My name is Rosa Coomber, and I was lucky enough to work with the collection as the Digital Narratives and Storytelling Intern from August 2022 to the end of July 2023. I was excited to join this internship not only due to the opportunity to work with an incredible collection, but also due to the apparent commitment to creativity and freedom fostered by my colleagues. Digital narratives and storytelling are necessarily vague phrases; with a collection as vast as we have at the Conway, and a staff and volunteer body so broad and dedicated, there are more than enough stories to tell! After studying for a few years, I was keen to take a break from essay writing, and instead sought to ponder the question “how else can we tell the story of this collection?”

It turns out that there are almost infinite ways to do this, but the one that I spent most of my time on was Suzon’s Clues. My aim was to delve into the details of individual pieces in the collection and to document the physical experience of the library that we all know and love. A video game seemed to be the perfect medium for this, setting a mystery against the sights and sounds of the Conway.

[Image: Suzon’s Clues Title Screen. Background image: Tea Room, Conway Library, Courtauld Institute of Art, London, Jan. 2023. Photograph taken by the author. Sidebar graphics created using Procreate © for IOS]

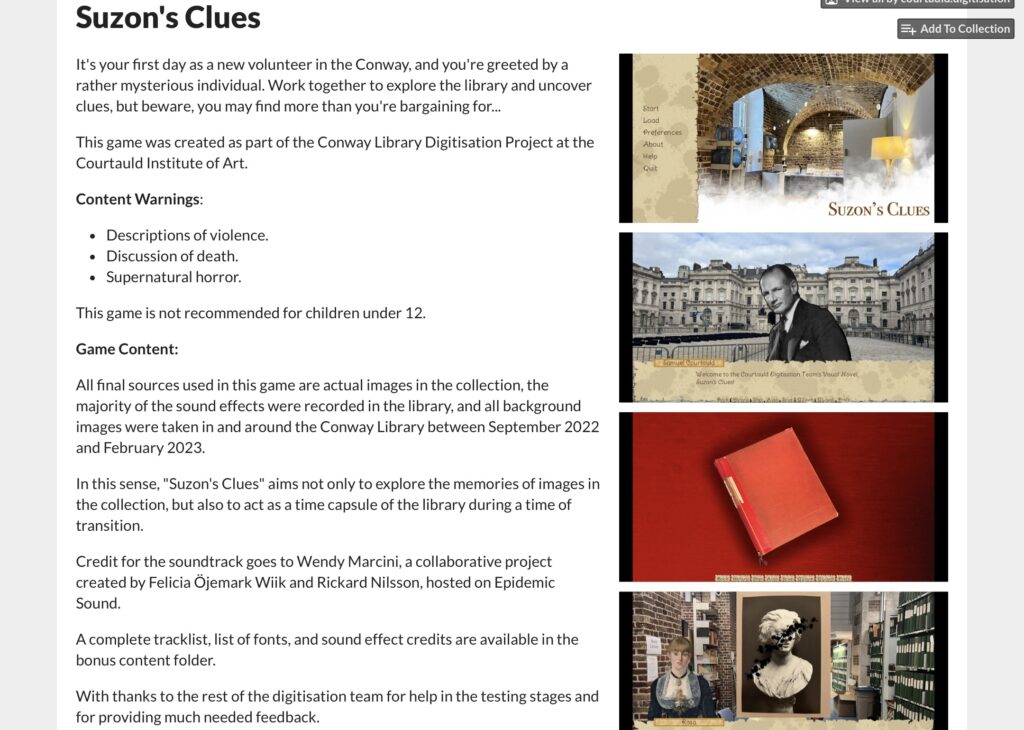

“It’s your first day as a new volunteer in the Conway, and you’re greeted by a rather mysterious individual. Work together to explore the library and uncover clues, but beware, you may find more than you’re bargaining for…”

Gameplay

It’s time for your first shift at the Conway Library. You arrive at the Courtauld Institute of Art, collect your volunteer pass, and make your way downstairs. You can feel a presence following you, but you push the thought to the back of your mind; you’re in Somerset House after all, a building with hundreds of years of history, and there are bound to be things hanging around. You open the door to the Witt Library, where you are suddenly intercepted by a mysterious young woman who introduces herself as Suzon. She seems to have been expecting you, and can barely contain her excitement. Suzon explains that she needs someone to help her decode objects that are materialising in the library; they appear to be Conway photographs, but each of them is obscured somehow. It’s going to be more complicated than simply finding their box numbers and filing them away.

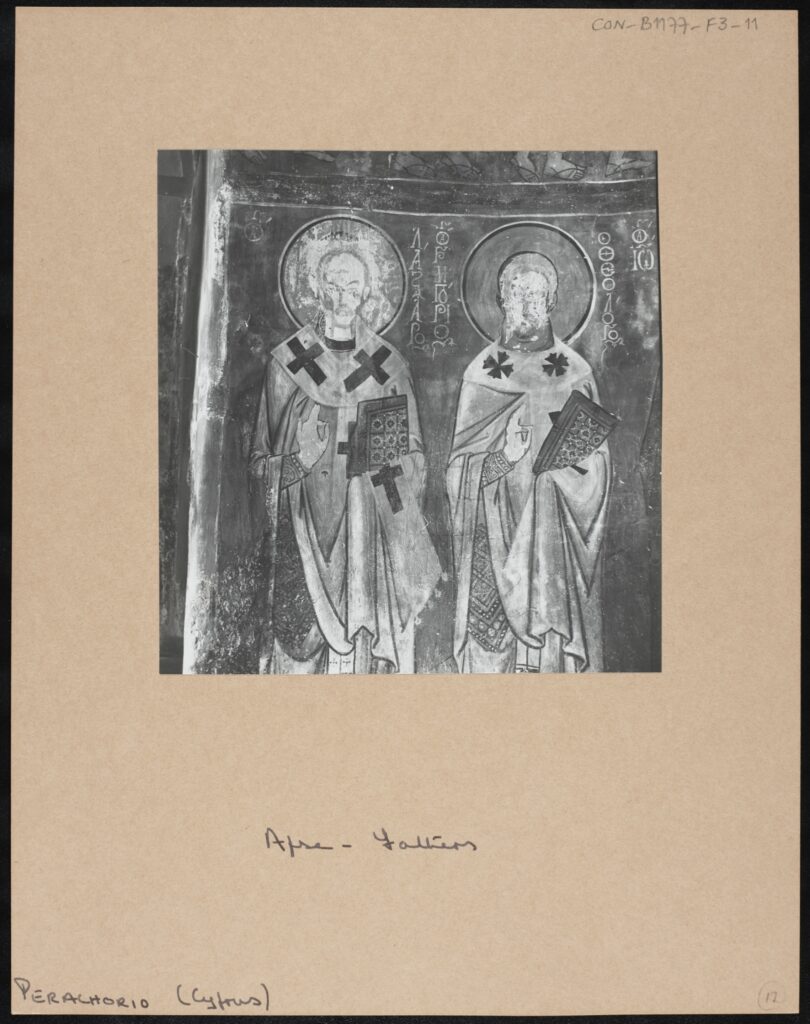

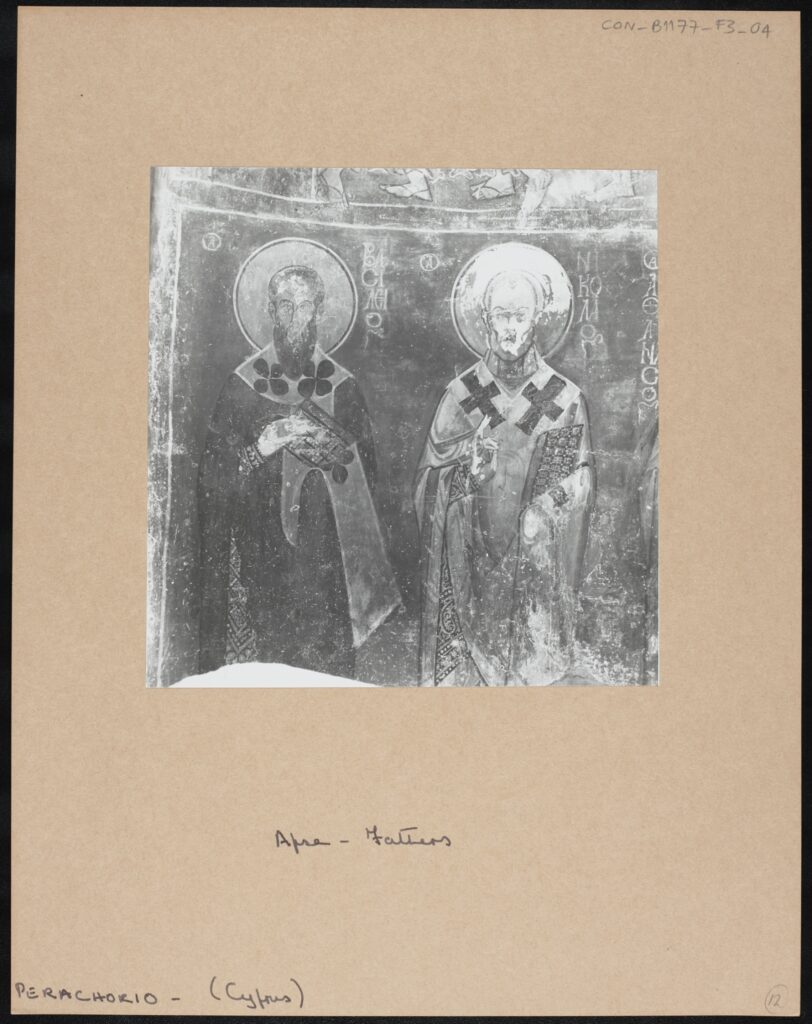

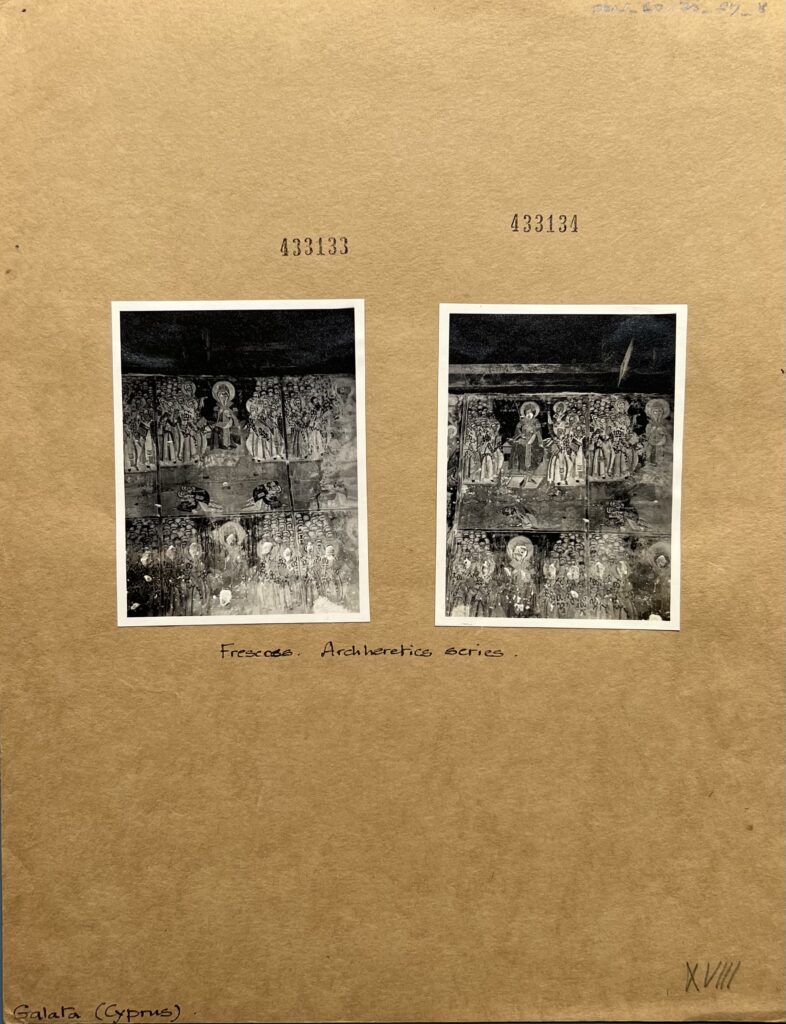

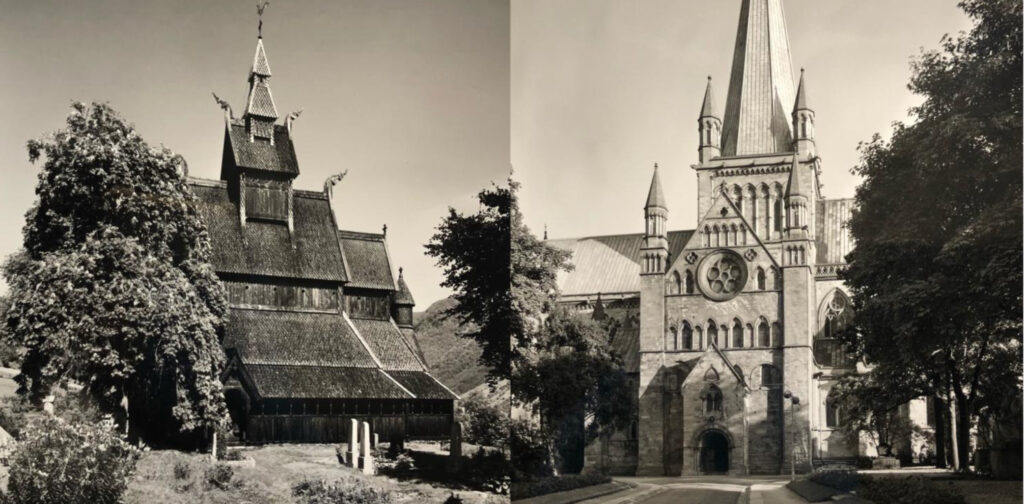

Through a series of multiple choice questions, the player explores the library to find clues, whether these are poems, newspaper clippings, or even witness testimony from yet more obscure characters. Once they are cleaned, translated, and stitched back together, they are returned to their rightful places in the library. The aim of the game is to learn more about the photographs in the collection and to integrate them into their historical and cultural context. The more clues the player finds, the clearer the picture becomes. This not only applies to the photographs, but also to the appearance of the elusive Suzon, who seems more familiar as the story progresses. There are four main chapters and one bonus problem, where the player has to opportunity to solve the mystery of Suzon herself. The game is intended not only as an educational exercise, but also as a kind of tribute to the library as a physical space and a centre of memory. This game is not recommended for children under 12, given occasional horror-related subject matter and descriptions of violence and death.

