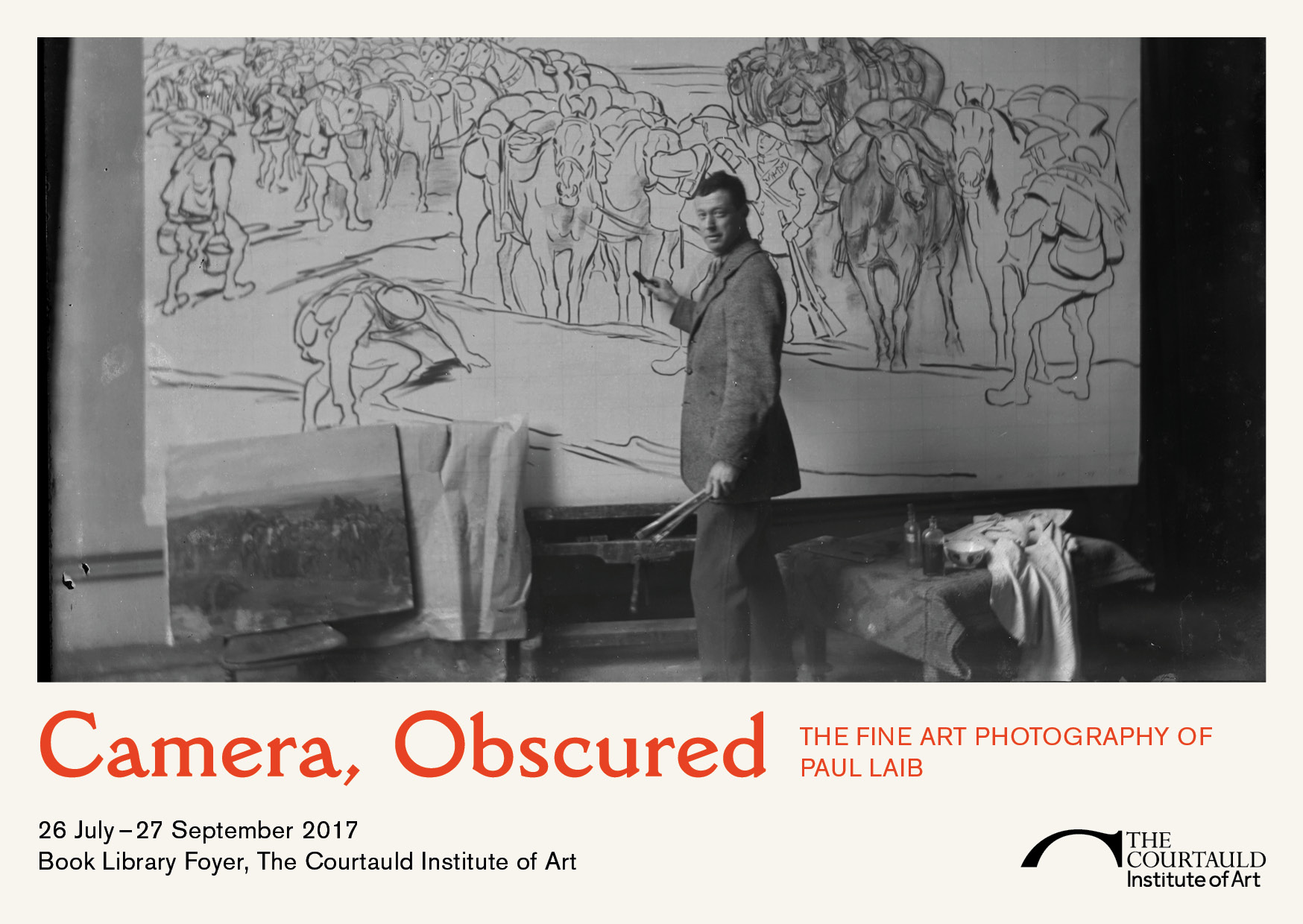

Paul Laib (1869-1958) was a photographer who in the early decades of the 20th century captured the works of some of the most important contemporary artists working in Britain between 1890 and 1950. His large corpus of over 20,000 negatives were gifted to the Courtauld in 1974 by Patrick de Laszlo, son of Philip de Laszlo, the famous portraitist who for many years had been Laib’s client. In 1933, Laib visited the studio of Barbara Hepworth and Ben Nicholson at ‘No. 7 The Mall’ in Parkhill Road near Hampstead. His collection of photographic glass plate negatives depicting the works and compositions of assorted objects in Hepworth’s and Nicholson’s artistic residence remain some of the most puzzling and charming images in the Courtauld’s vast photographic library. By accompanying these images with vivid poetic descriptions containing excerpts from Hepworth’s own writings and memoirs, this virtual exhibition hopes to shed light on the aesthetic significance of these objects for the artists’ developing views on sculpture, painting, form and space.

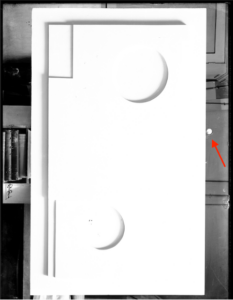

No. 7 The Mall studio, Hampstead, 1933. Photo by Paul Laib. The De Laszlo Collection of Paul Laib Negatives at The Courtauld, London.

