In Renaissance Italy, naturally-occurring stones and minerals, such as chalcedony and agate quartz, were marvelled at for their swirling, variegated patterns of colour. This was part of a wider fascination with natural phenomena in the 16th century. Renaissance curiosity cabinets or Wunderkammer contained examples of natural stones – cut, polished, set with golden mounts, and presented alongside other items from the natural world; stuffed animals, seashells, skeletons and corals, for instance.

The wonder of stone

The glass industry was keen to devise a convincing substitute for highly-prized natural stones, as they could be made to meet the demand for such natural wonders at a lower cost, and the famous glassmakers of Murano, Venice, were successful in this quest. The Venetian scholar and historian, Marcantonio Coccio Sabellico wrote in his De situ Venetae urbis(published around 1495) that ‘there is no kind of precious stone that cannot be imitated by the industry of glassworkers, a sweet contest of nature and man.’

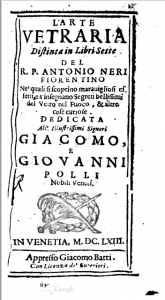

The hard work that went into creating imitations of nature demonstrated to Renaissance buyers the skill, intelligence and artistry that humankind could achieve. It would have surely seemed like magic to see glass resembling stone to come out of workshops at the hands of men. Antonio Neri’s L’Arte Vetraria (‘The Art of Glass’, a collection of Venetian glassmaking recipes) of 1612 describes the beauty of a piece of glasswork in the following terms: ‘it will seem as if nature herself could not arrive to the like perfection, nor art imitate it’.

The added value of the human touch

Calcedonio glass, named after chalcedony quartz, is an example of glass made to imitate minerals. Its swirling patterns and brown, murky colours are reminiscent of hard, polished stone. To achieve such an aesthetically pleasing final product required a labour-intensive process. Metal oxides, such as silver, tin, iron, copper and mercury, were added to the moltentransparent glass base, and would be deliberately roughly mixed to create a marbled effect. It may seem ironic that such a difficult and labour-intensive process was required to imitate stones which existed in the natural world, but glassware was continually available, unlike stone which had to be mined, and could therefore meet demand much more quickly. In addition, the skilled craftsmanship itself added to the value and made the work all the more prized, ‘this chalcedony was made so beautifully and finely that it resembled real Oriental Agate, and in the beauty of its colours, far surpassed it… [the process] is laborious and takes time, but results in something magnificent.’ The high price demanded by chalcedony glass is seen in a commission of eleven chalcedony vases in 1475 by the great Florentine banker and statesman Filippo Strozzi, who paid the handsome figure of fifty-five ducats.

Long before major industrial or technological revolutions, nature was the producer of all that was beautiful and perfect in the world. It was a marvel to own something man-made that rivalled the previously incomparable beauty of the natural world, as it demonstrated the supremacy and skill of human ability.

Back to A Venetian Chalcedony and Adventurine Glass Bowl

Bibliography

Barovier Mentasti, R. (1983) Glass in Murano. Venice: Veneto Region and the Venice Chamber of Commerce.

Edwards, G.R. and Sommerfeld, G. (1998) Art of Glass: Glass in the Collection of the National Gallery of Victoria. Melbourne: National Gallery of Victoria.

Higgott, S. (2011) Wallace Collection Catalogues: Glass and Limoges Painted Enamels. London: The Wallace Collection

Neri, A. (1612) L’Arte Vetraria. Nella Stamperia de’Giunti, Florence.

Sabellicus, M.A. (c.1495) De Situ Urbis Venetae