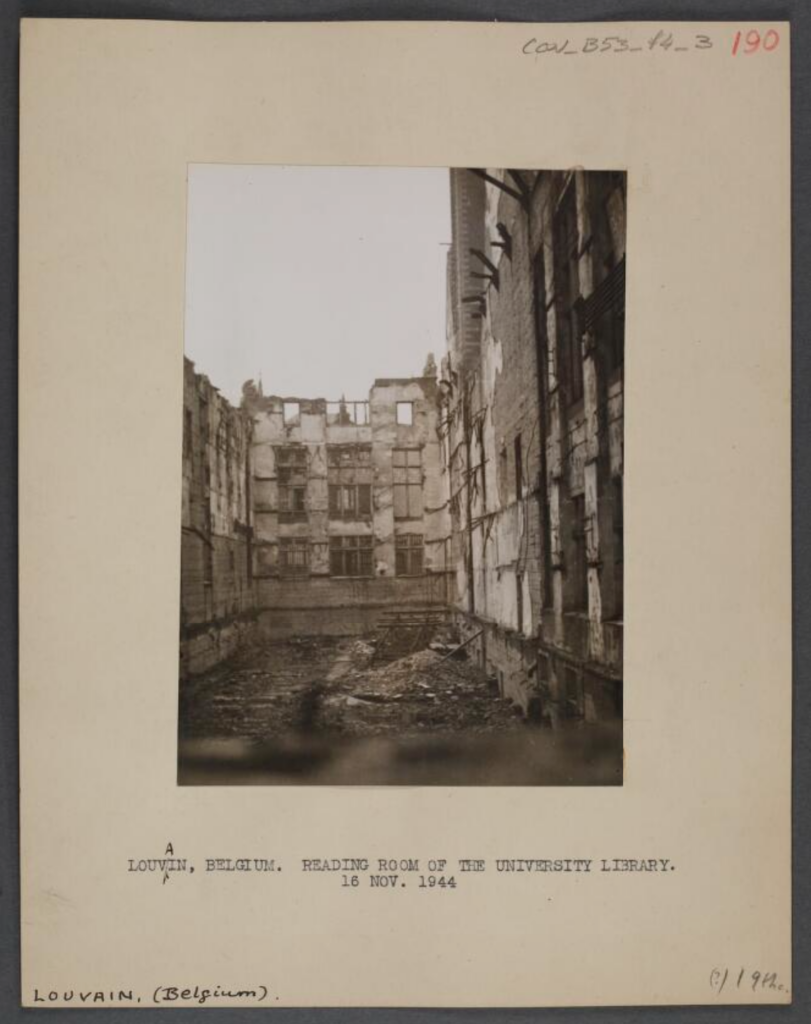

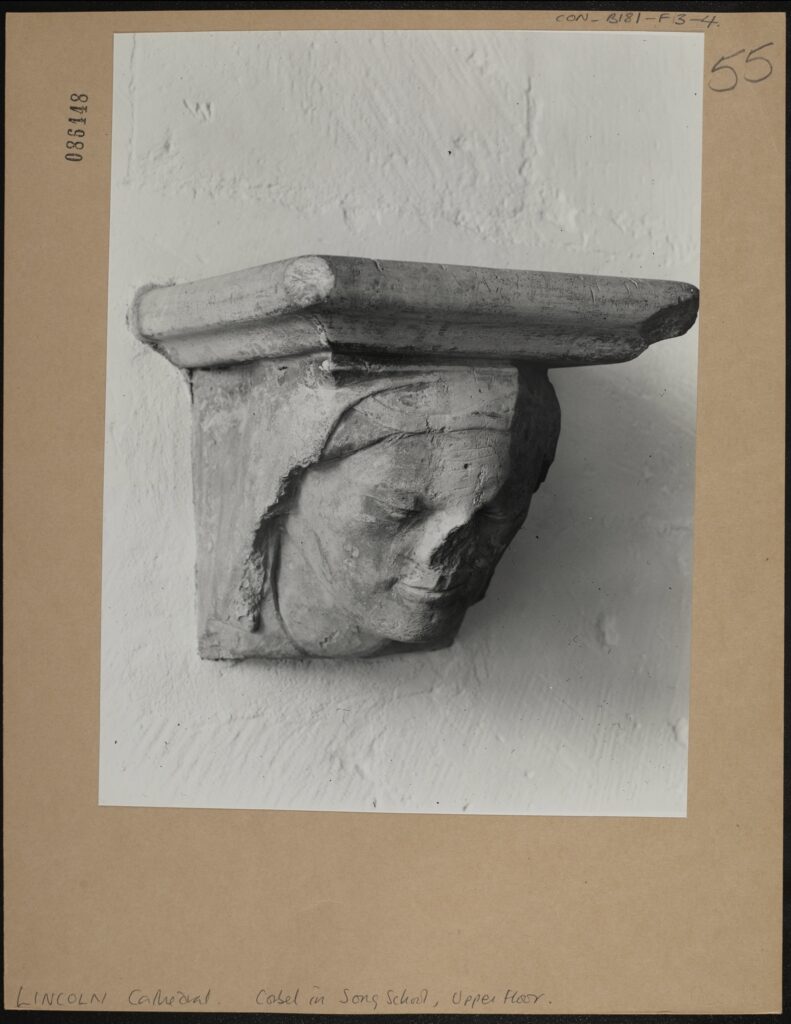

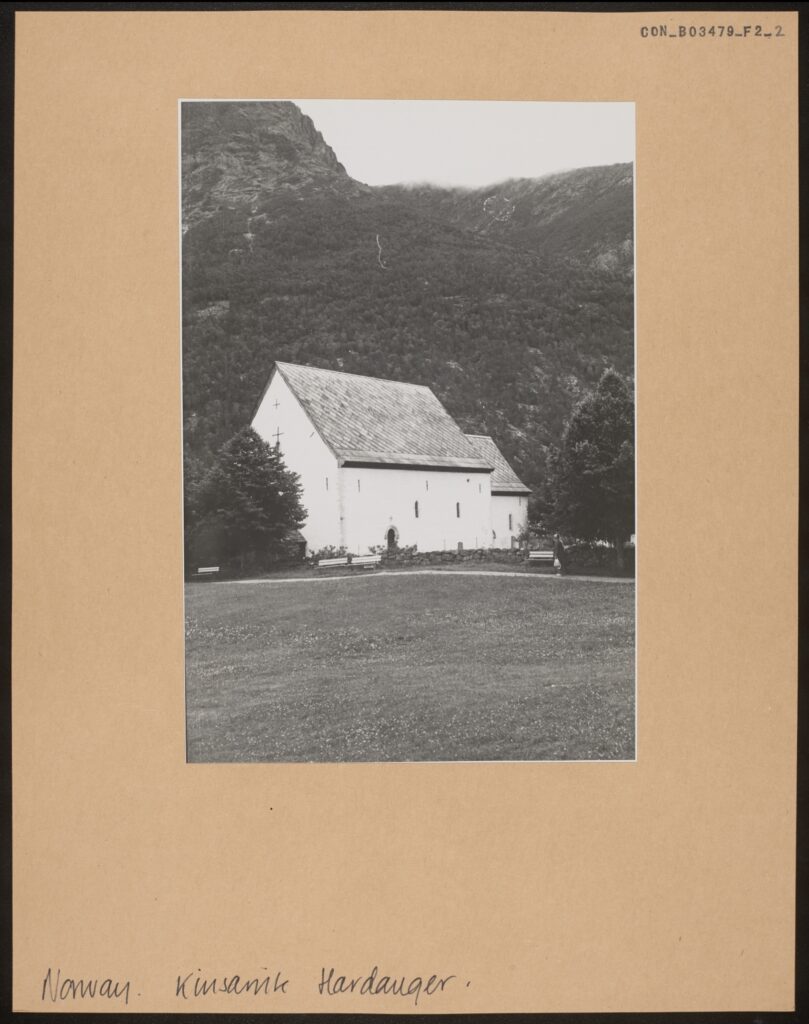

Story Four – a new day had come.

Birds leapt as a young man dove through, running against the speed of the wind that demanded to hold him back. Once again, his work was calling for him, and he chose to deny it until the very last moment. They had fought tooth and nail for the opportunity, contacted every sad man with an unexpected past who could like him enough to open doors for him; he hadn’t enjoyed it as much as he was expected to. He acted his way through every bit of his interview, keeping on the part until he was choking on the pressure to like it, and everybody he knew liked it beside him. The romanticised idea of a library, to sort and to catalogue, seemed beautiful on paper. Still, in reality, it made anything else feel like a holiday.

