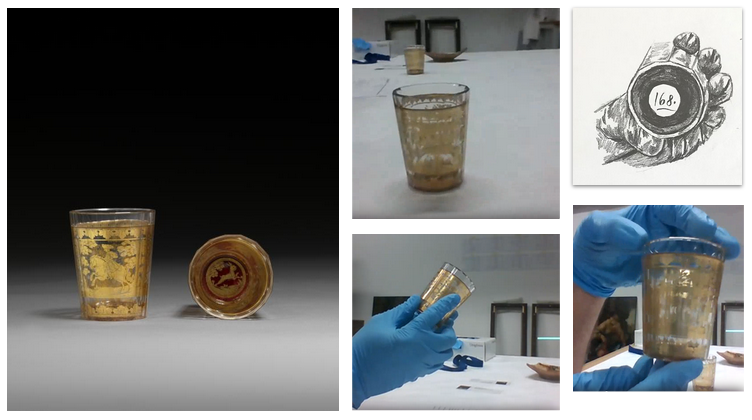

In writing this last blog post, I’m finally bringing my wonderfully long Illuminating Objects internship to a close; my second object, the pair of Zwischengoldglas beakers are now installed in The Courtauld Gallery and await the grand reopening on 19th November.

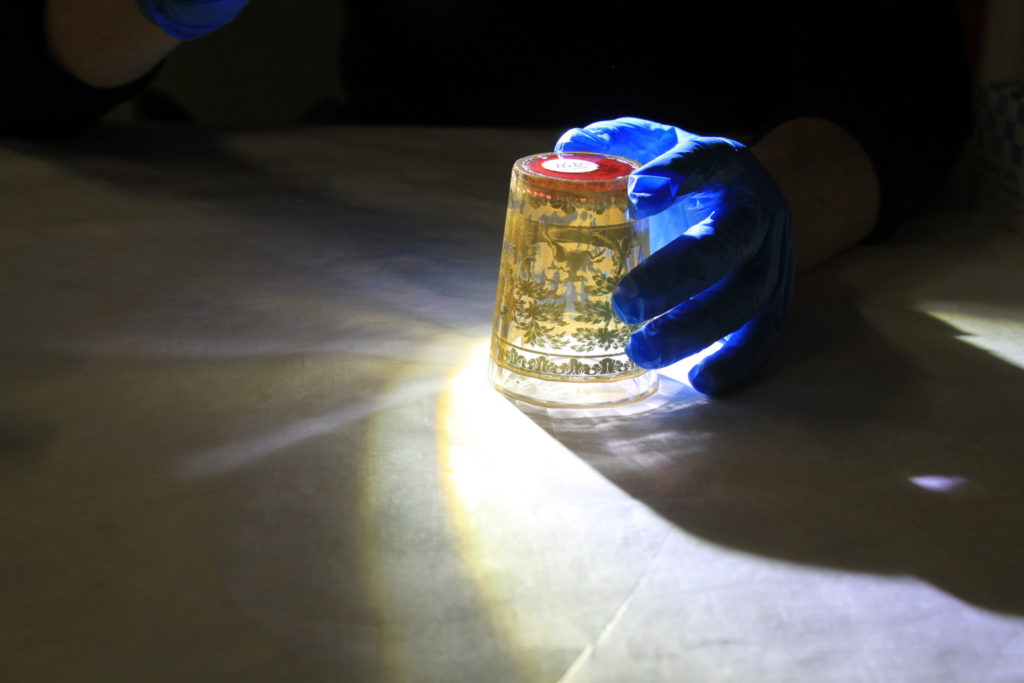

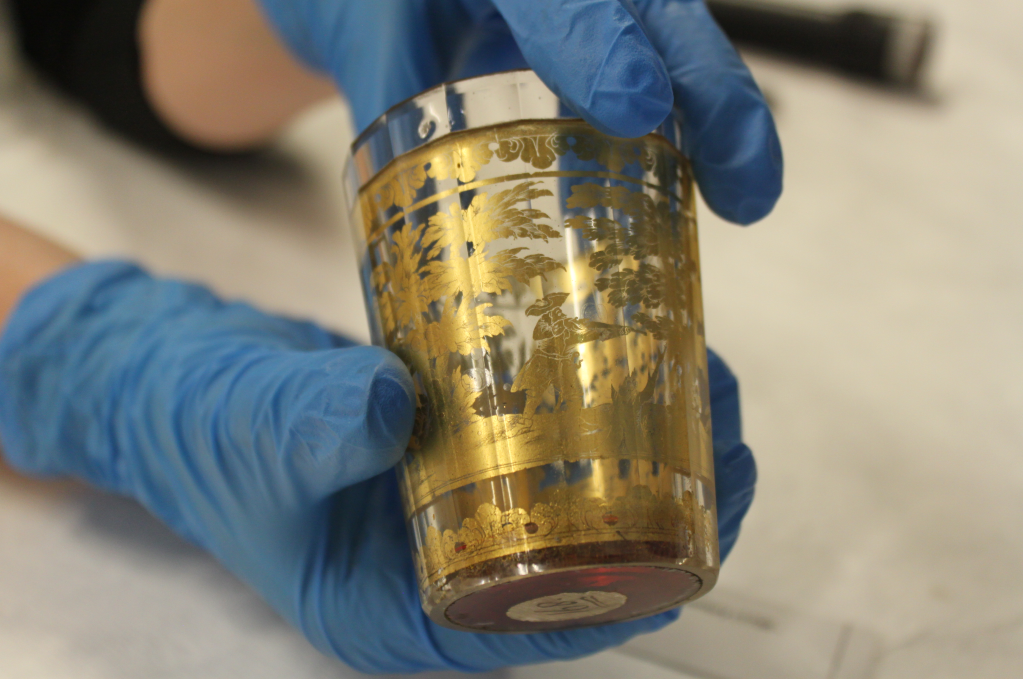

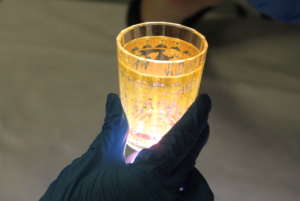

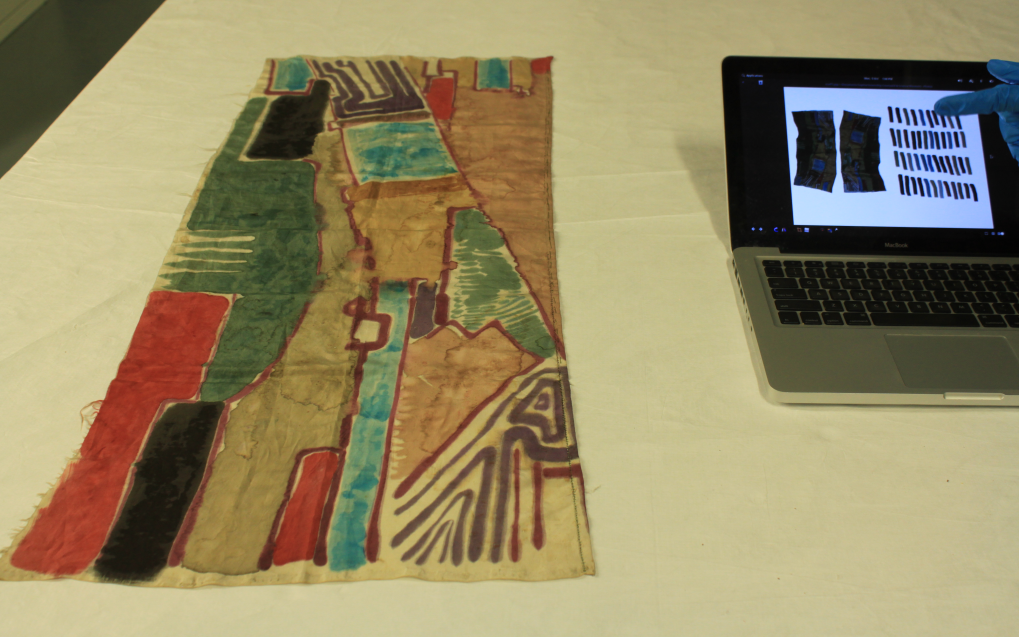

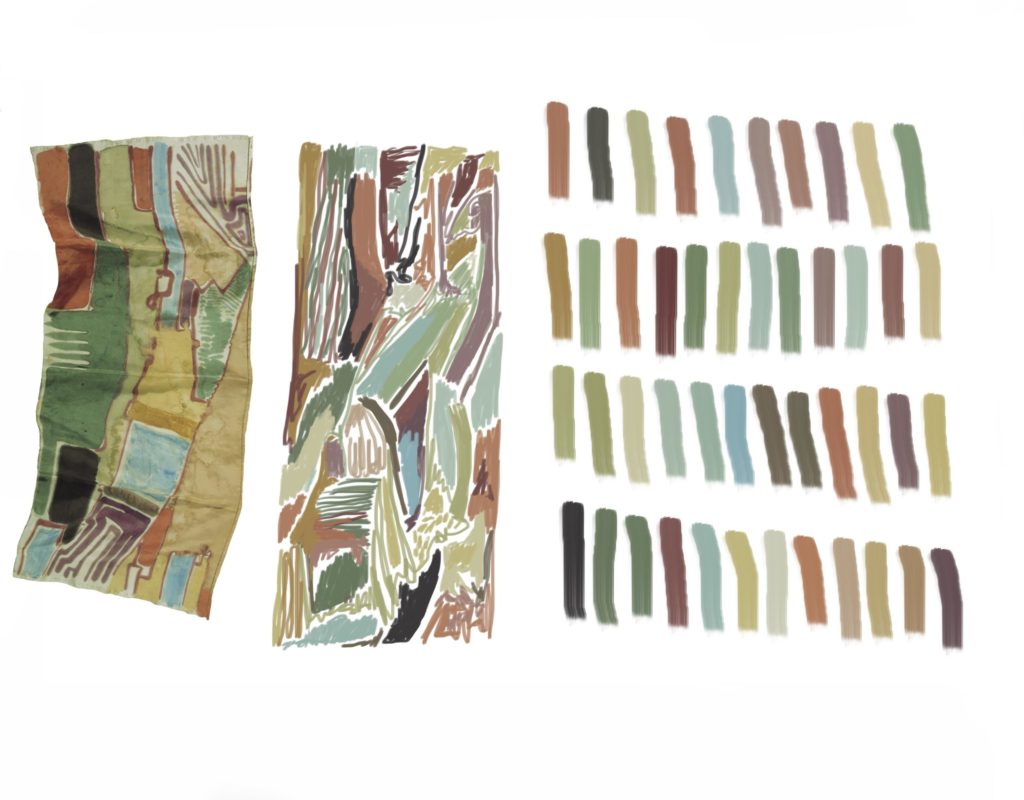

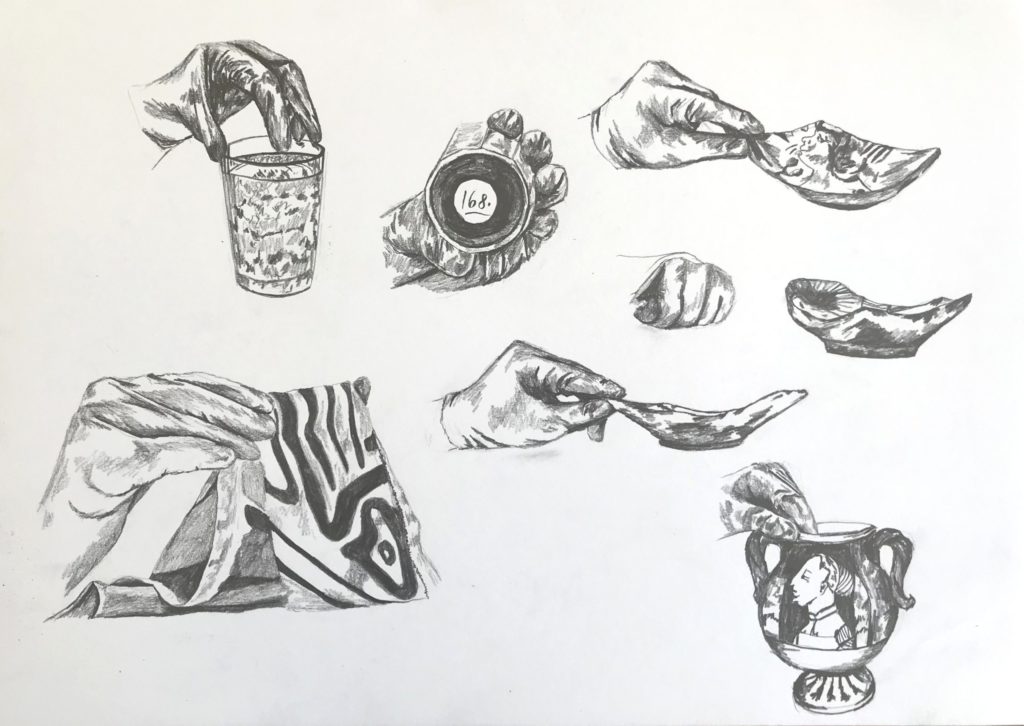

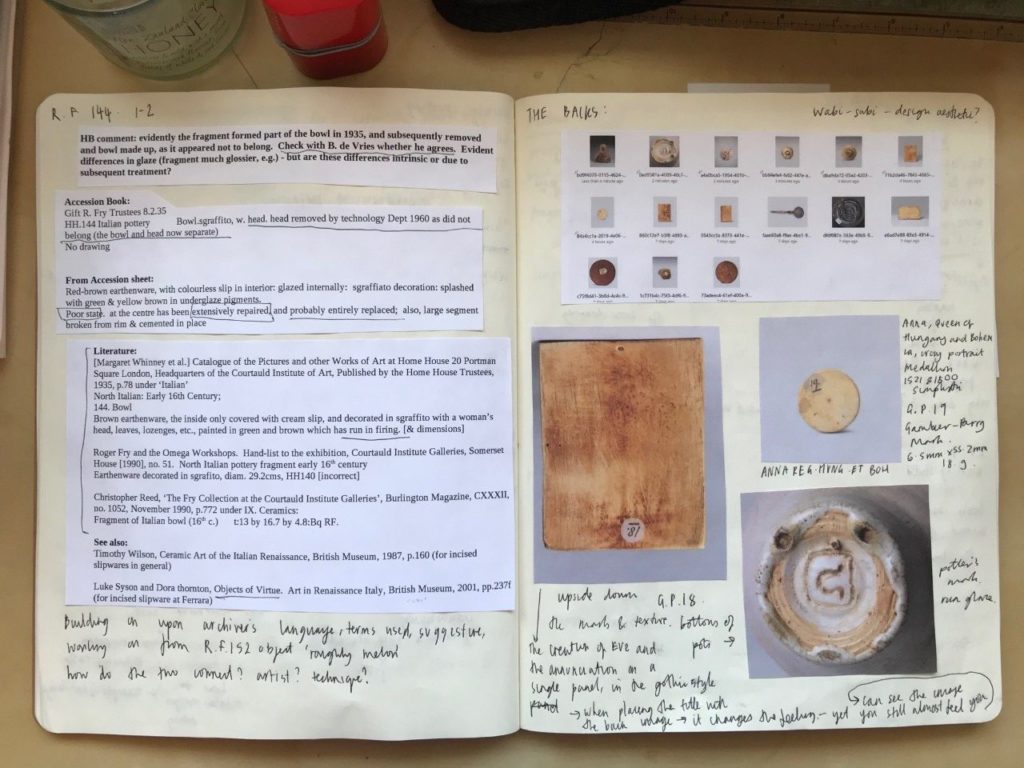