Inspirations

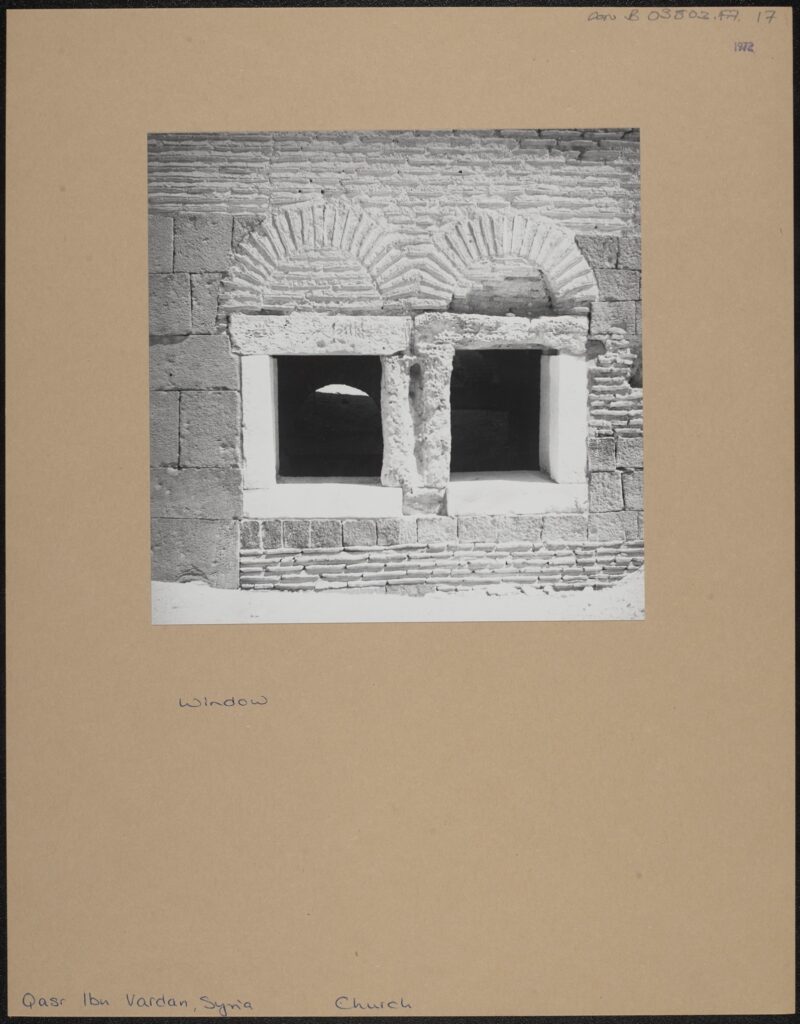

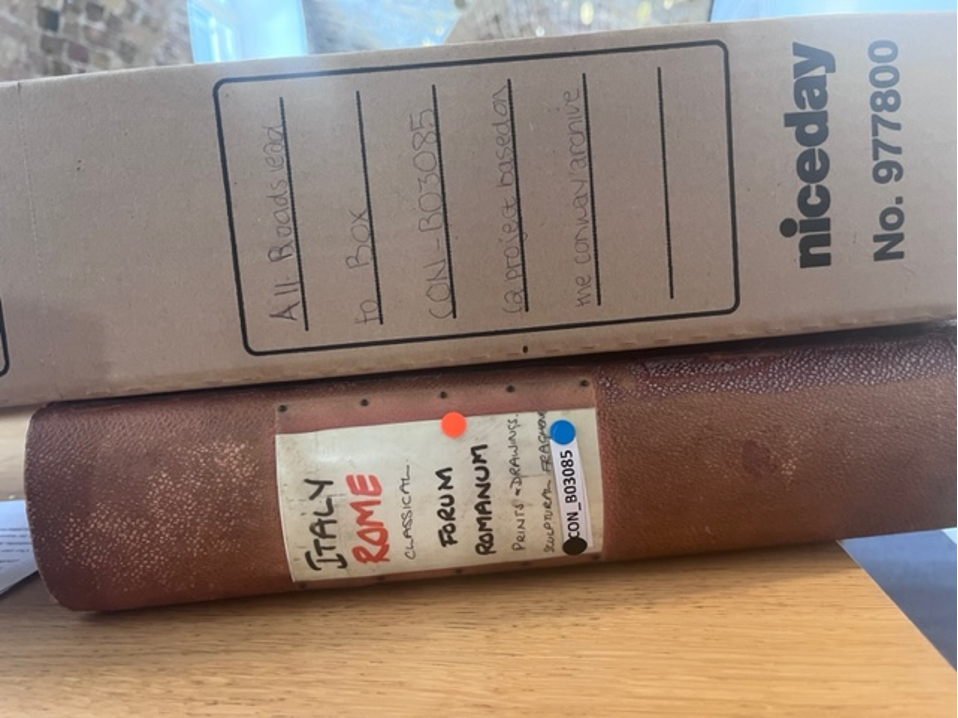

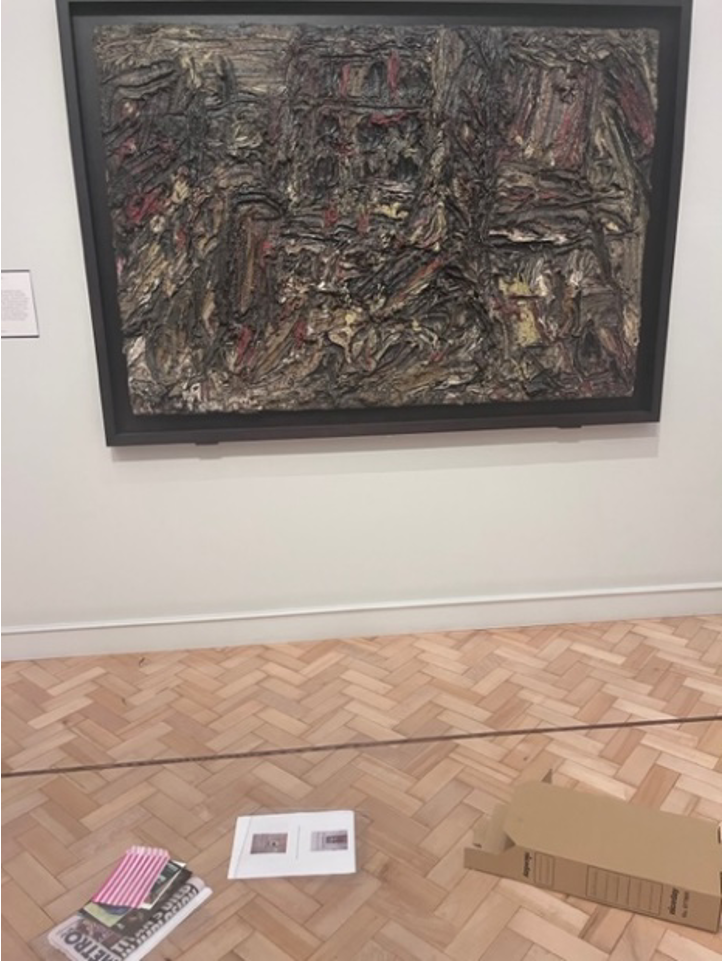

Before I settled on creating a video game, I was more focused on the “point of view” element of the project. I had come across an interesting photographic project from the Wellcome Collection’s volunteering department, which photographed the route from Euston Road, inside the main building, and eventually ending at the library itself. This project had practical purposes, of leading volunteers to their work space, but it also made me think about materiality, and what significance these seemingly innocuous and functional photographs would have in future years. Tom Bilson, Head of Digital Media at the Courtauld, had spoken to us often about the importance of documenting the collection and library “warts and all”: scuff marks on folders and torn labels on the red boxes. My initial plan was to create a kind of photographic project, documenting the volunteer experience from the volunteer’s point of view. Through compiling these images, I hoped that we might create a faithful visual representation of the Conway Library experience. It is interesting to note, between September 2022 and the time of writing in July 2023, the Wellcome Collection photographic route is nowhere to be found online, including via the Wayback Machine. This is perhaps testament to how fleeting these moments in time and space truly are, even with the seeming permanence of the internet.

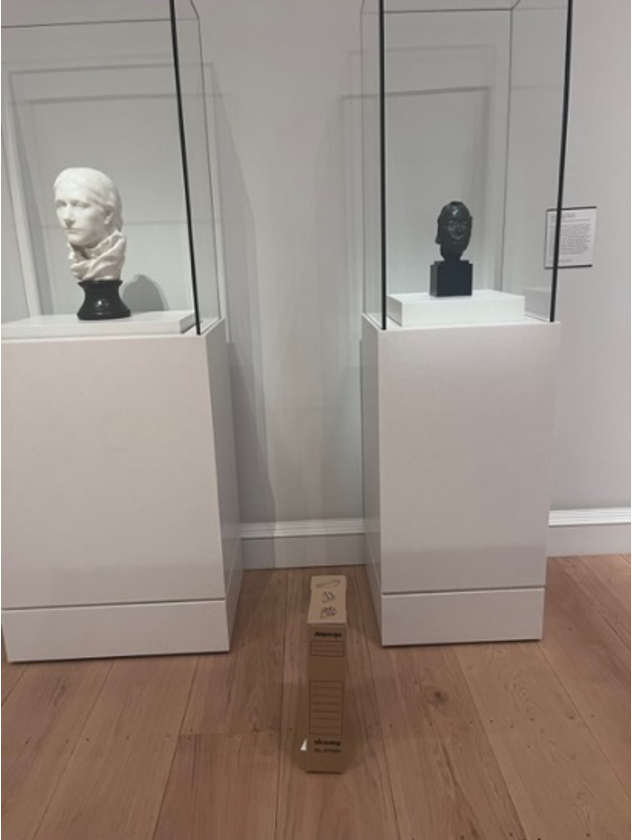

A selection of images taken in and around the Conway Library, Courtauld Institute of Art, London. Photographs taken by the author, Oct. 2022-Feb. 2023.

It was only once I started actually compiling these images that I realised what a resemblance they bore to a typical video game route. I have always been interested in more immersive, interactive learning, and so finally I settled on creating a POV supernatural horror/mystery game. The Conway Library, and its setting underneath Somerset House, is the kind of environment which is naturally ripe for spooky goings on; indeed, I have heard many stories of ghosts clattering about the vaults or floating across the courtyard in the middle of the night. Given the importance of featuring the space in almost every scene in the game, it made sense to import some of its ghostly energy. I am a big fan of horror games, and horror in general, but I have seen very few educational games with a horror slant (most of these would be better known as horror games with an educational slant, see Baldi’s Basics, for example). The mystery genre plays into this as well, as my aim was not simply to unsettle or scare, but also to explore and investigate lesser known pieces in the collection through the lens of the supernatural.

