I’ve been engaged by the Courtauld on one of its digital internships since August of last year, and in the two and a half years prior to that, I was a volunteer on the Conway Library digitisation project, clocking up over 250 hours either side of the pandemic.

My background is not what you might expect from someone in my position – I’ve done two tours of duty in broadcasting, in both production and administration capacities, and I was a market research coder for more than a decade in the days when surveys were mostly completed on paper.

Regarding the internship, the intention was that I would assist with preparing image metadata prior to the Conway Library being uploaded; however, very early on, Tom encouraged each intern to find a small project to work on. It was suggested that my small project could be the 19th Century Prints collection – and nearly a full year later I’m still working on it.

The first issue was locating the entire collection. A large part of it, covering about 140 boxes, had been accessioned to a degree some years back, but there were another 15 boxes of mixed content on another shelf that had barely been looked at. Then several boxes of unsorted prints from John Bilson’s collection were located. Then some oversized prints in Melinex pouches were located a shelf or two down, followed by another bunch located just at the very moment when I thought I was finally ready to get everything in some sort of order.

Then I looked at the spreadsheet containing the data from the prints already accessioned.

Up to that point, accessioning had been done very literally – everything on the mount and on the image had been entered into the spreadsheet largely verbatim. Many descriptions that were not in English had not been translated, architects were frequently listed in the photographer column, and if there was nothing but a town or city written on the mount that was all that had been entered, even if the image was of a specific building. Photographic credits that were embossed on the mount or image had not been listed, presumably because nobody was looking out for them.

Buildings such as ecclesiastical premises and town halls were listed under numerous names in anything up to four different languages. It was clear that, in order to ensure images of the same building were kept together, some standardization of the information on the spreadsheet would need to be performed before the missing images were added, well before any reordering or renumbering took place. Also, anything that made no sense or was incomplete was flagged for special attention.

Aside from images in one city being split between two folders in different boxes – one listed under the city’s English name and the other in its native form – there were other glaring issues with the way the collection had been boxed that required resolution. An entire collection meant to be ordered alphabetically began with a box marked ‘Algeria, Morocco and Peru’, for some reason. Another box randomly paired Holland – rather than the Netherlands – with Denmark. The part of the collection dealing with England veered from cities to counties and back again and the box marked ‘England S-Z’ had the helpful addition of the words “excluding Wales”. Well, it would, wouldn’t it? That said, the folder marked “Wales” was, rather confusingly, to be found in that very box.

The numbering of images went awry in the third box. There had been no standard method of numbering mounts with multiple images on one side or an image on both the front and reverse – sometimes they were given consecutive numbers, sometimes the same number with a alpha suffix. One particular folder contained 34 images, all of which had been given the same number with a numerical suffix from 1 to 34.

After consulting with Tom, the decision was taken to start again. Not only would there be a need to add the many images that had not already been accessioned to existing folders and boxes, with images being re-ordered and renumbered accordingly, but some ground rules would need to be set about how individual buildings would be listed.

As volunteers had already been adding biographies for photographers with content in the Conway Library to Wikipedia, it was decided that, wherever possible, a building should be listed on the spreadsheet by how it appears on English Wikipedia. If no entry existed for the building on English Wikipedia, it was decided to use the name listed on the native Wikipedia entry. In cases where a building was not listed on Wikipedia at all, it was decided to search for an official website or a listing on a local government website, or, failing that, establish a clear consensus from looking at other reputable websites.

Sometimes an alternative name or a native name has been added to the spreadsheet in parentheses, and once the images are digitized and uploaded alongside the descriptions, it should be possible to add all alternative names for a building, particularly ecclesiastical premises and Italian palazzi, as well a full timeline of changes to building names or uses, to all applicable images with some form of global edit.

At the end of January, with all located images accounted for in the spreadsheet, and three-quarters of the images previously marked as “missing” located in various nooks and crannies, the reordering, renumbering, and re-boxing of the collection finally commenced.

And that was where the fun really started.