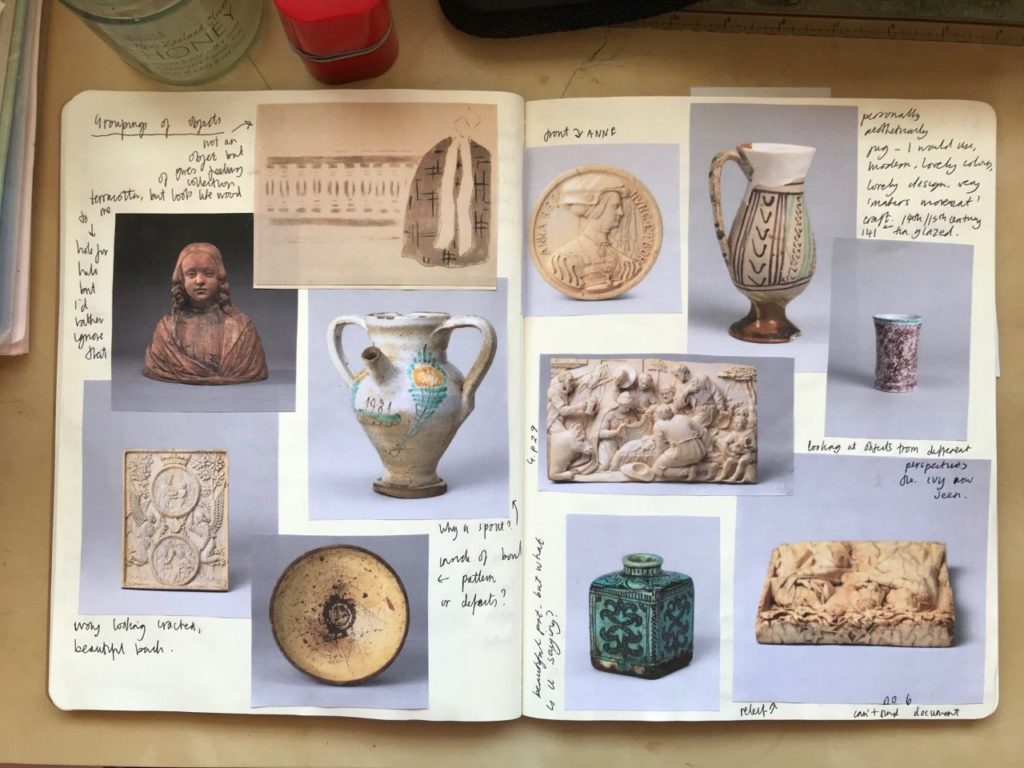

One of the main starting points for the display was thinking of my own practice in terms of my physical art space/studio/work table and thinking of the workspace as an art object, which brought subsequent discussion of a still life working environment, with tools of research and tools of fabrication. The idea of capturing something mid-process allows the visitor to have a fluid interpretation of the piece. We wanted to contextualise the era of early 18th-Century Bohemia, where the glasses are from, with a composition showing how we imagine its history in terms of an alchemist’s studio or an elite post-hunt drink. We used the objects as vehicles for story-telling and created threads to feed the visitors’ interest, whilst also emphasising the role of the accidental. This hopefully gives a little feel of what we were initially thinking with the display.

