Nazenie Garibian

Ateni monastery is situated 12 kilometres south of Gori city, in the valley of the Tana river, one of the branches of the Kura river. Syrian epistolary evidence shows that a church existed in this place even before the seventh century and the excavations of 1969-71 attested the presence of an early Christian basilica. The present Saint Sion Church was built in the seventh century, which is considered the first Golden Age of Caucasian architecture. In this period the main features of church architecture were formed and crystallised. The “classical type” from this period is characterised by the complexity of its structural composition, by the use of entirely cut stone blocks, and by richly carved decoration.

The church represents the so-called “Hripsimé-Jvari” or “Caucasian” type: this is an original layout used both in Armenia and Georgia, at the end of the sixth and first half of the seventh century. St Sion church is clearly inspired by Jvari church in Mtskheta. Even the proportions are copied more or less exactly, and the entrance door is situated on the north side to follow the Jvari arrangement.

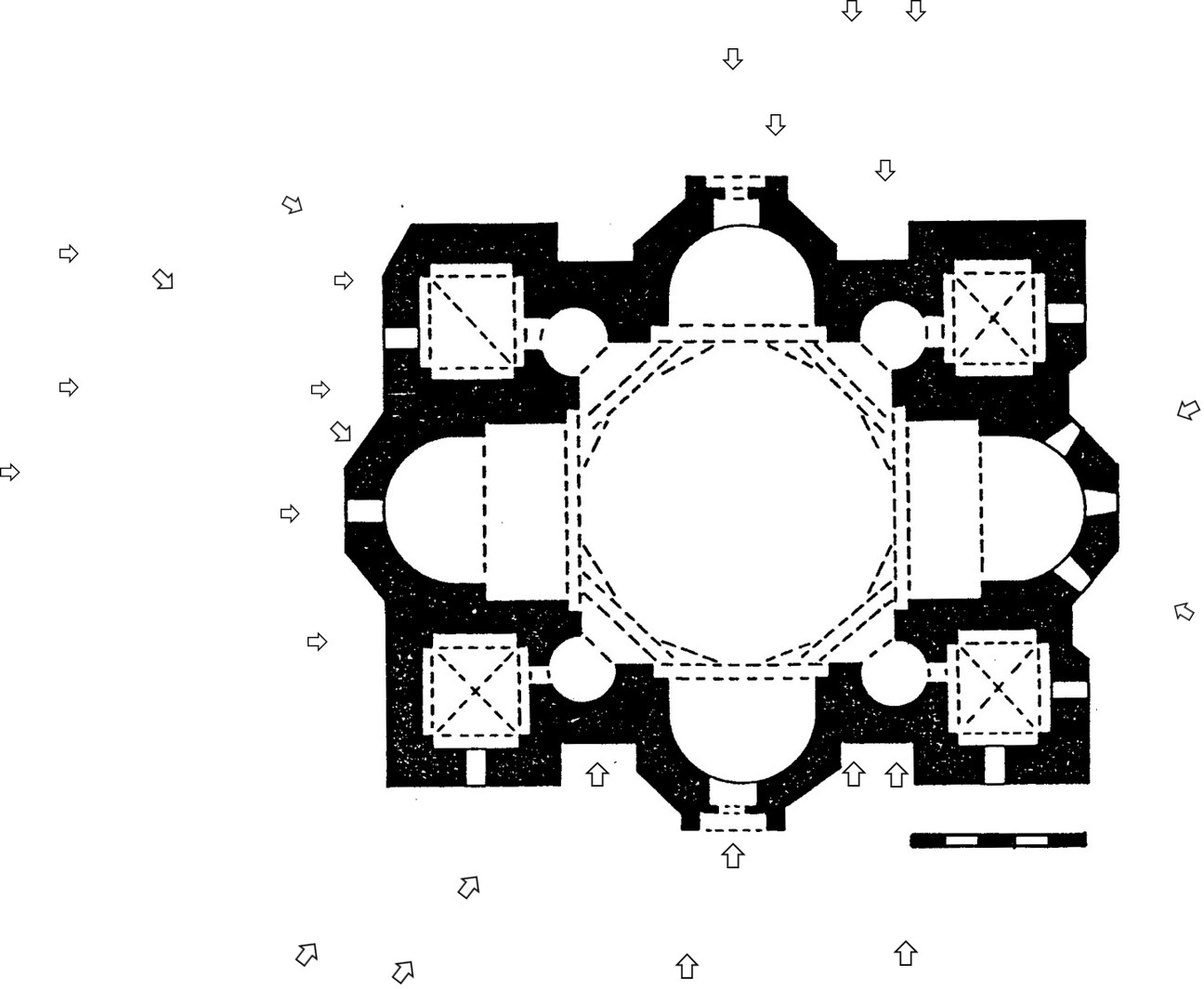

The church is a cross-in-square domed structure, known as a domed tetraconch type, with four apses flanked by four rooms. These chambers are related to the central space by means of four three-quarter cylindrical niches. The interior dimensions of the cathedral are: 24 x 19.22 m. The treatment of the exterior walls articulates the inner layout. The dome rises on an octagonal drum. There is a century-long discussion about the genesis of this type: some consider it a native development; while others try to place it in the wider context of the Byzantine, Syro-Palestinian and Near-Eastern or Iranian traditions. However, we can certainly state that these types of monument have a particular symbolic significance: they were erected as signs of Christianity – the Cross.

There are Armenian and Georgian inscriptions from different periods on the walls of the monument, testifying to the natural interchanges between the two neighbouring Christian countries, which for a long time had a common historical path. The undated Armenian inscription in erkatagir – uncial letters – on the southern façade names the architect – Todosak:

I, Todosak, the builder of this holy church

Other builders with Armenian names are also mentioned in other inscriptions: Aharon, Georg, Grigor Daps.

In the 1940s Giorgi Chubinashvili suggested a seventh century date for this inscription bearing the name of Todosak.Subsequent researchers have considered the inscription as belonging to the great renovation of the monument in the tenth century (982-6). There is also a hypothesis that due to the place of the inscription and its importance, Todosak could be the bishop who was in charge of Ateni Sion and the district.

