Polina Ivanova

No documentary or archaeological evidence exists for the site at Sapara before the tenth century. The earliest church at the monastery (the church of Dormition of Virgin) is dated to the 10th century and the church of St Stephanos, near the entrance in the monastery, might have been built in the 11th century but most of the architectural ensemble preserved today is associated with the late thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. In this period, Samtskhe – the region where Sapara is located – was part of the principality of the Jakeli family, a noble household that at one point controlled extensive territories between Borjomi in the east and Erzurum in the west, and continued to rule over Samtskhe until 1578. In 1578 the region became an administrative unit of the Ottoman Empire. The word “principality” seems applicable to Jakelis’ domain because it evokes parallels with the principalities or “beyliks” of medieval Anatolia and places it within the context of the new ephemeral states that emerged in the aftermath of the disintegration of direct Mongol rule. Some of these states continued to exist into the sixteenth century when they were all integrated into the Ottoman Empire.

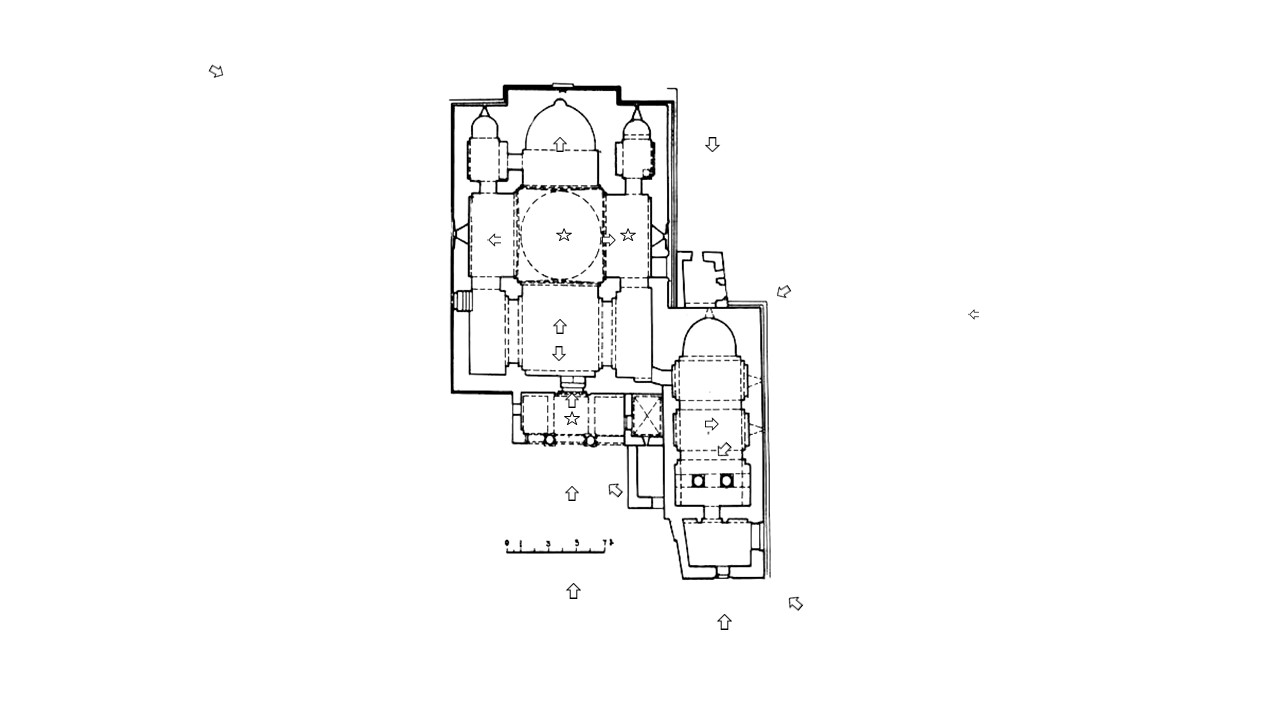

The complex is composed of multiple buildings, including the church of the Dormition of the Virgin (10th century), the church of St Stephanos (11th century), the main church of St Sabbas (late 13th century), the church of St George (15th century) and a bell tower with a burial chapel on the first floor dedicated to St Marine (late 13th or early 14th century).There is also a building identified as the “atabegs’ palace” and several other monastic buildings.

