A Venetian Opalescent Glass Bowl

The materiality of opalescent glass and its resonance with bioluminescent organisms

Designer Marisa Leñero explores the visual nuances of an 18th-century Venetian opalescent glass bowl. She considers the echoes of bioluminescent sea creatures in its design and looks at the impact of lighting conditions on the way in which we see this magnificent object. Work on this project was carried out during her Masters in Global Innovation Design, a joint programme between the Royal College of Art and Imperial College, London.

A Thirst for Innovation: Looking at Technique

Venetians have excelled in the production of exquisite glassware for many centuries. The glass-making industry, situated on the Venetian island of Murano, is thought to have reached its peak in the quality and innovation of its production between 1520–40, when its craftsmen found the formula to make glass perfectly colourless. This glass was known as cristallo and became the hallmark of Venetian prestige and technical skill in glass-making. Having perfected colourless transparency, Venetian glass-makers continued to push their technical boundaries in other directions. They were thirsty for re-invention.

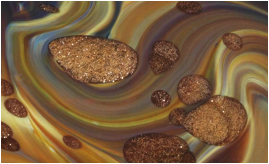

In the late 17th and 18th centuries, glass-makers developed new materials in the service of stunning visual effects. They sought to make coloured glass that could imitate precious stones and minerals such as chalcedony, which applies to another Venetian bowl in The Courtauld’s collection, seen on the left. Craftsmen were highly skilled in obtaining complex forms through manipulating the molten glass with specialised tools such as pincers, by blowing it into moulds, or by combining various techniques.

The Courtauld’s exquisite blue glass bowl bears testimony to the high standards of Venetian glass-makers during this period. It recalls opal, a mineraloid or non-crystalline mineral with different material densities ranging from semi-transparent to opaque. Opal can be either iridescent or opalescent (milky in appearance). Early in the 17th century, the stone was known by the Italian word for sunflower — girasol — in reference to its changing qualities under various lighting conditions.

When light passes through the milky white-bluish tones of this opalescent glass, its hues vary from oranges to fiery reddish colours, creating a visual effect which demonstrates the superb skills of the craftsmen.

The light ribbing on the bowl is a strong indicator that this piece was first blown into a mould, with the handles being added later. The crests on the handles were made by pinching the molten glass with the help of pincers.

Emulation of Nature: Glassy Echoes of the Sea

…all the effects of glass are marvelous (sic). Considering its brief and short life, it cannot and should not be given too much love, and it must be used and kept in mind as an example of the life of man and of the things of the world which, though beautiful, are transitory and frail.

The Pirotechnia of Vannoccio Biringuccio (Venice, 1540)

This delicate and thin Venetian glass bowl is striking in its evocation of natural forms. Several of its features have an affinity with the underwater world and maritime creatures. On a simple visual level, the pincered handles look like the back of two transparent hippocampi or seahorses holding the bowl together.

On a subtler level, the bowl itself has a similarities in appearance to jellyfishes.

Credits: Cornell Collection of Blaschka Invertebrate Models, Cornell University, NY

Photographer: Gary Hodges

The rounded shape and ribs of the object seem to conjure in some way the soft bodies of the jellyfishes and the gelatinous umbrella particular to those organisms. Under certain natural light conditions, the bowl looks like the Aequorea victoria, or crystal jellyfish, which is characterised by its translucency and compactness. The tentacles of these creatures are inside the umbrella bell, making them different from the jellyfishes whose limbs float below their bodies.

Jellyfishes also caught the attention of 19th-century glass artists Leopold and Rudolf Blaschka, who were widely admired in their time for their masterful skills in the reproduction of flora and fauna. Although aesthetically and functionally rather different, the Blaschka duo’s creations could be compared to this delicate Venetian glass bowl in their maritime inspiration. The sea could act as a source of inspiration — whether literal or more subtle — to glass-makers through the centuries.

Bioluminescence in Jellyfish: Informing the Display

This glass bowl’s peculiarity of changing colour under certain light conditions resonates with the bioluminescent characteristic that some jellyfishes have — a unique ability to glow by themselves. This feature is generally produced by the mixture of two proteins: luciferin and luciferase. However, the Aequorea victoria jellyfish glows due to a specific protein called photoprotein, a type of enzyme which produces a brief flash instead of the steady light generated by the luciferase. A similar sparkle effect can be achieved during the first seconds whilst this opalescent bowl is illuminated.

Communicating the richness of this object and the secrets that it holds poses a number of display challenges that are of particular importance from a designer’s perspective.

While illuminating the object from different angles and trying to elicit the fiery colours in it, suddenly the glass bowl seemed alive, like it was dancing. It was as though the movement of the light across its surface had filled it with life and evoked the rhythmic flow of a jellyfish swimming in the deep waters of the sea.

I tried to convey this by including a fading effect in the light that illuminates the bowl while on display.

Illuminating two glass objects from an angle. Melisa Leñero and Matthew Thompson.

In discussing the display, I became inspired by the contrast that must arise between the glow of jellyfishes and the pitch black of the dark ocean. I replicated this juxtaposition of light and dark through choosing a jet-black Perspex for the base of the display case and inserting a small light source directly under the bowl. On this mysterious-looking surface, which resembles the deep black waters of the sea, the delicate bowl seems to float and gently pulsate with light.

The triangles in the case each have their own design purposes. One is painted black and two others are a cut-out to reveal the bowl. The painted trompe l’oeil triangle materialises the negative space of the beam of light that a lamp would produce if it were illuminating the object. The cut-out triangles reveal the opalescent glass bowl in a very stark fashion, almost indicating there is nothing else to admire but the glass bowl.

The overall arrangement of the display is to convey the skeuomorphism of the glass bowl, in other words, the resemblance to another object embedded in it. On the one hand, this piece is made of delicate glass and functions as a vessel. On the other, the bowl’s appearance associates it with a gelatinous sea creature that has the particular characteristic of illuminating itself.