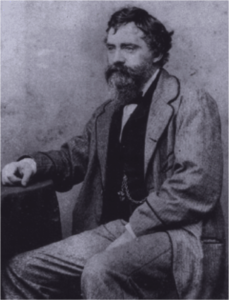

Thomas Gambier Parry (1816-1888) was a Victorian gentleman of enormous energy who used his wealth to explore the world, educate himself, and better the lives of others. He was a philanthropist, amateur artist, and author—but he is perhaps best remembered as a discerning collector who built a formidable collection of medieval and Renaissance fine and decorative art. Gambier Parry’s aesthetic sensibilities were deeply influenced by his strong religious feeling: he was a devoted Anglo-Catholic and a committed churchgoer who actively engaged in Church-related debates of his day. His collection of sacred art bears witness to a man whose love of the beautiful was deeply intertwined with his longing for the sacred.

The Life and Legacy of Thomas Gambier Parry

Gambier Parry’s family earned their wealth as directors of the East India Trading Company. Both his parents died before he was five years old, leaving him in the care of his mother’s relatives. Gambier Parry was educated at Eton and Cambridge, and in 1838, he purchased Highnam Court, an estate in Gloucestershire, where he lived for the rest of his life. But Gambier Parry was no idle country gentleman. He travelled extensively across Europe, both with his first wife Isabella, who died in 1848, and later with his second wife, Ethelinda, building an impressive collection of art, and refining his aesthetic sensibilities.

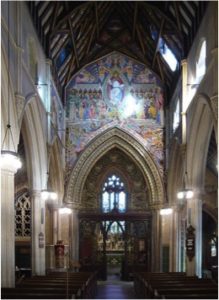

In 1851, Gambier Parry commissioned his friend, the High Church architect Henry Woodyer, to build a lavish church on his estate. He decorated the interior himself using an original painting technique he called “Spirit Fresco.” He later published both a manual on this method, as well as a treatise on his aesthetic views. In addition to these artistic pursuits, Gambier Parry devoted himself to philanthropy, founding and funding an orphanage, a school, and a children’s hospital. After suffering a fatal heart attack, he was buried at Highnam Church. He was succeeded by six children, the youngest of whom was the notable composer, Sir Hubert Parry.

“We Anglo-Catholics”: Gambier Parry & the Victorian Church

One of the most significant religious developments in Victorian Britain was the rise of Anglo-Catholicism, a movement among High Church Anglicans that sought to reconnect the English Church with its traditional roots. Anglo-Catholicism emerged in the 1830s and spread rapidly, particularly in well-educated circles of the Church of England. With renewed interest in ecclesial tradition, High Church Anglicans eventually began to revive ornate liturgical practices that had been abandoned during the Reformation. This paved the way for the development of materially rich forms of worship within Anglicanism. The beauty and ritual of the movement greatly appealed to Gambier Parry, who was a committed Anglo-Catholic. However, he had little interest in the study of doctrine, and his faith was emotional rather than intellectual. Gambier Parry’s idealism is captured in a journal entry of 1852, in which he describes religion as, “simple expression of feeling… undisturbed by the mere outward appearances of actual historical fact.”

Gambier Parry & Ecclesiology

Gambier Parry’s religious sensibilities aligned with Ecclesiology, a movement in High Church Anglicanism that promoted the restoration of English churches according to Gothic architectural principles. He was an active member of its leading association (the Cambridge Camden Society, later renamed the Ecclesiological Society) throughout most of his life. Like many members of the Society, his faith was fueled by his passion for architecture, and in his journals, he often reflected upon the spiritual power of churches he visited while travelling. For example, in May 1851, he described the Cathedral in Milan as an emblem of the ideal of Christian hospitality: “…stretching its arms north, south, east and west, it calls all the neighbouring Christians to meet together beneath its wide spread roof, and offers to them… an emblem of unity and peace.”

