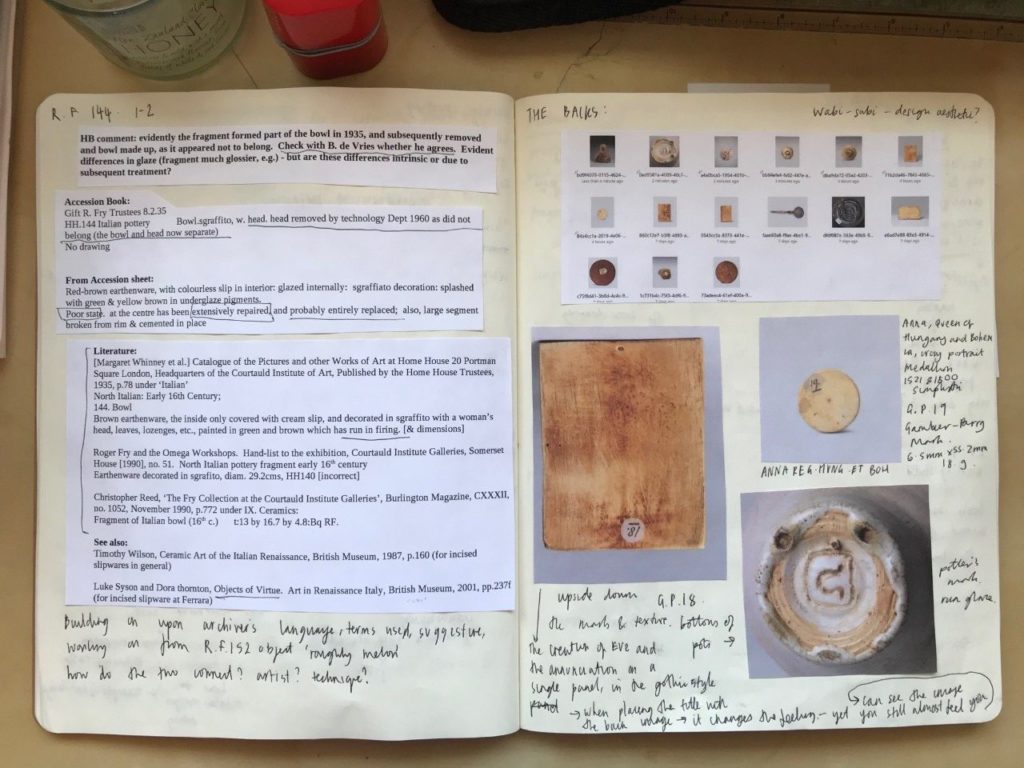

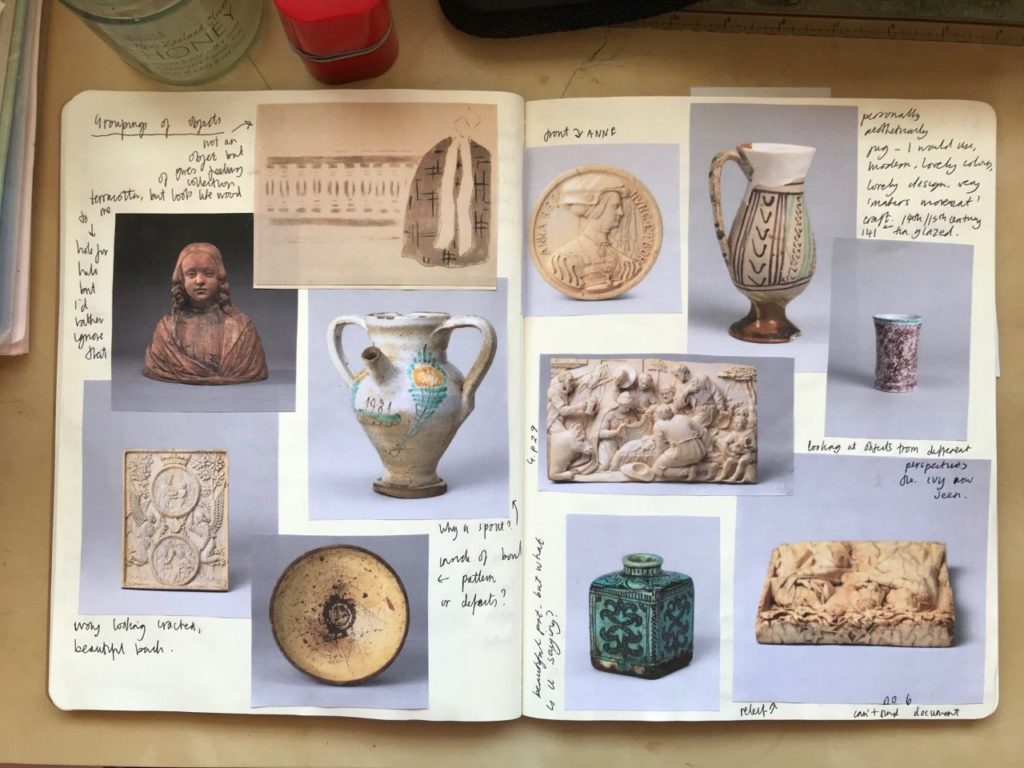

Selection Process

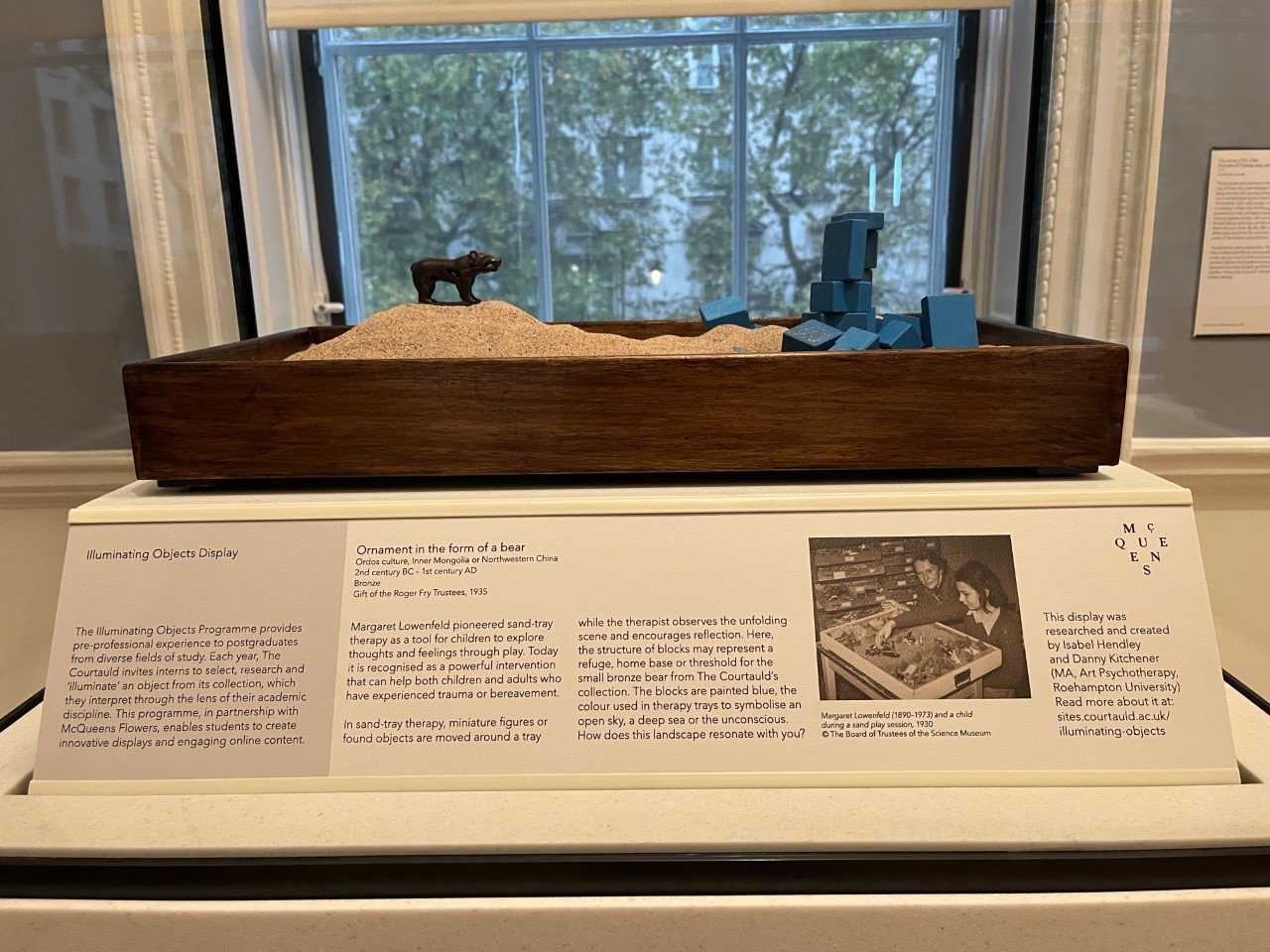

We spent some time with various objects in the store room during the selection process. Each object provided a different perspective to view art therapy with and endless questions to explore. In the spirit of our training and the clinical skills we developed, we hoped to keep our ideas open and to flow to allow for the unknown rather than jump quickly to interpretations and categorisations of the objects. Out of the six we selected, the bronze bear was the object which gave us the most space to be open and play with the project. The bear also encouraged us to bring into discussion concrete examples of creative art therapies incorporating objects in sessions, such as sand-tray therapy.

