During last week’s study trips, we were lucky enough to snoop around Hampton Court Palace’s Royal Ceremonial Dress Collection. Items within their collection of 10,000 objects date from the late sixteenth century to the present day. They range from Queen Victoria’s monogrammed underwear to That Dress worn by Princess Diana when she danced with John Travolta at a White House dinner in 1985. All of Hampton Court’s archive storerooms are located in converted palace apartments and, rather fittingly, the dress collection is housed in an old laundry room. Curator Matthew Storey kindly showed us some highlights of the collection which sat neatly within the 1920-1960 timeframe of the Documenting Fashion course. From ambiguously-shaped white garment bags suspended ghoulishly from rails, he revealed two examples of menswear with royal significance.

The first was a tweed suit belonging to the Duke of Windsor, previously titled the Prince of Wales and later King Edward VIII before his abdication in 1936 in order to marry American divorcée Wallis Simpson. Made by Savile Row tailor Fredrick Scholte in 1932, the jacket embodies the Duke’s philosophy of ‘dressing soft’. Prioritising comfort and movement, the Duke severed ties with social rituals of dress and became an icon of men’s style in Europe and America. His sense of ease helped loosen the stiff grip of conformity in relation to men’s tailoring. Most noticeable about the garment itself was its own movement. As it was handled delicately by gloved hands, the double-breasted jacket billowed of its own accord with an unusual fluidity for such stiff tweed. The movement of the garment itself catered to the dynamism of the wearer. Scholte’s expert tailoring, known as the English drape or London cut, included more material across the chest and back, enabling this ease of movement as well as creating a broad, masculine silhouette. In his own words, the Duke praised Scholte’s ‘rigid standards concerning the perfect balance of proportions between shoulders and waist in the cut of a coat to clothe the masculine torso’.

In this image, the Duke manages to look suave whilst posing with bunches of asparagus. Pipe clasped between teeth, he stands with one leg raised. The double-breasted cut, broad lapels, sloping shoulders and buttons on the cuffs are all similar, if not the same, to the tweed jacket held within the Royal Ceremonial Dress Collection (it’s surprisingly difficult to identify patterns of tweed by squinting at black and white heavily pixelated reproductions of houndstooth without inducing a hefty migraine). Despite pulling across his abdomen, the jacket holds its shape over his chest and shoulders, maintaining its neat, square silhouette. Curator Matthew Storey explained the difficulty of finding a mannequin to best display this garment, looking for images of the Duke in swimwear to get an understanding of the body held within the garment. Under the broadening silhouette of Scholte’s construction, the Duke’s frame is almost surprisingly slender but still athletic. Usually mannequins are built to fill a garment and offer bodily support. However, with Scholte’s English drape, the jacket is designed to hold its shape with minimum support even on a humble hanger.

© Kerry Taylor / BNPS

The matching trousers, made by Forster and Sons, are also cut in a quintessentially English way; they are high-waisted to elongate the leg, with loops for braces to be attached. They also feature a zip fly, a fairly recent innovation, instead of buttons, which further adds to the idea of ease and practicality promoted through the Duke’s clothing. His clothing was customised, such as the left pocket of his trousers being bigger to accommodate his cigarette case. However, the Duke stated ‘I disliked the cut of [English trousers]; they were made…to be worn with braces high above the waist. So preferring as I did to wear a belt rather than braces with trousers, in the American style, I invariably had them made by another tailor’. Following his abdication, his style was progressively Americanised as he severed ties with his regal roots. The Duke sent his fabric to H. Harris in New York, to be tailored in the low-waisted American style. The Duke ‘gave [H. Harris] a pair of my old London trousers, and he copied them admirably. Since then, I have had my trousers made in New York and my jackets in London, an international compromise which the Duchess aptly describes as “pants across the pond”.’

