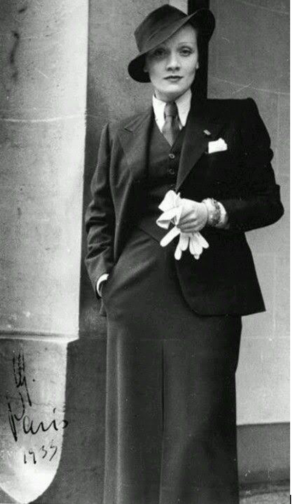

1930s fashion has always appealed to me. Whether the beautiful flowing drapery of Madeleine Vionnet or the sharp suits worn by Marlene Dietrich, much of the fashion of the decade developed the freedom in dress that we come to appreciate now – both in terms of gender fluid dress, and comfort.

The art deco movement was a key influence on fashion of the time, encouraging a celebration of technological developments and an optimism for the future in its luxurious style. Here and now, as we emerge from the covid-19 pandemic with a sense of relief, but a variety of sources for future anxieties ever-present, it is time for a reinvigoration of that same hope in human ingenuity, celebration of technological developments and optimism for the future. We need comfort, strength and vibrancy, and I think we should be looking to 1930s fashion for inspiration.

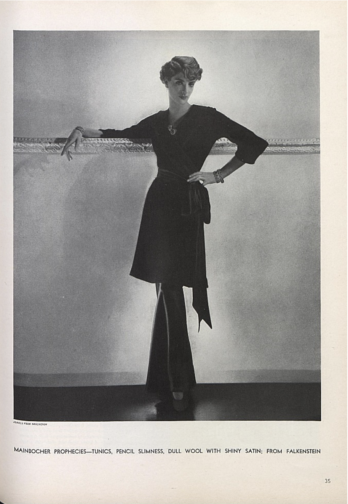

A range of comfortable ensembles are documented in the early 1930s. Anna May Wong wears an elegant, loosely fitted dress and leans against a doorway to convey her relaxed manner. Similarly, the model of Falkenstein in the August 1934 issue of Vogue leans against the wall. A rare appearance of trousers in early 1930s Vogue, the image shows a woman comfortable yet glamourous, wearing a tunic which resembles very stylish and eveningwear appropriate dressing-gown.

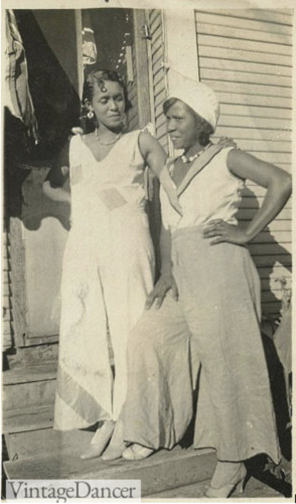

Moving from comfortable formalwear to comfortable daywear, the beach pyjamas worn by Geeshie Wiley and L. V. ‘Slack’ Thomas are outfits not only that would still be incredible on any beach, but likely will be reflected by many at the Courtauld’s graduation ceremony this summer. Wide-legged trousers and a fitted waist have been in style already for the past few years, but I’d like to see the style with more bright colours and comfortable cotton fabrics.

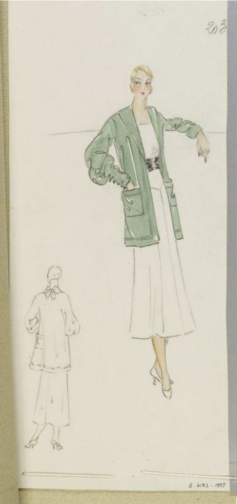

And what should we wear when there is work to be done? An oversized cardigan with deep pockets in a stunning sage green, of course. An increase in sportswear and ready-to-wear in the 1930s led to a much higher interest in collegiate fashions, such as the varsity jacket and cardigans. The flip side of increased ready-to-wear was a rise in cheaper, lower quality garments. Today, with fast fashion booming and brands like Shein churning out an endless array of garments, it is more important than ever to find clothing that we love and will wear for many years, rather than single use pieces so cheaply made that they will inevitably end up on landfill. Clothing that can be styled in multiple ways, worn in many contexts and brings us joy is vital to us having a more sustainable relationship with our wardrobe. A deep pocketed cardigan perfectly fits the bill for me.

Uncertainty and anxiety have prevailed in recent years. As we move past what has been a difficult period for many, it seems only right that we do so feeling empowered and true to ourselves. Whether or not this means buying your own power suit – you decide. But Marlene Dietrich provides inspiration not only in her incredible suit-wearing, but also in her certainty that what she wanted to wear, what she felt good in, was for her to decide. For all my advocation of a need to revive 1930s fashion, I would like to conclude by moving away from the styles that dominated that period, and rather draw attention to the underlying themes of self-assurance, comfort, and joy. It is these that we should carry with us and cultivate through our wardrobe.

By Megan Stevenson

Bibliography

Arnold, Rebecca. The American Look: Fashion, Sportswear and the Image of Women in 1930s and 1940s America (2009, London)

Wilson, Elizabeth. Adorned in Dream: Fashion and Modernity (2003, London)

https://www.reddit.com/r/costumeporn/comments/k5blr1/marlene_dietrich_in_paris_1933/

https://www.vam.ac.uk/articles/art-deco-fashion

https://vintagedancer.com/1930s/1930s-black-fashion-african-american-clothing-photos/

https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O532676/%C3%A9t%C3%A9-1933-fashion-design-madeleine-wallis/

https://www.anothermag.com/fashion-beauty/gallery/9950/night-and-day-1930s-fashion-and-photographs/10