Clockwise from left to right: German pearwood pyx 16th Century; Russian amber casket late 17th Century; French Enamel Pyx 13th Century; Bronze ornament in the form of the bear 206BC-220AD; 1963 Bronze casting of The Scream (Le Cri) by Auguste Rodin, 1886.

Play

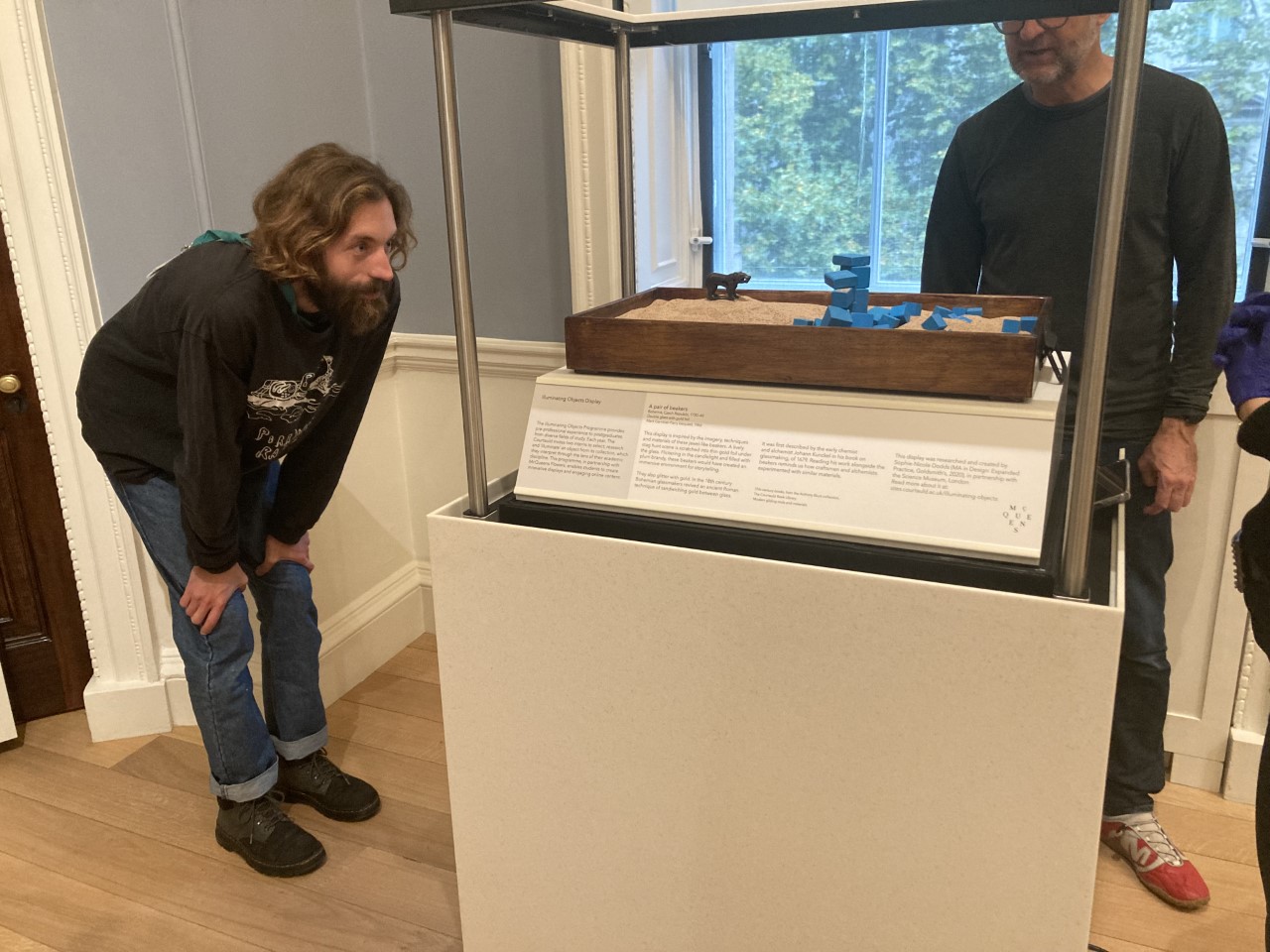

Through play, children learn about the world and their part in its unfolding narrative. Play forms a crucial part of early development as it improves social skills and physical and emotional well-being. Children learn how to communicate and collaborate with others. This illuminating objects internship was the first of its kind, as two participants worked together. As we narrowed the object down and decided to make a play-themed display utilising a sandtray, we knew we should be playful throughout this internship and create as much opportunity to experiment and play with the bear.