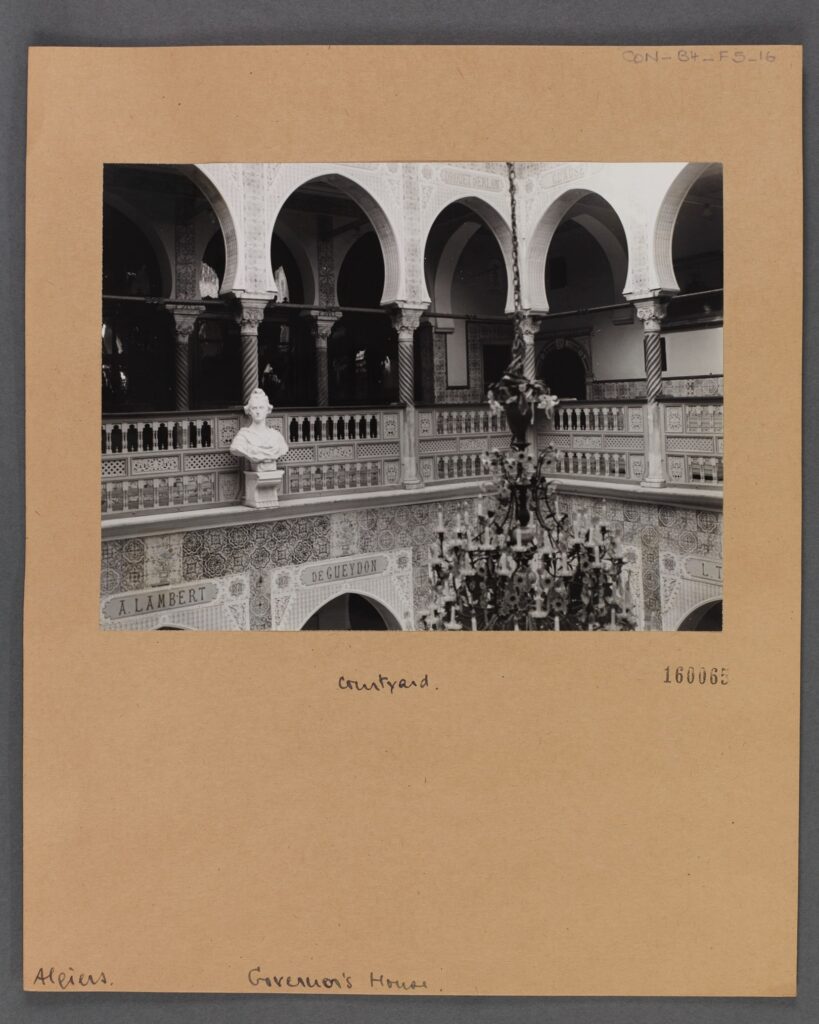

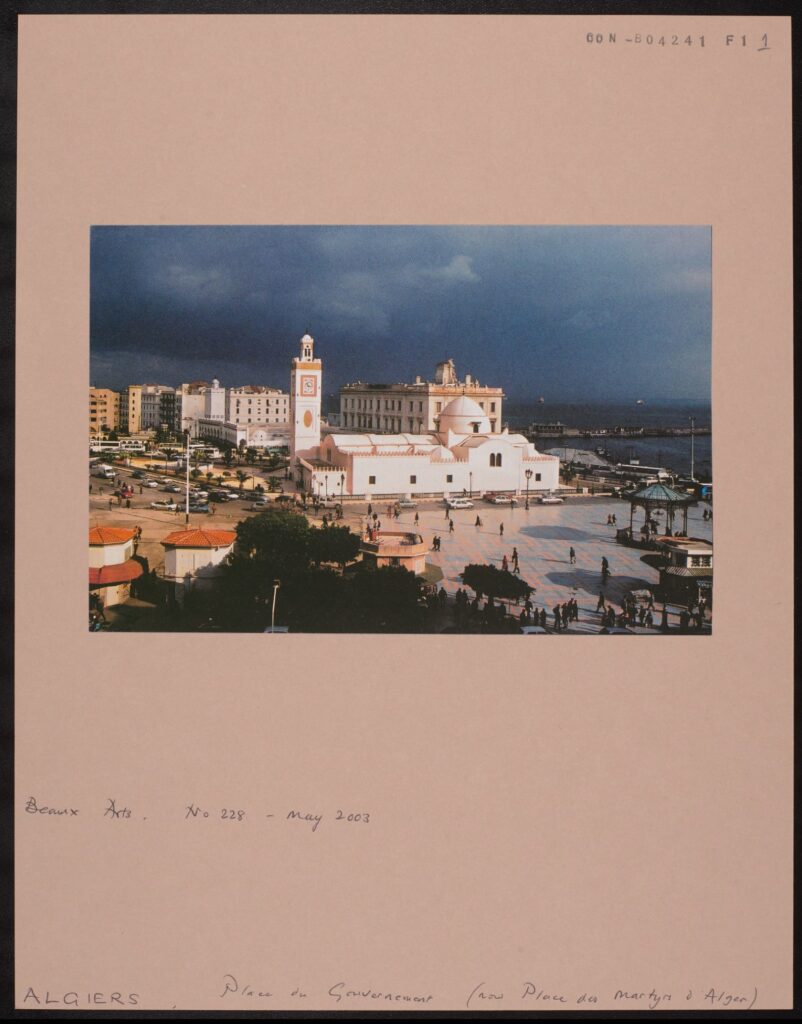

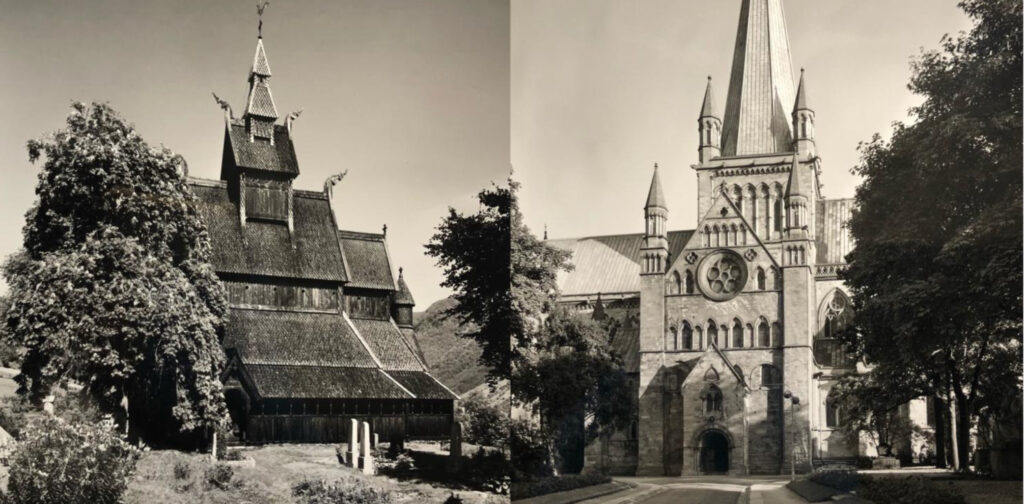

He raced through Martyr’s Square against time in the stifling September sun, stirring every speck of the peace the morning twilight brought. He stopped for a moment to glance up at the sky, to catch the image of a single bird so he could see how it flew – he wanted to look at every speck of everything. God knows how much he wanted to know, but time, it always ran against everything he believed in.