Research

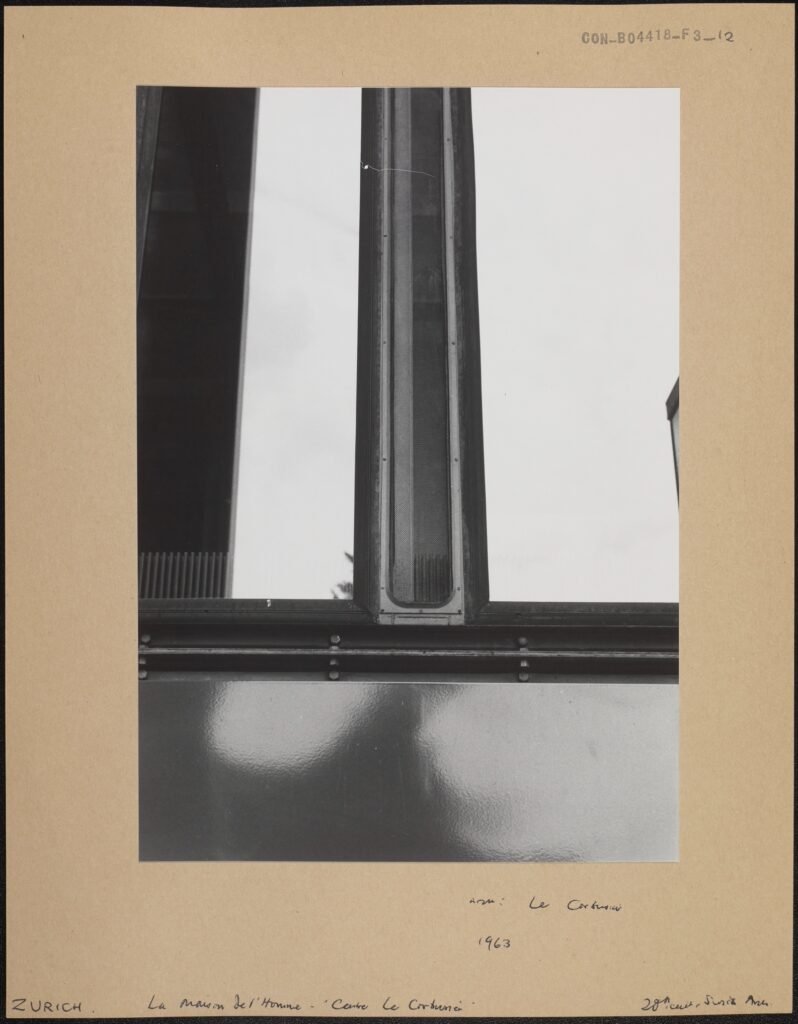

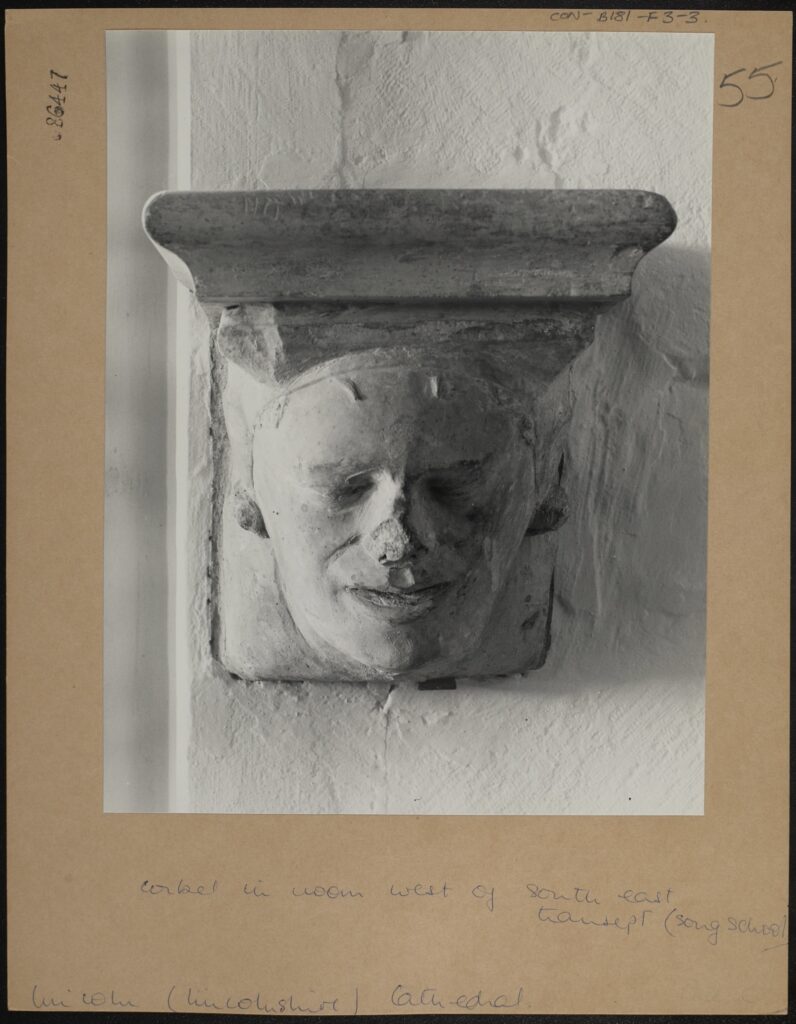

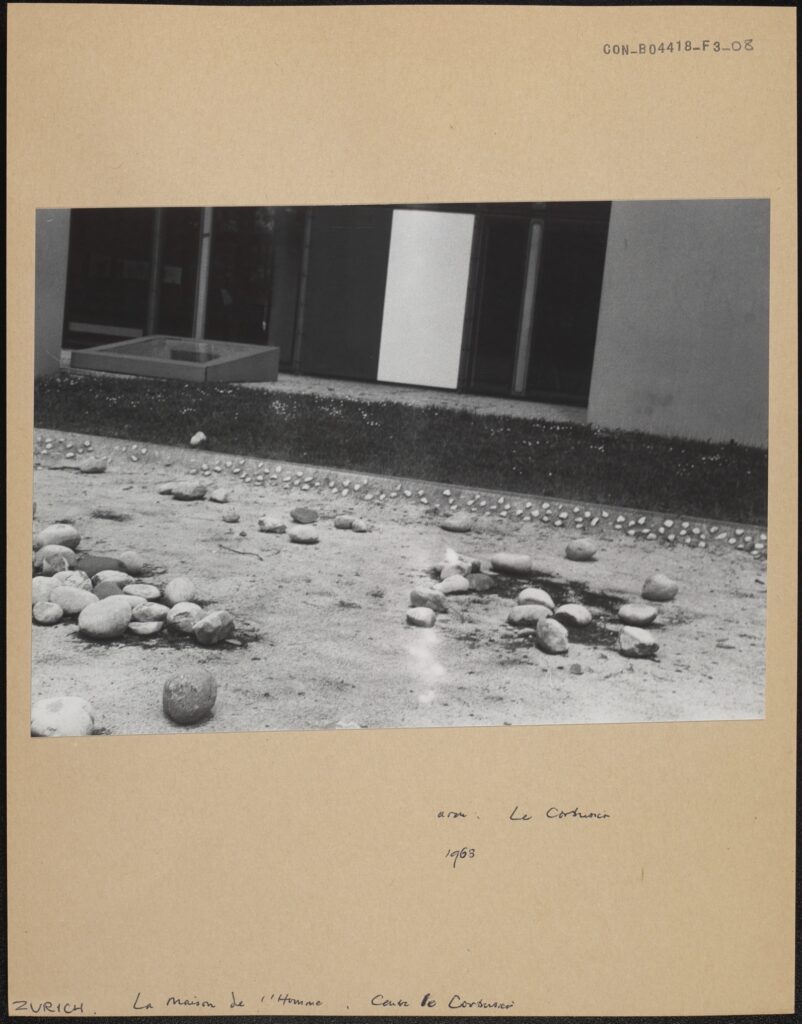

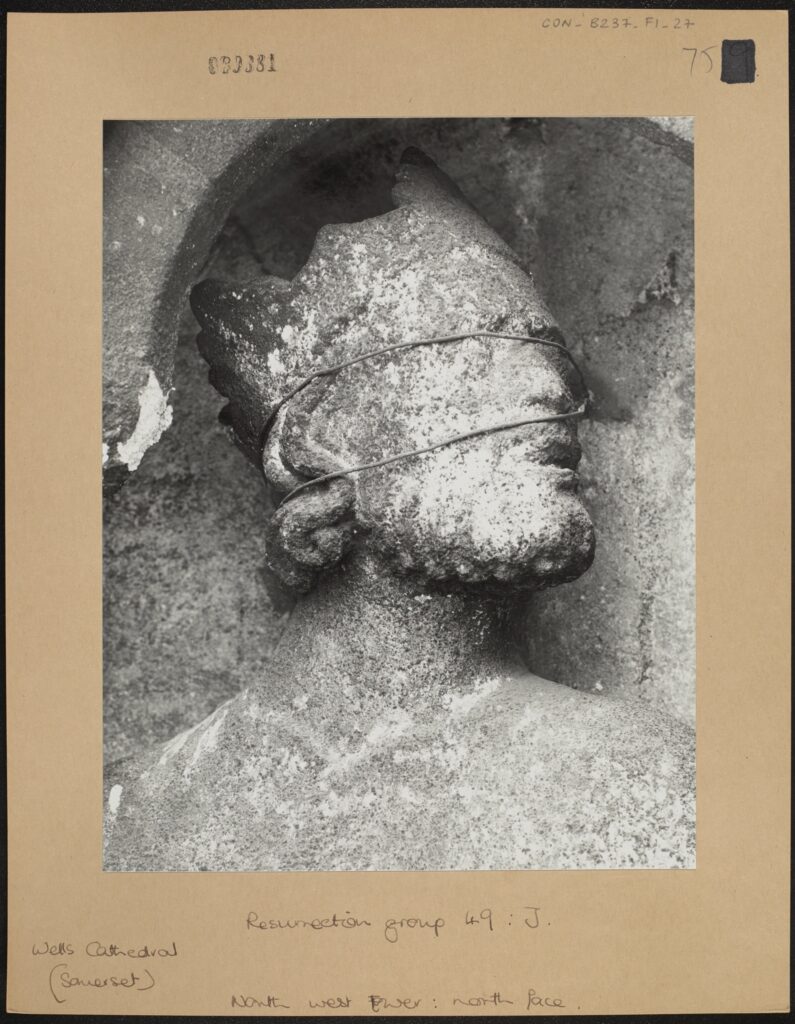

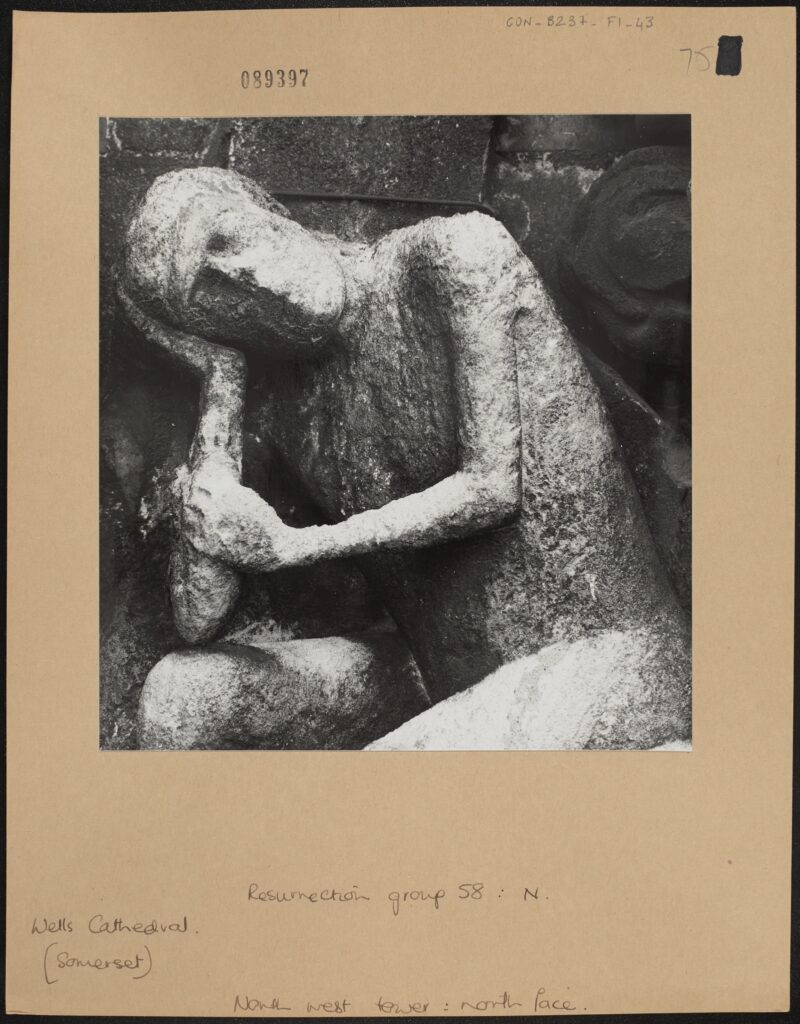

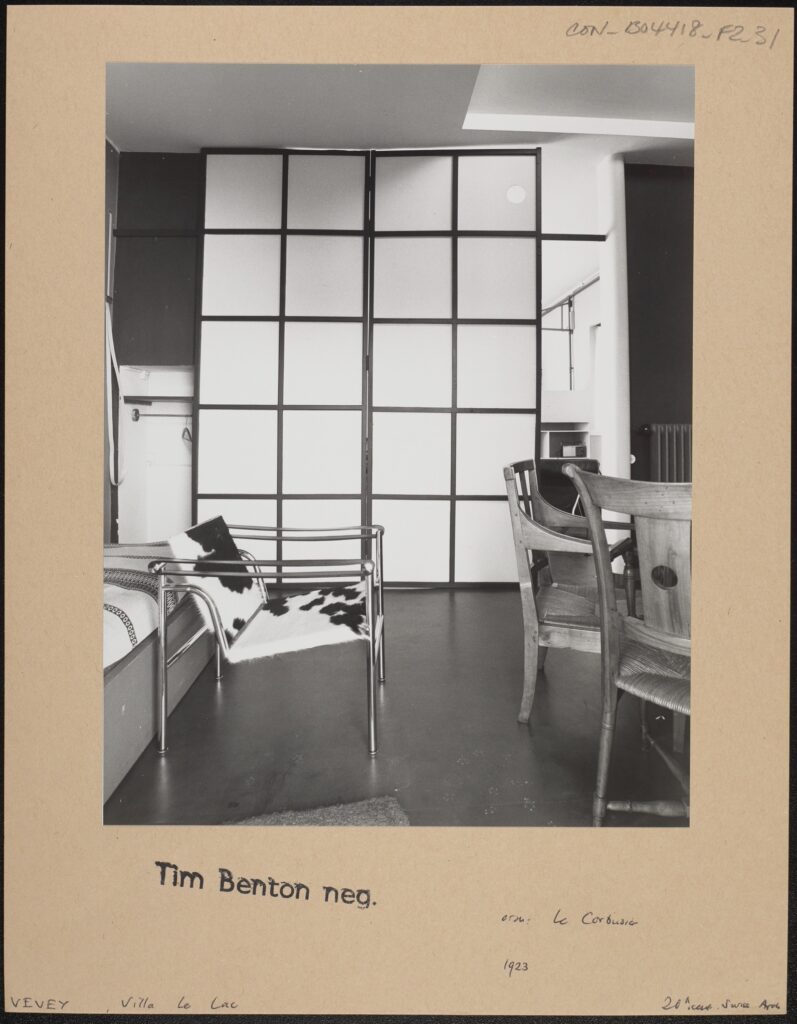

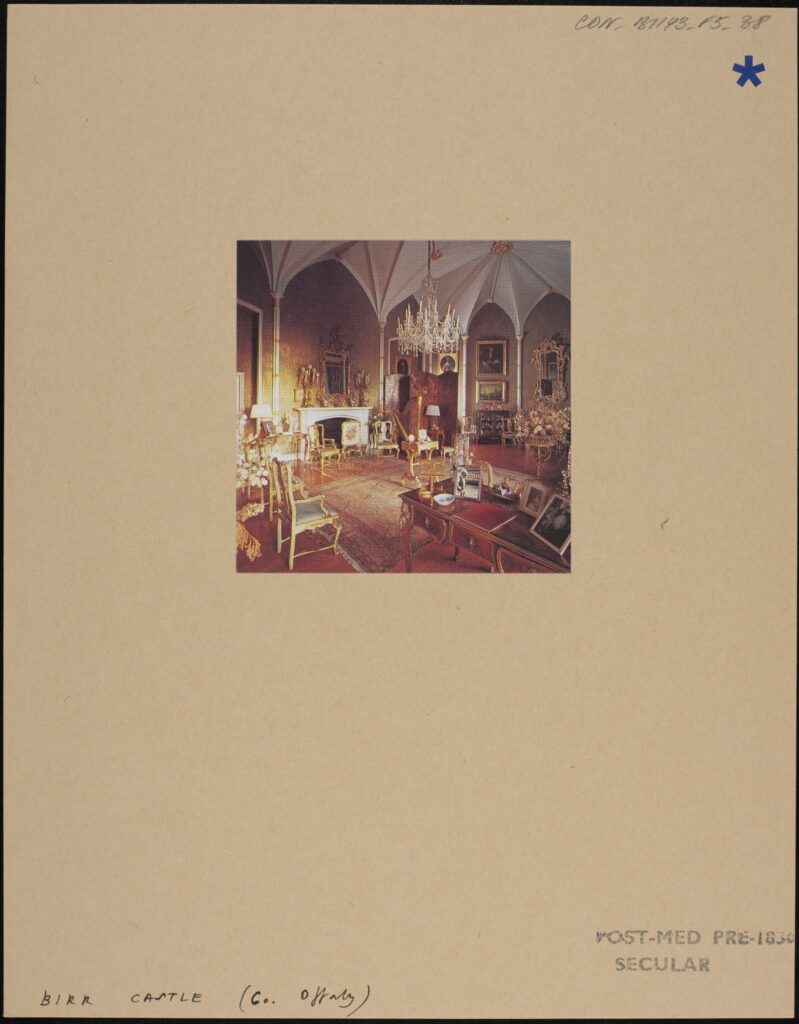

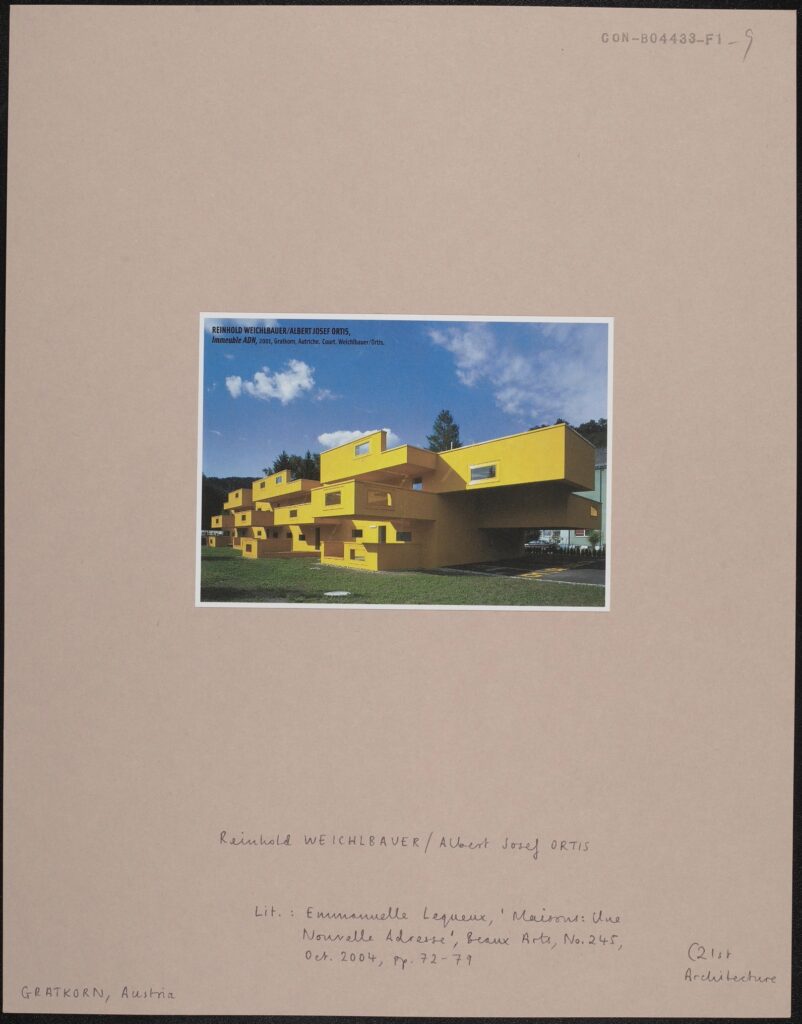

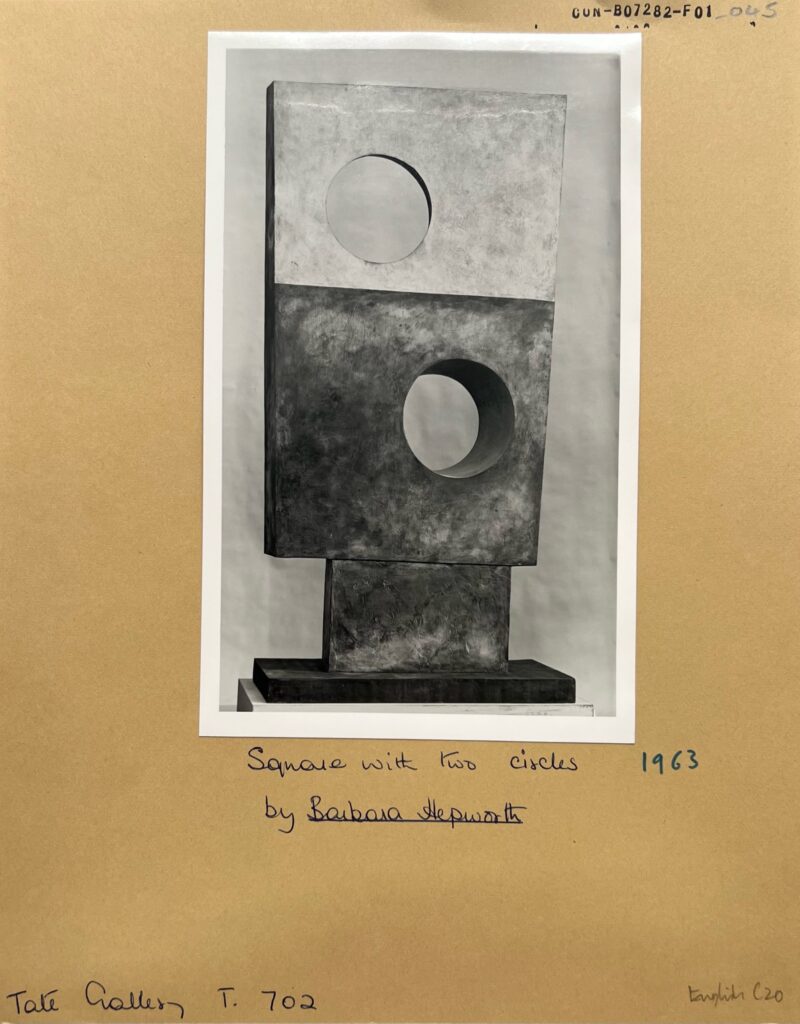

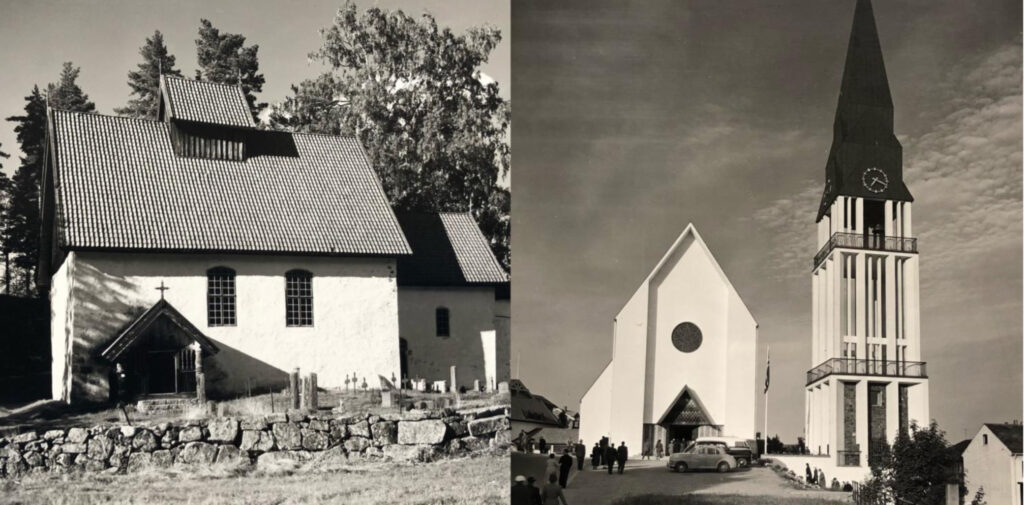

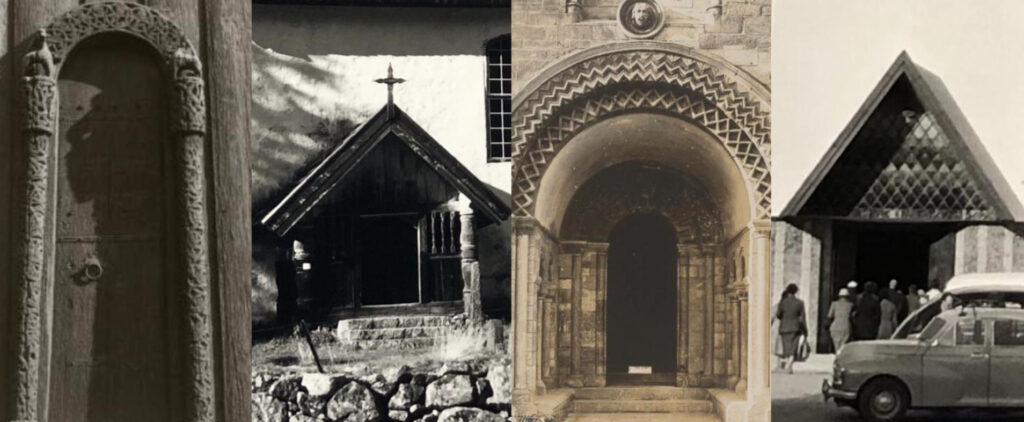