First off, it was decided that the collection would be split between prints that could fit in our standard red boxes without folding and oversized prints, which would be kept separate. Previously, some of these folded images were kept in the boxes, while others remained loose. Our thinking was that one photographic studio could handle the content in the boxes, without having to adjust the focal length, while the second studio could handle content where the focal length and focus would need to be adjusted for every shot. Currently, the boxed images outnumber the oversized ones by about five-to-one.

It seemed to me that uploading an image of a building onto an internet database with only a city for identification may be considered somewhat inertial, so I decided early on to try, wherever possible, to locate and/or verify the locations featured in every architectural image in the collection, which make up most of its total sample of 10,500 individual images. For example, if a named building was listed purely as an “exterior” shot, could a more precise description be added – a façade, an angle of view, even the location from which the image was shot, if that could be determined. Was it worth pointing out other landmarks adjacent to the focal point of the image, or in the background? Could I determine a building from a close-up of a balcony or balustrade, a column or capital, a pier or a pilaster? Sometimes yes, sometimes no.

With a little bit of searching, images featuring a specific frontage that were previously described as street scenes could be pinpointed, such as Dante’s birthplace in Florence. An image previously thought to be of Rotterdam was proved to be of a canal in Amsterdam that has since been filled in, merely by locating a recent photo on, of all places, Trip Advisor, identifying a rooftop, a bridge and a particularly decorative street lamp, and then verifying the location on Google Maps, because, as any fule no, one shouldn’t assume that what one finds on the internet at first time of looking is any more accurate than what one already has to hand.

Aside from pinpointing locations and buildings featured in images that would have been close to impossible in pre-internet days, even for someone with a specialist knowledge of a particular geographical area, and possibly even for natives, it has also been possible to correct errors and confirm descriptions that have been adorned with a question mark, perhaps for several decades.

Over the last couple of weeks, I’ve been accessioning the last half-dozen boxes of Italian architecture, specifically Venice, which had more than its fair share of questionable filing and misleading descriptions.

These included:

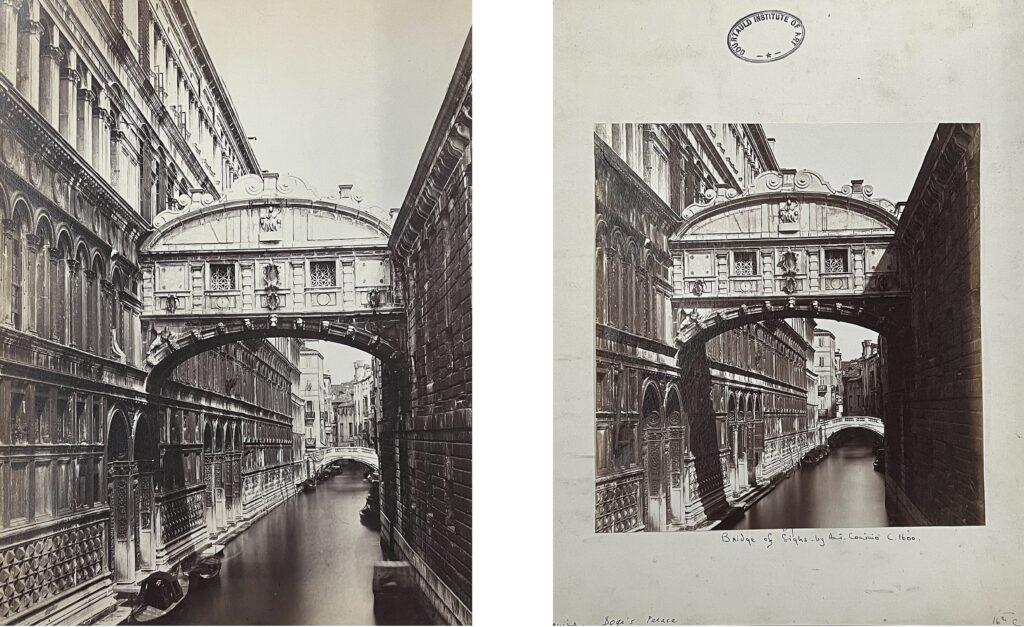

- Two close-up shots of the Bridge of Sighs [both sides of 5275] filed with images of the Doge’s Palace, when two more distant shots of the bridge [including 5274] were in a dedicated folder but had been accessioned on the spreadsheet under the name of the canal, Rio di Palazzo Ducale. One of the images itself is even mislabelled, claiming the picture was taken from one bridge when in fact it was taken from the next bridge along. And, to make things even more confusing, the Wikipedia entry also contains images that say they’re looking south when they’re actually looking north.