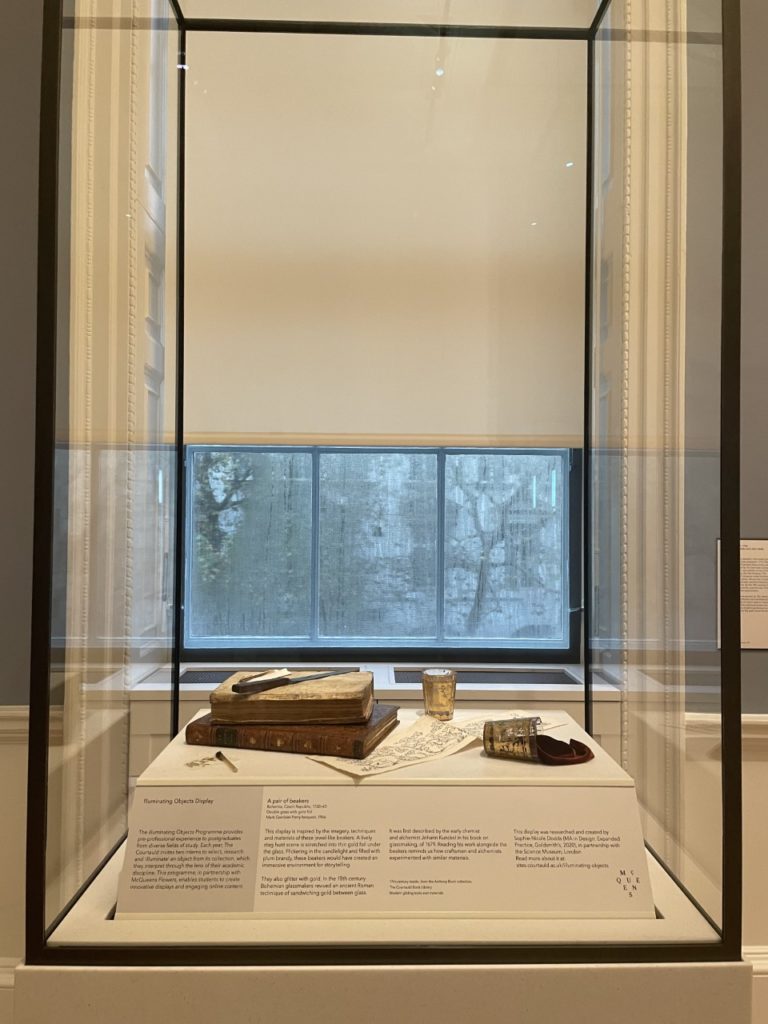

In September I met with Sacha and Matthew to install the scene of narrative objects in the 18th Century room. Their new home was to be a beautiful new case in a simple glass structure, which you could walk all the way around and view from different angles of the room, which was perfect.

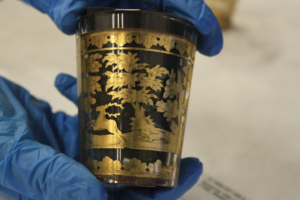

Firstly, a conservation report is done before the beakers are installed so that there is a record of exactly what condition they are in. Then another one will be done afterwards to make sure that nothing has changed. This was also where I saw for the first time the Victorian collector’s archival sticker, which had been taken off one of the glasses (and preserved as a document belonging to the object) so the smiling hare could be seen properly. The sticker had been placed onto some delicate paper and was a beautiful object in itself!

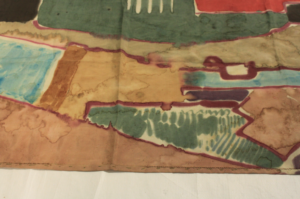

What seemed to be quite a simple process actually took slightly longer as we played around with the positioning of the objects a couple of times. I had photos ready of where to place the pieces but we found whilst in the room it was important to get every angle right depending where the viewer would be entering. For example making sure the glass could be seen well in front of the window, the hunting scene on the beakers showing the specific part we wanted at the top and not underneath, arranging the drawing, books and beaker to look natural but not block the best view, seeing the hare peeking out, no loose threads on the velvet and even how the velvet draped on the surface. There was a lot more decision-making on the install day than for the silk fragment in the Science Museum. There, the design and material of the mount had already been thoroughly modified, tested and made before the install, and, the case was against the wall, so there were fewer decisions left to be made.

We then finally settled on a change from the original scene format. Bringing the beaker on its side with the plum velvet to the front and the standing cup to the back. It was great to have one final collaborative workspace around these objects with Matthew and Sacha. It was the right decision and as we all stepped back, moved around, that was it. I couldn’t believe how good it looked finally in its place. It looked better than I expected from my photos of testing it out in the storage room with Matthew. All that is left is the label to be added to the front, which when writing also came as a new learning curve of how to add all the objects to the text tombstone!

I’m so pleased with how it all came together and particularly with this last object the creative freedom I was given and how we managed to convey that in the display whilst fitting into The Courtauld’s new gallery space. I am going to miss getting absorbed and engaged into my research and work here, the collaboration with Sacha, Matthew and Katy and just the whole eye-opening process to the world of art history and galleries. Its been a rewarding experience and I am going to take many of the new skills I learnt here into my practice of design, to hopefully design and make better.

I hope viewers are intrigued by it, move around and look from all directions to see something different each time. I look forward to seeing what people think of these beautiful beakers within this display!