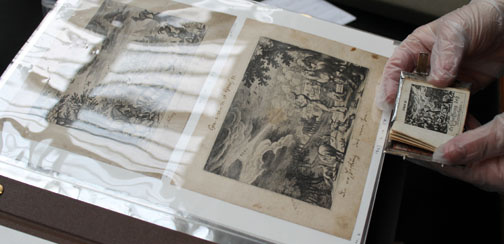

This pair of German miniature picture Bibles entitled Dess Alten Testaments Mittler: Dess Neuen Testaments Mittler, was produced by two sisters from Augsburg in the late seventeenth century. They were most likely designed for use in private devotion.

Johanna Christina (or Christiana) Küsel (born 1665, active until about 1700) was responsible for the designs and Maria Magdalena (active about 1688 – 1702), was the engraver. Whereas it is thought most seventeenth century ‘thumb’ Bibles were destined for children, the Küsels’ Bible, with its complex and intricate engravings, is likely to have been intended as a portable object for private contemplation rather than children’s education.

Family Purpose

The books were printed without place or date, but we know the sisters belonged to a family of talented printmakers in Augsburg, and were active during the second half of the seventeenth century. The title page mentions their name as the designers and engravers, but with the alternative spelling of ‘Kuslin’ instead of ‘Küsel’. The family workshop probably produced images as illustrations in numerous shapes and forms, adapting and reusing compositions for various purposes and formats. The sisters’ father was the engraver Melchior Küsel and their grandfather was Matthaeus Merian, whose most famous engravings were for a history of the Bible published in Frankfurt in 1625, known as the Icones Biblicae. Merian’s engravings dealt in depth with the religious concepts of the time by emphasising the individual’s relationship to God over exterior acts of public worship. The purpose of the Icones, Merian stated in his printed dedication, was ‘not only to amuse, but also, and this pointedly, to enlighten and encourage one’s soul, to trigger reflection of the history involved’. Merian called the Icones ‘a small, comfortable edition of the Holy Bible in hopes that it be not only a feast for the eyes but also be moving and maybe put some fear of God into those that need it’. The Küsel sisters had first-hand knowledge of their grandfather’s prints, and thus based their engravings on his compositions, adapting them to suit the scale and purpose of their miniature books. The dimensions of the miniature image area are 33 x 35 mm, at least 1/6th the size of Merian’s prints for the Icones Biblicae, which measure 102 x 146 mm inside the platemark.

Reformation and Private Devotion in Augsburg

An increasing emphasis on private devotion and personal piety in German speaking countries during the seventeenth century created an environment favourable to the production of engraved biblical cycles and also opened up the manuscript market for them. As stress was laid on individual piety as a way of drawing Christians closer to God, so the demands for books and images to use in private devotion grew across the social spectrum.

Artists, firmly situated in the middle classes in Augsburg, had to work with the religious constraints imposed by the Reformation. The theological context of the miniature picture Bibles stems from Luther’s teaching, still prevalent in Augsburg in the late seventeenth century, more than one hundred years after his death in 1546.

Miniature personal prayer books were the accoutrements of fashionable circles in Catholic countries as well, as for example seen in this splendid portrait drawing by Peter Paul Rubens of his young wife Helena Fourment in The Courtauld’s collection. Dressed sumptuously, as though about to step out, Helena Fourment is shown here holding what appears to be a miniature prayer book in her hand.

In Protestant personal devotion, viewers were encouraged to use the printed image within the context of ‘self-reformation’. The image and text together formed a meditative programme that expressed sacred truths, which the reader was invited to meditate upon for the purpose of conforming the soul to the Divine will. The image was therefore an aid in gauging the soul’s closeness or distance from the Divine and a prompt for furthering that relationship.

Back to German Miniature Picture Bibles