Another recent publication suggests a more proper dating for the inscription and thus for the foundation of the church, which takes into consideration structural and decorative characteristics, as well as the identification of the donors represented on the eastern façade. According to this theory, these donor images portray erismtavar Nerse I and his son Stepanos, who were active in the last quarter of the 7th century. The church then would have been built in the 680s.

The notable series of reliefs decorating the exterior walls of the church. also clearly imitate the decoration of Jvari church, but they are far from achieving the harmonious system of Jvari. The compositions show an extreme heterogeneity of style and execution. The interchanges between Armenian and Georgian artists are apparent also in the sculptural decoration. However, they should be viewed in the general context of the mixed oriental-hellenistic tradition of Near Eastern, Eastern Mediterranean and Sassanian art in the early Christian period.

Recent studies are inclined to distinguish two stages of execution for these reliefs, the first of which was considered to have been realised by Armenian masters in the 7th century, while the others are attributed to Georgian masters and dated to the period of the great renovation in the 10th century. This renovation is mentioned in an inscription in the western exedra, dated to 980, during the rule of Bagrat III.

On the eastern façade the reliefs represent donor portraits, Samson struggling with the lion (seventh century) and Lucianos, the disciple of David of Gareja. The donor portrait might portray Todosak himself as the Armenian inscription ՏՆ (Տեառն-Tearn), which means “lord”, is applicable also to bishops. On the western façade we find hunting scenes (seventh century), one of which could be again the struggle of Samson with a lion (seventh or tenth century), and the prophet Avacuum (tenth?) The most celebrated relief is that in the lunette of the northern entrance which represents two stags at a fountain, a piece of spolia from the previous basilica on the site dated to the fifth century.

Much more notable are the paintings of the church, which represent a very important stage in medieval Georgian painting and which are not yet well studied. The first painted decoration dates back to the 7th century. It covered only the vaults and arches and was composed of geometrical and ornamental motifs. The relief cross in the dome also comes from this period: it is outlined in red and by motifs which emphasise the lines of the architecture.