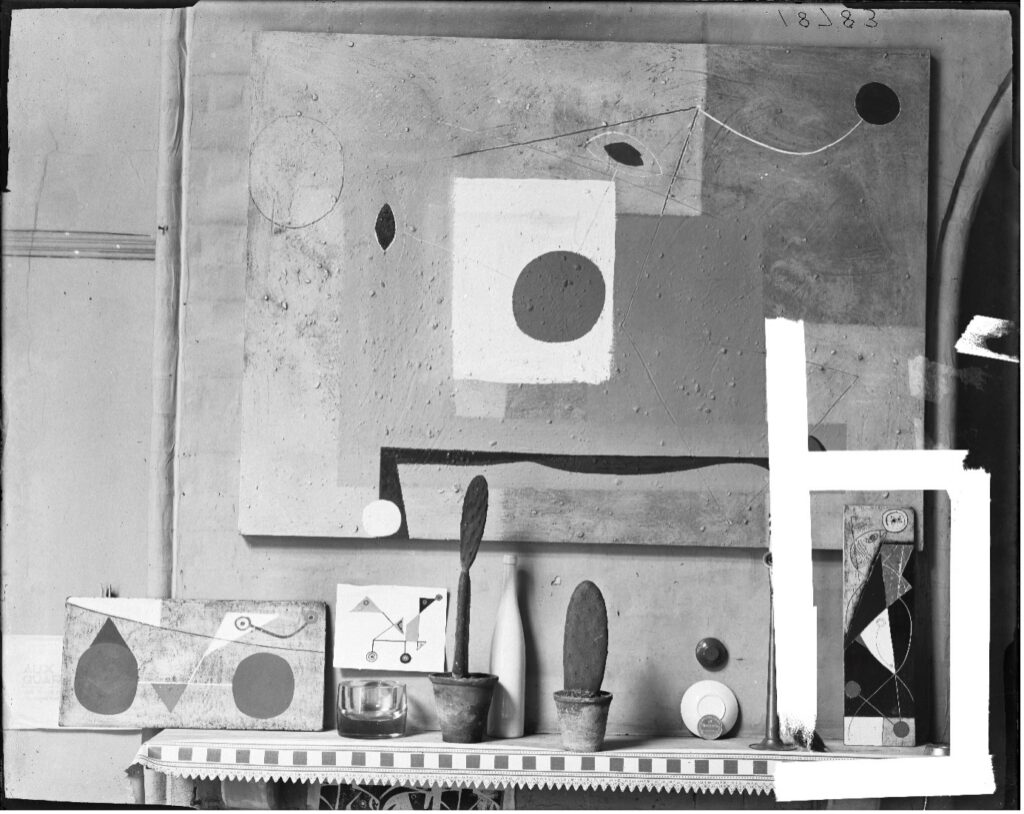

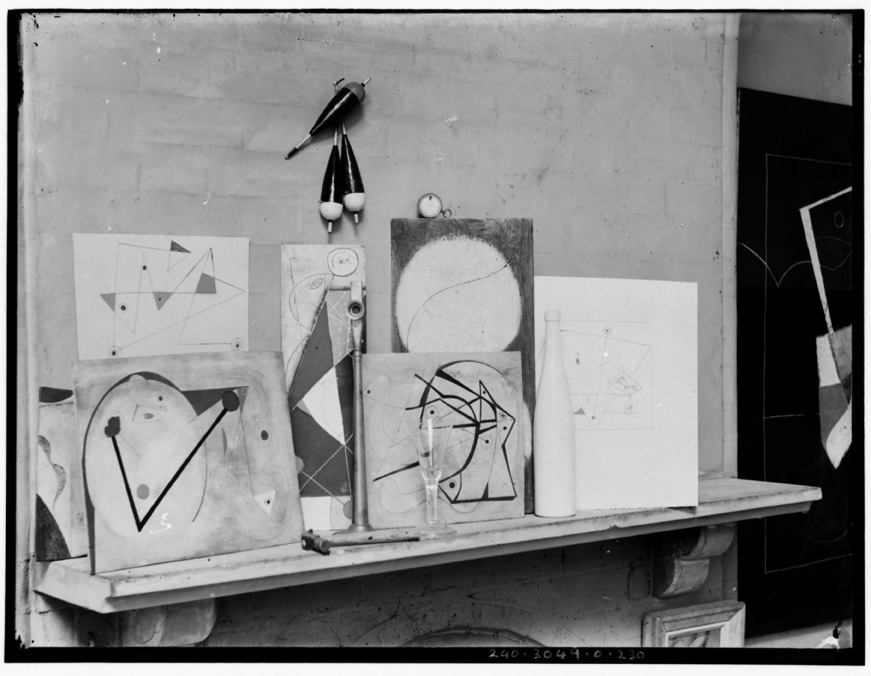

At first glance, the compositions from Laib’s photographs appeared to me almost as deliberate, still-life shots. The artworks depicted are embellished by the objects which encircle them: could this be the work of a photographer who is showcasing the art in its studio environment? Precariously balanced crockery gives the illusion of momentary arrangement. A slender white bottle reappears in different assemblages. Small level inclinometers, like elegantly shaped pocket-watches, litter our field of view, and are added and removed between each picture. The concept turned out to be as unlikely as it was originally alluring. Courtauld digitisation specialists suggested Laib would have been perhaps too shy and discreet in his operations to have meddled with the objects in a renowned artist’s home – as suggested by the darkness of his negatives, the Hungarian photographer was often hasty in providing his famed clients his service, leaving little time for his glass plates to be exposed by light through his camera. Upon closely reviewing Hepworth’s writings and meditations from her period with Nicholson, I increasingly came to understand the arrangements as compositional masterpieces, highly wrought visual works assembled by the artists and informed by their developing thoughts on the nature of form, abstraction, and space.

