Well, my experience at The Courtauld has been fantastic — but it’s flown by so fast! Before I do anything else, I want to thank Dr. Alexandra Gerstein for her support and mentorship through these past few months. The Courtauld Gallery staff in general are an amazing group of people to work for, and it’s been an absolute privilege to have had this opportunity to contribute in my own small way to the work of the museum.

Well, my experience at The Courtauld has been fantastic — but it’s flown by so fast! Before I do anything else, I want to thank Dr. Alexandra Gerstein for her support and mentorship through these past few months. The Courtauld Gallery staff in general are an amazing group of people to work for, and it’s been an absolute privilege to have had this opportunity to contribute in my own small way to the work of the museum.

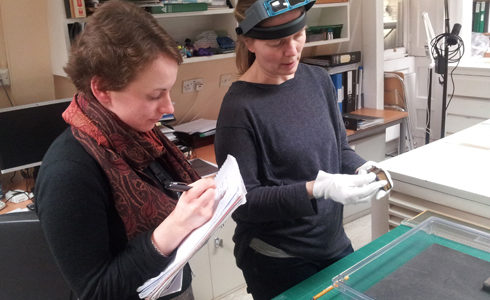

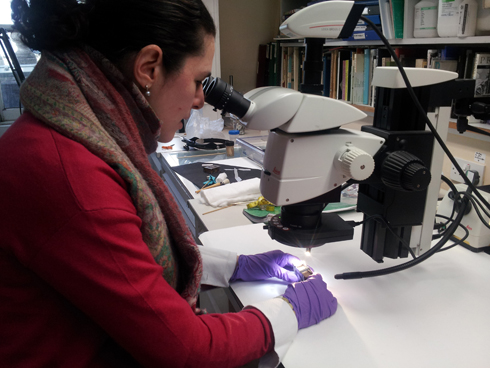

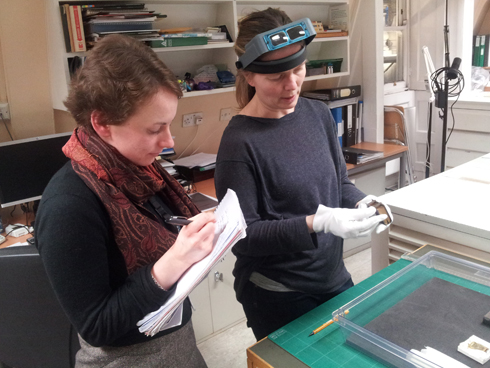

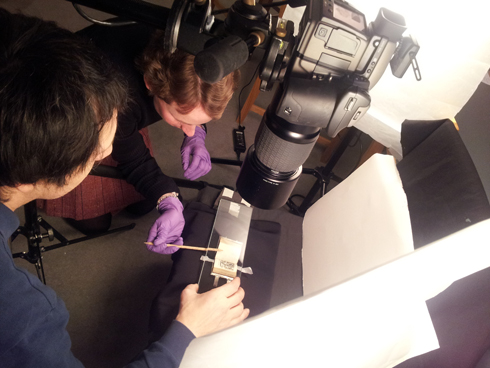

My object – a book shaped pendant with painted-glass panels depicting religious scenes – was installed in the gallery this morning, and it looks great! It was amazing to see everything come together so well at the end, including the beautiful labels and plinth, which I hadn’t really been able to picture until today. We were a little concerned about how such a tiny pendant would look in a large case, but I think we made very good use of the space by printing out high-resolution images of the glass panels and putting them on the plinth. This helps the viewers see the object better and made the space feel warmer.

When I chose this object way back in July, I definitely did not anticipate all the challenges it would bring. It’s an object that doesn’t yield easy answers, that’s a little mysterious—but this is something we theologians love! Even now, after five months of researching, consulting experts, and reflecting on the pendant, it still keeps its secrets.

Just a final comment on the research process — one of the highlights of my experience has been speaking with and learning from experts in the fields of art history and curatorial research. Toward the beginning of my research, I had the opportunity to meet with Dr Ayla Lepine, Lecturer in Art History at the University of Essex and an expert in Victorian aesthetics, who actually helped me select my object. I was also very pleased to meet with Kirstin Kennedy, a curator of metalwork at the Victoria and Albert Museum, on several occasions; her insight on the object helped me probe much more deeply into the questions the object raises. Finally, I was “serendipitously” (thank you, Google) able to track down a doctoral researcher from the University of Giessen in Germany who is currently studying book-shaped pendants from the Renaissance. This was an amazing coincidence, and Romina was kind enough to fly to London and share her expertise with us. Meeting these generous scholars has been a delight, and one of the experiences I will treasure from my internship is having been in a truly collaborative educational environment. In my experience, university academia can sometimes feel resistant to this kind of collaboration, and it was refreshing to be involved in a project in which various perspectives were so vividly able to cross-fertilize and enrich my own study.

Just a final comment on the research process — one of the highlights of my experience has been speaking with and learning from experts in the fields of art history and curatorial research. Toward the beginning of my research, I had the opportunity to meet with Dr Ayla Lepine, Lecturer in Art History at the University of Essex and an expert in Victorian aesthetics, who actually helped me select my object. I was also very pleased to meet with Kirstin Kennedy, a curator of metalwork at the Victoria and Albert Museum, on several occasions; her insight on the object helped me probe much more deeply into the questions the object raises. Finally, I was “serendipitously” (thank you, Google) able to track down a doctoral researcher from the University of Giessen in Germany who is currently studying book-shaped pendants from the Renaissance. This was an amazing coincidence, and Romina was kind enough to fly to London and share her expertise with us. Meeting these generous scholars has been a delight, and one of the experiences I will treasure from my internship is having been in a truly collaborative educational environment. In my experience, university academia can sometimes feel resistant to this kind of collaboration, and it was refreshing to be involved in a project in which various perspectives were so vividly able to cross-fertilize and enrich my own study.

This blog post was originally published on The Courtauld Gallery Blog.

View the original blog post

Back to A 17th Century Pendant