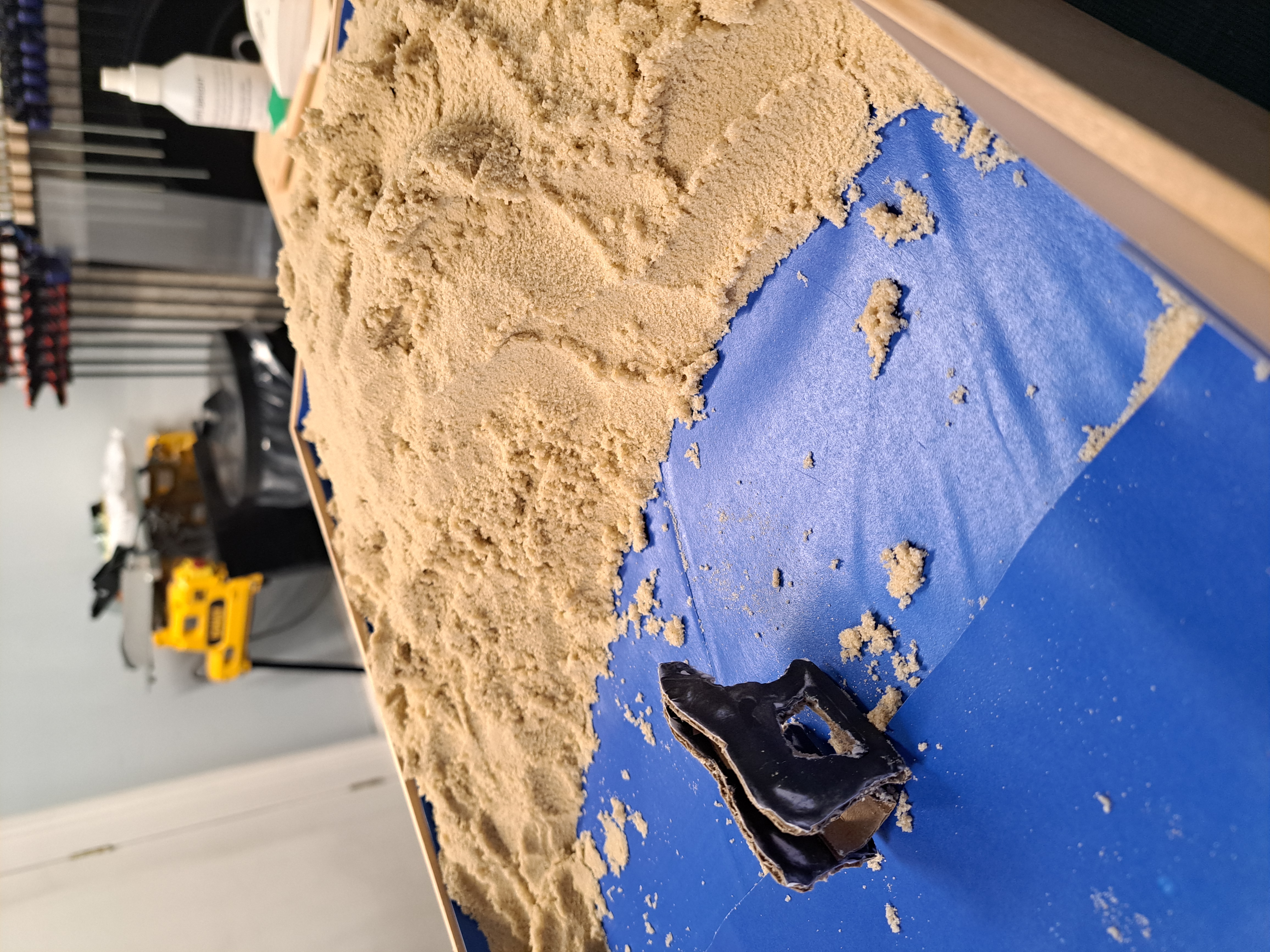

First Experiment

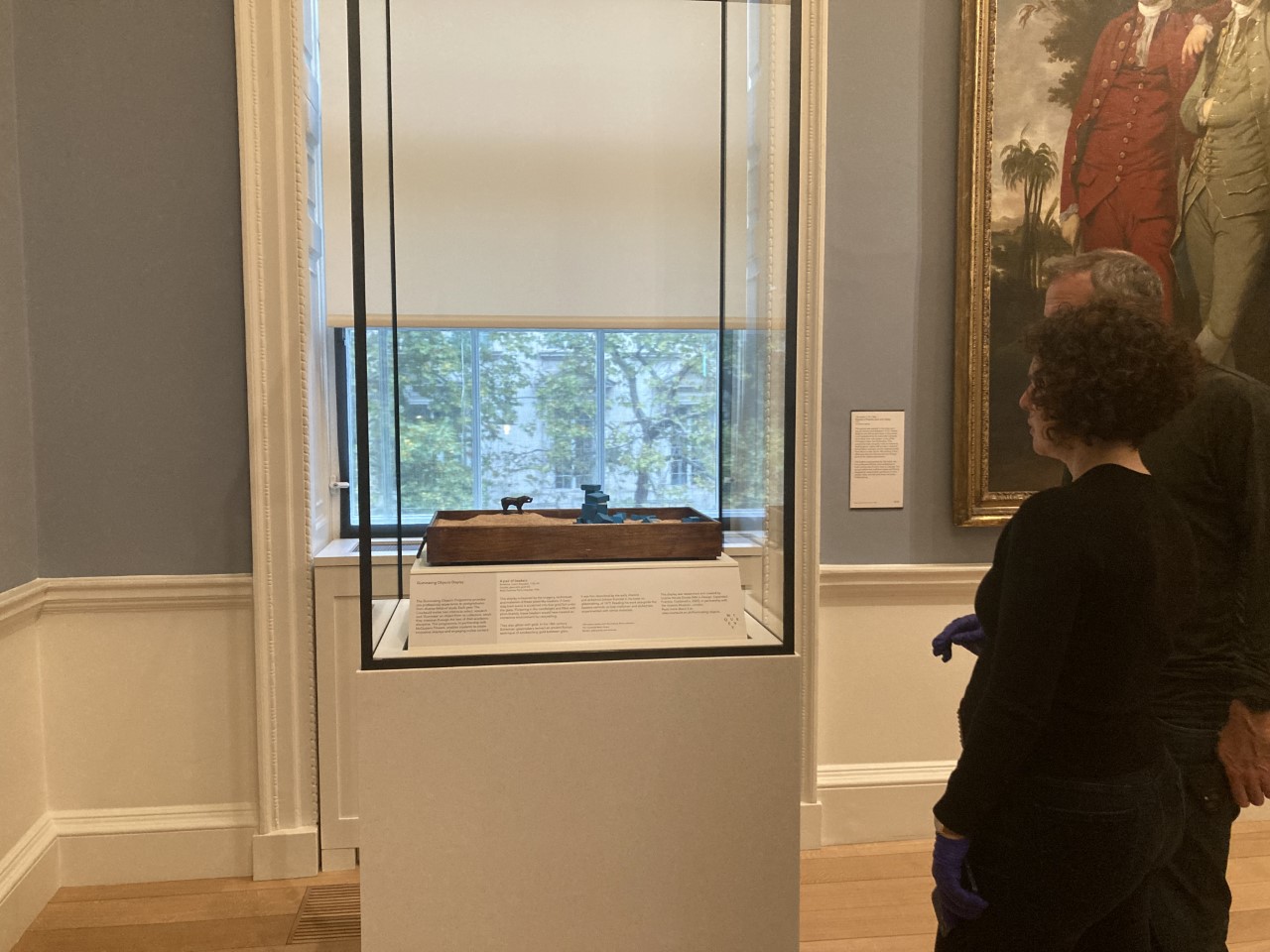

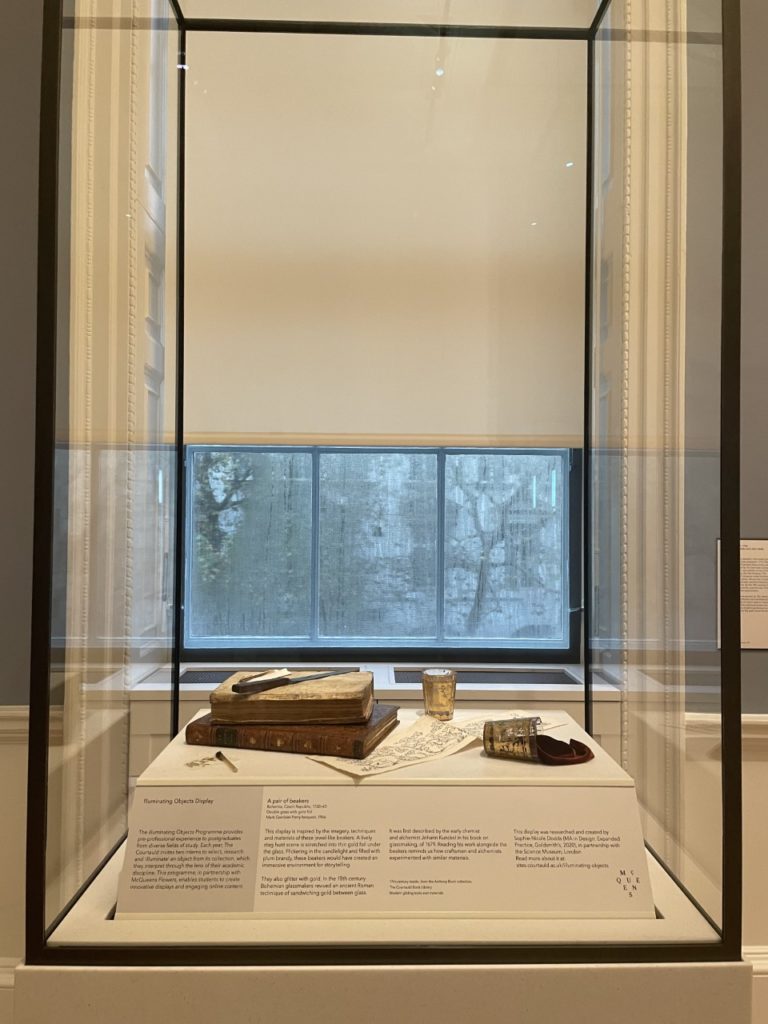

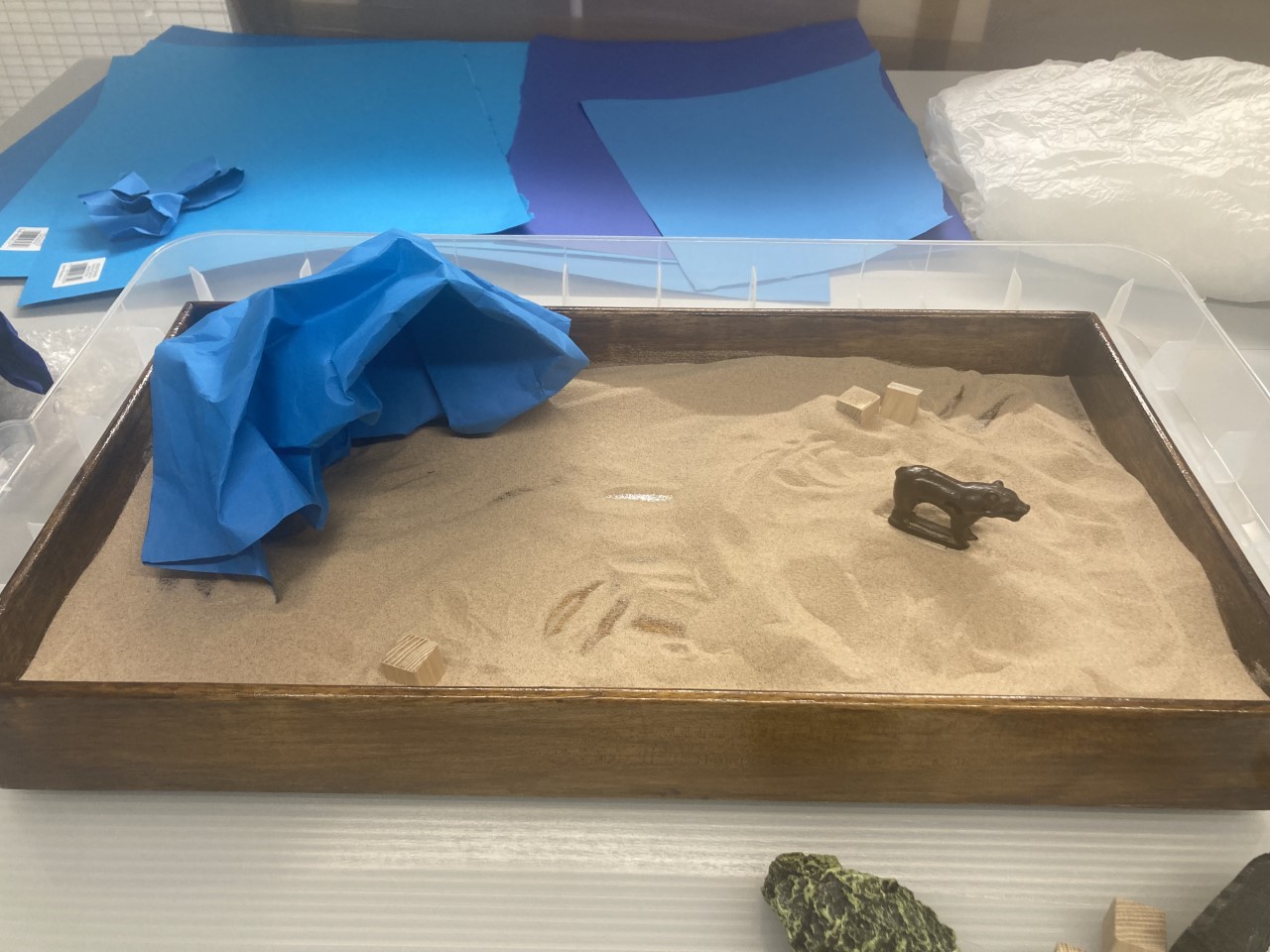

Matthew Thompson, the Courtauld Gallery’s technician built us a prototype tray to fit the dimensions of the display cabinet in the Courtauld Gallery, which Danny and I roughly measured. Usually, sand trays are longer and broader, but the wooden prototype worked just fine for experimentation. Set up in the workshop, blue paper lined the bottom and sides of the tray, and we poured some kinetic sand, often used in sensory play, into it. Immediately my instinct was to sweep my hands through the sand, which was cool to touch and absorbent. Danny improvised by making a model of the bronze bear out of cardboard to perform its duty, as we could not access the store room where the bronze bear was kept safe that day.

We spent some time moving the sand around the base of the tray. I had the urge to press down the sand around the edges of the tray, creating a pool or open terrain for the bear to stand on. The calming sensation of moving the sand around and the contained environment of the tray – a little world in itself – opened me up to play and try things out. We looked around the room to incorporate other objects for the bear to interact with. In an early experiment, Danny placed another object from the Decorative arts and Objects collection concerning the bronze bear, a German pearwood pyx. This was to demonstrate the imaginative ways of relating using any object or figure in sand-tray therapy. To play the Pyx, we found a glass jar which I filled with sand and submerged into a sloping landscape.

After this experiment, we realised that although the porous nature of the sand is a powerful way to contain feelings, it would be a damaging environment for the ancient bronze bear due to its dampness. We had to find drier sand and determine whether the bear could exist in the sand tray or needed other objects to relate to, like the Pyx.