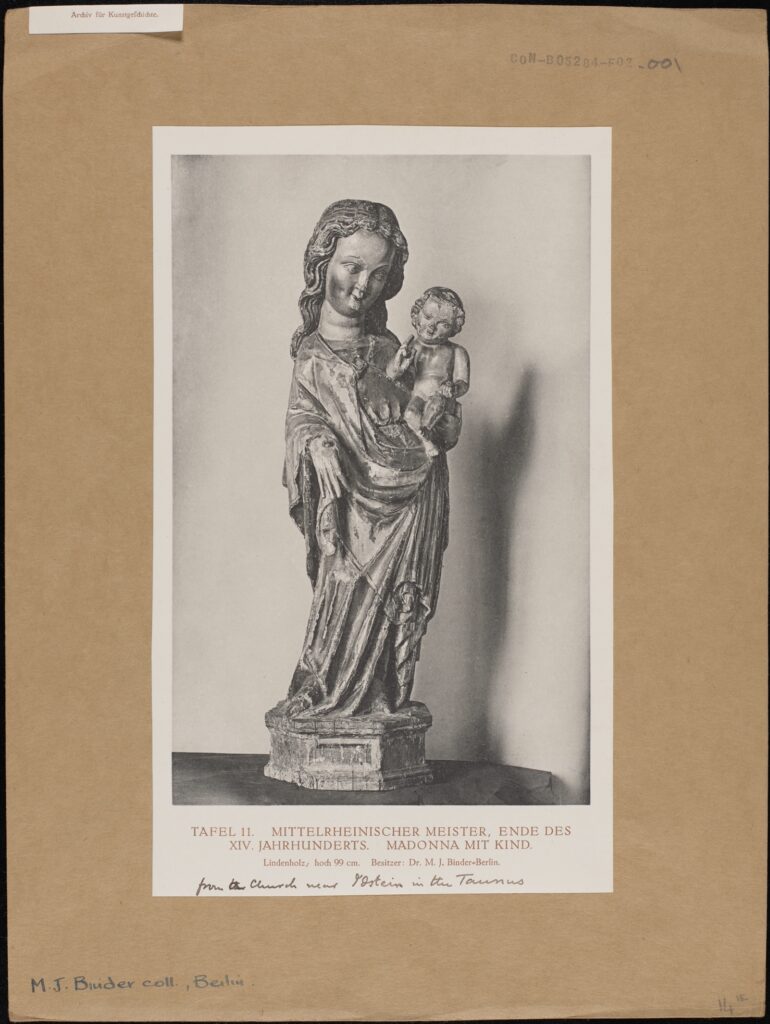

Fig. 1: Bridge of Sighs, Venice, Italy. 19th Century Print 5274, The Conway Library, The Courtauld Institute of Art, CC-BY-CC.

Fig. 2: Bridge of Sighs, Venice, Italy. 19th Century Print 5275a and 5275b, The Conway Library, The Courtauld Institute of Art, CC-BY-CC.

- A folder marked ‘Palazzo Vendramin Calergin’ contained eight images of two different buildings: six of Ca’ Vendramin Calergin on the Grand Canal [including 5193] and two of Ca’ Vendramin Zago, now the Hotel Ca’ Vendramin, on the Rio di Santa Fosca [including 5205].

Fig. 3: Ca’ Vendramin Calergin on the Grand Canal, Venice, Italy, 19th Century Print 5193, The Conway Library, The Courtauld Institute of Art, CC-BY-CC.