Holy Innocents: Gambier Parry’s Legacy of Faith

Gambier Parry’s religious idealism is perhaps best memorialized in the church he commissioned to be built on his estate at Highnam, which he considered to be his greatest legacy. Holy Innocents was designed according to Ecclesiological principles and extravagantly decorated with colourful frescos and stained glass windows. The church is a testimony to a man whose devotion to God was closely intertwined to his love for architecture. Following the consecration of Holy Innocents in 1851, Gambier Parry wrote in his journal, “Whatever is good is God’s doing. It is an awful privilege to be even ever so mean an instrument for good in His hands.”

The Ministry of Art: Thomas Gambier Parry on Devotion Through the Arts

Gambier Parry’s publication on his aesthetic views – titled The Ministry of Fine Art to the Happiness of Life – provides some insight into his understanding of the relationship between art and faith. While the essays provide an interesting glimpse into the mind of a nineteenth century aesthete, Gambier Parry’s efforts produced neither an original, rigorous argument, nor a masterpiece of Victorian prose (the tone of his treatise is highly florid). However, the work does reveal his belief that beauty provides a bridge from this world to the next, and that art both educates us about, and connects us to, the Divine.

Beauty & Idealism

“The purpose of the Fine Arts is the expression of beauty,” Gambier Parry asserts at the outset of his treatise. In his view, beauty found in the world around us is always, “the symbol of that Divine light which illuminates both [nature] and [men].” Gambier Parry ascribed to an idealist understanding of beauty: he believed that material forms of beauty are inferior the expression of the immaterial, inscrutable beauty of God. Beauty, he writes: “speaks, calls, appeals to him from and for a higher life than that of sense…”

“Art is the Chorus of Universal Praise”

Throughout The Ministry of Fine Art, Gambier Parry expresses his conviction that art aids contemplation and enriches our spiritual life. In his chapter on sacred architecture, he proclaims, “Art is the chorus of universal praise,” and explains his belief that art and architecture can vitalize worship. And elsewhere, Gambier Parry writes that religious art is, “…an aid to the weak, a delight to the strong, a store unfailing for art to use, to adorn not walls alone but minds, with thoughts of what is highest, noblest, loveliest, that the blessed God had spread along the path of life, to lead them upward to Himself.” Here again, we can see his idealism: art leads us up from our path in this life toward what is “highest, noblest, [and] loveliest”—in essence, toward God.

The Book-Shaped Pendant in Thomas Gambier Parry’s Collection

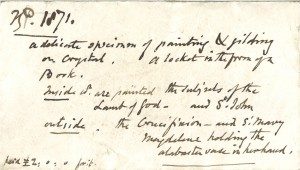

It would appear that Gambier Parry most likely acquired his pendant in 1871.

He scrawled this date on the back of an envelope along with the following description:

A delicate specimen of painting & gilding on crystal. A locket in the form of a Book.

Inside it are painted the subjects of the Lamb of God – and St John

Outside the crucifixion, and Mary Magdalene holding the alabaster vase in her hand.

Paid £2.00 for it

Was there a devotional reason for his interest in the pendant? It is quite unlikely that he would have worn it, but would he have kept this object somewhere personal like a bedside table, or hung it in a chapel? While we cannot answer these questions with certainty, we can surmise a few possible reasons why the collector felt drawn to this beautiful pendant.

Gambier Parry on the Art of Glass Painting

Gambier Parry devotes an entire chapter his book, The Ministry of Fine Arts to the Happiness of Life, to the subject of stained glass art. He felt that painting on glass was a difficult and noble artistic endeavor, “…with its own laws, its own powers, its own limits; …it is light that has to be dealt with, not shadow; translucent glass, not solid canvas; open air, not a picture-frame…” Could the glass panels have reminded him of the stained-glass windows that he so admired in the great Gothic Cathedrals of Europe?

A Protestant-Catholic Fusion

Gambier Parry may have been drawn to this object for its unique book shape. He was a well-educated man with an insatiable thirst for knowledge, and the book may have inspired him. But the book also suggests more than this: the Bible is a symbol of the ideals of the Protestant Reformation, when the Scriptures were translated into vernacular and made available to all. Yet the iconographic decoration of this book resonates with a Counter-Reformation appreciation for art and beauty. We might say that the pendant fuses Protestant ideals and Catholic aesthetics, which would have suggested a meaningful emblem for the Anglo-Catholic collector’s own religious identity.

Back to A 17th Century Pendant