Written by Isabel

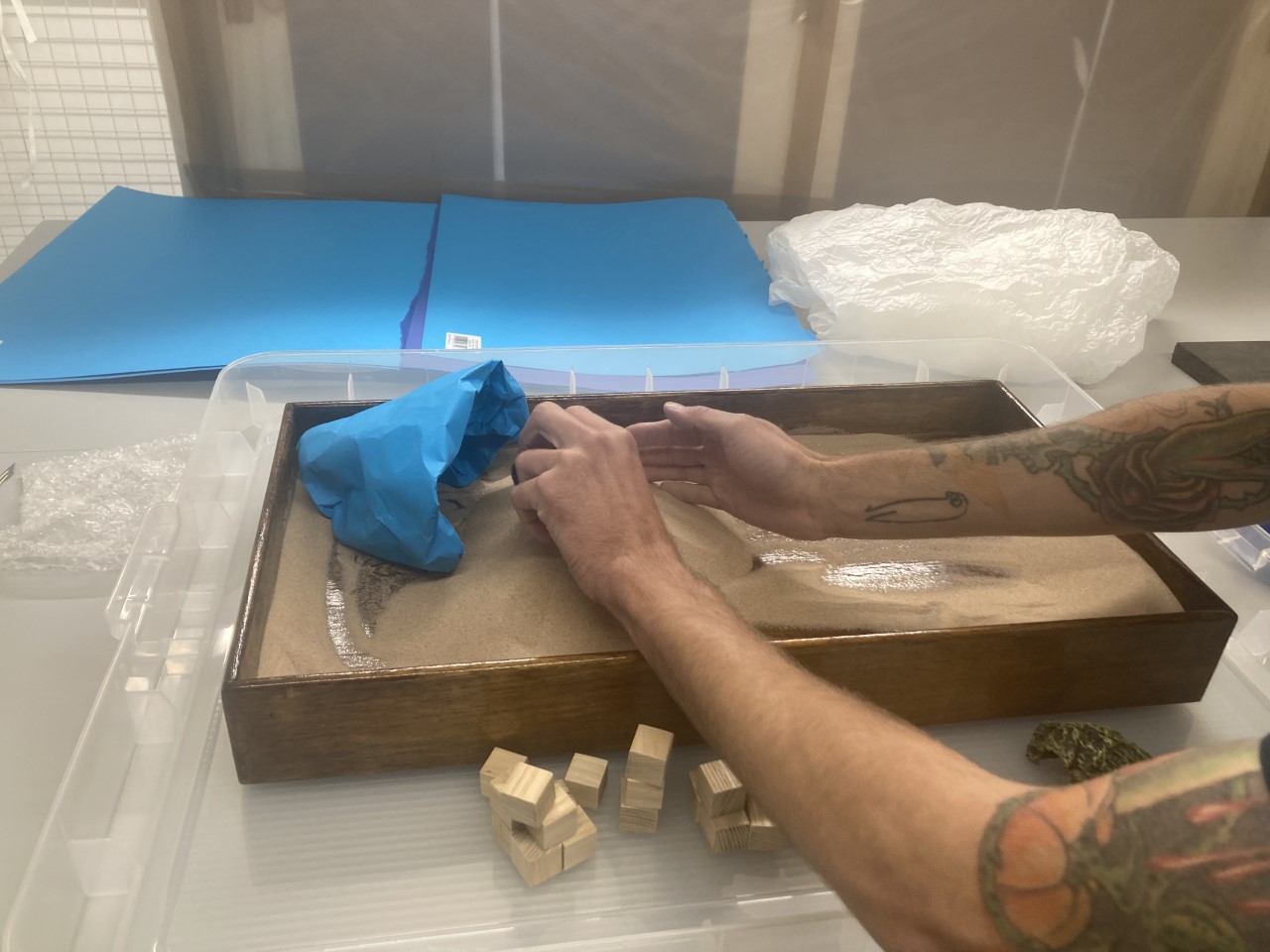

Second Experiment

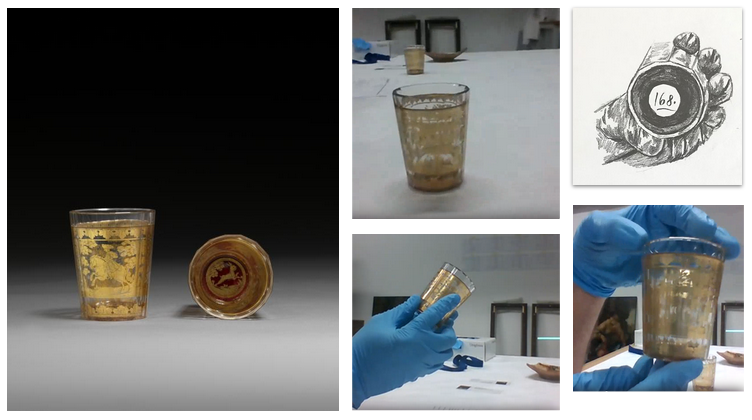

By this experiment stage, we had realised the need to introduce other elements into the sandtray. We were initially hesitant as we feared another object might take the focus away from the bear or potentially complicate the narrative we were trying to establish. When further considering what shade of blue to paint the interior, attempting to make a faithful reproduction of a box that play therapists would use. Matthew suggested that the colour blue could be referenced in the use of other objects; we could take an object such as a cave or another object resembling a lived space and paint that blue. The object appearing to suck up all of the blues we mused would be a playful nod to the use of transference in a therapy session. The finished display might straddle the need to make something life-like and conceptual.

We had also created blocks to use, a reference to the images of Margret Lowenfield working in the 1930s and decided to manipulate paper to resemble lived-in structures. These experiments did not initially appear fruitful as we realised the paper constructs looked clumsy or odd against the refined bear. The cave I had ordered also arrived late, so I could not apply the coat of blue. To further compound these feelings of disappointment, the child ( who was wise, kind and curious beyond his years) informed us that bears do not live in caves. The inner critic in me decided to stir and slither around looking for opportunity; my wise self intervened, however, and advised me that anything was possible in sand tray therapy. Why can’t the bear live in a Cave? By the end of the session, we felt no closer to deciding the final arrangement. Still, we considered expanding on the blocks, diversifying the shapes and introducing other cave-like ornaments.