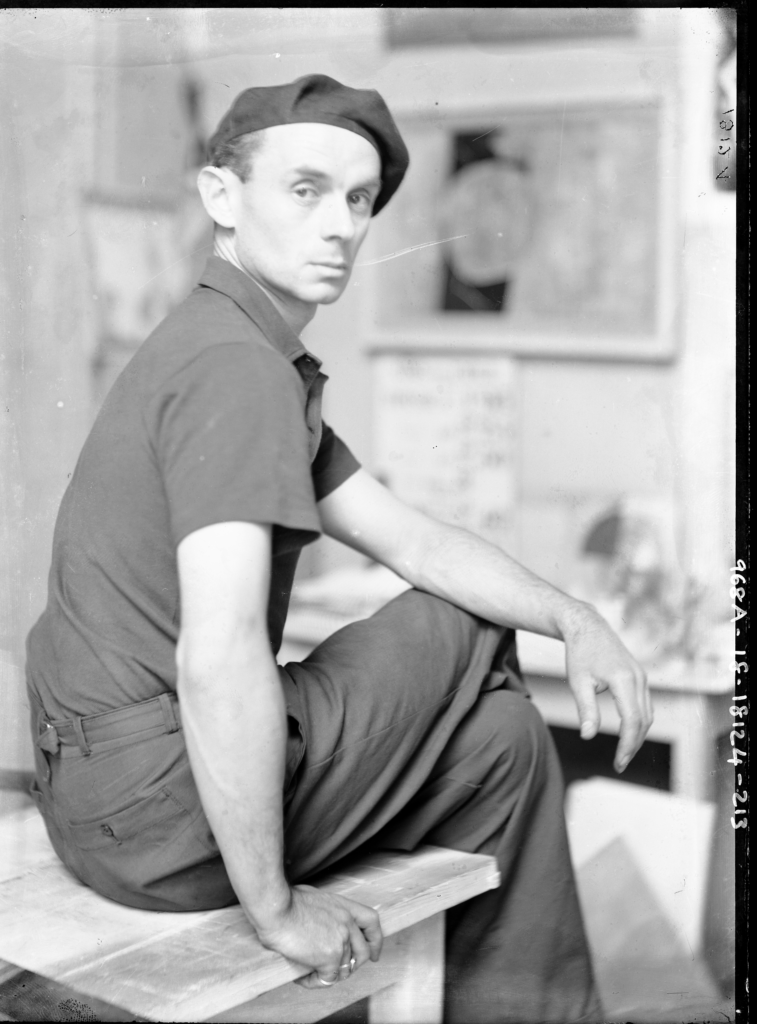

Portrait of Ben Nicholson, No. 7 The Mall studio, Hampstead, 1933. Photo by Paul Laib. The De Laszlo Collection of Paul Laib Negatives at The Courtauld, London.

Inclinometers being placed and removed between photographs, No. 7 The Mall studio, Hampstead, 1933. Photo by Paul Laib. The De Laszlo Collection of Paul Laib Negatives at The Courtauld, London.

The images taken by Laib present groups of objects, trinkets, souvenirs, and other puzzling paraphernalia. Presented on different planes and contrasting positions, these objects assume a life of their own, responding to each other in both thematic and formal qualities. Desert cacti are combined with wine bottles and fishing floats. A hammer is juxtaposed to a fragile glass. At the same time, the ensemble of curves, triangles and squares inherent in the objects’ outlines resemble those simplified in Nicholson’s geometrical works. A small coffee plate might for instance mirror an abstract gesso dot. The outline of a plant is reminiscent of his linocut profiles, and a protruding shelf or bookcase might match the indentations in his white, sculptural reliefs. These correspondences also reflect Hepworth’s interest in sculptural groups, which, like the duo’s object compositions, conversed in what Hepworth called “a silent language of forms”.[1]

No. 7 The Mall studio, Hampstead, 1933. Photo by Paul Laib. The De Laszlo Collection of Paul Laib Negatives at The Courtauld, London.

No. 7 The Mall studio, Hampstead, 1933. Photo by Paul Laib. The De Laszlo Collection of Paul Laib Negatives at The Courtauld, London.

Among the string of random articles assorted in careful balance, the artworks themselves feature as a reminder of their co-existence with these shapes. Some lie in the corners and borders of the composition. In other pictures, Nicholson’s linocuts provide a backdrop for the arrangement itself. Often, a sculpture or white relief might be the main photographed piece, but we gain access to the work’s close surroundings through the space left in the narrow margins of the picture. In some cases, the resemblance between the artwork and its formal environment is impossible to ignore. In Laib’s photographs of Hepworth’s studio, we witness the sculptures next to the shapes and objects which inspired them: “I like to have a lot of material lying about the studio for a long time – even for years – so that I feel intimate with each piece”(33). The artists wanted the works photographed in the context in which they were originally conceived, before they would be bought, framed, and displaced in the white-washed setting of a gallery or museum. In her writings, Hepworth explains that sculptures and other artistic creations are almost inseparable from its immediate surroundings, being conceived out of precise qualities found in nature or in one’s studio. Existing in a state of “harmony” with the other “individual forms which inspired it”, these are, as Hepworth claims, “for their own specific landscape”(134).

No. 7 The Mall studio, Hampstead, 1933. Photo by Paul Laib. The De Laszlo Collection of Paul Laib Negatives at The Courtauld, London.

