How did your academic and professional background lead to your current role at the PMA?

Originally I was interested in the history of late nineteenth-century furniture and I attended the Museum Studies program at the University of Manchester. Everyone in my class seemed to be doing ceramics or furniture, so I thought that if I was going to find a job, I needed to choose another area to focus on. I then wrote my thesis on aesthetic dress. What I liked about the history of dress was that it combined art history, fashion history, social history, and economic history – it synthesised a lot of my interests.

My first job was at the Harris Museum and Art Gallery where I was hired as the Assistant Keeper of Decorative Arts, and I was to be in charge of activating their costume collection which had been in storage for years. My first day on the job I arrived and discovered that there had been a flood in the storage area and the entire collection was laid out in the painting gallery on tables sopping wet. I was completely thrown by that because, even though we had discussions and workshops on conservation at Manchester, I wasn’t prepared for dealing with a real conservation emergency. That sent me to thinking that I really needed to add conservation to my background.

I was there for a few years and then went to the Courtauld to study textile conservation. It was at the time when Stella Mary Newton was still teaching, and the program was split between history of dress and textile conservation. After I completed that program, I had to find a job, and I wrote to probably twenty museums in the United States and heard from two. One was Williamsburg, which was offering a curatorial position and the other was the Brooklyn Museum, which was offering conservation. I thought that since I just spent all this money studying conservation that I should at least try it, so I chose Brooklyn and was there for a few years. I then took a job at the Museum of London where I started out as a textile conservator and then switched over to curatorial.

From the Museum of London, I took a job at a private conservation centre in Chicago, but, probably the first week I was there, I knew I had made a mistake and spent the next couple of years trying to figure out how to extricate myself. I was offered a freelance job at the Museum of Fine Arts Houston and organised a small show on French fashion for them. I did this without the person I was working for knowing what I was doing. At the same time I was interviewing for a position at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. So I used to fly down to Texas, via Philadelphia and then back to Chicago. Eventually I was offered the job in Philadelphia, which had been vacant for seven or eight years. It turned out that they had to raise the money, but the Director in Houston kept on putting pressure on them to make a decision. That’s how I ended up in Philadelphia.

What interests you most about working with dress?

I’m interested in all aspects of the object – the history of its manufacture, the wearers, the materials, etc. I like that it can be viewed in many different contexts – fashion history, art history, social history and sociology, technology, and anthropology. It’s a jumping off point for exploring so many other areas.

What current projects are you working on at the museum?

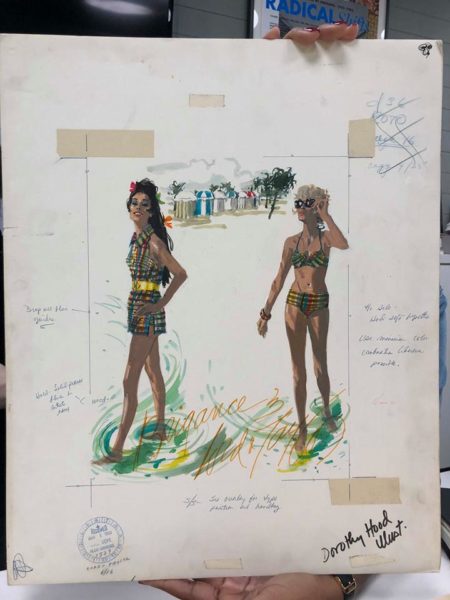

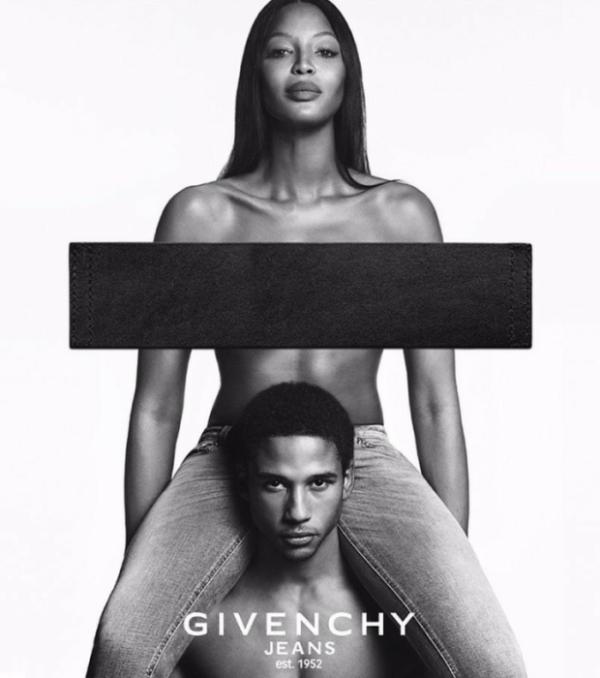

Right now I’m working on a Patrick Kelly exhibition, which will be opening on April 26, and then I have a number of other possible projects which I can’t divulge at the moment, but some are quite exciting.

What is your favourite piece in the collection?

Whatever I acquire becomes my favourite piece! As for things in the past in terms of costume, I still love Schiaparelli’s harlequin coat for the way it’s designed – the progression of the colour. But I find anything can become a favourite once you delve into it and learn about it.

How did your Courtauld degree benefit you in your career?

I received a diploma in conservation from the Courtauld. I think it has made me a well-rounded curator and has given me another perspective. The one thing that conservation did do – and I think other colleagues who have been conservators and then become curators agree with me – is that it really taught me how to look at objects and understand them. I look first; I don’t fit the framework to the object or the history to the object. I try to read the object. That probably was the greatest benefit and that really came from having two great teachers: Karen Finch and Stella Mary Newton. Today, I think there’s an assumption that you get your MA and there’s a direct path – but you may have to segue and move sideways. Always plan ahead and think about your career path and what will distinguish you from other candidates.

Interview transcribed by Jennifer Potter with Joanna Fulginiti (Administrative Assistant, Costumes & Textiles, Philadelphia Museum of Art), March 19, 2014.