The trial of Oscar Wilde in 1895 led to, as historians have argued, a conceptualisation and increased awareness of homosexuality. Within previous centuries the biblical notion of ‘sodomy’ fuelled the belief that all sexuality was fluid and that every man was capable of committing the heinous crime of same-sex relations. As a result of the Wilde trials however, the newly defined legal and medical idea of the ‘homosexual’ allowed for sexual orientation to become a marker of identity. It is no surprise, therefore, that this new label of social categorisation infiltrated ways of dressing and enabled the notion of homosexual style to emerge.

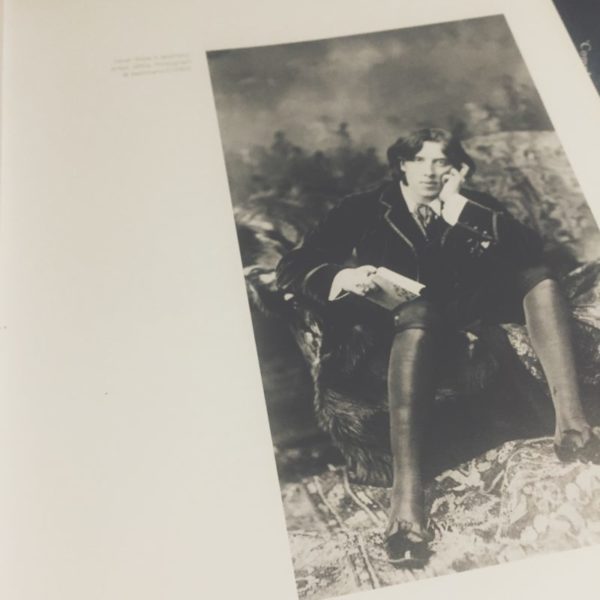

Within the exhibition catalogue, Queer Style, Valerie Steele locates the inception of homosexual dress within the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries in her discussion of Oscar Wilde. Wilde is often associated with two differing styles of masculine dress that are oft associated with the figure of the homosexual male: the ‘aesthete’ and the ‘dandy’. Steele defines the ‘aesthete’ as a flamboyantly dressed male whose outlandish sense of style became a marker of sexual deviance. For Wilde, his signature green carnation was adopted as a fashionable statement of such deviance amongst aesthetes.

While aesthetic modes of dress acted as a more visible form of locating the homosexual, dandyism revealed the sexual non-conformity of the individual through the hyper-conformity to male fashions. Steele observes how the dandy adhered to the male sartorial code to such an extent that he distinguished himself from his peers. When Wilde later transitioned to a dandyist approach to dress, he was thus able to signal his ‘deviance’ through conventional fashions. The dandy could protect himself within a heteronormative and homophobic society while also using his hyper-conformity as a means to present his homosexuality to those keen enough to observe it.

Wilde was a key figure in not only raising awareness of homosexual identity, but also in showing how this newly defined identity could be explored through dress. The impact of Wilde’s trial can be felt even now, as you see queer and homosexual aesthetics continually evolving and being redefined. Ultimately, the tragic downfall of Oscar Wilde allowed for the figure of the homosexual to be made visible within a heteronormative society, and it is this visibility that enabled the very notion of queer style to emerge.