In 1924, Men’s Wear magazine stated ‘the average young man in America is more interested in the clothes of the Prince of Wales than in any other individual on earth’, revealing the global impact he had on the relaxation of men’s fashion. In his autobiography A Family Album, the Duke articulated that ‘I was in fact “produced” as a leader of fashion, with the clothiers as my showmen and the world as my audience. The middle-man in this process was the photographer, employed not only by the press but by the trade, whose task it was to photograph me on every possible occasion, public or private, with an especial eye for what I happened to be wearing.’ The Duke expressed how fashion is an ongoing, collaborative process and an ever-advancing expression of self-image.

In total contrast to the Duke’s understated yet trail-blazing style, court dress, worn in the presence of a royal, remained stubbornly rooted in the past. It exists outside trends and time itself. From the collection, we were also shown a court coat worn to the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II in 1953. The rank and status of the wearer is communicated through the sheer splendour of the silver and gold gilt embroidery, adding a symbolic and literal weight to the garment. The embroidery stretches proudly across the chest, evoking the gold braiding that adorns military uniforms. In 1820, King George IV lessened the strict regulation of court dress, meaning that garments resembling military uniforms usurped men’s colourful court coats. Instead of evolving with the times, these garments remained cemented in the past, due to tradition and ceremony that are intrinsically woven into the formality of court dress. On first inspection, a court coat from 1885 created by Henry Poole & Sons on Savile Row for Lord Boston is almost identical to the 1953 garment in the opulence of its decoration (the triangular embroidery around the collar is slightly different).

© Historic Royal Palaces / Robin Forster / Bridgeman Images

This demonstrates that court dress exists outside of the magnetic field of fashion and resists the thrust towards modernity. In contemporary civilian dress, any peacocky ornamentation was regarded as subversive to traditional notions of masculinity. In 1930, C. Flügel’s The Psychology of Clothes explored the notion of ‘the great masculine renunciation’ of elaborate elegance. For men, fashion was inherently feminine, and to be too invested in your clothing was to deny your own masculinity. Yet the court coat is separate from this. It seems to embody male vanity, neatly interweaving tradition, militant male aggression, and the feminine flair of decorative embroidery.

© Bowstir Ltd 2018

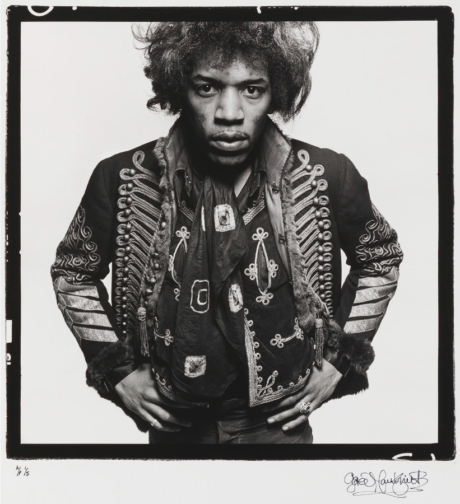

The masculine rejection of trivial fashion remained firmly in place until the 1960s, when androgyny and experimentation became the new mode. Almost ironically, youth subculture groups appropriated archaic military dress as a means of breaking away from traditional masculinity. The Portobello Road store I Was Lord Kitchener’s Valet sold on army surplus as well as vintage military jackets throughout the 1960s. Rockstars, such as Jimi Hendrix, flaunted their military gear, to protest against the Vietnam War or to sever themselves from the dull mundanity of conventional drab-toned suits. Or, like the court coat, perhaps military jackets served the purpose of self-promotion and performative male fortitude.

By Claudia Stanley

Sources:

J. C. Flügel, ‘The Psychology of Clothes’, in The Rise in Fashion: A Reader, ed. Daniel Leonhard Purdy (Minneapolis, 2004)

Maria Costantino, Men’s Fashion in the Twentieth Century: from frock coats to intelligent fibres (London, 1997)

The Duke of Windsor, A Family Album (London, 1960)