Sima Meziridou

The Georgian Orthodox monastic complex of Timotesubani is situated in the Borjomi Gorge in the Samtskhe-Javakheti region and consists of a series of structures built between the 11th and 18th century, of which the Church of the Dormition is the largest and artistically most interesting edifice. Constructed during the ‘Golden Age’ of medieval Georgia under Queen Tamar (r. 1184-1213), the Georgian nobleman Shalva of Akhaltsikhe is commemorated as a patron of the church in an inscription.

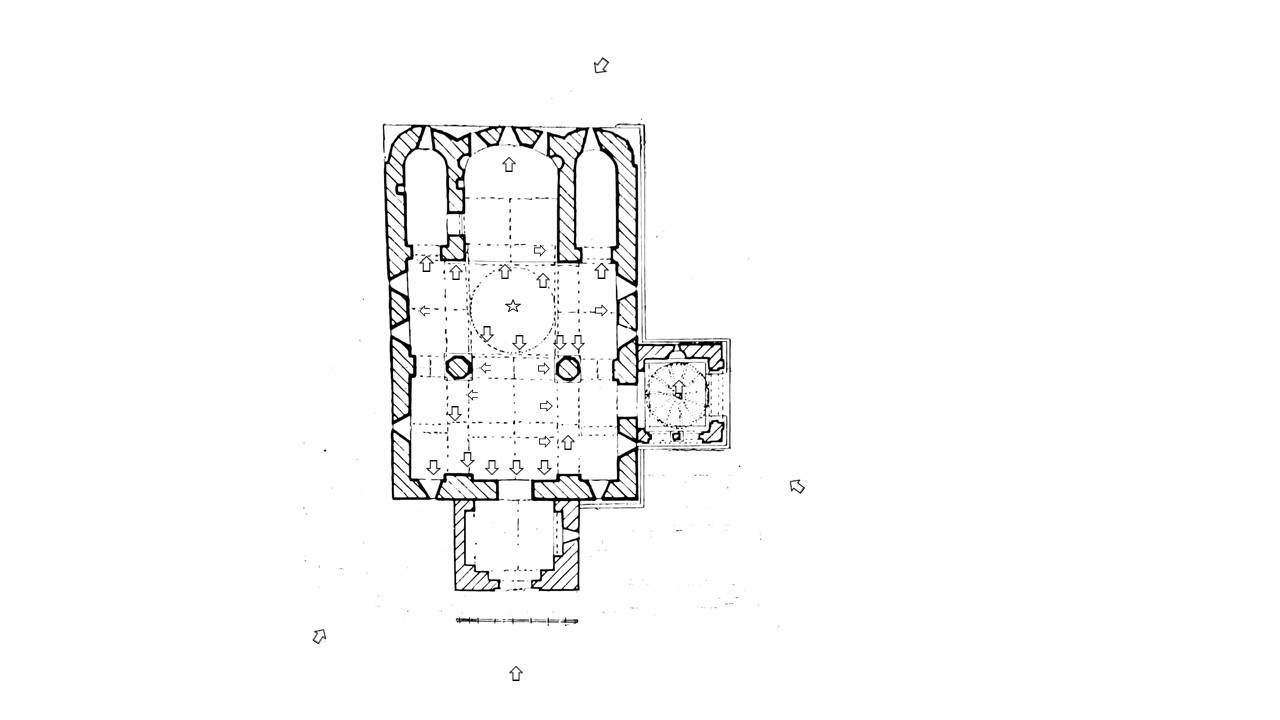

The Church of the Dormition is a domed cross-in-square structure, built of brick with three apses projecting to the east. Its dome rests upon two free standing pillars and projections of the apse walls. Later, two portals were added to the west and the south. The entrance is an arched oblong structure, built of red brick. Above it, presumably the bell tower was built, and on both sides, there were two-storeyed structures that served as the core of the monastic complex. On the site of the monastery there are still ruins of residential and household buildings. On the northern terrace, there is a single-nave church of the Holy Martyr Barbara, and to the north-east of the church there are the remains of a burial vault. The church is 28m high, 19m in width, and 11m in length. On the exterior, the dome is diametrically lined with azure ceramic details.

