Hadi Safaeipour

Geguti is a Georgian medieval royal palace, now in ruins, at the eponymous village, about seven km south of the city of Kutaisi. The ruins of this palace complex occupy an area of over 2000 m2 along the plains of the Rioni River. The largely secular nature of this complex makes it particularly important given that most of the surviving monuments of medieval Georgia are churches and monasteries. The core of Geguti royal palace was constructed during what is considered to be medieval Georgia’s “golden age”. Although the Georgian court was quite mobile, the establishment of a royal palace of this scale near the kingdom’s second capital which was also a major cultural center can be understood as the desire to establish a more settled, regal court, and royal bureaucracy which, indeed, reached its climax under the Queen Tamar (r. 1184-1213).

Textual sources call the building a palace or “the king’s winter Palace” as well as “The Throne”. One of the earliest records of the Geguti Palace is in Juansheri’s book entitled The Life of Vakhtang Gorgasali. He states that in the eighth century the Duke of Kartili, Archil, said to Leon, Duke of Abkhazetin, that he was going to settle in Geguti castle in Kutisi. Also, the Life of Karti mentions Geguti several times as the place where Georgian kings like David the Builder, and Queen Tamar used to travel into, live, and hunt around occasionally. Geguti palace frequently features in the Georgian annals as a beloved place of rest for the Georgian royalty. In the reign of Tamar, it was the place where her former husband, Prince Yuri Bogolyubsky, was crowned by rebellious nobles during an abortive coup against the queen in 1191.

The earliest surviving depiction of the palace is by Timothy Gabashvili the eighteenth-century Georgian travel writer, diplomat, and cartographer. In his Imereti map drawn in 1737, he depicts the palace and its adjacent church by the river. Considering the placement of the church, the castle, and the river, it seems that the depiction represents the southern façade of the palace. Study of the drawing also reveals that in the 1730s the castle had been in good condition and had not yet been demolished. It is, therefore, an informative document that helps in understanding the architectural and structural features of the building and its dome chamber. Vakhushti Bagrationi, the eighteenth-century Georgian royal prince, geographer, historian, and cartographer of the Kingdom of Kartli surprisingly finds the palace similar to mosques and states: “to the west of Ruini river there is Geguti which is a winter palace. The building looks like Mechiti meaning mosque having many small or large rooms made of hewn stone”. He does not indicate any serious damage or destruction. In the 1830s, however, Dubois de Montpereux visited the castle and reported that the palace had been destroyed. It can be supposed that this demolition was due to a gunpowder explosion during the battle of the Imereti king Solomon II with the Russian army in 1809-1810.