There was the sharp, piercing tune of his work-supplied telephone, a small, hard, handheld object that could only slip into the crevice in his bag that was supposed to hold his water bottle. He was convinced it would survive a nuclear explosion if it ever came to Algiers. He checked the name, four short letters appearing on the screen. His manager was calling. Oh NO.

He began sprinting again, racing through empty streets until he reached the avenue where his work was. As he turned a corner, he smoothed down both his dress shirt and trousers, passing by people who maybe would recognise either him or his manager one day, smiling and pretending to be calm until he hopped into a sizeable cathedral-like building, through the lobby and up every single step until he reached the one that would take him to his desk.

Though intrigued, he knew little about the building he called work. He knew it had been left over from French Occupation and that today it held government offices, including the records he worked with. Before that, the land held a mosque and an Ottoman trading station, but the specifics of each beguiled him. Who decided to build a masterpiece in such a boring part of town? Who had decided upon the arches of the doorway or the floor mosaic?

He thought about it all as he finally sat at his desk, wiping beaded sweat from his forehead onto a clean paper towel and throwing it directly in the bin beside his desk.

“Did you just come in?” someone asked, approaching him.

The young man immediately turned to where the voice was coming from, offended at the accusation even if there were hints of truth. A tall woman, roughly his age, if not a little younger, had found his desk and sat on a pile of papers he had carelessly thrown upon it. She was holding something in her hands that he didn’t care to look at, and he chose to rifle through his bag instead. “No, I didn’t just come in. I came in at eight, like everyone else—”

She held a hand up in defence, “Don’t play the blame game, I’m only the messenger.”

“Messen—” she slammed a large cardboard box in front of him, interrupting the question she had been about to ask. “Oh,” he whispered, “thank you.”

“These are from London, and they’re supposed to be very, very boring. Throw out what you want, keep what you want. It’s all supposed to go in the bin anyway.”

“We’re not usually that careless,” he responded, reaching down to his shoe to tie the laces he had forgotten. Late, messy, and disordered, he was really showing his true colours today. “Why?”

“This box has driven six different people insane apparently. I’ve looked through it, there’s nothing special so you should be fine.”

He allowed for an annoyed sigh, moving onto the second shoe before realising. “If you’ve already looked through it, why don’t you do it yourself?”

“Because I’m not stupid,” Her face brightened suddenly as her words twisted into thorns in his head, stabbing themselves deep into his back. “Good Luck!”

It took him all his will to hold back a groan, staring at the closed box as if it was his mortal enemy, someone he constantly lived in frustration with, a friend that was never meant to be. If he was to ever get started, now, when the heat hadn’t smothered them yet, was definitely the time.

The young man coughed as the box was opened, as a balloon of dust exploded into his face, shielding him from it for a few seconds. He glanced away, finding his elbow to cough into, and just as if it had never happened, found the box again with newfound eyes.