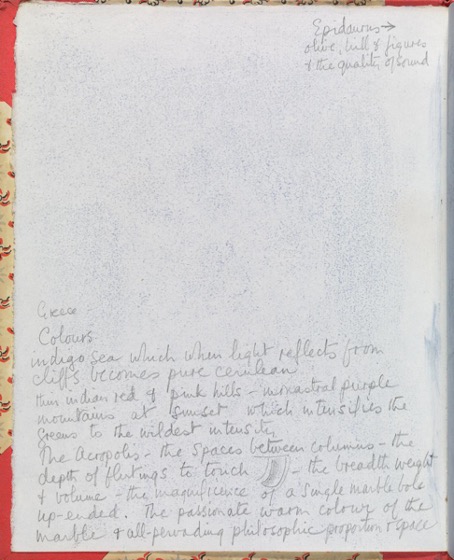

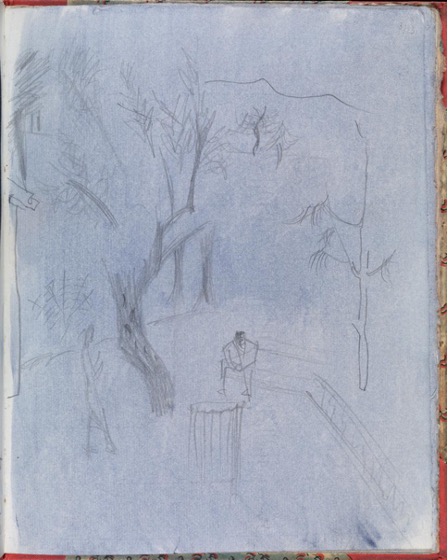

While the significance of Nicholson’s collection of everyday objects has been the subject of discussion in recent years (a 2021 Pallant House Gallery exhibition described these as “a source of almost endless inspiration for the artist”), Barbara Hepworth’s own fascination with spatial arrangement and object composition has been left relatively unobserved.[1] This is especially surprising given the wealth of literature on the subject: in her own writings and conversations (1930-1970), the sculptor makes ample reference to the significance of grouping objects into what she called “rhythmical” composition, a musical idea she applied to forms in natural landscapes as well as to the domestic environment of her home or studio. The impact of Ben Nicholson’s work, on the other hand, opens up for her a “new and imaginative approach to the object in landscape, or group in space”(61). The specific nature of the arrangements photographed by Laib are themselves described at length in Hepworth’s memoirs, in which the artist recalls the provenance and significance of certain objects for the artistic duo – objects which we can directly retrace to Laib’s images. Exceptionally fluent in communicating her aesthetic ideas, Hepworth was also particularly conscious of the transmedial nature of the arts, and where a sculpture, a studio, or an artwork is described, language from poetry and music is employed to articulate its significance. “Carving is, perhaps, more similar to music”. Art is the “perfect realisation of rhythm, composition, order and harmony”. Sculpture, on the other hand, is “dictated only by my poetic demands from the material”(43-68). Like few artists of her generation, Hepworth was also acutely aware of the expressive potential of poetic language in conveying abstract ideas. During her travels in Greece, she resorted to free-verse compositions to conjure the appearance of a natural landscape littered by marble forms. Her artistic beliefs are often expressed with the use of imaginative vocabulary and rhapsodical prose, both of which are referenced and integrated in the poetic works below. Throughout her life, Hepworth composed countless verses, many of which can be today found in Tate’s archive of unpublished manuscripts.

Epidaurus, 1954. Tate Archive. Dame Barbara Hepworth, Greek Sketchbook interleaved with pressed flowers and plants, Tate Britain.

Epidaurus, 1954. Tate Archive. Dame Barbara Hepworth, Greek Sketchbook interleaved with pressed flowers and plants, Tate Britain.

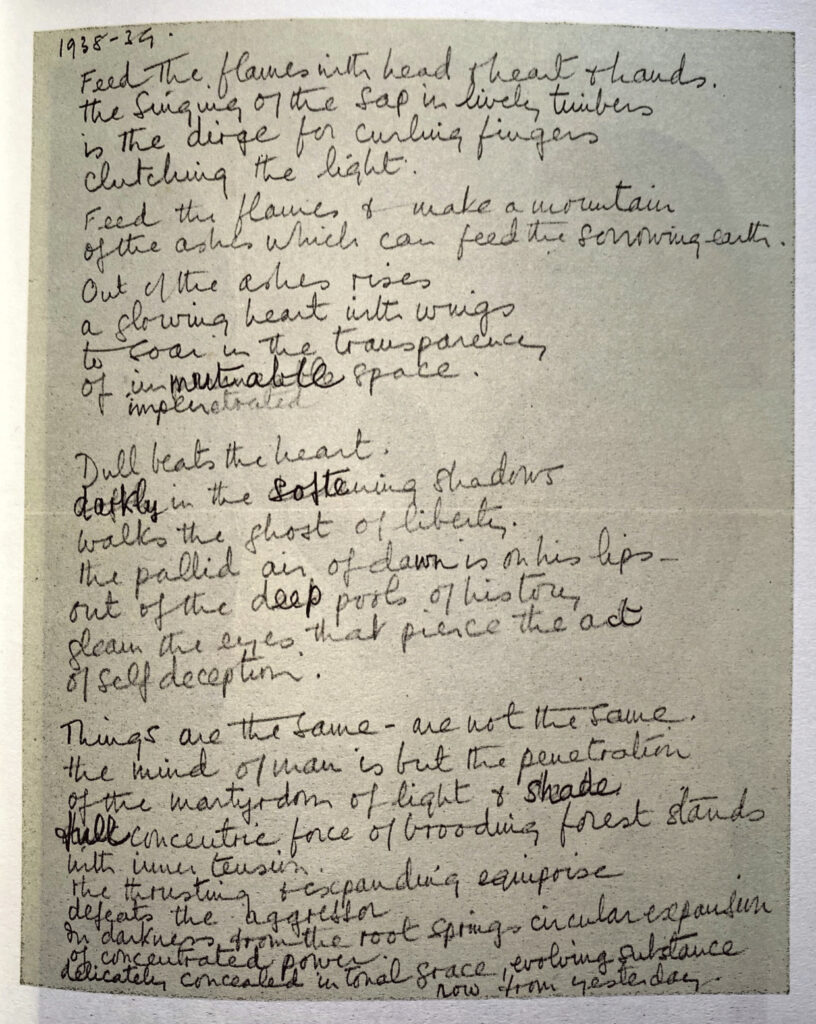

‘Feed the flame’, manuscript draft (earlier of two manuscripts), 1938-9. Tate Archive. Dame Barbara Hepworth, Handwritten notes by Barbara Hepworth, Tate Britain.

Honouring Hepworth’s fascination with poetry and its relationship to visual art, the following portfolio of ‘word-image’ compositions responds to Laib’s photographs through the creative use of poetic language, hoping to articulate the different forms of dialogue between the objects as well as the various interrelationships between the artworks and their immediate formal surroundings. A poem (by its broadest of definitions) can itself be understood as a thoughtful assemblage of single elements. Words, rhymes, assonances and line-breaks are all examples of single devices which amount to a larger, choral whole, giving a poem a sense of overall unity. Much like Hepworth and Nicholson’s own assemblages of selected objects, these participate in a greater “symphony”(56).