Fig. 4: Ca’ Vendramin Zago on the Rio di Santa Fosca, Venice, Italy, 19th Century Print 5205, The Conway Library, The Courtauld Institute of Art, CC-BY-CC.

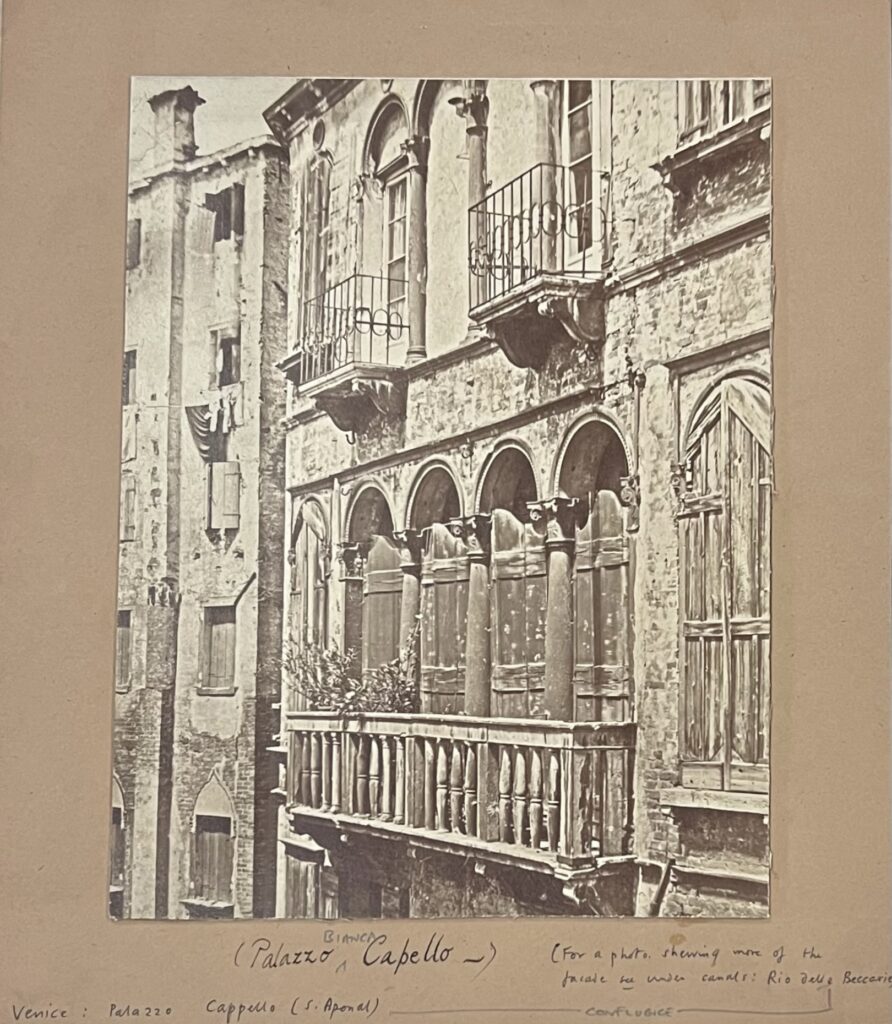

- An image marked ‘Palazzo Cappello’ [5208], when there are currently two buildings by that name in Venice, as well as six or seven others that carry the Cappello name in some shape or form. Wikipedia only had entries for two or three of these buildings, so whittling down the possibilities was tricky. Through a process of elimination and a battle with Google Maps, which is a nightmare to use for Venice – I don’t know why – it was established that the building was once known as the Palazzo Bianca Cappello, not to be confused with a Hotel of the same name a few doors down.

Fig. 5: Palazzo Bianca Capello, Venice, Italy, 19th Century Print 5208, Th Conway Library, The Courtauld Institute of Art, CC-BY-CC.

- There were several sets of different shots of the same building or buildings taken from virtually the same angle that had been filed in two or three different folders.

