A beautifully carved tool, The Courtauld’s loom pulley would have been used for weaving textiles.

A Male Dominated Craft

This carved object called a heddle pulley, would have been an essential tool in the loom of a Guro weaver. A pair of heddles, which are opened and closed during the process of weaving, would have been suspended from this pulley. Amongst the Guro, as in most of West Africa, weaving has historically been and largely remains a gendered form of work. Undertaken by the men in a family, boys learn from their fathers, uncles or older brothers and women are prohibited from practising the craft. Having mastered the necessary techniques, a young man would, in turn, pass these skills onto his own sons, nephews or younger brothers. Depicting an idealised female face, the pulley would have hung very near the craftsman’s gaze, allowing him to reflect on something beautiful while he worked.

Decorating the Loom

The looms used for Guro weaving can be built directly into the ground or carpentered so that they are portable. A loom pulley, decorated like the one in The Courtauld‘s collection, would then be hung from the upper struts of the loom as a means of suspending the heddles that control the opening and closing of the warp threads. An integral part of the loom, such a delicately carved pulley would have hung intimately close to the craftsman’s face. An object of beauty upon which the weaver could reflect whilst working, Guro weaver Boti bi Yuan, shown at his loom here, said in an interview of 1984 “When you work it is very pleasant to see something nice in front of you.”[1]

Designing Guro Clothes

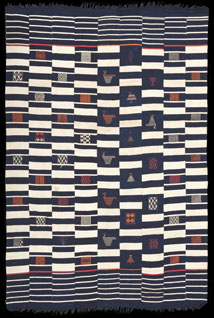

Guro woven textiles are part of a broader West African tradition of cloth production, in which narrow strips measuring between 1 and 45 centimetres are stitched together to produce larger cloths.

Each individual strip often features a number of patterns that are either geometric or figurative. Thoughtfully arranged and sewn together, these narrow strip textiles offer an extraordinary range of possible visual effects. Designs show innumerable regional and stylistic variations, as well as reflecting the personal taste of the individual weaver and patron.

Historically Guro cloths would have been most commonly executed using white, indigo and red cotton, produced and dyed locally. The increasing availability of synthetic dyes and commercially produced cotton and acrylic yarns since the middle of the 20th century have allowed for a much wider spectrum of colours to be incorporated.

Valuable Cloth

In the past Guro textiles would have been principally used as clothing, with everyday clothes made from plain textiles and intricately woven prestige pieces kept for festivals or other special occasions. Today their use during special occasions predominates. Woven textiles also form part of a woman’s dowry and are used in funerary rites to wrap the body, place in the tomb and as gifts to the family of the deceased. Masquerade costumes are often made from woven textiles. Textiles also play a role in dispute resolution, when gifts of cloth may be presented as a gesture of reconciliation from one party to another. Despite changes in the status of weavers throughout the 20th century Guro textiles have retained their value as an item of local and long distance trade.

1. Eberhard Fischer (2008). Guro- Masks, Performances and Master Carvers in Ivory Coast (Munich: Prestel) p. 475

Back to West African Loom Pulley