By incorporating direct allusions to Hepworth’s writings within the creative text, I hope to present the possibility of a ‘poetic exhibition’, whereby an informed, ekphrastic description (vivid, verbal account of a figurative work of art) is offered, as if to replace a museum caption or mere textual note. Inspired by a recent exhibition at the Courtauld which saw works by Peter Doig and poems by Saint Lucian writer Derek Walcott displayed side-by-side, this project hopes to demonstrate how a transmedial presentation of this kind could urge the viewer to establish a deeper connection with the inner themes and concepts underpinning a visual work of art. Without the constraints of prose syntax, I believe poetic language allows us to delve into the fluid and inarticulable concepts matured by the artists themselves in realising their compositions.

As one of the interns at the Courtauld, I was particularly drawn to the archive’s efforts to render the material qualities of the photographs perceptible in digital reproduction, the same way one would in attempting to digitise a Renaissance panel painting, or an Impressionist masterpiece. As a result, I have decided to accompany each of the poem titles with the original combination of numbers marked by Laib and previous archivists onto the negatives themselves, in an effort to highlight the material quality of the images as physical works of art.

I think every sculpture that’s made must have some relation to a place. I don’t think you can make it in a vacuum – at least, I can’t. It always has some kind of position in the landscape or in architecture, in one’s imagination.

— Barbara Hepworth in conversation with Reg Butler, Artists on Art, BBC Third Programme, Recorded in London, September 1951

And yet best critical account of a picture may well be that of a sonnet or of an elegy…

Charles Baudelaire, Salon de 1846

900-141-18124-874

A Large Rock

The whole great studio filled with soaring forms and still, quiet forms, all in a state of perfection in purpose and loving execution, whether they were in marble, brass, or wood… Everything I saw in the studio-workshop itself demonstrated this equilibrium between the works in progress and the finished sculptures round the walls, and also the humanism, which seemed intrinsic in all the forms.

— Barbara Hepworth on Constantin Brancusi’s Studio, The Poetry of a Figure in Landscape, London, 1931-34

No. 7 The Mall studio, Hampstead, 1933. Photo by Paul Laib. The De Laszlo Collection of Paul Laib Negatives at The Courtauld, London.

It is a nest of infinitesimal detail

which confronts us,

a temple of unparalleled creation.

Unformed asteroids rest in the foreground.

Sculptures are hallowed by morning light.

Imagine hands that, whirring,

conquer elements, carving,

cast unwieldly designs.

They are like plants propagating in a small solarium:

a strange verticality dominates the scene.

It is as though we witnessed the growth of a number of cylinders.

Here we observe not the instruction of forms,

but the destruction of laws into bare essences.

Why might a stool, placed on a stool, give the illusion of upward growth?

And why might a window, harbinger of light,

be reflective of the source of all things present?

We do not know, until a jagged rock dominates the scene.

A large rock, like a statue,

may “give the sense of a new enjoyment”,

Hepworth says, “when placed in a small room”.

It is “a new aesthetic experience which cannot be got

through any other kind of art”.

It is as though our hearts were invested in the future of these silhouettes.

We entertain the notion of scale by watching a rock create obliteration.

It is the uncivilised shape that we abhor, which like some cruel intruder

is uncouth among smooth stones we may very well hold,

pebbles which could fit in our palms.

“There is a symbolism, of course, in stone”.[1]

[3] Barbara Hepworth: Writings and Conversations, pg.36, 80

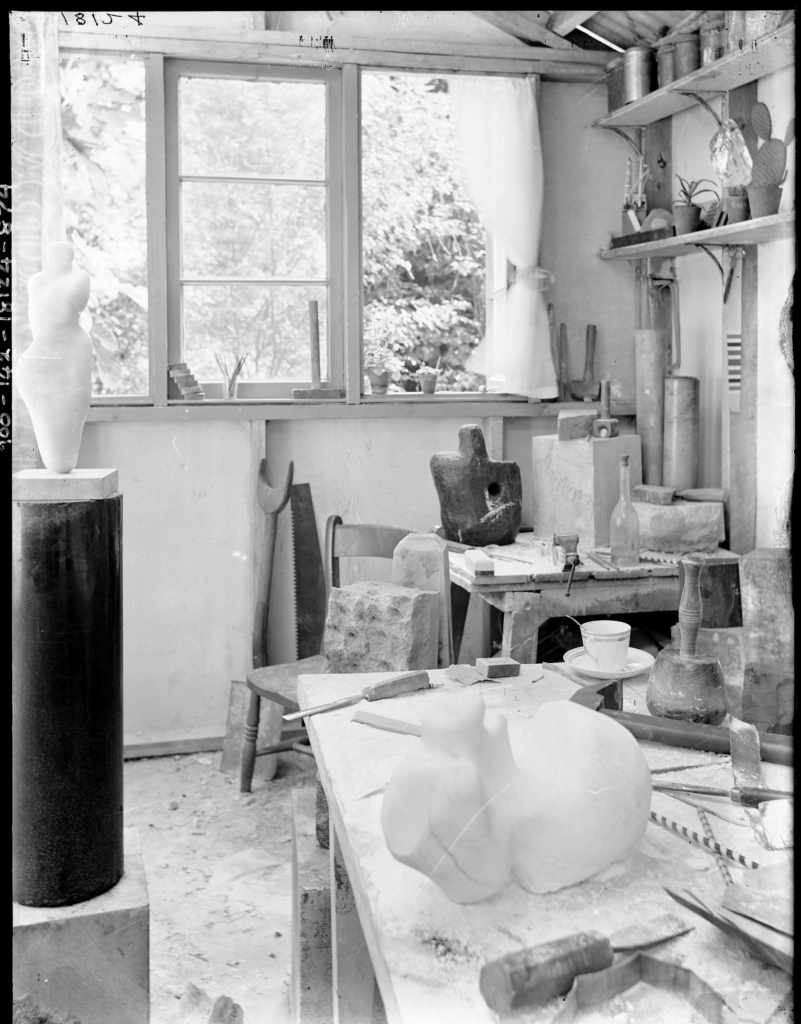

900-142-18124-874

Works by a Window

As regards lighting and setting for my work, I like as much light as can be obtained, and I like a feeling of space. This does not mean actual physical area, but more the feeling that one gets near a window where the eye travels outwards…

— B.H. in ‘Approach to Sculpture’, Studio, London, 1946

No. 7 The Mall studio, Hampstead, 1933. Photo by Paul Laib. The De Laszlo Collection of Paul Laib Negatives at The Courtauld, London.