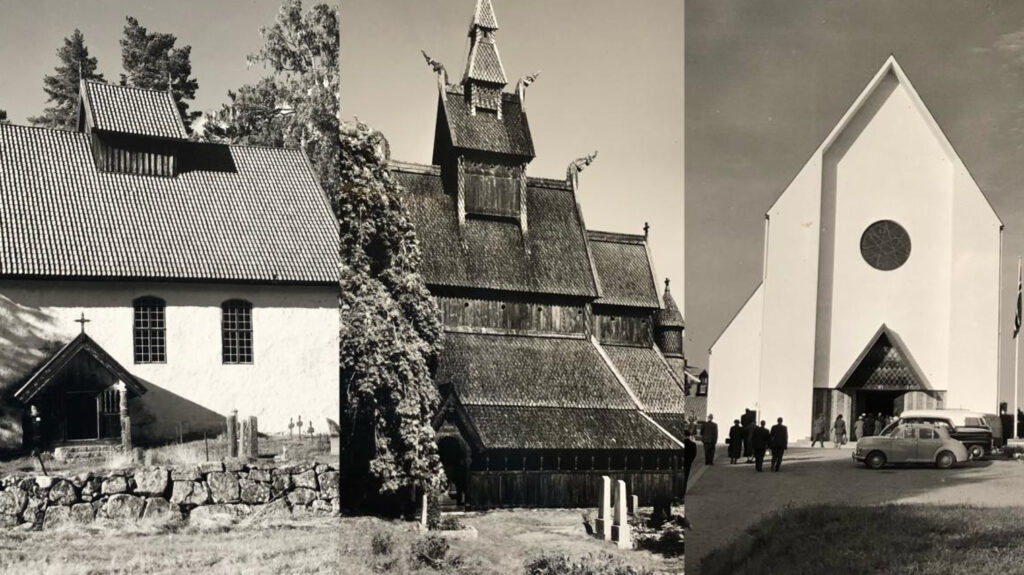

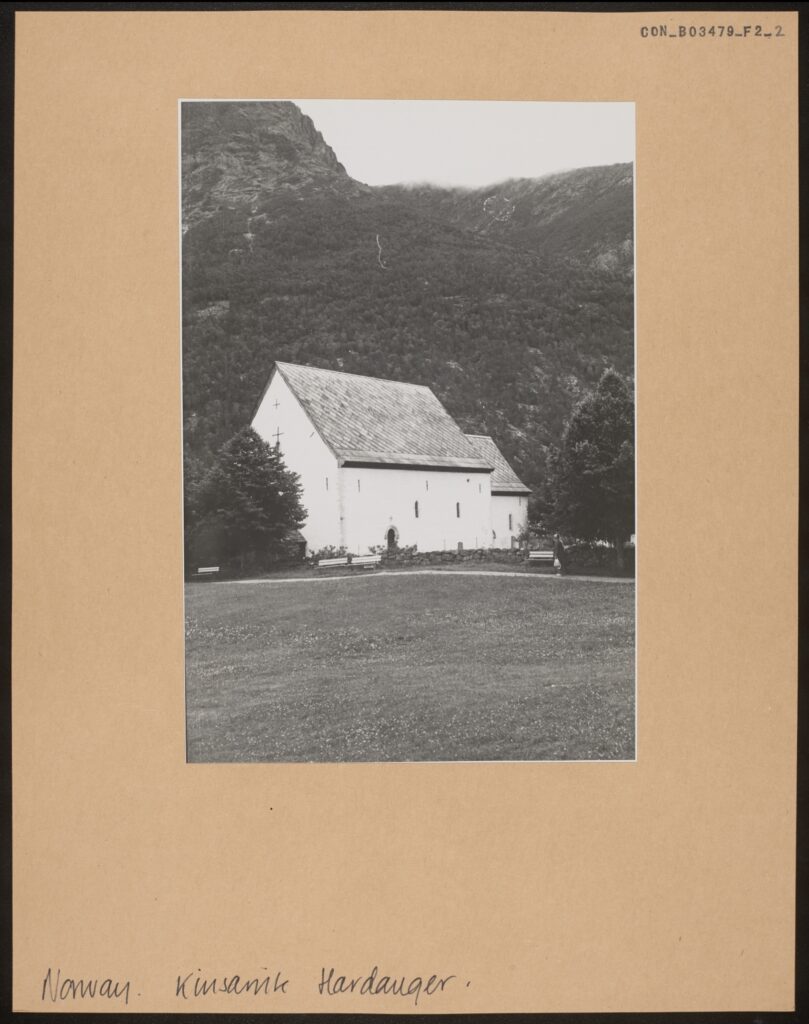

After settling on this genre, I began to explore the collection, choosing boxes almost at random, and trying to avoid anything I’d spent too much time on before. After a couple of days of this, I settled on ten sources, which I quickly realised I would have to whittle down to four, an experience I feel is not uncommon when exploring the collection. The sources are as follows:

