After weeks of research, proofreading, soliciting the opinions of experts in West African carving, textiles and craft and meetings with the web designer, marketing team and mount maker, the project has eventually come together with the final installation of the pulley.

Gathering in the gallery early on the morning of the 4th of June with the curator, graphic designer, conservator and gallery technician the case was prepared, the labels arranged, and the mount fixed in place ready for this beautiful carved tool to go on display.

In the quiet of the gallery, in its gleaming, illuminated case and alongside Modigliani’s Female Nude of 1916 – a painting that was inspired by sketches of Ivorian carvings made at the ethnographic museum in Paris – the loom pulley was transformed.

Having handled it in the store and looked at it several times since, I felt that I already knew the object quite well. Installed in the gallery, though, it took on a completely new light.

We had been worried that, as a small object, the loom pulley might be dwarfed in the Illuminating Objects case.

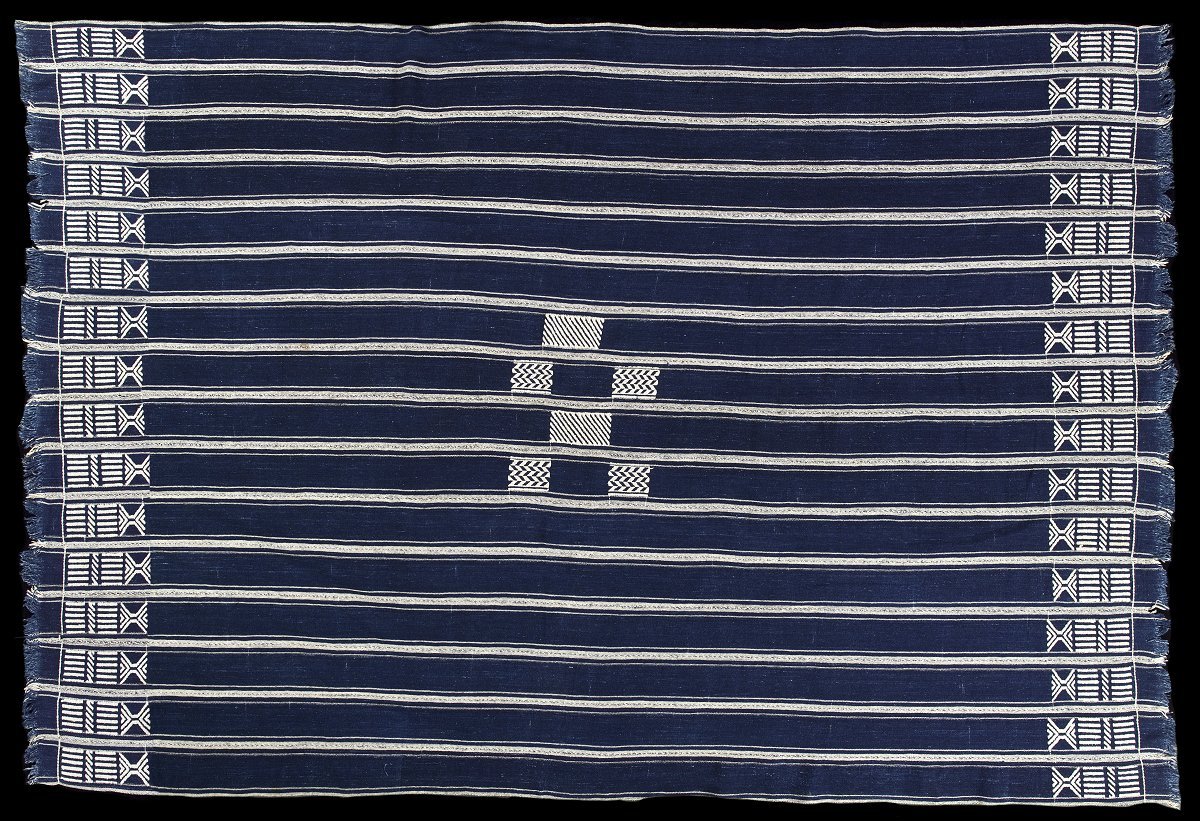

Considering that the display explores the tool as it was used by Guro weavers in their work, it was also important that its visual presentation and position in the case mirrored how a pulley would have sat in a craftsman’s loom.

Having looked at photos of a Guro loom, Colin, the mount maker, had constructed a simple and stylish solution to this problem. Looking at the pulley in its case, its presence is striking.

The delicately carved nose and downcast eyes of the woman’s face catch the light, drawing the eye across the room to the pulley and placing it alongside the elegance of Modigliani’s Female Nude.

My involvement in the project is now coming to a close and all that remains is for me to say thank you to everyone who has been involved!

I am very grateful to Dr Sacha Gerstein at The Courtauld, Prof. Trevor Marchand and Prof. Anna Contadini at SOAS, Dr Michaela Oberhofer and Eberhard Fischer at the Rietberg Museum in Zurich and Dr Duncan Clarke for all of their support and help over the past few months, and of course to my friends at the Agotime Weaving Centre in Kpetoe, Ghana, who taught me so much about weaving and what it means to be a craftsperson in West Africa.