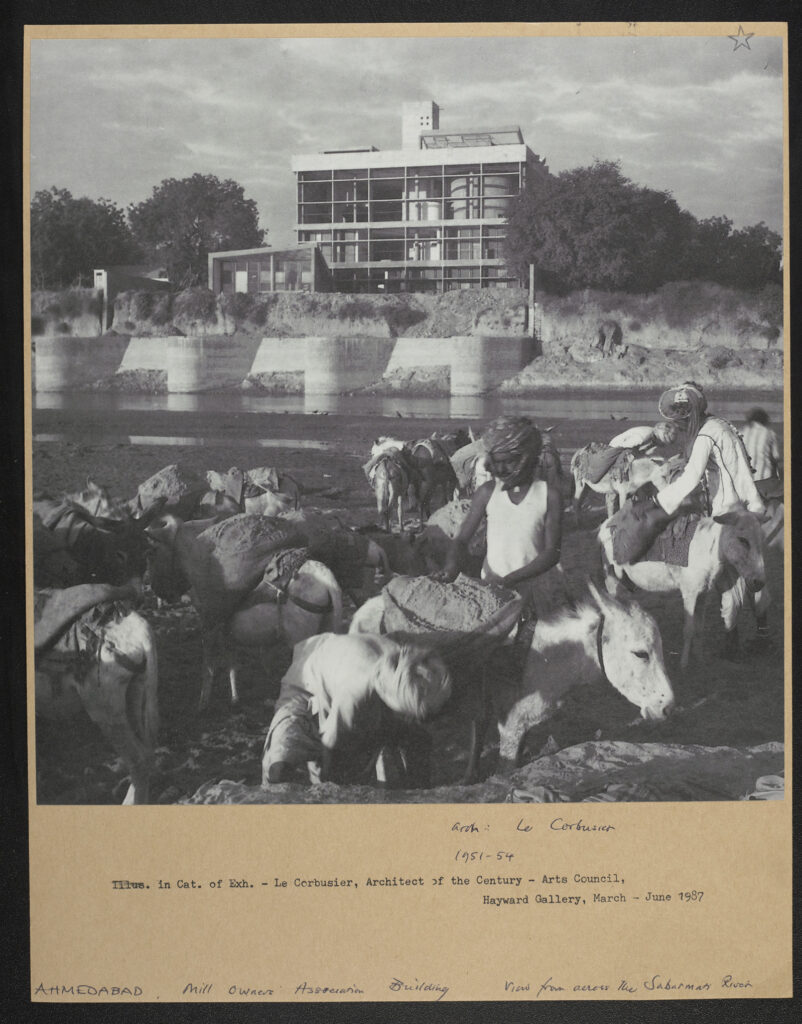

He pulled out the first photograph, and the second that he did, he found a figure moving across and back out of the frame again. He furrowed his eyebrows, taking in the image of a rock behind the man in the photograph and every single curve and edge. The young man glanced away and then looked back with narrowed eyes, only just missing the movement once again. He was almost sure he had seen the rock behind the man move, something added within the bulls and the boars.

The young man moved on to another, picking a random photo from within piles and piles he had strewn out over his desk and gazing at it as carefully as possible. It had been of a Roman Theatre, built in the city of Timgad before it had been hidden under the sands for a century. In the stands, there were people, and he found a small boy among his friends, cackling at the top of his lungs. He glanced away, looked back, and found pine-nut shells against the stone steps, the same his dad had bought and eaten for decades.

He called the young woman, and when he could, he took the short walk across the fray over to her desk, prepared to be either insulted so deeply he would think about it for days or deemed a genius above all else, but more of the first.

“Can you see that?” he asked suddenly, showing her the photograph.

“What?”

“There is a boy, and he is laughing. Look.” She did indeed look and found nothing. The picture was clear; there were ruins of a Roman theatre in Timgad, nothing special. She looked at him, before at the photo and back at him again.

“Were you dropped on the head as a child?”