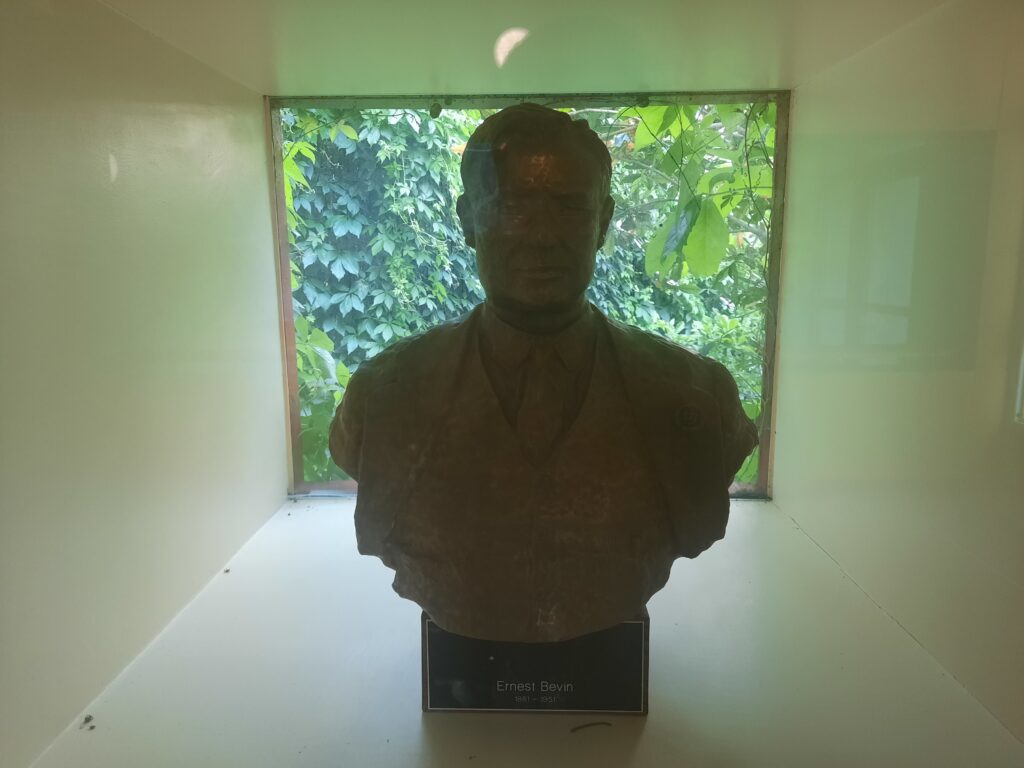

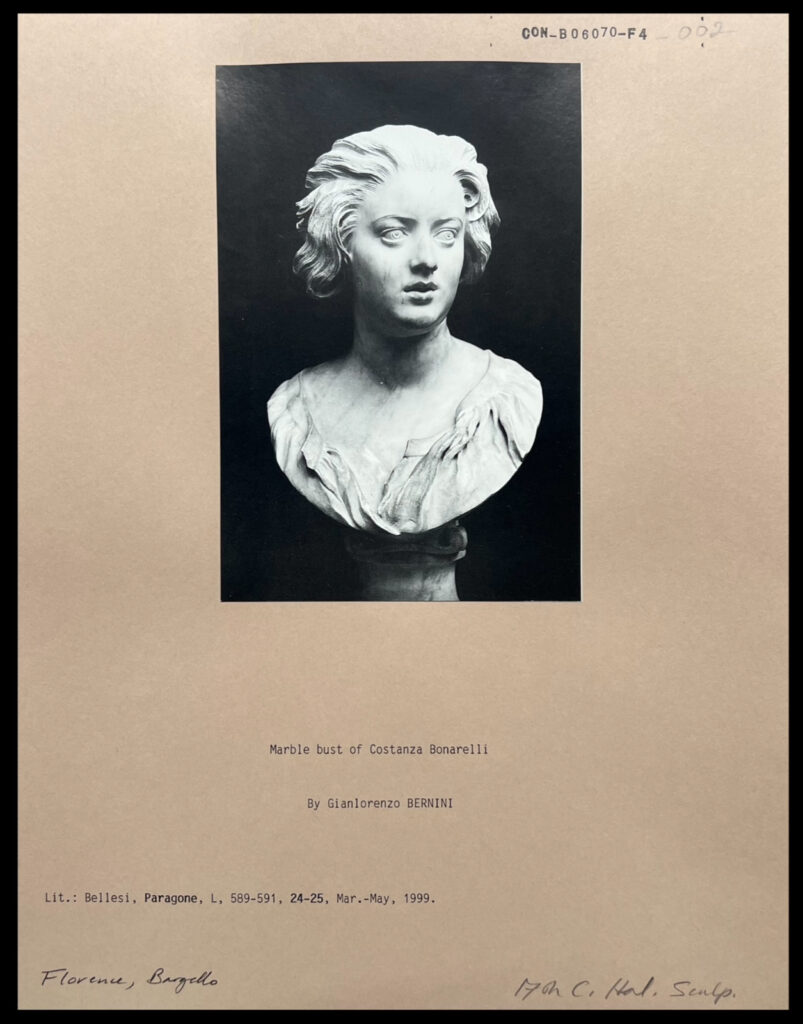

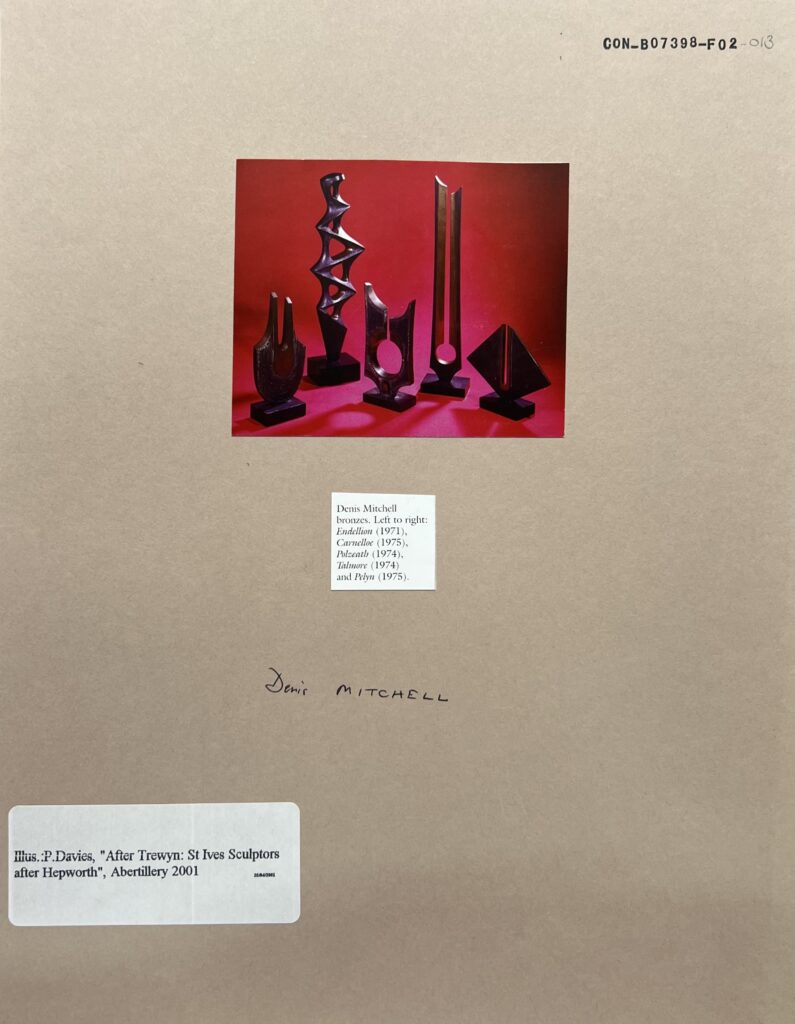

[CON_B06070_F004_002] – Marble Bust of Costanza Bonarelli by Gianlorenzo BERNINI, Lit.: Bellesi, Paragone, L, 589-591, 24-25, Mar.-May, 1999. ITALY: Florence, Bargello.

This source was the first I chose, and another piece that cemented the decision to focus on pieces in the collection with darker histories. On the surface of things, this is a simple bust of a woman named Costanza Bonarelli, sculpted by famed Italian sculptor Gianlorenzo Bernini. Once I had researched the image further, I discovered that Bonarelli eventually had an affair with Bernini’s brother, and in response Bernini hired someone to slash her face with a dagger. Immediately, this sculpted image of intimacy and adoration had taken on an air of obsession, possession, and violence.

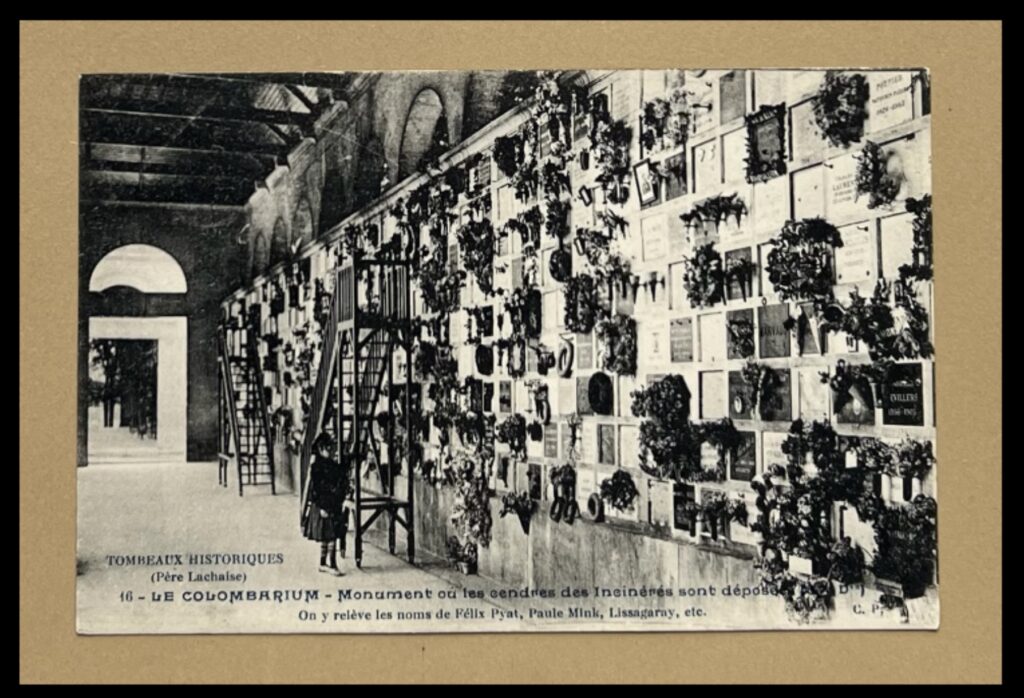

Detail of [CON_B06922_F004_029] – TOMBEAUX HISTORIQUES (Père Lachaise), 16 – LE COLUMBARIUM – Monument ou les cendres des Incinérés sont déposees. On y releve les noms de Felix Pyat, Paule Mink, Lissagaray, etc., FRANCE: Paris, Père Lachaise.

This clue uses only the latter image of the two pictured here, of a little girl standing next to a wall covered in flowers. The secret of this image is more straightforward, as the little girl is standing in the colombarium of one of the most famous cemeteries in the world, the Cimitière du Père Lachaise in Paris. What at a first glance could be a photograph of a child in a flower shop takes on a deeper, more macabre significance.

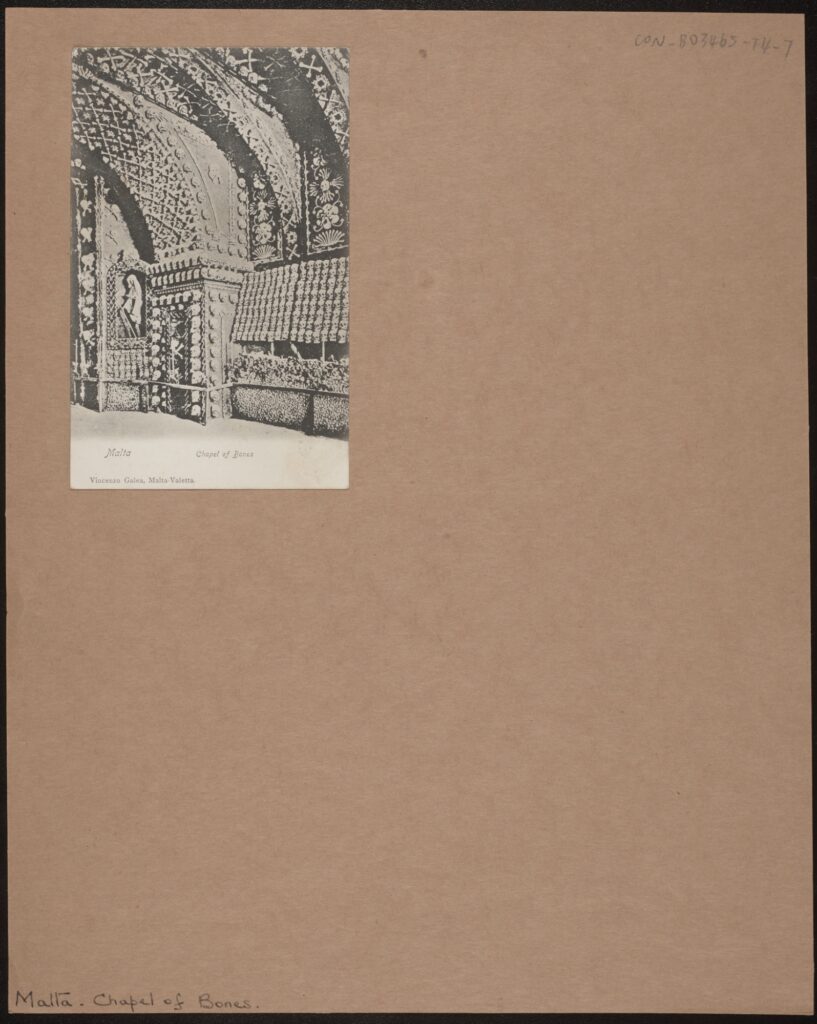

[CON_B03465_F004_007] – Malta, Chapel of Bones, Vincenzo Galea, Malta-Valletta.

I was first attracted to this photograph because of how unusual it was, in a folder full of church façades and street shots. A small, soft, black and white postcard with the simple inscription: “Chapel of Bones”. A crypt, the walls covered in skulls and bones, and one of the more gruesome photographs I’ve come across in the collection. Upon researching the site, I discovered that the chapel had been left to go to ruin, with much of its original structure lost. It is presently unknown whether the crypt still exists after years being trapped underground, and this was exactly the kind of mystery I was looking for.

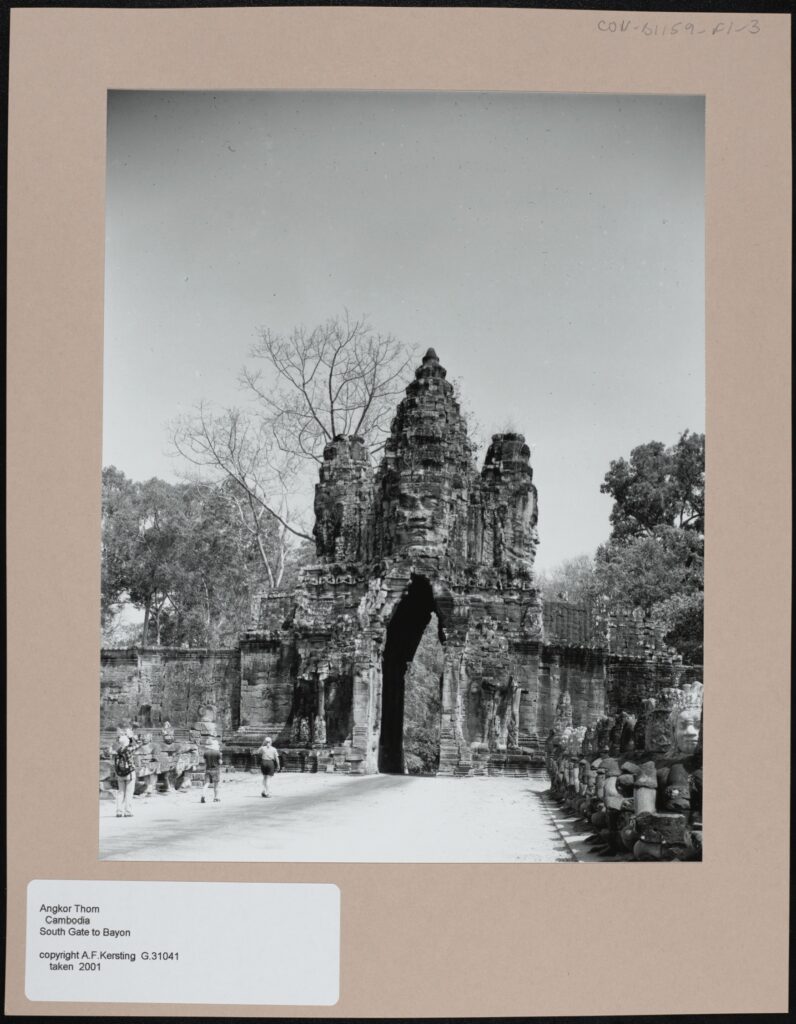

[CON_B01159_F001_003] – Angkor Thom, South Gate to Bayon. A.F. Kersting, G31041, taken 2001. CAMBODIA.

This is the final photograph that I chose, and is the most hopeful of the clues. I couldn’t not include a Kersting shot in this selection, and there was something about this one which captivated me. Taken in Angkor Thom, Cambodia, the last surviving and most enduring capital of the Khmer Empire, this photograph depicts the famous face of the city’s South Gate. What I found most mesmerising about this shot is how well the gate has survived, given that the city has been abandoned for at least 400 years. There was something quite poignant about the face of King Jayavarman VII, cast in stone, looking out over the overgrown city, and so I included this as the final clue, symbolising endurance through centuries of history.

Process

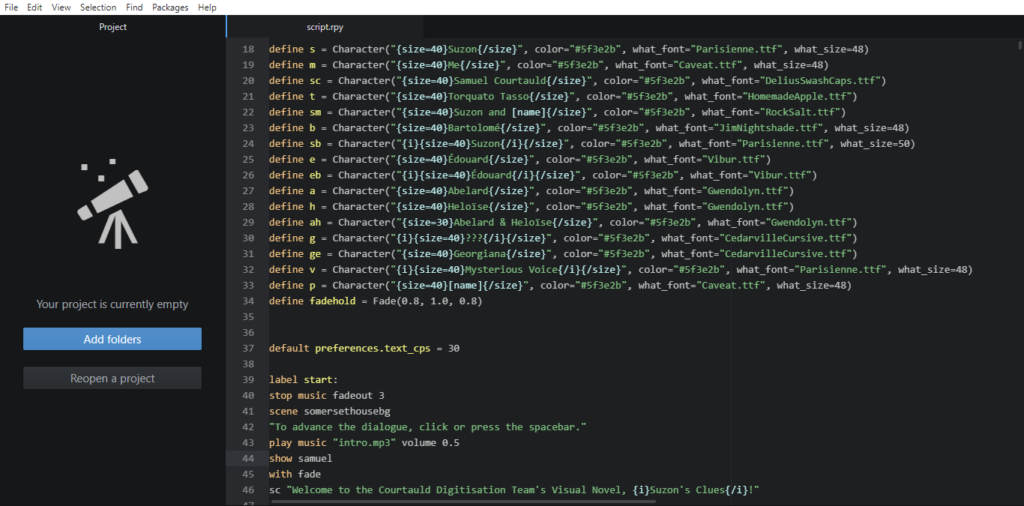

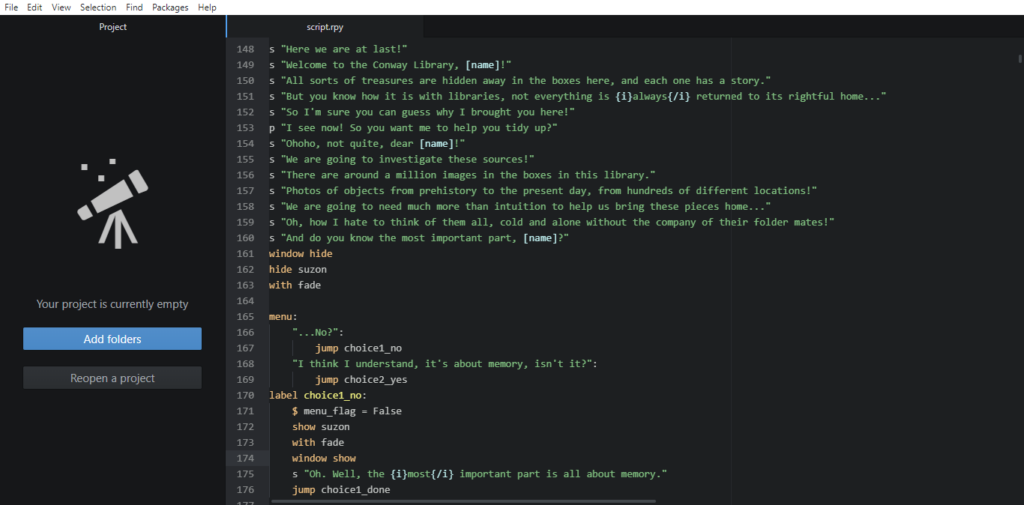

When I first started this project, although I had a pretty clear view of the finished product, the route to its completion was decidedly murkier. I had heard of several programs for creating visual novels and role-playing games, and so in the end I settled on using perhaps the most popular; a program called Ren’py. Ren’py is designed for users with minimal experience of coding, with much of the game development relying on inputting background images and props. The program works by providing a central interface for the script, and a number of folders for backgrounds, character sprites, and sound effects. A degree of knowledge of coding was required to write the script, but there were useful guides on Ren’py’s site and the wider internet. I definitely appreciated being given the time to learn some coding, as I had no prior experience.

