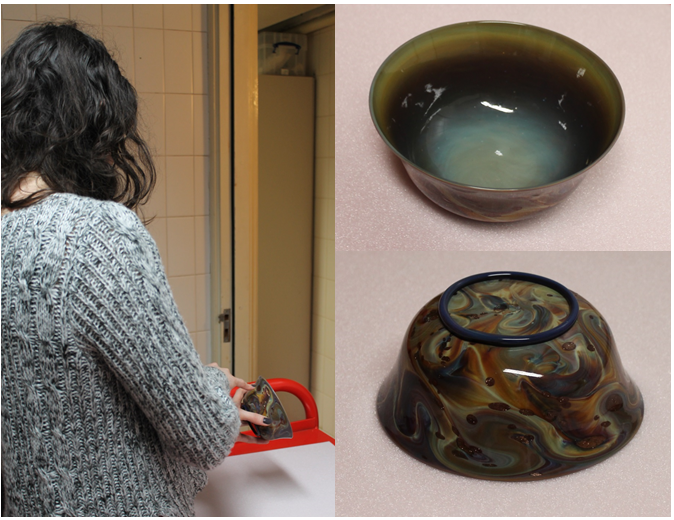

After having spent several weeks researching my Illuminating Objects glass bowl, I got the chance to see it in the flesh again for a bit of a scientific investigation. I felt quite at home visiting a lab and using a microscope, but seeing the Courtauld’s conservation labs, filled with paintings hundreds of years old, was a different experience!

After having spent several weeks researching my Illuminating Objects glass bowl, I got the chance to see it in the flesh again for a bit of a scientific investigation. I felt quite at home visiting a lab and using a microscope, but seeing the Courtauld’s conservation labs, filled with paintings hundreds of years old, was a different experience!

I had come across an article published in 1894 by a mineralogist, Henry Washington, who was a descendent of George Washington. His interest in minerals led him to Murano, in Venice, the centre of the glassmaking industry, as this was where man-made imitations of natural stones were being developed. Washington managed to procure some samples of aventurine, ‘through the kindness of Signor G. Boni of Rome’ – both a prime example and a failed attempt – for his investigations.

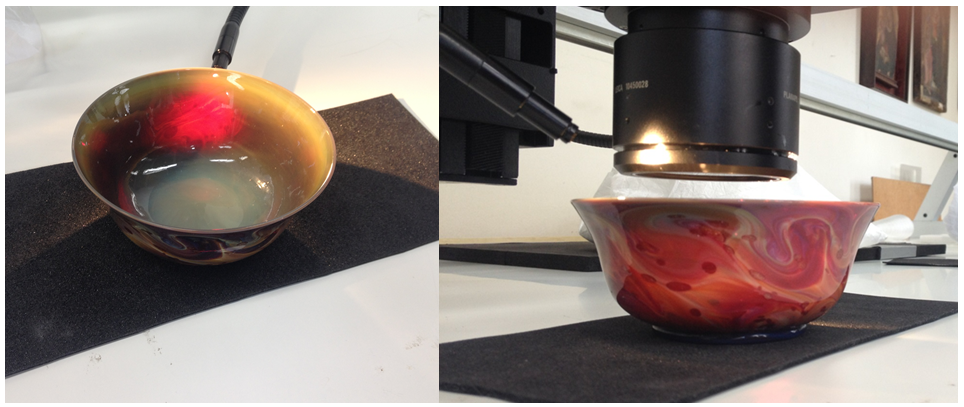

Washington says that aventurine was one of the first ever substances of a mineralogical nature (that is, its structure) to be studied under the microscope. So, 121 years after Washington peered down the microscope at a chunk of aventurine, I did the same to the aventurine samples in my bowl.

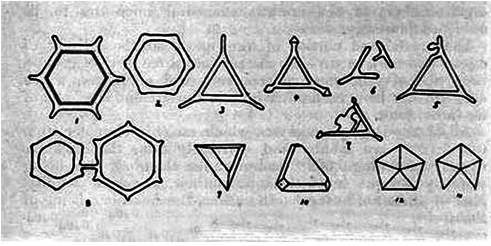

The following pictures are taken at 120x magnification:

Looking closely, you can just make out individual crystals of copper, which give the aventurine its sparkle. They form triangular and hexagonal crystals, something noted by Washington back in 1894. Unfortunately, Washington was slightly better equipped than the Courtauld in terms of his microscope’s power, and was able to see up to 200x magnification, while 120x was as close as we could get (Such high magnification is unnecessary for the work the Courtauld needs the microscope for, but is rather low for today’s capabilities).

While we were looking at the bowl under the microscope, I noticed a peculiar phenomenon of chalcedony glass. I had read once or twice in my research about a ‘red glow’ that was characteristic of chalcedony glass when a light was shone on it, but it hadn’t been described any further. Where the spotlight used to illuminate the bowl for the microscope was aimed, the glass beneath it shone red! With a bit of rearranging of the light source, we captured these amazing images of the glowing bowl.

Getting a closer view of the bowl under the microscope has really let me see the object in a new light (pun intended!). This little bowl certainly has more to it than first meets the eye, and as I approach the end of the project I am eagerly awaiting its installation in the Courtauld Gallery.

The Courtauld Gallery is one of the last places I would have guessed I would be working, if you had asked me a few years ago. At this time, a pharmaceutical or neurological laboratory would have been more in line with my expectations. But, after three years of degree study in Biomedical Science, I decided life at the lab bench wasn’t for me and I turned myself over to the humanities for a degree in Science Communication, in order to share my love for science with the public.

The Courtauld Gallery is one of the last places I would have guessed I would be working, if you had asked me a few years ago. At this time, a pharmaceutical or neurological laboratory would have been more in line with my expectations. But, after three years of degree study in Biomedical Science, I decided life at the lab bench wasn’t for me and I turned myself over to the humanities for a degree in Science Communication, in order to share my love for science with the public.