Photography often failed to be recognised as a true art form, something that has resonated with the struggles encountered by many famous photographers nowadays. The medium’s strength was always recognised in its ability to accurately represent reality – nevertheless, even reality has numerous depictions.

Gordon Parks is nowadays known to be one of the most influential photographers of his period. Having shot both fashion and news, he has an ability to convey beauty and despair in even the simplest of things. During our trip to New York in February just before Covid-19, our MA class was fortunate enough to have the chance to discuss photography with Michael Mery from the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. Amongst the treasure troves were coloured prints of one of my favourite photographers, Gordon Parks.

The beauty and the timelessness of his images highlight the incredible fashion that ornate the bodies in town. By opting for Kodachrome, Parks manages to render mesmerising compositions highlighting colours, motifs and textures of dress, bringing them to life before our very eyes. In peering into these individuals’ everyday life, one experiences an almost soothing feeling. Yet, it is this calmness that is ultimately most disturbing.

Coloured film enabled him to capture reality more accurately, but this only emphasised the obvious forms of discrimination present in these images. Amongst Parks’s pictures of people going about their everyday life, you catch glimpses of signs: ‘coloured entrance’, ‘colored’, ‘coloured only’. It becomes ironic that the coloured medium through which he captures these images resonates with the display of ‘coloured’ segregation encountered everyday by these same individuals.

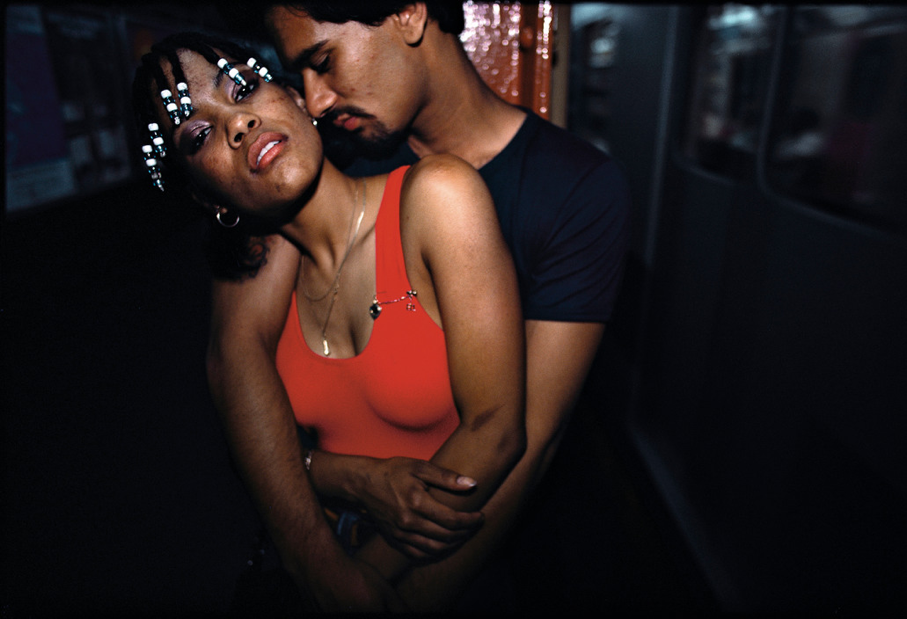

His work in some way can be compared to that of photographer Jamel Shabazz, another favourite of mine. Despite generations separating the two photographers, in some way both their colour series resemble one another; their use of subdued colours, individuals getting caught in the moment, a sense of innocence. As discussed by Parks in his autobiography, photography was ‘a choice of weapon’ – instead of fighting inequality with guns and violence, he ‘shot’ people through his lens just like Shabazz.

Earlier in June I tuned into a discussion with Shabazz organised by Nights Global, and one question kept coming up again and again -where is the love in today’s culture? I understand that I will never understand, but what I can recognise is that both Park and Shabazz are depicting just that: the need for love. Displaying how these individuals go about their daily lives, these two men use photography to document beauty and a humanity which appears to be taken away.

There is obviously much more that can be said and discussed in the works of the photographers mentioned above. But all in all, in the current ongoing media culture where people are constantly bombarded with the same images, often embedded with violence and aggression, recognising these images are as crucial as recognising those. They both show the same reality, just differently.