[Some examples of code used in the game: character names and specifications at the beginning of the game. Edited with Atom via Ren’py]

[Some examples of code used in the game: opening dialogue between Suzon and the player, as well as the first choice in-game. Edited with Atom via Ren’py]

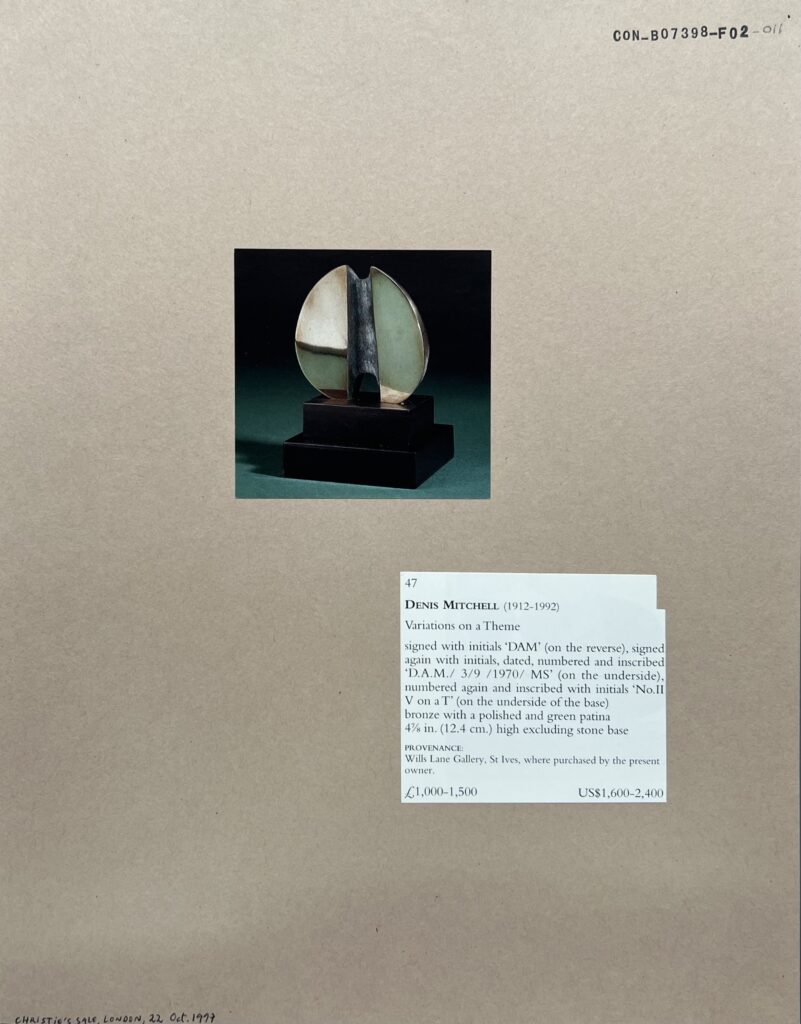

This approach suited my aim to immerse the game in the Conway’s architecture, as it allowed me to place emphasis on changing scenes, visual clues, and exploring the library. I didn’t want to overcomplicate the gameplay and end up creating a kind of decision-making labyrinth. Every standard background is an unedited shot of the Conway Library or Courtauld Institute, and many of the props were also photographed on site. For example, the original boxes belonging to each source were also photographed and used in the “Chapter Cleared!” screens at the end of each chapter.

[A few examples of some “props”, including Bernini’s bust of Bonarelli in its box, a section of carpet, a volunteer pass, and a handwritten “clue”.]

In addition to this, most of the sound effects were also recorded in the library, for example the sound of the wind heard in the demo was recorded one chilly afternoon in Vault 3, and the sound that plays when a clue is discovered is the sound of a Kersting print being flipped over. I had learnt from attending a workshop with sound artist Robin the Fog that smartphone recording apps are often sufficient for capturing audio of a reasonable quality. This is what I used to create the sound effects used in the game.

[A screenshot of the sound effects compiled here.]

Through this approach, I hope that I have injected as much of the Conway into the project as possible, I wanted to imbue the whole thing with a kind of “library flavour”. There are some photographs of Conway milestones included as well, such as the before, during, and after of the process of photographing the red boxes, and the decorations put up in the Witt Library for the Witt and Conway Staff Reunion.

[Photograph of the approach to the vaults, taken before, during, and after the photographing of the red boxes, photographed by the author.]

[Photograph of the Witt Library, taken shortly after the Witt and Conway Staff Reunion, photographed by the author.]

Once the sources were selected, the next step was to obscure them. I wanted to create a kind of puzzle where the player would have to learn more about their item in order to locate its box, “bring it home”, and advance to the next chapter. So, after the research I compiled a selection of facts about each object. For example, with regards to our first problem, the bust of Costanza Bonarelli, its first clue relates to location and time; a map of 17th Century Siena. The bust was created in the 17th Century, and Costanza herself was originally from Siena. Next, a poem from well-known poet of the Italian Renaissance, Torquato Tasso, included for the line “not that I hope for anything from you, my sweet life, except misery”. This is a reference to the tumultuous affair between Bonarelli and sculptor Bernini. Next, after some exploration, a dagger is discovered in the vault, making an obvious reference to the dagger that was used to disfigure her. From here, almost at the end of the puzzle, Suzon and the player follow the sound of music, which gets louder and quieter depending on how far away the player is as they move through the Conway. The music is an aria from Handel’s cantata, “Apollo e Dafne”, which references Bernini’s most famous work, Apollo and Daphne. This is the final clue which connects Bonarelli and Bernini. From here, the player is given a choice of boxes and, when the correct option is chosen, the item is returned to its home, and in a sense is laid to rest.

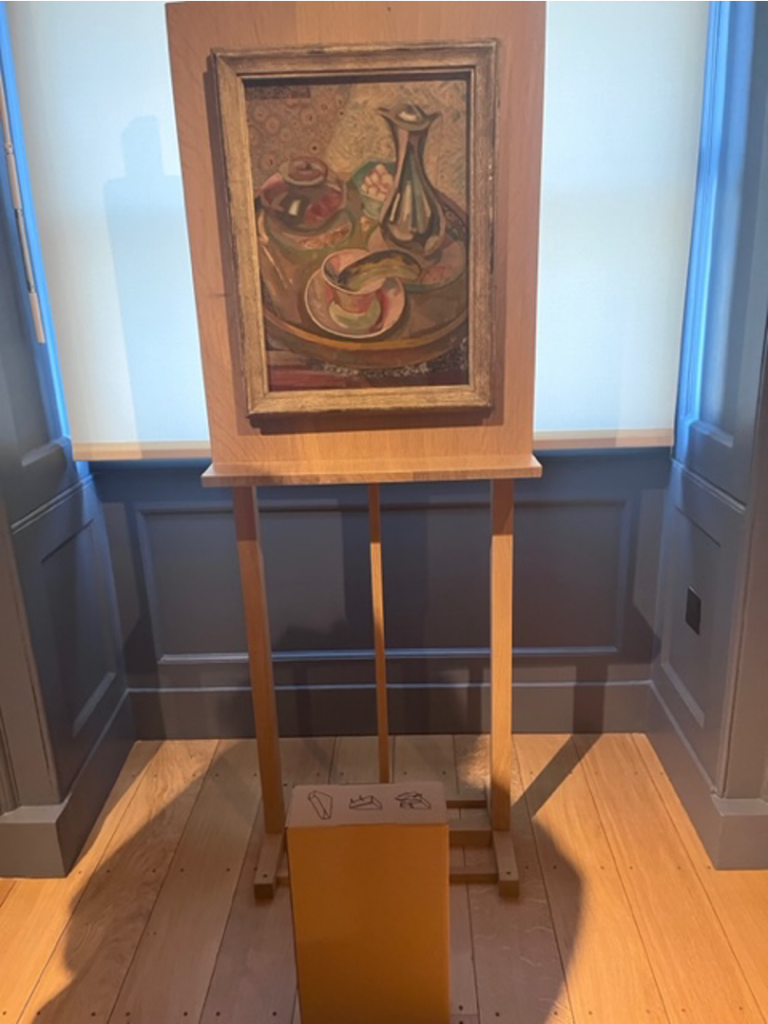

This formula is followed for the remaining sources, with some variations. I wanted to try to make the sleuthing process as varied as possible, taking advantage of different forms of media. It seemed like to do otherwise would be a waste when Ren’py allows for the integration of text, pictures, and audio. Another benefit of this approach is the inclusion of a number of characters to further enrich the experience: There is Suzon, of course, who many will recognise from the painting, “A Bar at the Folies-Bergère”, by Édouard Manet, who also makes an appearance. Torquato Tasso arrives to read his poetry, and the vaults are frequented by a ghost by the name of Georgiana. She is named after the Spritualist and artist, Georgiana Houghton, subject of an exhibition at the Courtauld Gallery entitled “Spirit Drawings” in the Summer of 2016. By including Georgiana, Suzon, Manet, and indeed a short cameo from Samuel Courtauld in the introduction, the Gallery, Institute and Library are all represented in the gameplay.

[A photograph of Suzon in situ, photographed by the author in the Courtauld Gallery, Strand, London, December 2022.]

Testing and Launch

Once the chapters were written, the script, images, sound effects and music were all combined within the game directory provided by Ren’py. I had, perhaps naively, thought that the bulk of the work was finished, but as always when using unfamiliar technology, there are going to be a few hiccups. The music or sound effects come in too early, too late, too loud, or too quiet. One character sprite fills the entire screen, another doesn’t show up at all. After a couple of weeks and many hours of rewriting code, the game finally ran successfully. I must extend my gratitude to my fellow interns and staff in the Conway Library for playing through the demo and providing some much needed feedback: it’s always helpful to look at these things with as many sets of eyes as possible! It was also fun seeing everyone’s reactions to the experience of moving around the library in-game, and I’m happy that this was well-received.

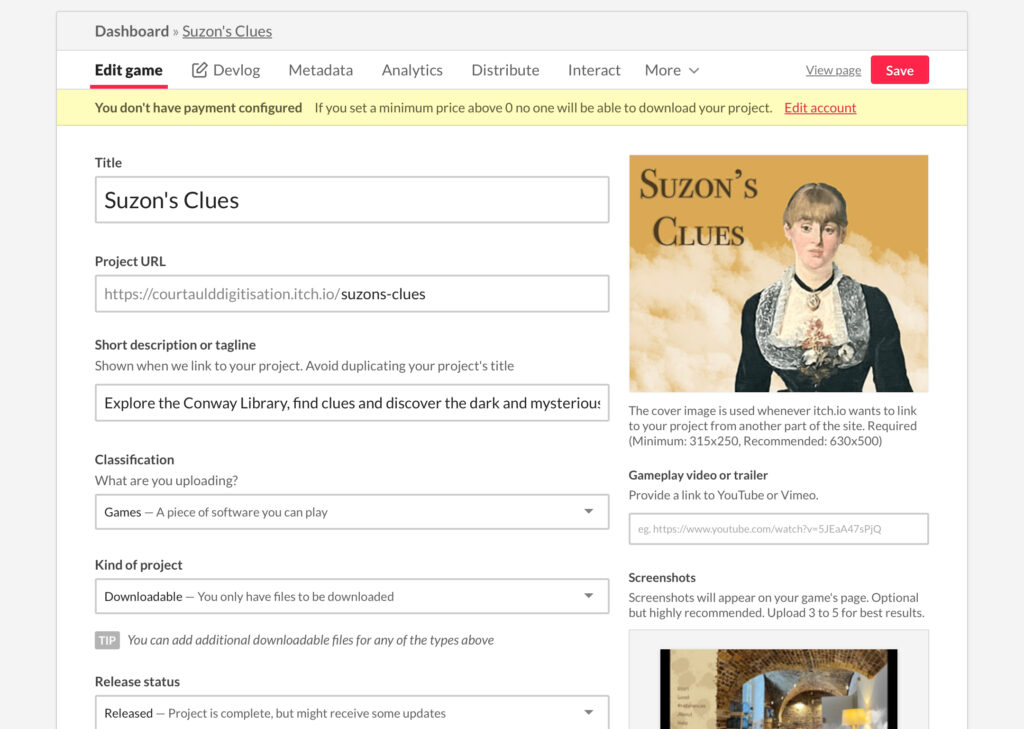

Once the testing was over and everything was tidied up, it was time to finally launch the game. Suzon’s Clues is hosted on the independent game developer site, itch.io: Suzon’s Clues on itch.io.

[A screenshot from the developer’s page of “Suzon’s Clues” on itch.io, depicts title and cover art.]

[A screenshot from the developer’s page of “Suzon’s Clues” on itch.io, depicts the uploads of the game files.]

Once the content warnings, game description, installation instructions, and game file were uploaded, everything was done. It was strange to stop working on this project, at times it felt like it would never be finished! I felt that I would always be writing new mysteries for Suzon and whichever unwitting volunteer she had managed to capture, and certainly felt some sadness writing the final scenes.

Conclusion

The aim of Suzon’s Clues was, in part, to explore the ways in which we can interpret the pieces in the collection. Are they to be used to understand the processes and inspirations of sculptors, painters, architects, and photographers? Can we use these photographs to understand social, cultural, and political trends? What about making statements about which objects are preserved, and why? Are they a collection of pictures that are nice to look at? Of course, all of these are true.

The photographs in this collection are preserved with varying degrees of detail, and it would be a truly gargantuan feat to attempt to research the mysteries of every last piece. What I hoped to achieve with the tiny number of sources used was to demonstrate the sheer amount of information that is just waiting to be discovered within these boxes, and the intrigue and fun we can have if we attempt to unearth them. Further to this, Suzon’s Clues is something of a love letter to the Conway Library. So much more than just a building; it is a centre of memory and has been the home of the collection. More than that, the Conway has been the beloved workspace of hundreds of volunteers, staff, students, and visitors. I hope that I have been able to capture a sense of the experience of working on this project, and working in this space. Whether we are sorting through Kersting prints on the mezzanine, poring over masters at the table on the bottom floor, or digitising it all in the vaults.

When I first arrived in the Conway Library in Summer 2022 I was almost overwhelmed by the size of the collection and the methods of telling its story. We as interns have all been given so much freedom to run with our ideas, which has been both deeply rewarding and tremendous fun. Happily, I think we will all leave with new skills and very fond memories.