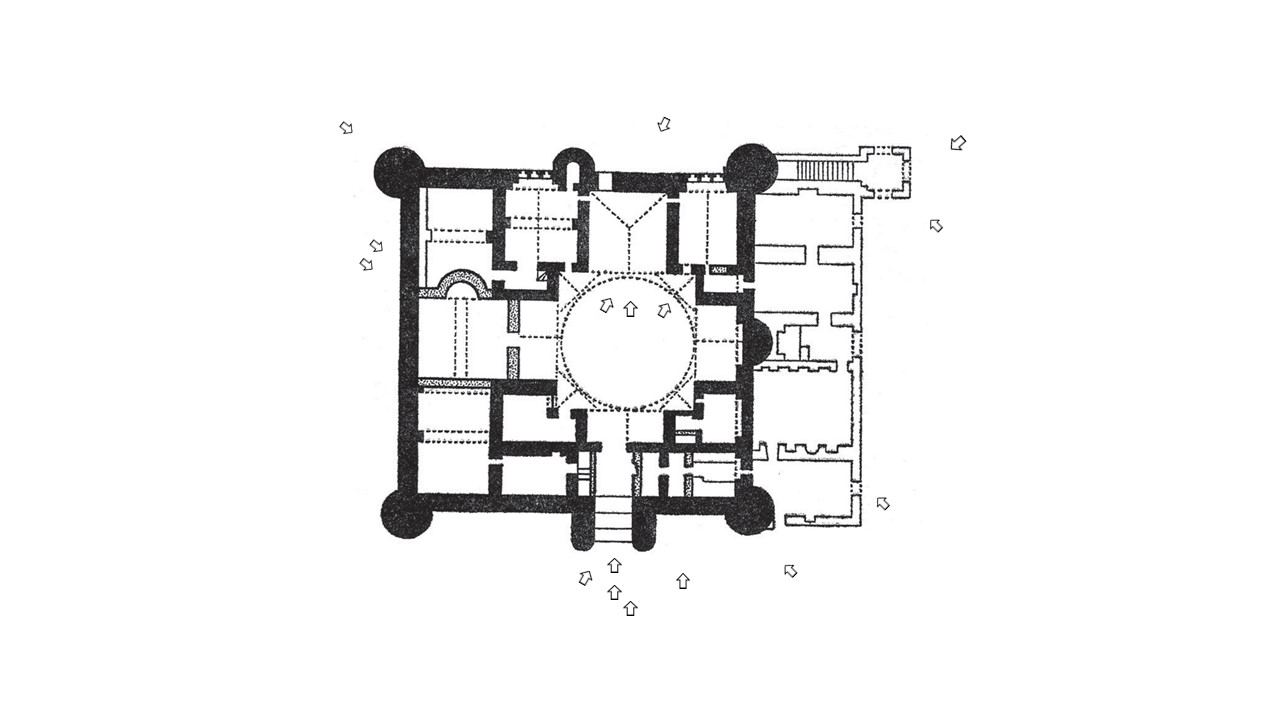

The palace has been shaped based on a cruciform plan enveloped by a fortified rectangular outline. This basic rectangle is relieved by rounded towers that project from the corners and the middle of each side. In front of this structure, there was a pool covered by a tent. The palace was reached through an entrance in the north wall where two pillars embrace the doorway. The vestibule leading into the hall led past a bathhouse to the right and domestic quarters to the left. These rooms form the northern arm of the basic cruciform structure formed around the central domed chamber. The southern arm of the cruciform structure is almost twice as deep as the northern, western, and eastern ones and the throne of the king was placed there. In the southwestern corner of the hall was a bedroom and on the right side, in the southeastern corner two treasuries were placed. On the eastern side there was a hunting lodge which has been used as a kitchen in the later period. The western rooms were originally two stories high. The first floor includes a row of five vaulted rooms. There is an arched doorway in the middle that opens to a small foyer from which another doorway in the north side could be reached. This doorway is framed by a decorated pattern stylistically very close to medieval Seljuk ornamentation. As a result of archaeological and preservation work carried out in the 1950s, it is known now that the walls of Geguti, like royal palaces else-where, were covered with frescoes and the windows had panes of glass.

To reach a better understanding of the chronology of this complex palace, a series of archaeological studies have been carried out. A small-scale archaeological survey of Geguti palace was undertaken in 1937. Later on, extensive fieldwork, between 1953 and 1956, allowed specialists to stratify the principal archaeological layers and reconstruct the architectural form and decoration of the building complex. Accordingly, in his “Der Konigsplast in Geguti”, Wakhtang Tsintsadze suggested three main chronological layers for the palace. The earliest structure includes a plain, one-room building with a large fireplace that dates back to the eighth or ninth century. The fireplace is eight meters wide and is eight meters high, extruding through the second floor. Textual sources indicate that the surrounding lands were utilized as royal hunting fields. It could be assumed, therefore, that this building is the “hunting lodge” mentioned in the chronicles and that it dates back to the fourth and fifth decades of the eighth century when after the Arab conquest King Artschil “leaves Tbilisi, moves toward Geguti palace and Jutaissi city, and settles into this palace.” A principal part of the royal complex was built in the second half of the tenth century as commissioned by King George III (r. 1156-1184). This layer is a four-tier brick building built onto a three-meter high stone plinth, with a spacious, cross-in-square plan surmounted by a dome that is 14 meters in diameter and rests on four squinches. Eventually, the last layer encompasses the additional two-story structure located to the west which is datable to the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. Funded by the National Agency for the Cultural Heritage Preservation of Georgia, archaeological excavations were carried out in September 2015 under the supervision of Roland Isakadze. According to his archeological study 28 new trenches were dug to investigate the stratigraphy of the monument. The recently published report of this fieldwork suggests a more comprehensive chronology based on the identification of eleven stratigraphic layers.