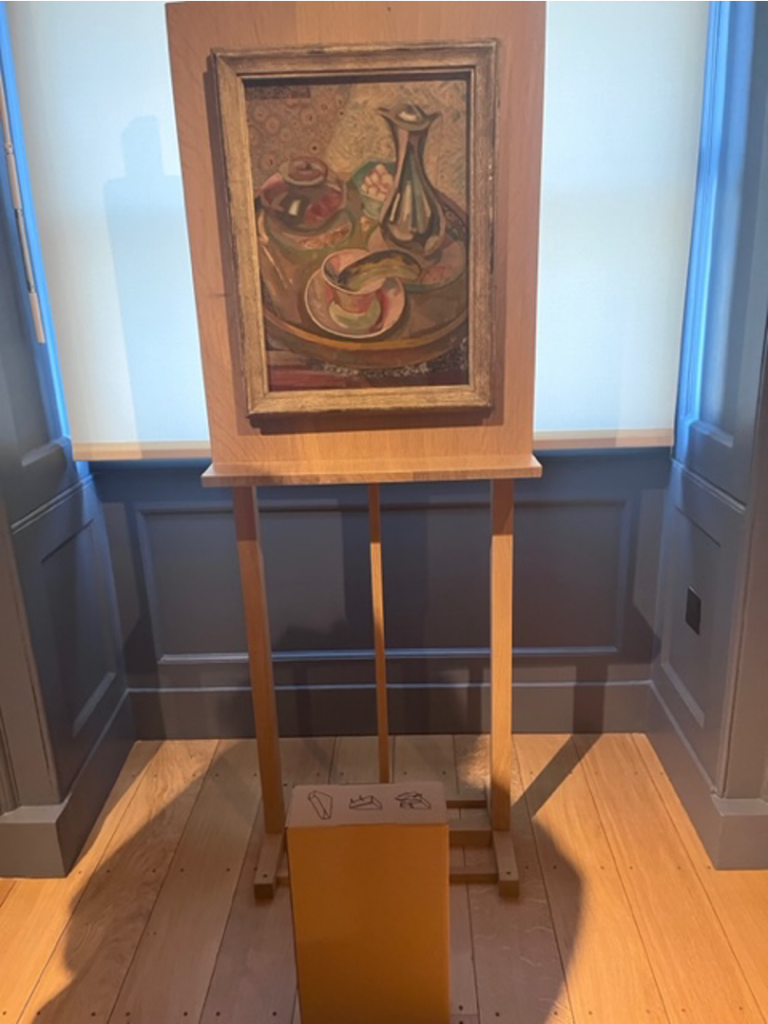

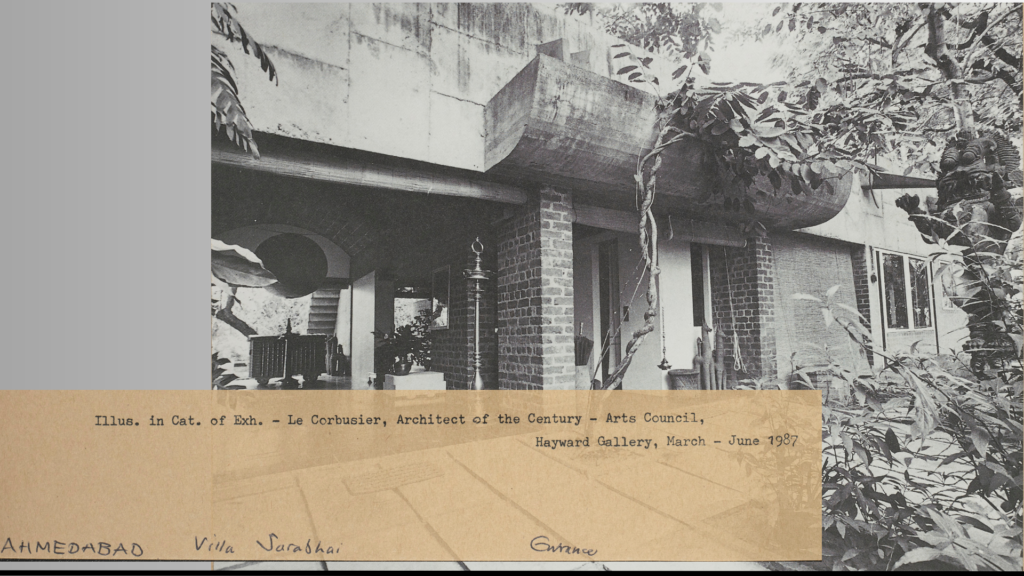

He groaned loudly, moving back the short distance to his desk and returning to the box. As he picked another photo, from the compete other end of the box than the first, he assessed it all. It was a palace he had been to once before, walking within the walls – it was now a museum, but with the same air as a house lived in. In the middle, he found a child sitting against a smooth metal chair in its courtyard, holding something on her lap. He squinted, trying to get a better look – was that… a guitar?

No, it couldn’t be. What she was holding was wider, had a shorter neck and presumably sounded different. He could imagine it sounding higher than a guitar, more fluid. He’d seen it once before, at a Raï concert he went to against his parent’s wishes. If only he could remember what it had been. A ma—man—

A mandolin.