I

These are the inhabitants which populate the corner.

We see them rearranged in newfangled order.

A festival of forms informs the surfaces in view,

and standing like some trilogy

of strange thematic symmetry,

three shapes among the objects make their central rendezvous.

II

The first, in opposition, lies reclined across a table,

surrounded by the tools which have enabled its creation.

An octagon of sorts imparts a rhythm of erosion,

a scalpel lies for indentations subtler than skin.

Beside a wedge a straw suggests the energy of suction –

a bell-like hammer sits behind, inverted, like a pin.

What is this creature, motionless and firm,

lying naked like the offspring of some bird?

Embryonic is the vein which cuts across the mineral

of a sculpture of full shape unknowable,

of scale unreconcilable.

It possesses the inevitable stumps of that which imitates humanity.

The marble remnants of a neck, the narrowing of abdomen –

its bowels could resemble both fertility and foetus.

A womb slackens laterally, conjoined, like a sack,

and lying on its back it rests on two bottom features.

“I find that it is possible to take

a pebble of fine and simple shape

and carve in addition successive planes

suggestive of the human form”.

Reclined across a table it retains its human form.

III

Our eyes observe a second shape of similar conception,

lit beneath the window, focused by the camera.

Dark and prehensile, volcanic and obsidian,

it was cast and preconceived with a meteoric cavity.

Obliquely it retains a kind of central torsion,

a motion, if you will,

akin to that of human shoulders,

of balanced contrapposto.

Around it are a number of identities,

illumined by the light which gives full play to its concavities.

A glass transparent bottle, shaped like a lute –

symphonic in its similar appearance to a torso.

Inverted hammers play an inane game of balance –

as do the saw and the crutch, which touch, amiably.

Marble slabs and rectangles surround it here and there,

some strewn across a table, a few erected by a chair.

What is the hole pierced into it

if not an exploration into “the special accord”

between the “inside and outside in every form”?

A “nut in its shell”, a “child inside its womb”,

the shape of “shells and crystals”

and “the architecture of human bones”?

“Every shadow, cast by the sun from an ever-varying angle

reveals the harmony of the inside to outside”,

gives the eyes their “tactile perception”,

reveals “the interplay between space and volume”.

Stark and dark and hollow

and with a hole pierced into it,

the figure faces us, illumined

on a far corner of the table.

IV

We need not search for the third sculpture,

as it stands so high above the others on a tower

of cylindric proportions – of diminishing dimensions.

From the bottom to the top,

cubes and blocks and cylinders

decline.

The figure at the top is stupefyingly streamlined, a body so round

its sound could be akin to that of a guitar, or of a globular cello –

its shape to Donatello’s David and the nudes in the Bargello.

“Growth, movement and balance.

All these things interlock,

and are principles which,

when expressed aesthetically,

do re-create a vitality…

There is life in stone and in wood”.[3]

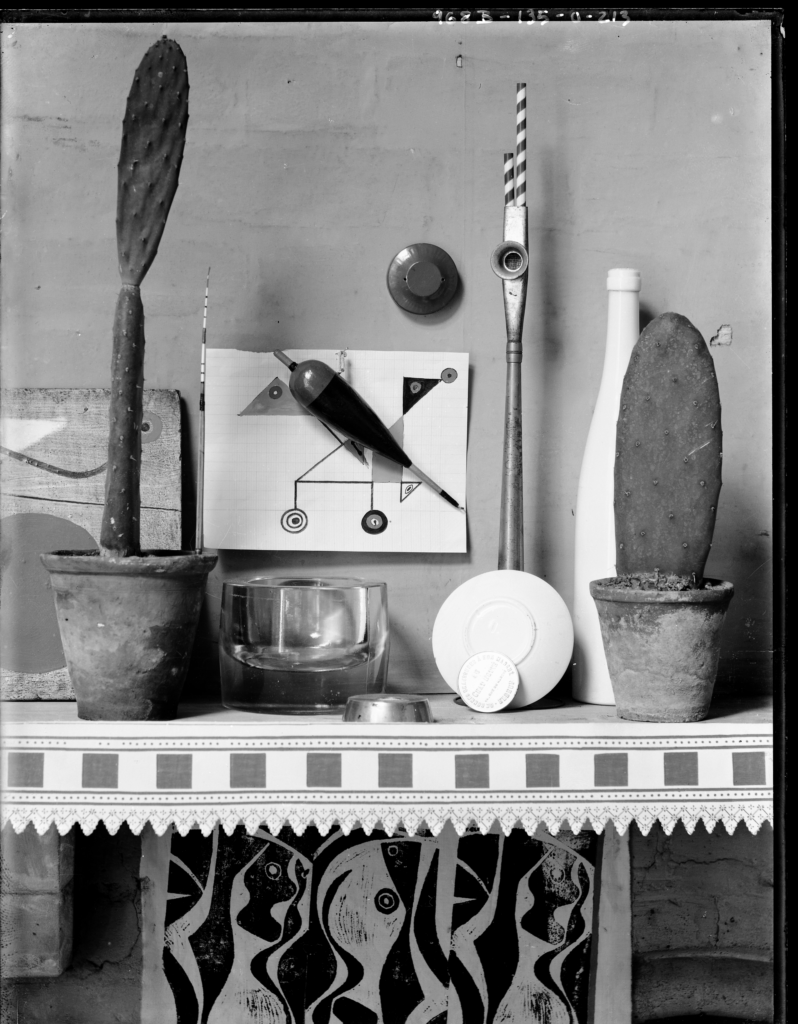

968B-135-0-213

Cactus Compositions

Small things are found and kept for their lovely shape, their weight, their texture and intense pure colour. Objects that we place near to each other, in their different aspects and relationships create new experience. A scarlet circle on the wall, a slender white bottle on a shelf near it, a bright blue box and lovely-shaped fishing floats that rest in the hand like a bird, weighty pebbles, dull grey, some gleaming white all these move about the room and as they are placed, make the room gay or serious or bright as a frosty morning …

– B.H. on the objects in the Mall Studio, Unit 1: The Modern Movement in British Architecture, Painting and Sculpture, London, 1934

No. 7 The Mall studio, Hampstead, 1933. Photo by Paul Laib. The De Laszlo Collection of Paul Laib Negatives at The Courtauld, London.

