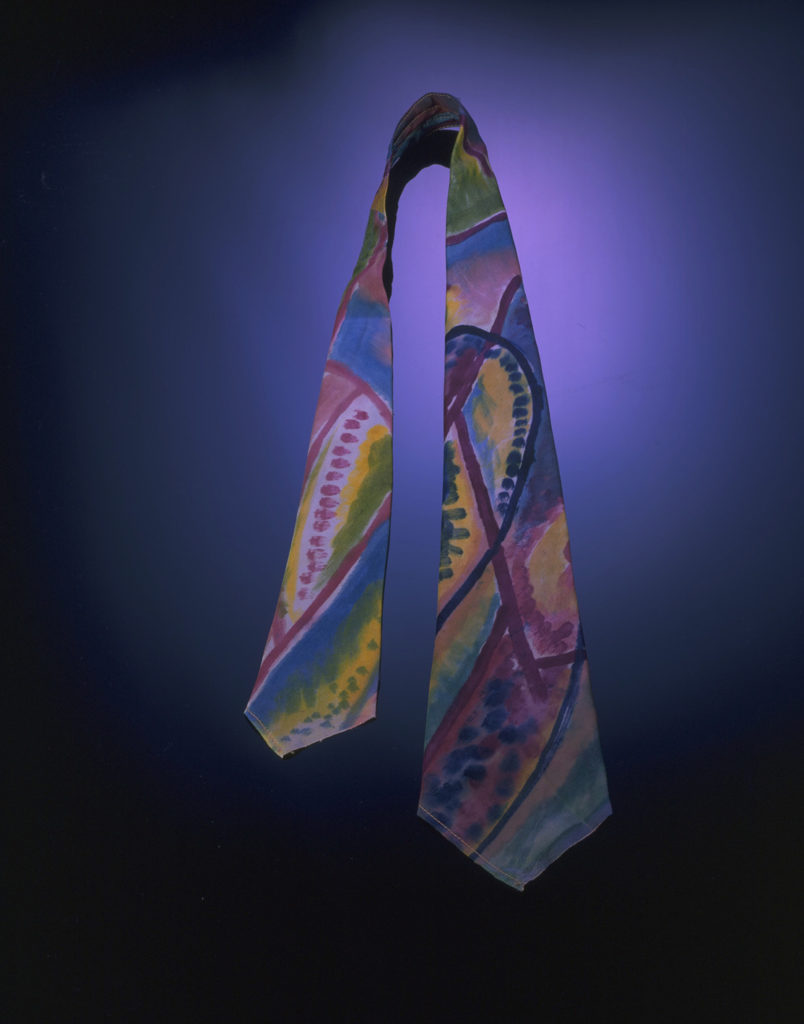

Silk Fragment

by Jock Turnbull in the Omega Workshops

This hand-painted silk encapsulates a moment of artistic response to a long period of industrial change in Britain. Created within the Omega Workshops, this piece blends the realms of fine art and wearable clothing with an aesthetic that stood against the machine-made production of the time.

The hand-painted silk is on display at The Science Museum in London from May – September 2021, as part of the Illuminating Objects partnership while The Courtauld Gallery is temporarily closed for a major refurbishment programme. The connection to The Science Museum provides an opportunity to focus on the scientific ideas and techniques embodied in this painted silk fragment. This webpage has been researched and written by Sophie-Nicole Dodds, a postgraduate student in the Masters in Design: Expanded Practice at Goldsmiths. Having previously trained in Bespoke Tailoring at London College of Fashion, Sophie looks at construction and making as part of design. She comes to the Illuminating Objects Internship in a different context from previous students due to the pandemic. While she has selected her object entirely through a computer screen, she has been utilising her design background to examine these objects creatively.

On this page you can find:

Art Practice as Resistance

Expressing my artistic intentions from a design perspective

A Vision in Design, Roger Fry

Roger Fry’s views on arts and crafts in relation to science

Experimental Silk, Jock Turnbull

Unpicking the maker of the fragment

Dressing at the Omega

Omega Artist Winifred Gill’s relationship to fashion

Art Practice as Resistance

This delicate, hand– painted silk ‘fragment’ was created within the Omega Workshops in 1914 by Jock Turnbull (born 1890, active 1920s). Opened on the cusp of the First World War, the Omega Workshops Ltd. was an art and design studio set up by artist and critic Roger Fry (1866-1934). In researching objects from The Courtauld’s collection, I was drawn towards pieces that could be seen as fragments, or overlooked pieces, initially with a focus on making and the ways in which design narratives can be obscured. In these pages, I pursue three areas of interest around Turnbull’s silk fragment, focusing on three extraordinary figures in its story.