Although we think of monasteries as primarily ecclesiastical institutions and sacred spaces, the example of Sapara vividly reminds us that monasteries could also function as seats of local power and as administrative and economic centres, inhabited not only by monks but also by the laity. The inscription above the donor portraits in St Sabbas reads: “O, father of fathers, the illuminator of the deserts Sabbas, who has shown so many souls a path to God! Be our intercessor before God on behalf of me, atabeg, mandaturt-ukhutses Beka, as well as my sons: Sargis the spasalar of Samtskhe, Kvarkvare, amir-spasalar… Built and decorated this church for all fathers living here, all priests, clerics and lay people.” Several other inscriptions on the walls of the monastery preserve the memory of gifts made to the monastery by other donors and function as legal documents and statements of political alliances.

The iconographic program of the frescos of St Sabbas can be said to follow the Byzantine model. In the main apse we see the Deësis (the figure of Christ enthroned, attended by the Mother of God and St John the Baptist to either side). On the western wall the Last Judgment is depicted, although it is poorly preserved. Like Qintsvisi church, there is a depiction of the tree of Jesse, with some of its figures labelled: David, Solomon, Josaphat, etc.

The dome contains the figure of Christ the Saviour, while the drum hosts the figures of the apostles and the prophets. Above the diaconicon is the Harrowing of Hell and below it the Deposition. On the northern wall, there is a large depiction of the Nativity; on the southern wall the healing of Lazarus, the Resurrection and figures of the saints.

The frescos of St Sabbas undoubtedly are best known for their depiction of the donors, the family of Djakeli atabegs on the south wall of the church. On the painted arch we see St Sabbas (labelled) with four men turned towards him: Sabbas is dressed as a monk and the four figures are dressed in what is identified as the typical garment of the Georgian nobility. One of them holds the model of the church in his hands. Labels above their heads identify them as Atabeg Sargis-Sabba, Beka mandaturt-ukhutsesi with the model of the church, and his sons Sargis spasalar of Samtskhe and a younger man identified by scholars as Kvarkvare, although the label is gone. So what we see here is a portrait of the family, Beka I (1285-1306), with his father – then deceased Sargis I – and his two sons, Sargis II and Kvarkvare.

Sapara monastery is also known for its sculpture, both relief sculpture that decorates the walls of its buildings, and other pieces now preserved in museums. On the exterior western wall of St Sabbas, for example, we find a painting of the mother of God, seated on a throne with the Christ child, flanked by two angels. In the corners of the façade are reliefs of angels “holding up the roof”. The porch contains figures of an eagle with a human face holding a sheep (heraldic?), as well as two doves by a fountain. Inside the church, elaborate stone work and carving decorate the altar, with one figural scene surviving, showing Daniel and the lions. The church of the Dormition formerly contained an impressive altar templon. There were several pieces to it, very finely carved, depicting the Annunciation, Visitation, Presentation, the birth of the Mother of God and the Deësis, among others. They are now preserved in Tbilisi. One model of the church survives – now in the museum of Akhaltsikhe – showing the builder with his tools and an inscription of his name: Parez. He is shown with a halo and from the inscription we know that the church was built by his son. Another model of the church, which was partially visible in a nineteenth century photograph of the interior of the church of the Dormition, is now lost. On the east façade of the Dormition church there is also a small relief showing a man cutting stone and labelled with the name Vache.

Interactive Plan

Image Gallery

Bibliography:

Beriże, V. Arkhitekturnye pamiatniki Samtskhe (Tbilisi, 1970).

Takaishvili, E. “Safarskii monastyr’, ego nadpisi i ostatki stennoi rospisi”, Sbornik materialov dlia opisaniia mesnosteii i plemen Kavkaza, XXXV, 1905, 81-104.

Uvarova, P. ed. Materīaly po arkheologii Kavkaza : Sobrannye ėkspeditsiiami Imperatorskago Moskovskago Arkheologicheskago Obshchestva, IV. (Moskva, 1894), 77-88.