This is perhaps the most exquisite of constructions:

a study of form and shape in its basic rudimentariness.

Geometries commingle making complex combinations.

The pattern on the table like a crossing in the street.

One questions if the artwork in the middle is the feat

or if the objects are abstractions in the artworks made concrete.

Plates and plants and flowerpots repeat the shapes on paper:

a shoe-polish, from CHAT BOTTÉ,

CHAUSSURES A BONNE MARCHÉ,

retells the forms and radii of small concentric circles.

A fishing rod, a line, a pipe with straws inside:

these mirror the strange nexus of connections drawn behind.

Correspondence is the visual key.

And veritably we find in these very same objects

an equal desire for growth and formal structure,

to grow, to breathe, to change and think – respire,

and for an upward momentum, comparable to sculpture.

Desert cacti are like flags, erect in planets of creation.

A bottleneck aspires to a higher order, something different:

organic, complete.

A strung-up fishing float (perched on a diagonal)

hovers in the foreground like some bird.

These are planes and patterns that intersect,

orbiting geometries and shapes

so close to one another they hold

a gravity and discover thus

their role in formal landscape:

“the balance of one form poised against another form”.[4]

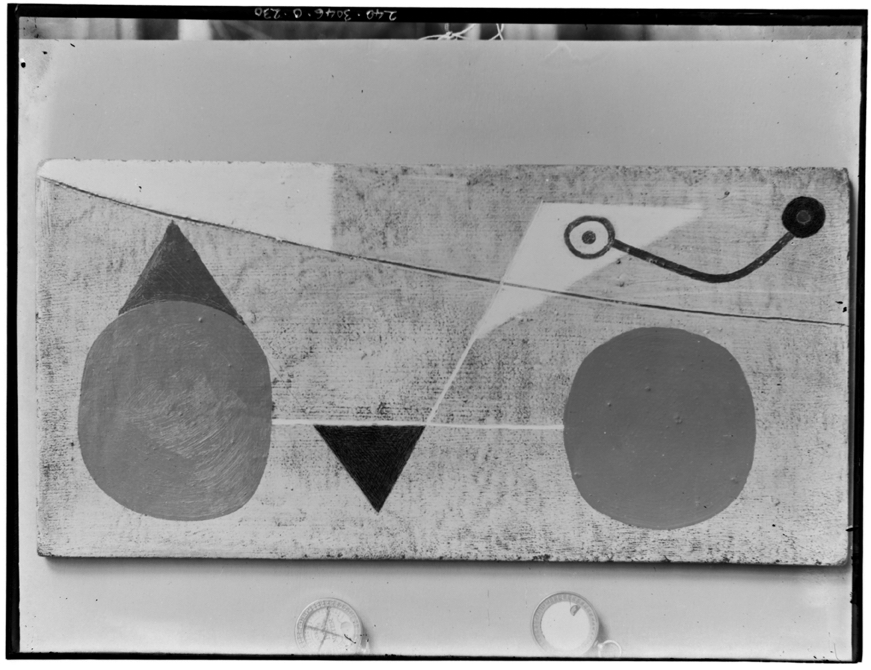

240-3046-0-230

Lino Cut Inclinometer

I was fascinated by Miro’s unique way of picking up pebbles on the beach and arranging them swiftly so that his gesture revealed a Miro painting in movement.

— B.H. on Miró, Constructive Forms and Poetic Structure, 1934-39

No. 7 The Mall studio, Hampstead, 1933. Photo by Paul Laib. The De Laszlo Collection of Paul Laib Negatives at The Courtauld, London.

This picture consists of impossible equivalence:

a strange delusion of the simpleness of shapes.

It is the image in geometric resolution,

a pun between the circle and triangle in space.

Across a wooden linocut,

lines project illusions of awkward equilibriums,

each barely managed, obdurately upheld.

They are the chair and the window conceptualised,

the tablecloth abstracted,

the bonnet reimagined.

It is as though two people enjoyed lunch

in a strange visual paradigm.

In a corner, two spheres, like eyes,

assess each other’s weight

through the value of a string.

And it is in this world of correspondences

two inclinometers appear, outside –

giving almost the impression of time,

or of time petrified.

And we relish in their form

and the rings bound to them,

repeating the reprise of the painted correspondences.

Objects, reduced to the simplest of essences,

Inflect their presence through proximity and incidence.