I start with Roger Fry and his thoughts on arts and craft in relation to science, exploring the significance of this to the materials and methods used in the silk piece. Second, I turn to the little-known history of Jock Turnbull to deconstruct how the piece was created. Finally, I finish with Winifred Gill (1891-1981), the owner of the silk fragment, which she called a scarf, and her relation to fashion both within the Omega and in the context of today’s world. Throughout these three sections are interwoven my own visual responses to the silk fragment and its stories. I use my perspective as a designer to connect with and understand this fascinating textile.

A Vision in Design, Roger Fry

Fry’s intention was to create a working studio, which developed domestic interior designs by young artists and craftspeople with specialisms in textiles, ceramics, furniture, and fashion. To showcase the quality of the products rather than the name of the maker, the objects produced were not signed by the artist but with Ω – Omega. In physics, the Greek letter Ω represents electrical resistance, the ohm. It has been suggested recently that Fry interpreted the letter as a type of radical transformation which led him to choose the Omega name (Arthur S. Marks, A sign and a shop sign: The Ω and Roger Fry’s Omega Workshops, in British Art Journal P18, Spring/Summer 2012). The Omega Workshops promoted a specific aesthetic and working practice. Both of these were a form of protest against current ideals: blending the realms of fine art and wearable fashions against the machine-made production which had become prominent by the 1910s. Fry sought to encourage ‘the directly expressive quality of the artist’s handling’ instead of the ‘deadness of mechanical reproduction’ (Beyond Bloomsbury, Teaching Resource, 2009).

Examples of hand painted designs on paper for the Omega Workshops, as seen here for a silk stole and rug. Use the slider to compare the colours of each design in relation to our silk fragment.

Design with confronted peacocks (recto) – 1913-14, Attributed to Roger Eliot Fry (1866-1934) The Courtauld, London (Samuel Courtauld Trust) © The Courtauld © Estate of Duncan Grant. All rights reserved, DACS 2021. © Estate of Vanessa Bell. All rights reserved, DACS 2021© The Courtauld

Initially studying Natural Sciences at Cambridge, Fry decided to leave this behind and pursue his overwhelming interest in the fine arts. In his piece An Essay in Aesthetics (1909) he brought together five emotional elements of design and discussed how close the aims of art and science could be seen. He claimed ‘that the motives of science are emotional, many of its processes are purely intellectual, that is to say, mechanical.’ and that ‘They could be performed by a perfectly non-sentient, emotionless brain, whereas at no point in the process of art can we drop feeling.’ By comparing art and science from a psychological point of view he links their processes by saying that even when art is mechanical like science, there’s a personal element we cannot remove from the creation. In 1913, Britain was coming towards the end of a technological revolution in which innovative manufacturing methods and the establishment of the machine tool industry fundamentally changed production of domestic goods.

Studying the particular production of the silk piece, we see that it is a typical dressmaker’s silk of the time, available at shops such as Liberty’s, which has then been customised and hand-made. All nine colours have been applied by hand using a brush. The piece of cloth has a selvedge either side – an edge produced on woven fabric during the weaving process that prevents it from unravelling. One of the long sides is left raw while the other is machine stitched, suggesting it is a fragment torn away to be experimented upon. This is not a mass produced piece, evoking Fry’s ethos of the Omega Workshops. However, the dyes raise questions. Although we cannot be sure, these dyes may be synthetic. If they are, that would show how The Omega’s commitment to artistic production worked together with a relaxed attitude towards fabrication.

Natural dyes have been used for centuries to dye material, but in 1856 the first commercially successful synthetic dye Mauveine was introduced and within decades synthetic dyes were available in almost any shade. The synthetic dyes were produced with an experimental aniline, a colourless aromatic oil derived from coal tar which was a common waste product of the 19th Century. Aniline was a starting material for industrial chemical products like synthetic dyes, however the problem with these dyes was that they were liable to fade. William Morris (1834-1896), who was the leader of the 19th Century movement known as the Arts and Crafts, championed the hand over the machine, and accused the artificial aniline dyes of ‘destroying all beauty’ in the art and process of dying. Fast dyes called ‘Sundour’ were made by chemist James Morton (1867-1943). They resolved the issue of fading and were sold to high-end fashion houses including the English company Burberry. James Morton’s dyes and the process behind it would be classed as environmentally harmful by contemporary standards. These dyes can first be seen in an advertisement for Burberry in 1913, around the same time as the foundation of the Omega Workshop.