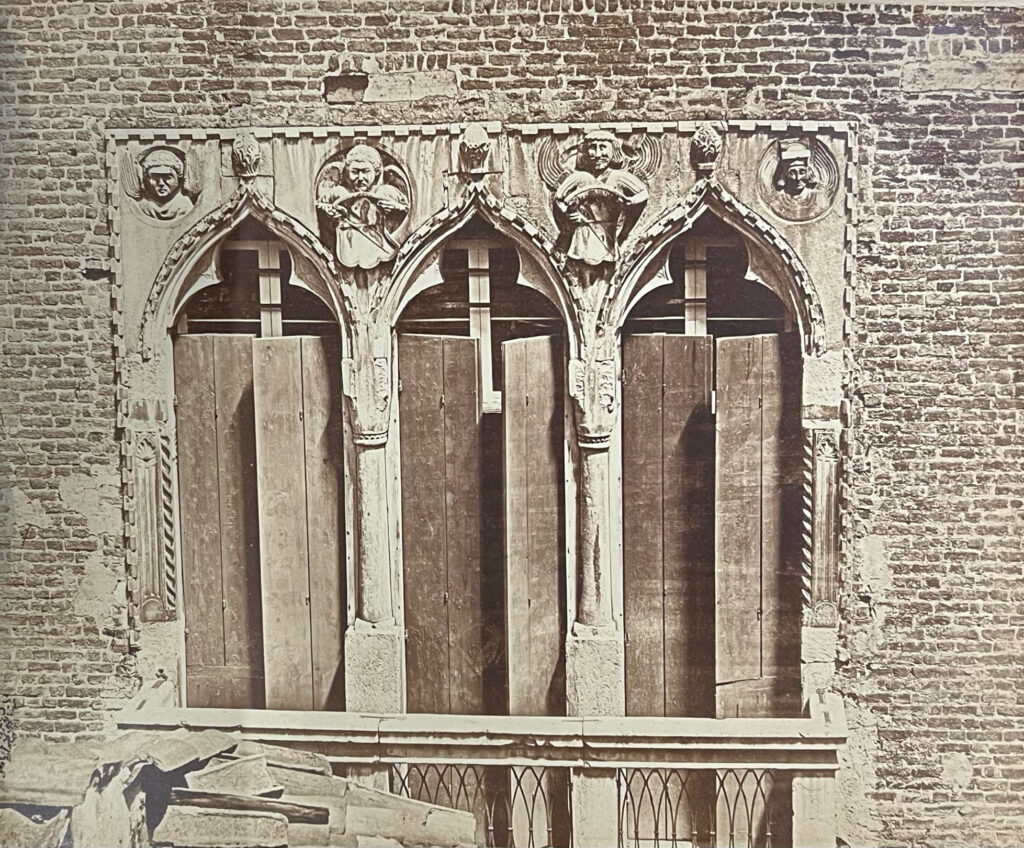

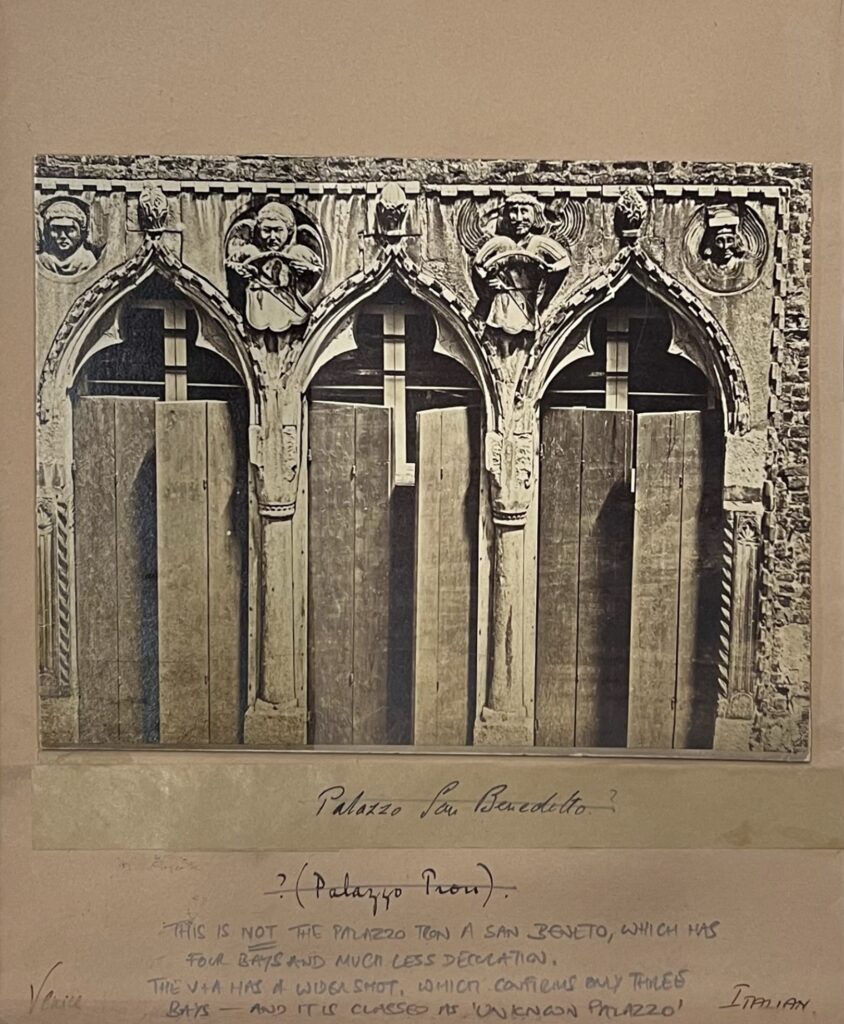

That is not to say that I’ve been able to identify everything. There are a couple of hundred prints from the previously unaccessioned sample that have absolutely no identifying information at all, as well as images of untraceable buildings in certain towns, cities and countries. Two such images were of the same building in Venice, yet were placed in different folders – one, inexplicably indexed under C, was of the “Palazzo Bordulmier” [5237], of which I could find no trace, and the other, indexed under S-Z was question marked as “Palazzo Tron” or “Palazzo San Benedetto” [5238] – probably the Palazzo Tron a San Beneto, which is similar but has four bays of windows, not three as pictured. A wider version of one of the two shots exists in the V&A catalogue, which list the location as unknown, so that’s how it’s been left in our database for now.

Fig. 6: Unknown, 19th Century Print 5237, The Conway Library, The Courtauld Institute of Art, CC-BY-CC.

Fig. 7: Unknown Palazzo, 19th Century Print 5238, The Conway Library, The Courtauld Institute of Art, CC-BY-CC.

There are also a few images where I’ve gone with the information provided on the mount but online research has provided more questions than answers. Hopefully, once these images are made available to the public there will be individuals out there who will be able to identify them and people at the Courtauld who will be able to verify that identification and update the record accordingly.

I hope that one of the main benefits of taking the time to research these prints in greater detail will be to make the searching easier for those who will be searching from their homes or places of study, rather than physically removing the box from a shelf in a library. The proof of the pudding, of course, will be in the eating, but what I’ve done is certainly an improvement on what we had for publication a year ago. And, as I alluded to earlier, it will invite users to suggest further contextual information that can be verified and added as and when.

There are plenty of images in this collection, as well as the Kersting collection and the wider Conway Library, that would benefit from being exhibited to the public and, where copyright permits, being made available to the public in the form of prints, either bespoke or off-the-peg, or in the form of other gifts, such as calendars or diaries or coffee-table books. Personally, I’d take a photo of a long-demolished London building over Van Gogh’s bandaged ear any day, but that’s just me.

I would also argue that further licensing opportunities may arise by establishing a proactive relationship with publishers of books and periodicals to establish whether there are titles in their pipelines that would benefit from the use of an image in which the Courtauld holds the necessary rights of exploitation, rather than waiting for an author or editor or production manager to request something, and having a clear and pre-established rate card that is appropriate for any and all uses.

Richard Cray

Courtauld Connects

Digitisation Project

Metadata Assistant