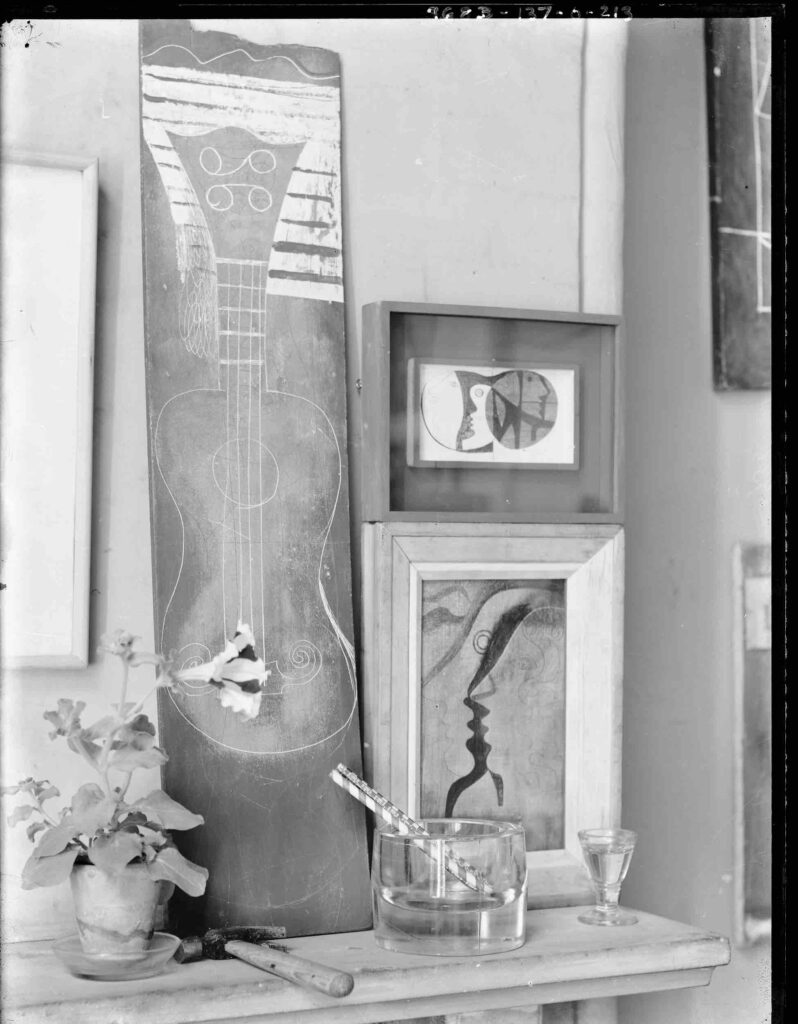

968B-137-0-213

Guitar

The impact of Ben Nicholson’s work had a deep effect on me, opening up a new and imaginative approach to the object in landscape, or group in space, and a free conception of colour and form.

– B.H. on the objects in the Mall Studio, Unit 1: The Modern Movement in British Architecture, Painting and Sculpture, London, 1934

No. 7 The Mall studio, Hampstead, 1933. Photo by Paul Laib. The De Laszlo Collection of Paul Laib Negatives at The Courtauld, London.

This image is another of a series of assemblages,

a thoughtful merging of amusing situations.

Among a stray ashtray, a number of things remain.

A flower strokes the contents of a strung guitar,

like a plectrum reflective of what these things are,

or might in fact turn out to be.

Overlapping profiles are marked by a total blackness.

A guitar could entertain the serenading of a kiss.

Its shape is made on the basis of sweet

vacancies and rhythm,

absorbed into sensations

of leisure and delight.

Lyrical lines characterise

both linocuts and profiles,

the silhouettes and spheres

which meet the patterns on the instrument.

The sound between the pictures

is of poetic predilection:

like words and punctuation

they are marked by gradual intervals.

The sentence they assemble

is a visual figuration.

The wooden panel,

warped like an oar,

cut like a byzantine relic,

is alighted on a table,

where a glass of water meets an adjacent ashtray,

shimmering with similar reflections.

Half-full, half-empty, it produces new illusions.

968A-15-0-213

Profiles by a Flowerpot

A sculpture, as I conceive it, is for a specific landscape. My own awareness of the structure of the landscape, I mean the individual forms too that contribute towards its general quality, provides me with a kind of stimulus. This object, once I have created it as a sculpture, may harmonize with the landscape that inspired it, in that its form suggests those that I observed.

— B.H. interviewed by Edouard Roditi, Dialogues on Art, London, 1960

No. 7 The Mall studio, Hampstead, 1933. Photo by Paul Laib. The De Laszlo Collection of Paul Laib Negatives at The Courtauld, London.

How is it can we reconcile

a letter with these two profiles?

Or is it three or more we see,

circled almost rapturously,

and not a letter – but a sheet,

folder over, like a warranty?

And where is their resemblance with a cactus plant,

growing like a desert beansprout,

turning on its axis like a strange guitar,

dancing on its torsion like a flute?

It is, without a doubt, the flowerpot

which we decree as their inheritance,

its exultant silhouettes

casting so sweetly, so perfectly

upon the human shapes below.

Is it the ridges of the face

which fit the undulating leaves,

the chin, the nose, which in their still repose

transpose the essence of these shapes?

Or is it the shut, Hellenic mouth,

voluptuous by an eye which seems

aseptic, a pupil like a glass bead,

and perfect, and stolen from a fish?

We do not know – but relish in the slow relay of shapes

and formal aptitudes of plants, and in the way they all translate

the rise and fall of rims and crests of flowers.

We profit from their proximity, as they stand obliquely

so close to one another, exhibiting their brotherhood.

And of what colour we know not,

but black and white,

and not of spots but stripes

and transepts, bisected

like those cut into the canvases

and contours of the face.

It is the play between the silhouettes

and their inevitable backdrop

which produces numerous possibilities, interminable faces.

A flowerpot inspires all such delineations.

[1] Barbara Hepworth: Writings and Conversations, ed. by Sophie Bowness, (London: Tate, 2015), pg. 72

[2] Ben Nicholson: From the Studio (2021). [Exhibition]. Pallant House Gallery, Chichester, UK. 26 June – 24 October 2021.

[3] Barbara Hepworth: Writings and Conversations, pg.36, 80

[4] Barbara Hepworth: Writings and Conversations, pg.46-76

Pietro Bordi is a PhD student at the University of Oxford. His interests include the relationship between literature and the visual arts, particularly in the Renaissance and Modernist periods, and his doctoral thesis focuses on pictorial interpretations of the Divine Comedy in the twentieth century. Passionate about poetry, creative writing as well as ‘ekphrastic’ approaches to image and text, Pietro is College Representative for the Edgar Wind Society for the History of Art at Oxford, and at Balliol organises group visits to London’s National Gallery.

Oxford Micro-Internship

The Digital Media department at The Courtauld was awarded the 2023 Gold Standard Internship Host by Oxford this year.