Rosa Coomber

Courtauld Connects

Digitisation Project

Digital Narratives and

Storytelling Intern

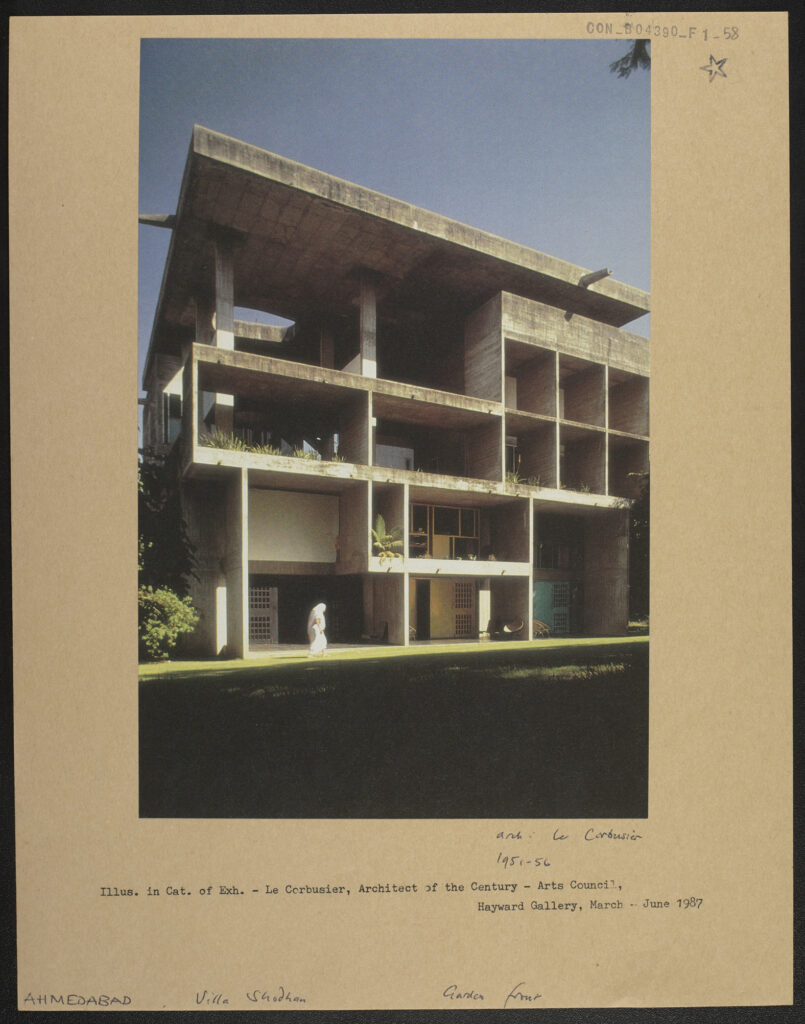

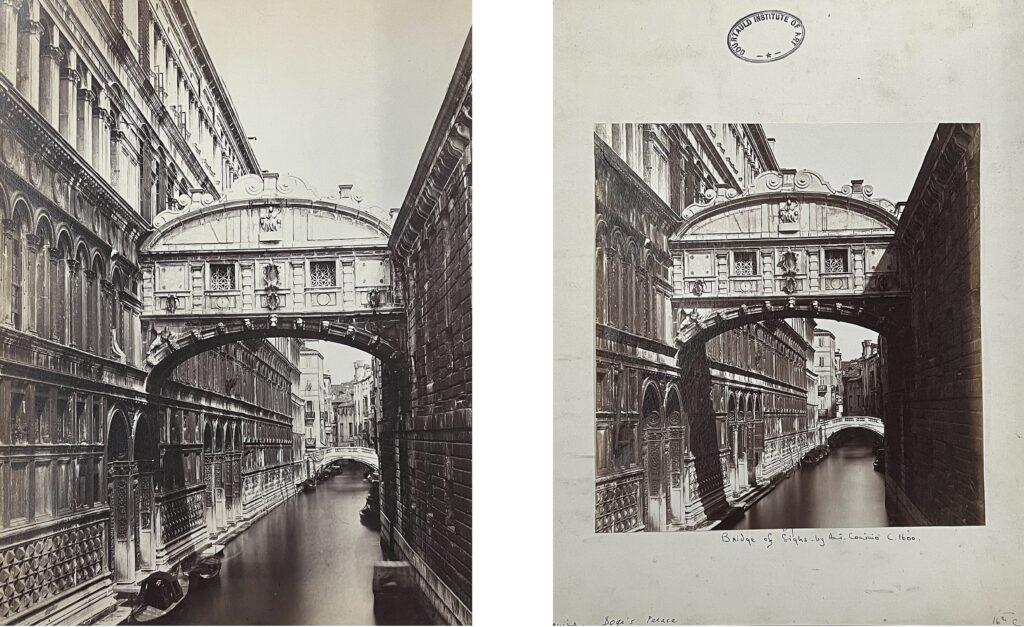

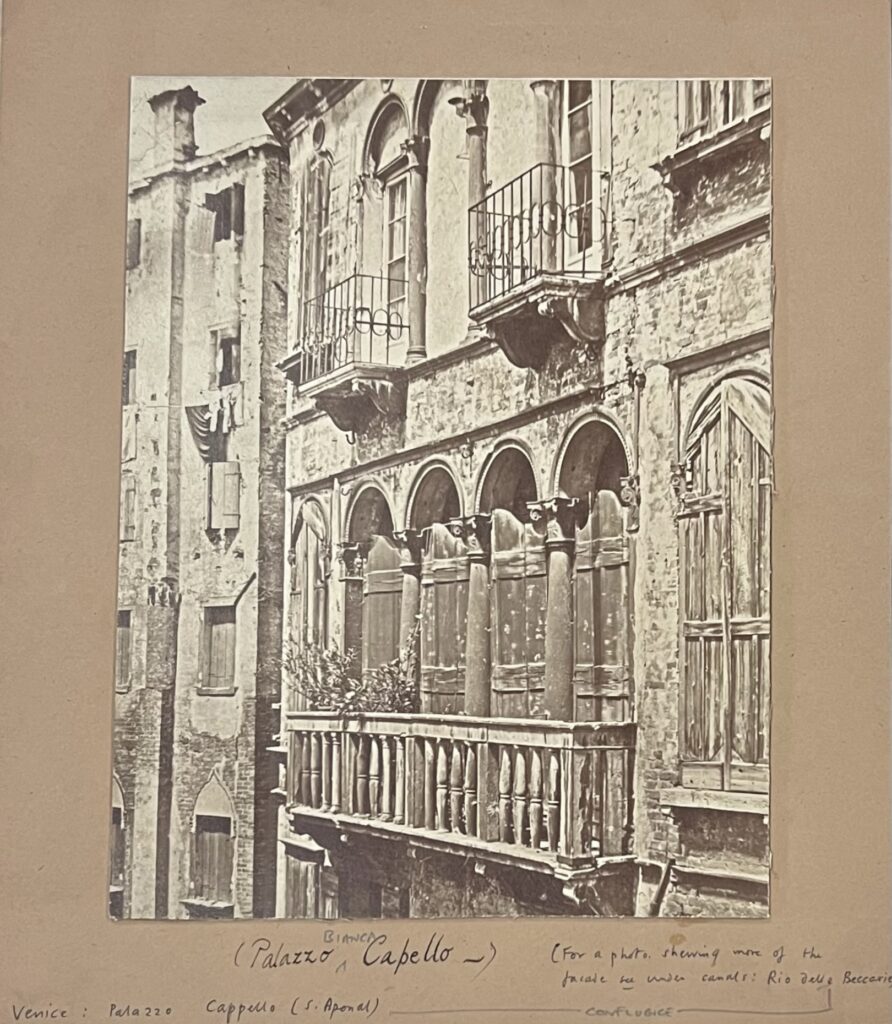

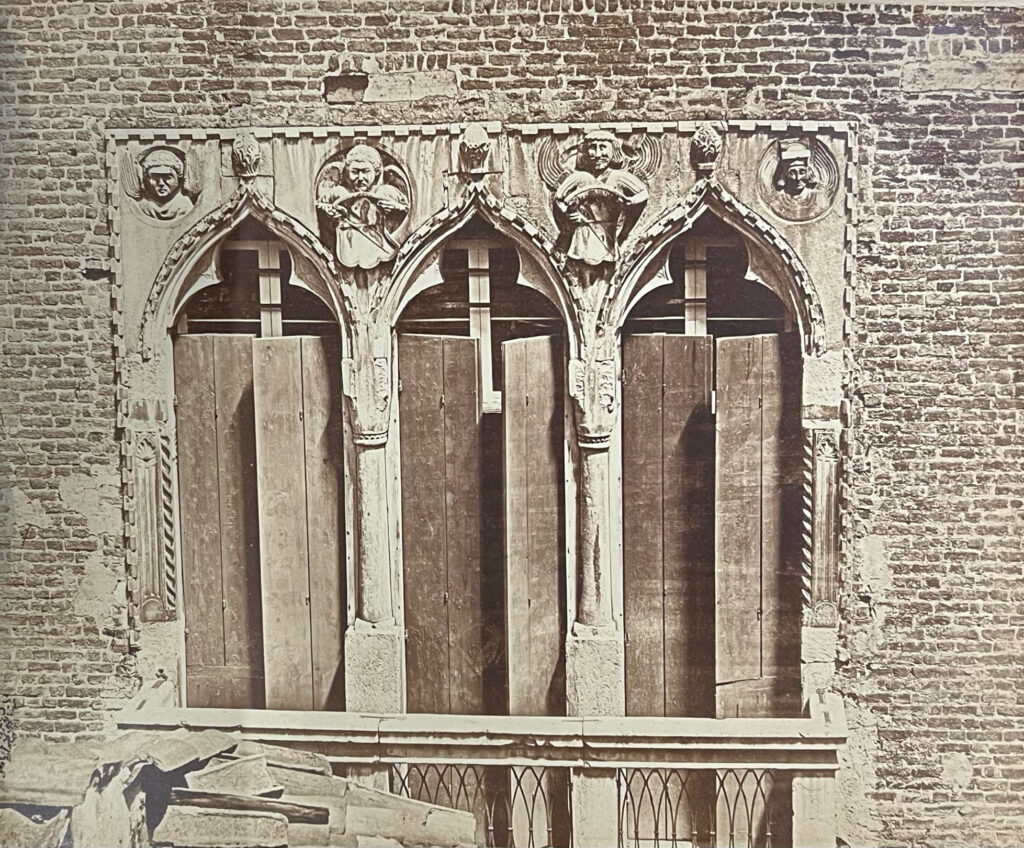

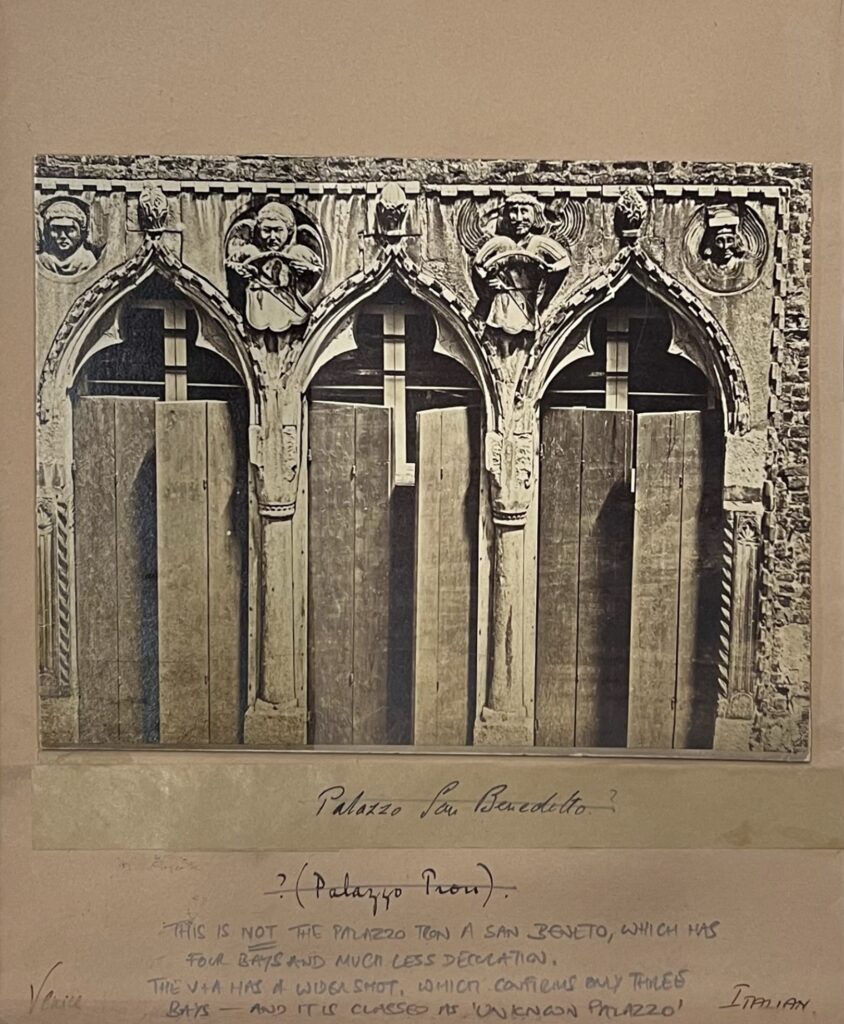

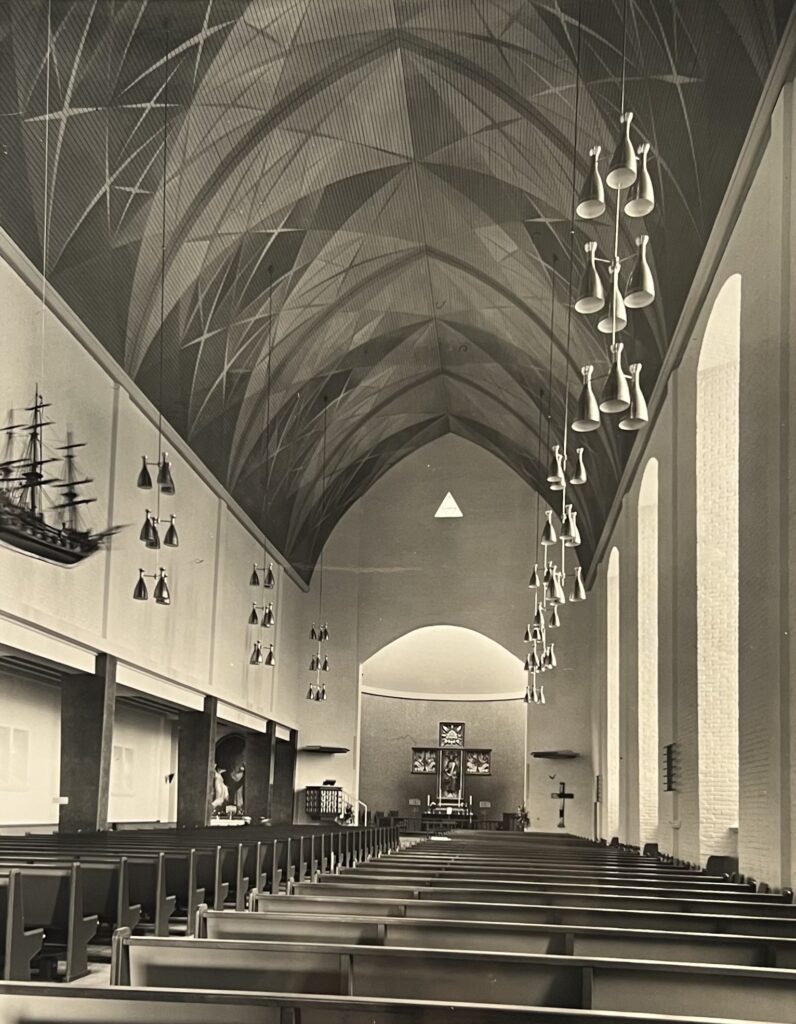