The Palace, both in terms of its design and craftsmanship, has utilized a different and rare architectural vocabulary. Specifically, the use of a cross-in-square domed structure made from brick is a very unique feature in medieval Georgian architecture. These features have been interpreted and explained differently by scholars. Tsintsadze ties this design to the cruciform domed spaces that have been utilized, developed, and replicated in Georgian monastic architecture. He believes this architectural pattern that emerges in Georgian churches and chapels from the fifth century gradually develops through various architectural workshops and reaches its apex in tenth-and-eleventh-century cathedrals. The closest parallel is Bagratti Cathedral in Kutaissi. Tsintsadze therefore connects the design of Geguti Palace to the local inherited architectural tradition of Georgia.

In contrast with Tsintsadze, Beridze explains the palace’s architectural layout as being unique in plan and spatial structure, standing alone among other preserved palaces. He subsequently, indicates that the composition of a domed central hall encompassed by four iwans is a phenomenon that has been effectively utilized in Sasanian architecture. He compares Geguti Palace with Firuzabad palace datable to the early third-century and tries to interpret the design of this Georgian palace in reference to the layout of Sasanian palatial architecture. Similarly, Antony Eastmond considers the design of Geguti Palace as a transmitted concept. He, however, relates the design to the architectural traditions of early-Islamic palaces: “Set on a plain away from the city, the context of the palace is very different from the urban Islamic palaces. But its design suggests that it was expected to function in much the same way. It was a fortified complex that looked inward rather than outwards, and its surviving walls show that its internal layout owned much to Islamic palace design. The plan, therefore, can be a variation of the four-iwan plan that dominated Muslim palatial architecture at this time suggesting that Georgian rulers had adopted the same habit of public display as their Muslim neighbours. The only significant difference is that squinches suggest that the central dome has been covered by a dome, a concession to the local climate.” Overall, the origins of the building’s design remains open for discussion and requires further research.

Interactive Plan

Image Gallery

Bibliography

- Beridze, V., Kartuli Khurotmodzgvrebis Istoria (trans. The History of Georgian Architecture), 2 Vols. (Tbilisi, 2014).

- Eastmond, A. Tamta’s World: The Life and Encounters of a Medieval Noblewoman from the Middle East to Mongolia, (Cambridge, 2017).

- Dubois de Montpereux, Voyage au tour du Caucase, Vol. II, (Paris, 1839).

- Isakadze, R. “Archaeological Material for the Stratigraphy-Chronology of Geguti Palace”, Georgian Antiquities, N20, (Tiblisi, 2017), pp. 46-60.

- Kartlis Tskhovreba (trans.: Life of Kartli (Georgian Cronicles)), Queen Ana’s version/codex, ed.: S. Qaukhchishvili, (Tbilisi, 1942).

- Medici, M. & Ferrari, F. & Kuprashvili, N. & Meliva, T. & Bugadze, N. “CH Digital Documentation and 3D Survey to Foster the European Integration Process: The Case Study of Geguti Palace in Kutaisi, Georgia”, Digital Heritage. Progress in Cultural Heritage: Documentation, Preservation, and Protection, 6th International Conference (EuroMed 2016), 16-21.

- Vakhushti Bagrationi, Agtsera samefosa sakartvelosa (trans. Description of the Kingdom of Georgia), ed.: T. Lomouri and N. Berdzenishvili, (Tbilisi, 1941), pp. 156-157.

- Tsintsadze, W. “Der Konigspalast Geguti (Tavv. LXIII-LXX)”. L’ arte Georgiana Dal IX Al XIV Secolo, Atti del Terzo Simposio Internazionale Sull’Arte Georgiana, (Bari, 14-18 Oct. 1980), 105-112.