Norman Parkinson’s fashion photographs are imbued with contradictions. His ‘action realist’ images juxtapose narratives of fantasy. He pioneered dynamic depictions of women in motion yet excelled in his arrangements of the female body in quiet moments of poised and pensive stillness. Despite Parkinson’s seven-decade career, his contemporary Cecil Beaton credited his ability to reinvent his photographic style ‘according to the necessities of the day.’ However, Parkinson was a self-proclaimed nostalgic photographer, admitting ‘nostalgia is for me one of the great emotions, I have to edit this tendency a bit’. Nostalgia permeates Parkinson’s fashion photography, hidden within his characteristically colourful and energetic compositions, which distinguished him from his contemporaries.

A flame-haired figure with a lily-white complexion, seemingly floating on an ocean of textiles, stretches her limbs as if in a fairy-tale slumber. Nicky Samuel, a socialite and wife to the owner of Granny Takes a Trip boutique, drapes herself across her richly furnished interior space. Parkinson scatters visual clues throughout the composition to create a sense of unease; a corkscrew and two empty glasses perhaps hint to hedonistic over-indulgence whilst also revealing that she is not alone. A discarded copy of Hollywood Babylon (a controversial exposé of Hollywood’s sordid underbelly of sex scandals and mysterious murders) transforms her dishevelled slumber into something more sinister. The lilies that tower over her, inevitably staining her porcelain face with sickly pollen, symbolise both purity and death.

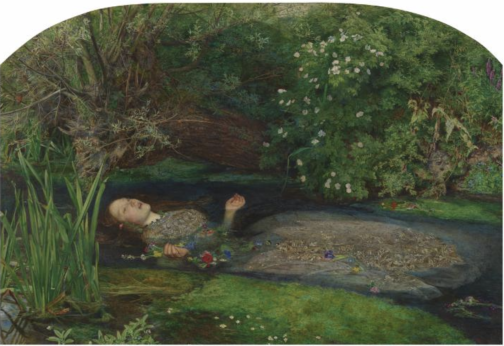

In the late 60s and early 70s, the misty medievalism and mythology of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, the Victorian art movement, wafted into contemporary consciousness. This nostalgic influence was evidently not lost on Parkinson. The impression of submersion, the floral motifs, Samuel’s Pre-Raphaelite characteristics and the morbid undertones of the composition all call to mind John Everett Millais’s Ophelia. However, featured in British Vogue in December 1972, Parkinson’s image indicates how casually Pre-Raphaelite iconography seeped into fashion contexts from the late 1960s onwards. The similarities between Parkinson’s image of Samuel and Millais’ Ophelia are potentially non-coincidental. Although Pre-Raphaelite art had remained largely unpopular up until its revival in the 1960s, a 1967 exhibition of Millais’s work at the Royal Academy would have brought him, and Ophelia, to the forefront of contemporary artistic culture.

Direct comparisons can be drawn between Samuel and Ophelia. Both are seemingly floating atop a surface punctuated by flowers. While Ophelia’s saturated gown drags her into the watery abyss of death, Samuel’s heavily patterned chiffon dress, designed by Ossie Clark and Celia Birtwell, drowns her body in bold tulips and pulls her deeper into the ripples of patterns. Like the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood’s ‘truth to nature’ philosophy, Parkinson was ‘not interested in anything that nature hasn’t smiled upon’, and he was reluctant to retouch his prints. Parkinson’s ability to capture the wider nostalgic resurgence of Pre-Raphaelite art in the 60s and 70s infuses his composition with a desire to return to a realm far removed from the synthetic modernity of post-war Britain. Yet, despite the arguably sinister undertones of Parkinson’s composition, there is something comforting in Samuel’s doll-like appearance and the ease of her lethargic pose.

Parkinson’s childhood memories of time spent in the countryside, espying ‘girls with loose dresses and a minimum of underclothes…lying around the lawn with languorous ease’ potentially informed his depiction of Nicky Samuel. Parkinson himself attests to this, stating that, throughout his career, ‘I photographed the memory of those well-observed weekend girls that I had seen through the fence’. This indicates that Parkinson’s photography is consciously informed by his nostalgic, and perhaps voyeuristic, tendencies.

Robin Muir argues that Parkinson ‘effortlessly transferred the spirit of neo-romantic pastoralism into a resolutely urban environment’. This is perhaps applicable to his depiction of Samuel, given that she is situated within her Chelsea home. Parkinson’s ability to bring the outdoors into the domestic realm conveys a suspension of reality. Parkinson himself claimed that ‘if you are going to be an artist – even a photographer – I think you have to major in fantasy.’

Furthermore, Parkinson’s portrayal of Samuel also mirrors his image from a 1956 location shoot in India for British Vogue. Like Samuel and Ophelia, model Barbara Mullen lies atop a watery expanse, in this case Dal Lake in Kashmir, laced with tulips, lilies and other exotic flowers. The dappled sunlight on the otherwise pristine surface of the lake reflects the clouded pattern of her dress. Yet, like Millais’ Ophelia, there are morbid undertones to this image. Mullen’s indifferent gaze into the middle distance and her partial submersion render her body totally passive. The boat on which she lies is obscured by, and overflowing with, flowers, which perhaps calls to mind a funeral boat. However, this image epitomises Parkinson’s excessively glamorous overseas fashion shoots in a time when long-haul travel was still fledgling.

Parkinson’s saturated use of colour is also notable. It wasn’t until the mid 1970s that he was working almost exclusively in colour, and this vibrant image from 1956 would have been situated among the largely black and white pages of British Vogue. Parkinson himself stated ‘I’m sure all the best photographers use black and white, but… I dream in colour…for me colour has always held more magic,’ which further hints to the degree of fantasy that underlined much of his work.

In his depiction of Nicky Samuel, Parkinson’s composition not only embodies the nostalgic fascination with the Pre-Raphaelites that resurged during the late 1960s, but also his nostalgic twinge for his idyllic childhood and his own photographic oeuvre.

By Claudia Stanley

Sources:

Anon., ‘Precious Original: Augustus John’s Chelsea Studio Regenerated by Nicola Weymouth’, British Vogue, No. 15, Vol. 129 (London, December 1972), pp. 128-129

Louise Baring, Norman Parkinson: A Very British Glamour (New York, 2009)

Robin Muir, Norman Parkinson: Portraits in Fashion (London, 2004)

Lucy Paquette, ‘James Tissot and the Revival of Victorian Art in the 1960s’. The Hammock (July 2004) https://thehammocknovel.wordpress.com/2014/07/31/james-tissot-and-the-revival-of-victorian-art-in-the-1960s/ accessed 29/03/22)

Norman Parkinson, Lifework (London, 1986)