Written by Danny

Third Experiment

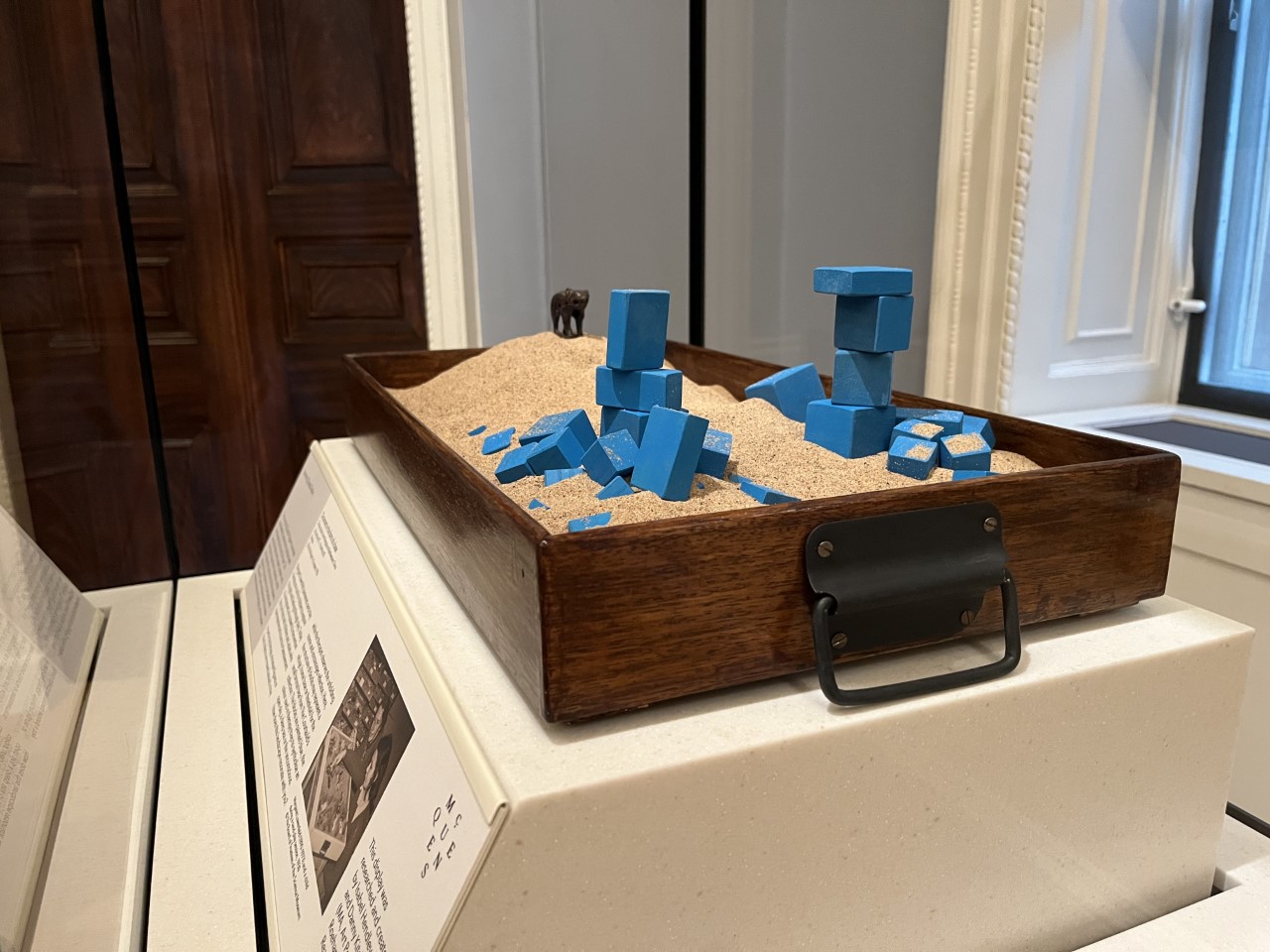

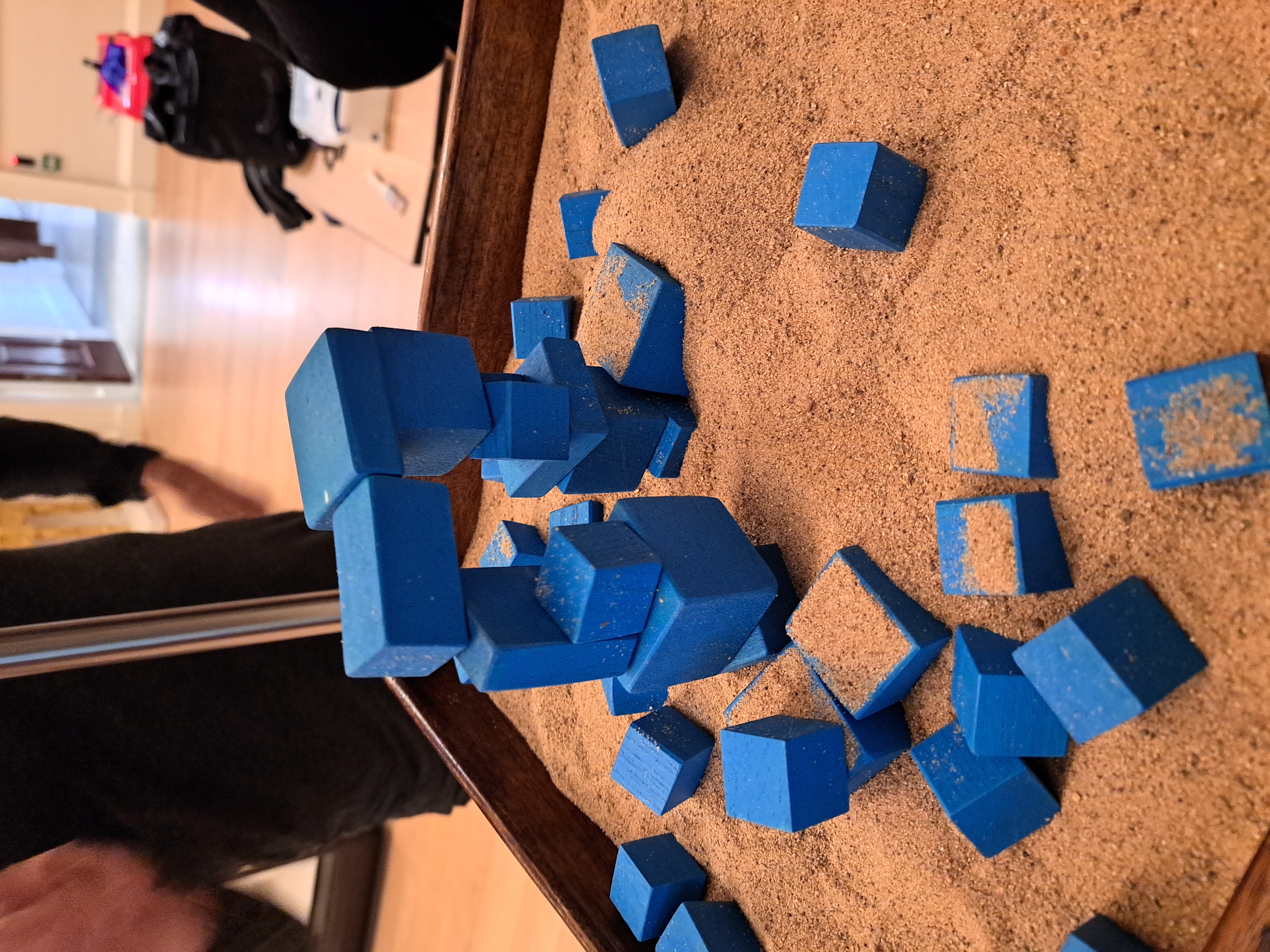

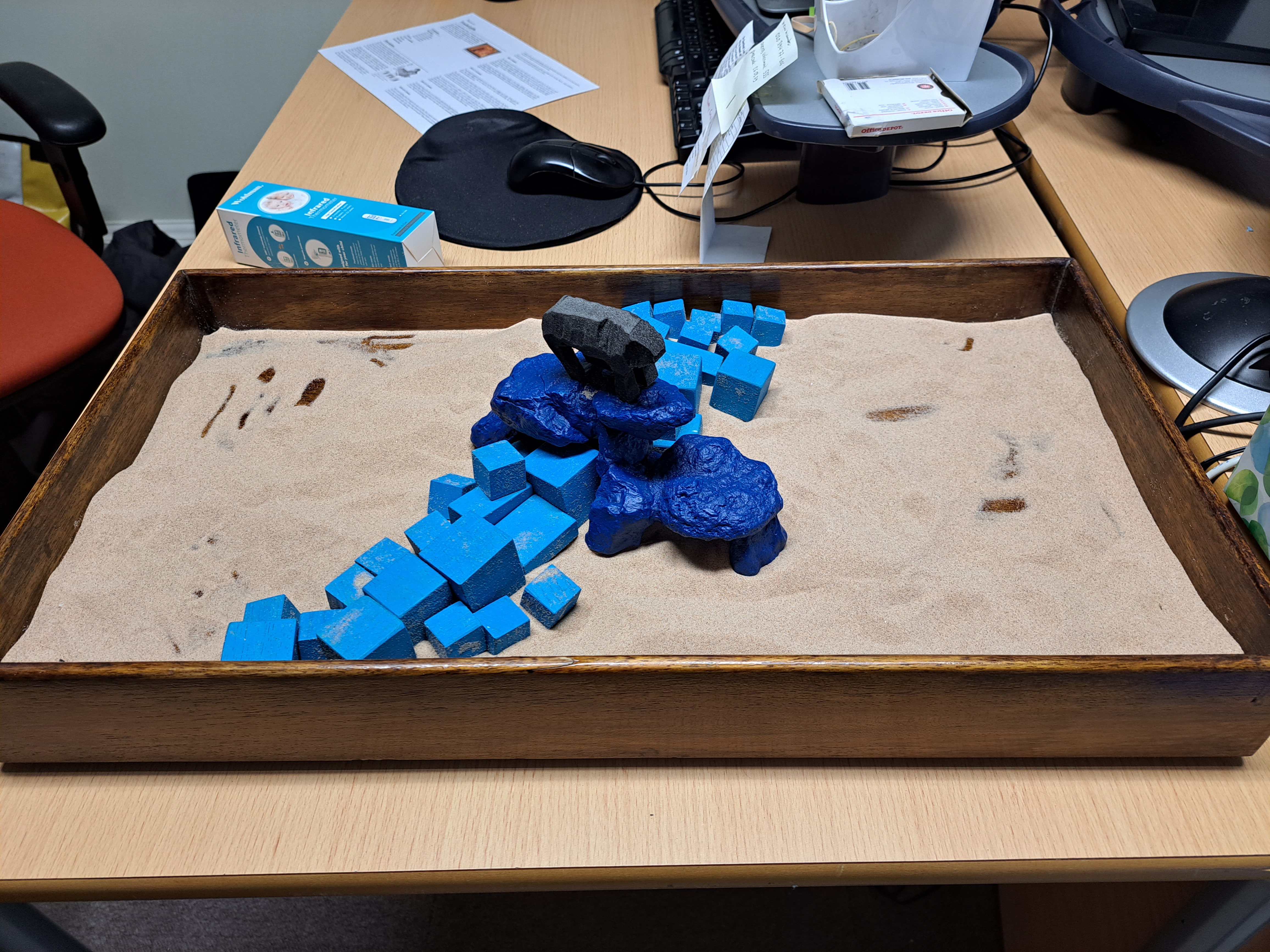

After deciding the paper was too messy, we wanted to play further with the idea of a cave or a base for the bear. It took the form of blue wooden blocks Matthew made, a plastic aquatic form Danny discovered in his local pet shop, and a more obvious plastic cave structure which could be used in sand-tray therapy sessions originally for model games. The blue blocks reminded our Courtauld colleague Martin of the educational play materials developed by Friedrich Fröbel called ‘Froebel gifts’.

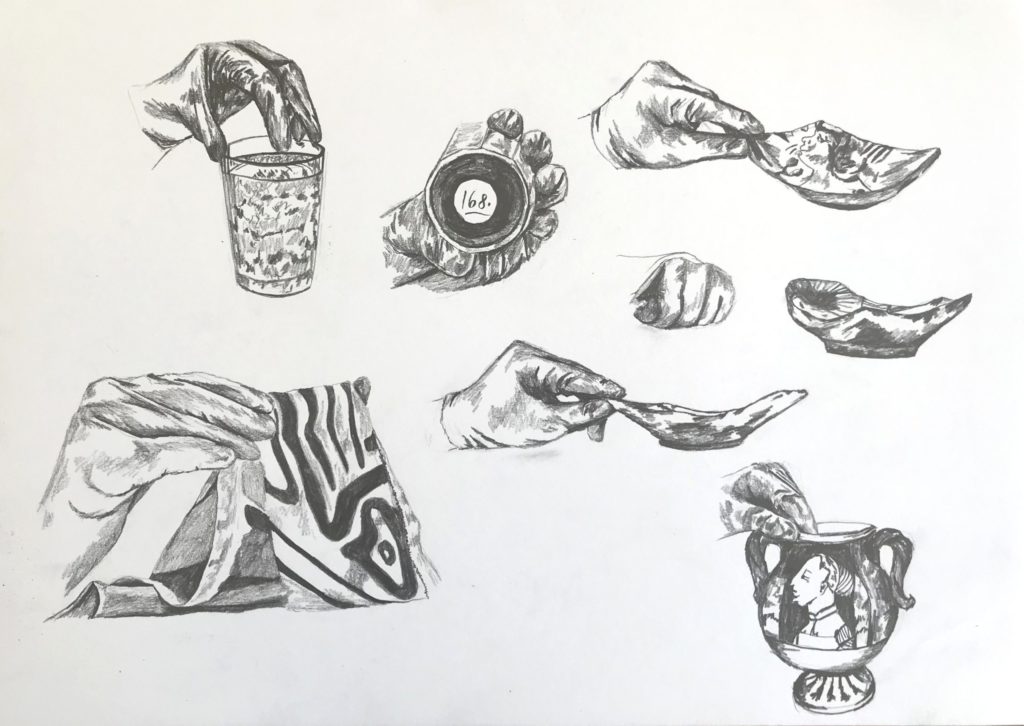

In the tray, Danny and I played with different iterations of home bases, tumbling ruins or remnants of places. We found the blocks leaning on the edges of the tray or becoming submerged in the sand intriguing. Stark forms like bridges, walls, barriers or hiding places became possible options for us. We created a circle with blocks around the bear, which reminded me of conflicts in how humans have used bears in different contexts – as symbols of strength and courage yet so often forced to perform for human entertainment and the harsh realities of the animal’s captivity. The circle figuration in