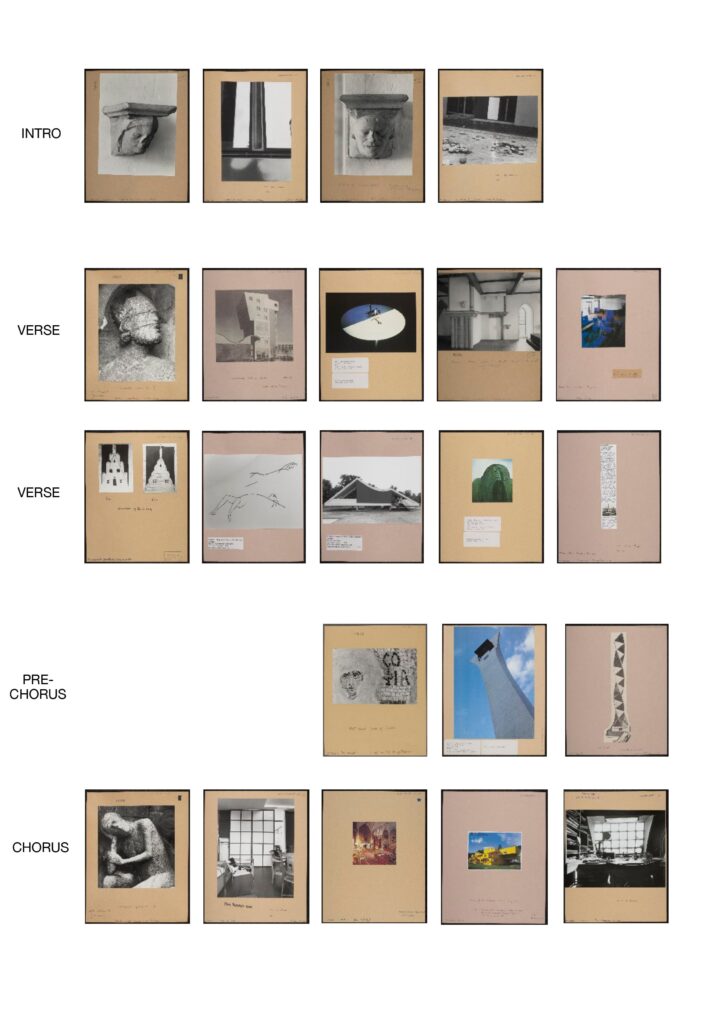

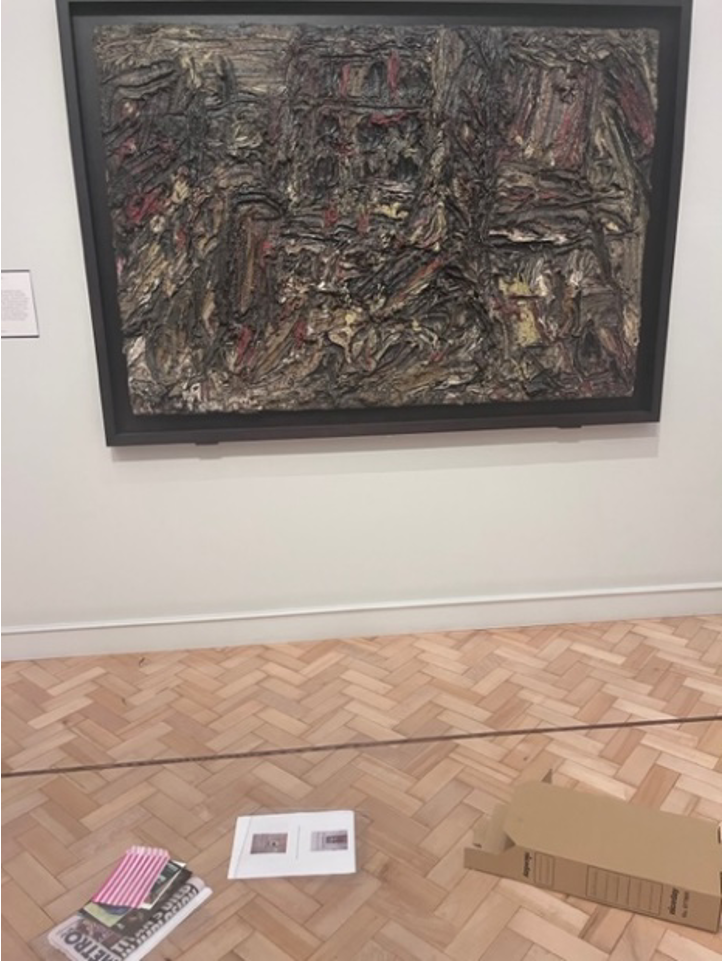

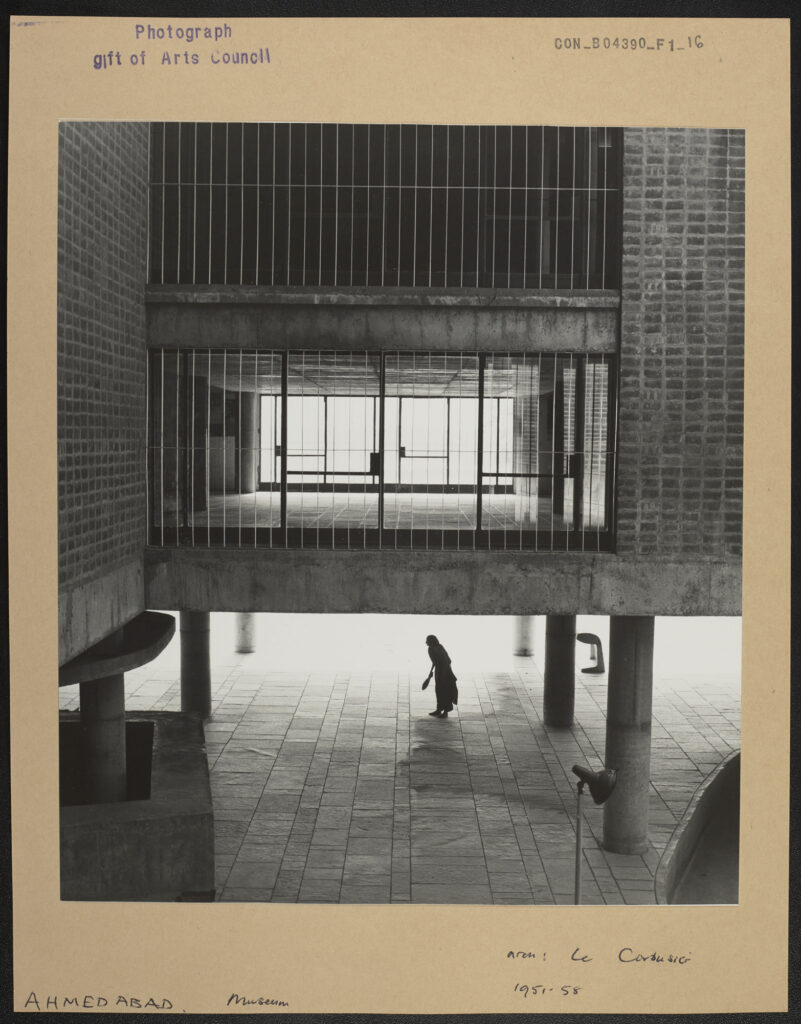

This was no coincidence, he realised after the first dozen. The young man furrowed his brow and continued, looking at each and everyone with the same process. He glanced once, turned away, and glanced back again to see the change, and in every single moment, he found happiness, love, and then joy. In many, he found the architect, the maker of the madness, a crafter. In others, he found people laughing, men amongst men, and revolutionaries before their time. He could see their faces before the blur of the camera, a symphony of all things good in the world, all things he didn’t have.

On his lunch break, he considered handing himself into a mental hospital and letting them run as many tests as possible to see what was wrong with him. Is that what the others that touched the box had done? It could not be expected – he was seeing things, people in pictures that didn’t exist. Only when he returned to his desk did he find them kinder, smiling softly instead of their usual mocking laughs, looking directly at him as if he was a kindred spirit.

He took the photographs home against his better judgment. If his colleagues wouldn’t believe him, maybe his family would. Perhaps they would give him the validation to make him feel normal and not completely insane for seeing an arm where nothing should be. The young man understood the moment he saw the house was empty, barren of all happiness, filled with only his misery: this path was his to walk alone.

Once he had finished the final photo in the box, out of hundreds, he sat back against his desk chair with his hands before his face. On the side, there was a filled plate of washed and peeled fruit, on the other was his phone. Only then did he realise the task that he had been given that morning – whether to keep or throw? They could not keep everything; they needed to make room to grow.