The current paintings were realised under the Bagratid rulers in the last quarter of the 11th century, presumably in the 1080s. Due to their content, iconography and high technical level of realisation, they belong to the so-called “metropolitan” or “classical” school of Georgian painting, which continued, to a certain degree, the traditions of Tao-Klarjeti. The style is quite decorative, however: the modelling of the figures is rather smooth but simplified and noses and cheeks are highlighted by white. The overuse of white lines in a very graphic manner is characteristic of Georgian painting, intended to achieve very decorative effects.

The cycles painted on the walls were inspired by the liturgy and in general terms, repeat Byzantine cycles of the Great Feasts, that were elaborated during the 10th century and which were well attested in the 11th. However, there are some interesting deviations from the norm. For example, the cycles are divided into the three apses in order to subordinate the painted program to the architectonic structure of the interior space, which is innovative in terms of its organisation.

In the main apse the figure of the Virgin holding the Christ Child dominates. Two worshipping angels surround her. This motif is similar to the ambitious monuments at Gelati or David Gareja. The Virgin stands above a row of apostles and a row of bishops in frontal poses. On either side are distributed the two parts of a Communion of the Apostles. This was a new theme in Georgia and remained rare until the end of the 12th century.

To this purely Byzantine decoration of the apse was joined a Christ Pantocrator in a medallion on the underside of the arch. The reason for this unusual arrangement is the cross of the dome, which was left in place and painted. The Christ is accompanied by St John the Baptist, Zachariah, David and Aaron as well as by two deacons on the pillars.

The dome rests on corner squinches that are decorated by very rare iconographic scenes: allegorical representations of the rivers of Paradise. These themes should be related to the cross of the dome, for in early Christian art the cross is sometimes raised on a knoll from which the rivers of Paradise flow.

The three other apses each host a well-defined cycle developed in superimposed registers. In the northern apse the cycle represents the Great Feasts but it has been deprived of some scenes that are placed in the cycle of the Virgin in the southern apse, such as the Annunciation, the Annunciation to Joseph, the Nativity and the Assumption. Thus it begins with the Presentation and Baptism in the conch and ends with Ascension and Pentecost.

The southern apse is decorated with a cycle of the Life of Virgin, comprising fourteen scenes. This cycle is known in earlier byzantine traditions, and several churches of the 11th century preserve it in this form. But this is the first time that we see the cycle being based on the apocryphal story in the Protoevangelium of James which narrates the Childhood of Mary and that of Christ, and on the Transitus Mariae (for the Assumption). The only close example of such iconography is in the little Cappadocian church of Sarica Kilise. Among the scenes one is of particular interest because of its Palestinian origins and its rarity in the byzantine tradition: that is “Mary’s testing by the water of denunciation”, where there is the original iconographic detail of the water cup. Another interesting detail is the figure of the apostle Andrew in bishop’s dress in the Assumption scene. From the 9th-10th century, he was considered as the apostle of Kartli. His presence here is due to the local tradition of the Marian cult, which also developed in the 9th and 10th centuries. According to it, the apostles had drawn lots to divide the countries of their mission and the Virgin had also participated. She had drawn Georgia to go to, but sensing her Assumption approaching, she had entrusted her mission to Andrew by giving him her image achieropoites, (not made by human hands), painted by the evangelist Luke.

The western apse represents different scenes from the Last Judgment with a Deësis composition in the conch. It is perhaps the earliest example in Georgia. Besides the saints and prophets there are five donors represented on the northern wall of this apse, one of whom wears byzantine imperial robes. Different tentative identifications have been suggested for them.

In the interior decoration, one can also distinguish two different manners of painting. That of the altar apse is smoother and more artistic, and the style is more sober and monumental. The paintings of the other three apses are characterised by broad brushstrokes and the generalisation of the modelling. Traditional Georgian wall painting is often characterised by ornamental decoration of oriental, Sassanian inspiration: for example, fields of florets and friezes of superimposed leaves derived from crowns or bands of laurel. The paintings, realised at a time when the stylistic methods of the Byzantine school had not yet been crystallised, express an original artistic culture, which became, over the centuries, the classical “Georgian” style.

Interactive Plan

Image Gallery

Bibliography

- T. Virsaladze, Rospisi atenskogo Siona (Tbilisi, 1984)

- G. Abramishvili, ‘La datation des fresques de la cathédrale d’Aténi’, Zograf 14 (1983), 17-21