the sand tray also reflected a response image Danny created if our second reflective art-making session. This experiment was generative, and I felt like we had various options for the display, reflecting our training as art therapists. We considered how leaving the final display idea open and spontaneous can reflect the true spirit of sand tray therapy. I also wondered whether wanting to keep options open was a way to hold off deciding on the display and what I felt about the experiment process and its resolution.

Written by Isabel

Final Experiment and install

As the final opportunity approached, we were distinctly aware that ‘time was running out. We had yet to decide on the final arrangement and had missed the opportunities to play due to our clinical placements taking up more space. Admin and a half-finished website were skulking around the corner. Cinematically we both arrived late to the gallery in the morning, which appeared to deprive us of precious time. If anything, this was a blessing as it meant we needed to be assertive and focused in the time spent.

Upon arrival, Sacha Gerstein, the curator of sculpture and decorative arts at The Courtauld and Matthew had created a structure that mirrored elements from our previous round of experiments but connected it to the immediate environment by recreating an archway, seen in a neighbouring painting. Keeping this in mind, we continued the experiments by moving the blocks to the middle of the tray. I started making a structure similar to what had been constructed previously, but we all realised it was too geometric and rigid. Isabel kindly took over and created a structure that appeared to incorporate the cave-like elements from our previous weeks, the archway and much more. It sat somewhere between existence and ruin, form and function, the symbolic and the actual. I added to this l by pressing blocks into the sand, attempting to submerge them and scattering grains of sand over the blocks. After some discussion and reflection, we unanimously decided that this should be the final arrangement as not only was it visually pleasing. But inhibited the notion of play and was ripe with symbolic material and opportunity. It appeared to sit well in the space naturally, and a part of me connecting with the object was curious if it had found what it was looking for.

We returned a few weeks late and installed the final display. The final arrangement of the blocks was tweaked slightly to create a bit more distance between the blocks and the bronze bear, which we all felt worked better visually.

Written by Danny