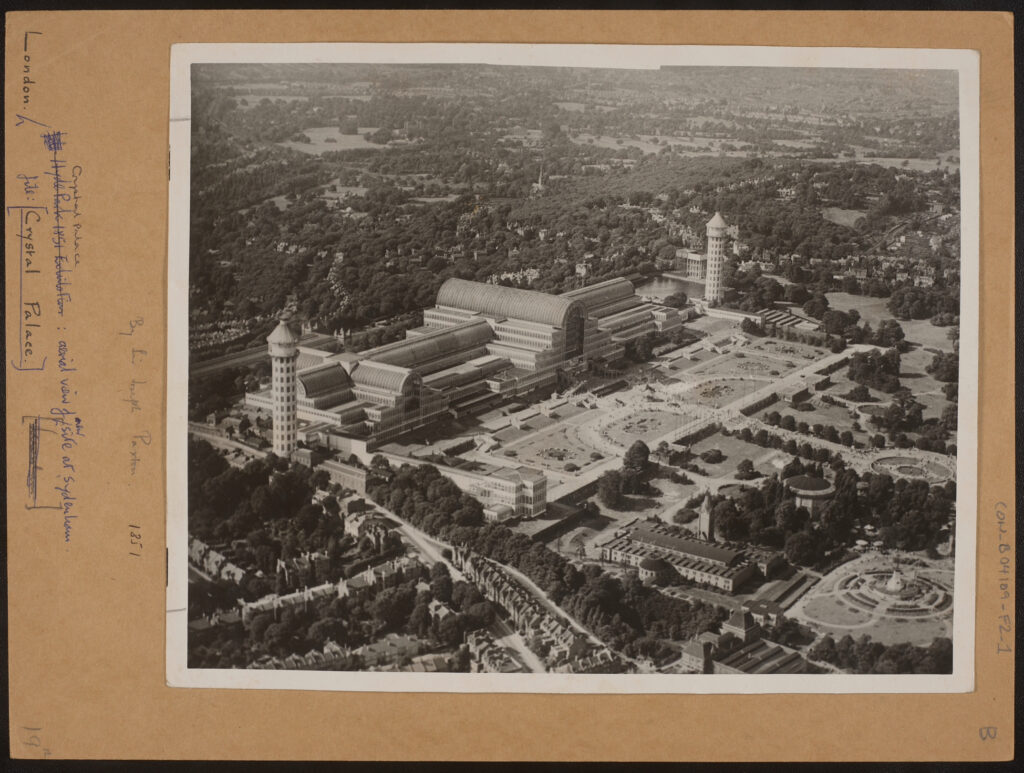

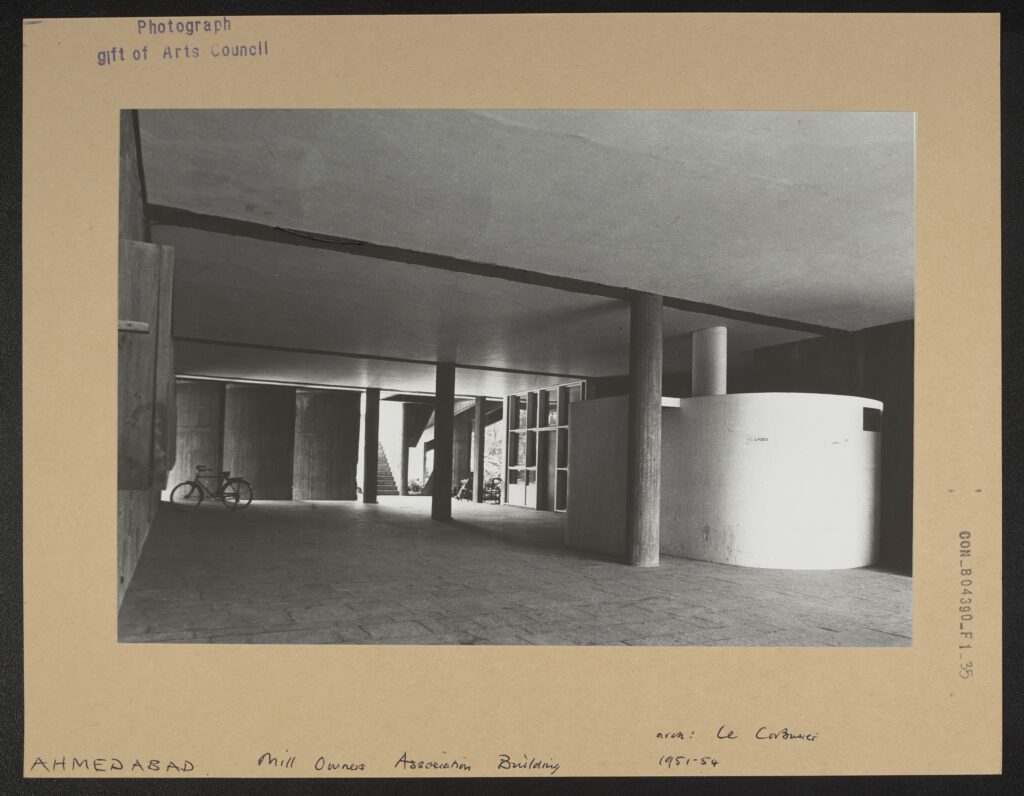

CON_B04390_F001_035

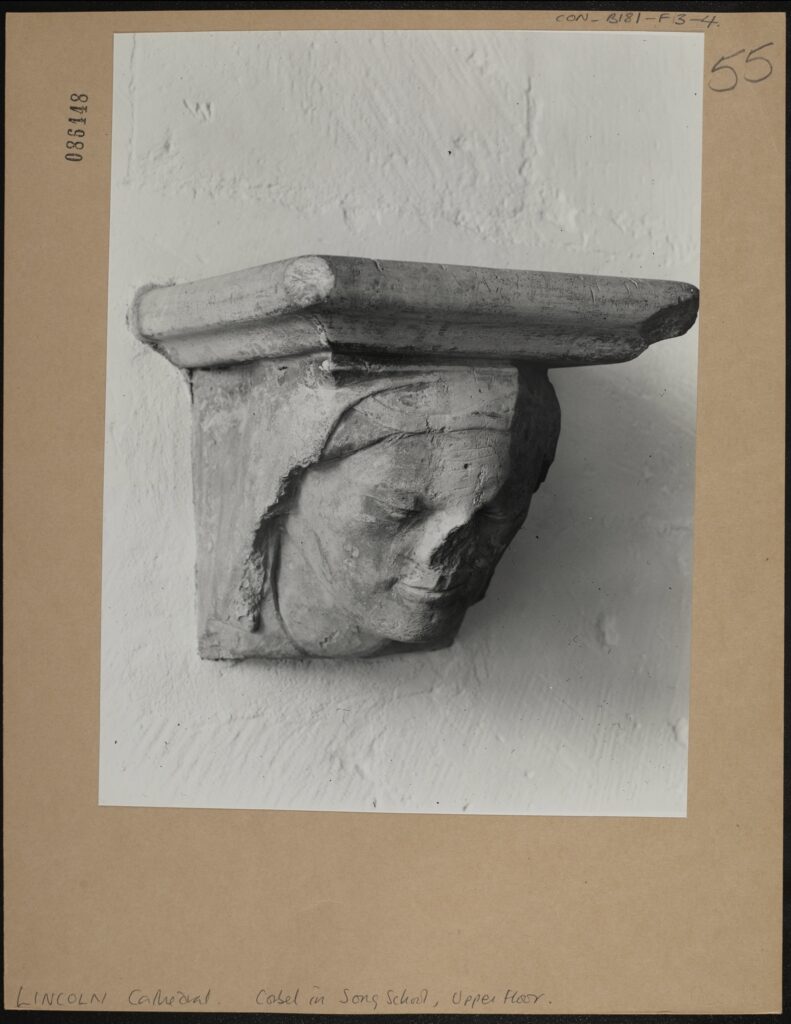

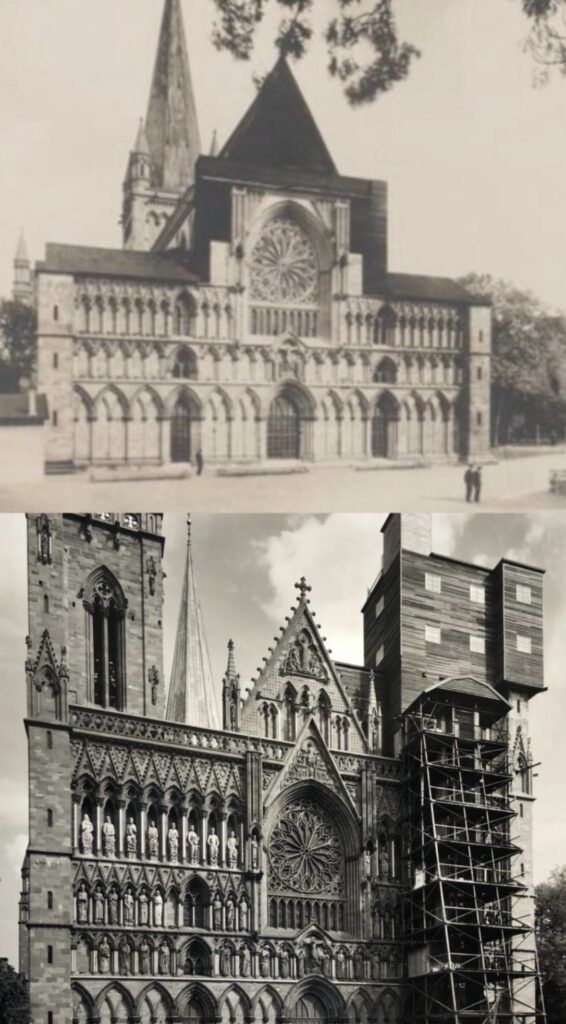

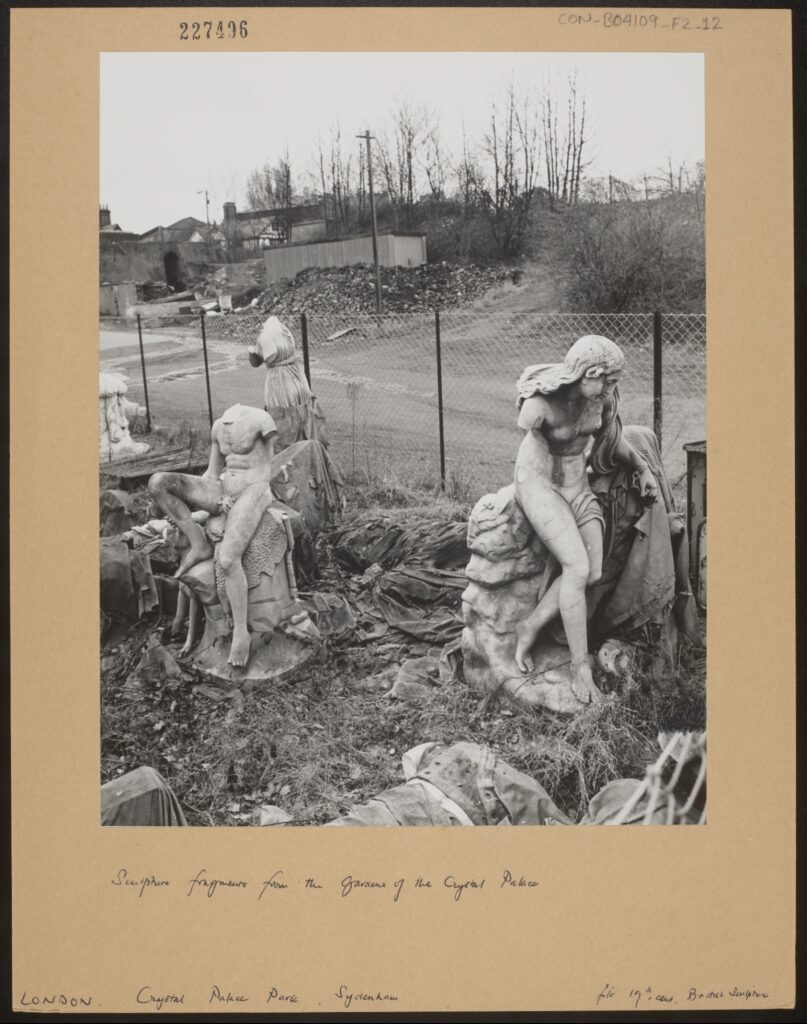

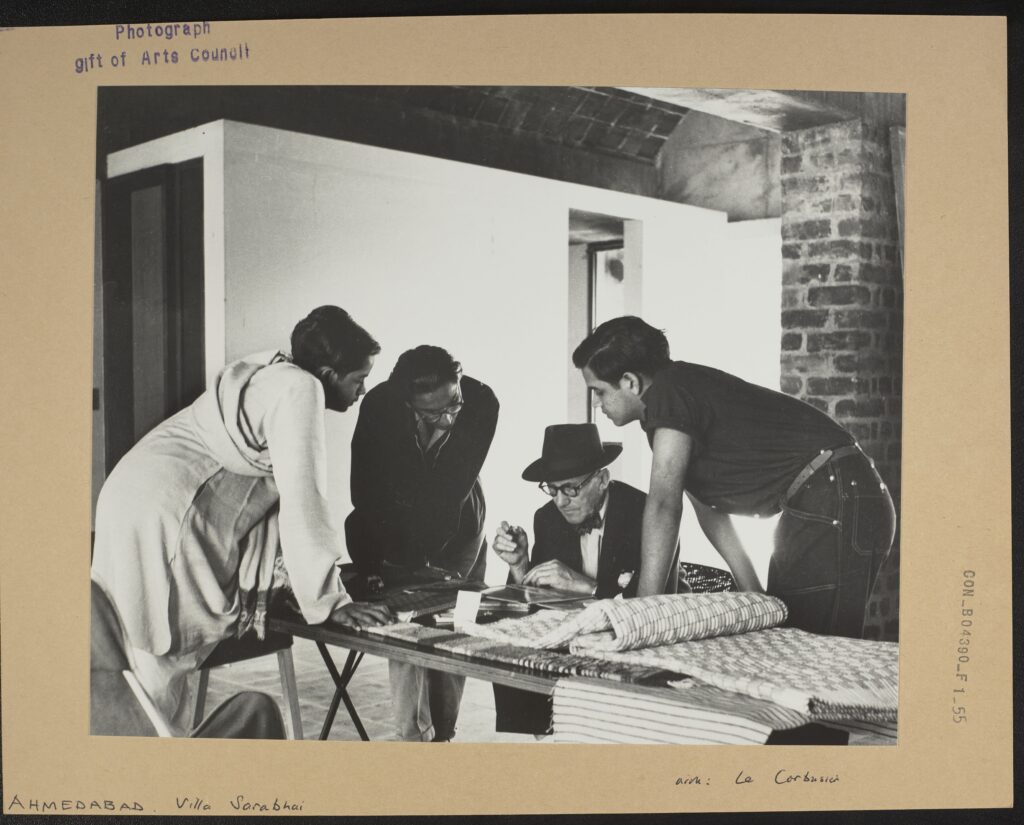

CON_B04390_F001_035 CON_B04390_F001_055

CON_B04390_F001_055