But it was magic. They were ghosts, waving back at him, telling him how to go on. It was more direct than he’d found in himself in years because they chose him. He couldn’t dare to throw away ghosts or discard magic like it was the skin of one of his fruits.

He picked up the first photo from the back of the stack, of the little girl and her mandolin. He looked away before looking back to her kind, glass eyes. No, he thought, this ghost deserves to be seen and found.

The next day, he woke from his bed as a man on a mission. He drifted through the square, holding the cardboard box as tightly as he could, ignoring the horrid ring that followed behind him. He was late, always late, but never for this.

When he reached his desk, he sealed the cardboard box, scribbling down the first address he could find for an Art Institution as far away and sent it down to the building’s postal office. He then approached the young lady, leaning against her empty, well-balanced desk.

“Can I borrow a pen and paper?” She slid one over to him without looking up. She only listened as he scribbled something against his thigh and folded it when he was finally done. It was only then that she looked up. “This is the last thing I’ll ask; can you please just give this to him?”

Her eyebrows furrowed, “Don’t let the box get to your head.”

“I’m letting go,” he confessed, “I honestly quit.”

She stood when he did, following after him to his desk. “I didn’t mean it, I don’t think you were dropped—”

Despite it, the young man laughed, placing the now-worthless papers right into the bin. “I think I might’ve been.”

The young man didn’t wait for any more answers from her, hooking his bag back over his back and walking out. He left behind only his telephone and a small note explaining where the box went. No one stopped him or even batted an eyelash at the action, at least not her. He had glanced back only once to see people drifting in and past it without a second glance at his existence.

But at least the photos will live on in a place that could be believed, in a place it could be loved and labelled, where they can have their own home with one another. It was all the young man cared about anymore, maybe the only other thing he believed in.

A new day had risen; he could do nothing else but walk away.

A colour photograph mounted on card of Martyr’s Square, Algiers, Algeria. The square is large, open, and paved with light coloured stone slabs. Pictured is a gazebo, a large, white mosque, and other ornate buildings. There are many people visible in the square, and a number of vehicles parked towards the mid-left of the photograph. The sea is a dark blue and is visible to the right of the composition. [CON_B04241_F001_001, Beaux Arts, No. 228 – May 2003, Algiers, Algeria – Place du Governement (now Place du Martyrs a Alger)]

*

Louisa Hamereras

Courtauld Connects Digitisation

Queen Mary University of London

Internship Participant

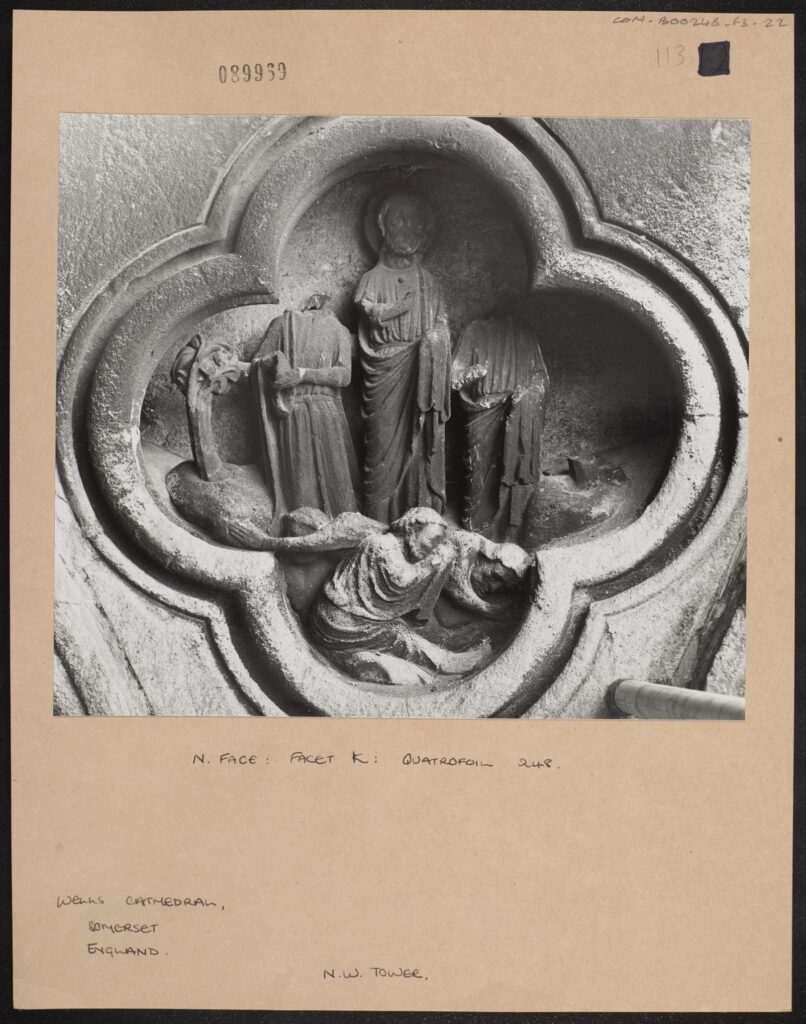

CON_B04390_F001_035

CON_B04390_F001_035 CON_B04390_F001_055

CON_B04390_F001_055