The iconographic program of the church was painted in the period 1205-1215. There are in total 31 scenes in the iconographic program of Timotesubani, of which 6 are lost. Between 2000-2006, a conservation project preserved the frescoes. Ekatetine Privalova has suggested that the church was dedicated to the Theotokos because of its iconography, which follows trends from the Eastern Christian world, showing Byzantine influence especially. The monument has been dated according to its architectural and iconographic style to the 12th-13th centuries, because its decoration has many similarities with the donor’s portrait of the church in Kintsvisi. The brightness of the colours and the style is similar also to the frescoes at Vardzia, Betania, and Bertubani. The elongation of the figures, the fluidity of their movements, their increased mobility and flexibility, are typical of this period. The frescoes comprise biblical scenes, including scenes of passion of Christ. Inscriptions describing the scenes are typical of the palaeography of this period. It is on this basis also that Privalova suggests a date no later than the 1220s.

The dome of the church, which belongs to a local shape, is decorated on the interior with a depiction of the cross. Below this the scene of the Deisis dominates, surrounded by archangels who are framed by inscriptions mentioning their names. The most important part of the Deisis scene is the clothing of the archangels Gabriel and Raphael, who are dressed in byzantine imperial attire, in red, adorned with pearl shoes and the imperial diadems on their heads.

On the drum of the dome, the figures of twelve prophets, and beneath them the twelve saints and martyrs, are depicted. The prophets, beginning with Moses, are positioned in the order they appear in the bible, and in the hand of Moses there is an inscription with an excerpt from the book of Genesis. The dome composition concludes with the frescoes on the pendentives, featuring decorative elements of the 12th-13th centuries and portraits of the four evangelists in medallions. In the north and south arms, there are scenes from the Life of the Virgin taken from the Protoevangelium of James, including the Annunciation to Anna and the Birth of the Virgin. The Dodekaorton can also be found there – the twelve Great Feasts of the liturgical calendar – including the Annunciation to the Virgin, the Nativity, the Entrance to Jerusalem etc. and the Passion of Christ. These scenes unfold in horizontal bands or strips, without any coherence to the architecture of the church. On the west wall of the church, the Last Judgement is represented, spilling across all three walls.

A very interesting iconographic element, found on the southern wall of the north pilaster, is the depiction of the Mandylion which is now badly damaged. According to Privalova, the Holy Face was painted later, and the Mandylion is the only repainted section of the Timotesubani murals. The Holy Face seems to have replaced the original image of Hades. The latter was represented by an enormous dragon with a naked figure inside it, framed by flames and grotesque faces. The Mandylion was painted directly on the original composition, which was part of the Last Judgement, without applying plaster.

Ekaterine Gedevanishvili suggests that the appearance of the Mandylion after the painting programme was completed might have been the result of a new arrangement of the church space. The monastery had only two entrances on the West and South sides. Later on, two gates were added, the brick gate on the western side and the stone one on the southern part. Perhaps the appearance of the Mandylion replacing a scene from the Last Judgement was connected with this architectural change. Furthermore, the presence of the Holy Face on a scene that related to Hell is reminiscent of the scene of the Descent to Hell. The red halo perhaps gives an association with the Anastasis, since red as a colour has often been used in Resurrection compositions to emphasize the divine nature of Christ (e.g. Vardzia, the Anastasis scene). However, in Timotesubani the focal point of the Last Judgement scene is asecond scene of the Deisis, below which the scene of paradise dominates. In contrast to the Byzantine churches, the Last Judgement scene of Timotesubani does not emphasize the retribution of sin and the torturing of souls, but rather the representation of Paradise. Therefore, Gedevashvili suggests that the later addition of the Holy Face, concealing Hades, was not just a matter of a change in design but that it also created a second image of Paradise.

Privalova argues that Timotesubani is unique on account of its rich and often difficult to interpret decoration, and the unity of the artists and masters who built and decorated the church. Although the decoration is stylistically harmonious and unified, there are individual signatures belonging to each artist and builder who worked on the church.

Interactive Plan

Image Gallery

Bibliography:

- Gedevanishvili E., Encountering the Resurrection, The Holy Face at the Timotesubani murals, Intro al Sacro Volto. Genova, Bisanzio e il Mediterraneo (secoli XI-XIV), a cura di A. Nasetti, C. Bozzo, G. Wolf, Venezia, 2007, pp. 181-186.

- Privalova E., Rospis Timotesubani, Tbilisi, 1980 (in Russian).