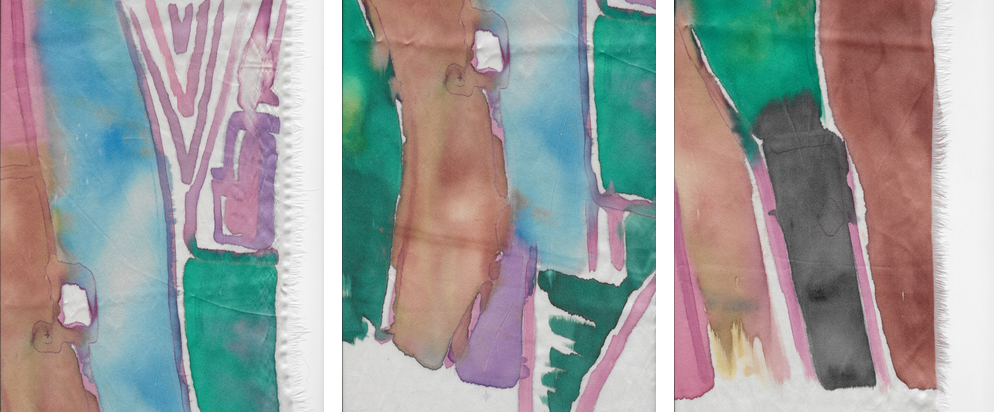

McQueens Illuminating Objects Intern Sophie-Nicole Dodds tests painting synthetic dyes, watercolour and egg tempera onto pieces of sand-washed silk cloth.

It is not known what dyes were used for painting in the Omega Workshops, and even if they were synthetic dyes it is doubtful that they would have realised the harm they were doing to the environment.

Close up scans of painting synthetic dyes onto sand-washed silk by Sophie-Nicole Dodds

Fry’s concerns resonate for me in relation to contemporary environmental critiques of the fashion industry. The textile industry continues to use chemicals that are harmful to the environment, as well as being the second largest polluter of water resulting from large-scale textile dyeing and treatment procedures. Fast-fashion is a major contributor to this pollution. If Roger Fry were alive today, we can imagine that he would be leading the way for sustainability within design. ‘Fast Fashion’ would most certainly not be his business model, and we can be sure he would have focused instead on a slow, enduring and artistically free crafting process.

Experimental Silk, Jock Turnbull

Little is known about John Armstrong Turnbull, known as Jock, and his time at the Omega Workshops but elements can be pieced together from a number of sources. Firstly, the silk came into The Courtauld’s collection in 1959, donated by the craftswoman and social reformer Winifred Gill, who described it as a ‘scarf’. Gill played a key role in running The Omega Workshops. In the 1960s she set out all her memories about that period in a series of letters she wrote to fellow member of the Omega Workshops, the Bloomsbury Group painter Duncan Grant. In one letter, Gill mentions Turnbull and that she could not ‘remember where he came from or when he joined us’.

Listen here for Winifred Gill’s niece reading out her letter to Grant

It is thought that Turnbull may have been a member of the Vorticist Group X, a British avant-garde Futurist movement formed by the artist Wyndham Lewis (1882-1957) in 1920. William Roberts, a fellow member of Group X, in his piece Some Early Abstract and Cubist Work 1913–1920 (1957) wrote ‘Airman Turnbull vanished with the same jet-like speed with which he had flown in upon us’. Three paintings by Turnbull are today in the Canadian War Museum, and they interestingly evoke the abstract nature of this painted silk. The paintings depict war planes high above a cityscape scene in a haze of washed-out and muted tones. They were commissioned by Lord Beaverbrook, who created the Canadian War Memorials Fund, and were later donated to the Museum.

Turnbull’s expressive silk piece has a playful design that gives us a strong visual sense of Roger Fry’s aesthetics. The colours bleed into one another, creating a visually fluid and arresting object. Unfinished, it fires curiosity and imagination. As it is silk, there is a slight shine to it that ripples in the light and creates a translucent effect. You might see the fields and rivers of rural England within its abstract forms, combining ideas of the natural and changing technological charms of early 20th Century Britain.

In his Essay in Aesthetics, 1909, Fry described a Chinese roll of silk, which upon reading I found so evocative of Jock Turnbull’s design, that it was as though he was describing this piece:

Sometimes a landscape is painted upon a roll of silk so long that we can only look at it in successive segments. As we unroll it at one end and roll it up at the other we traverse wide stretches of country, tracing, perhaps, all the vicissitudes of a river from its source to the sea, and yet, when this is well done, we have received a very keen impression of pictorial unity.

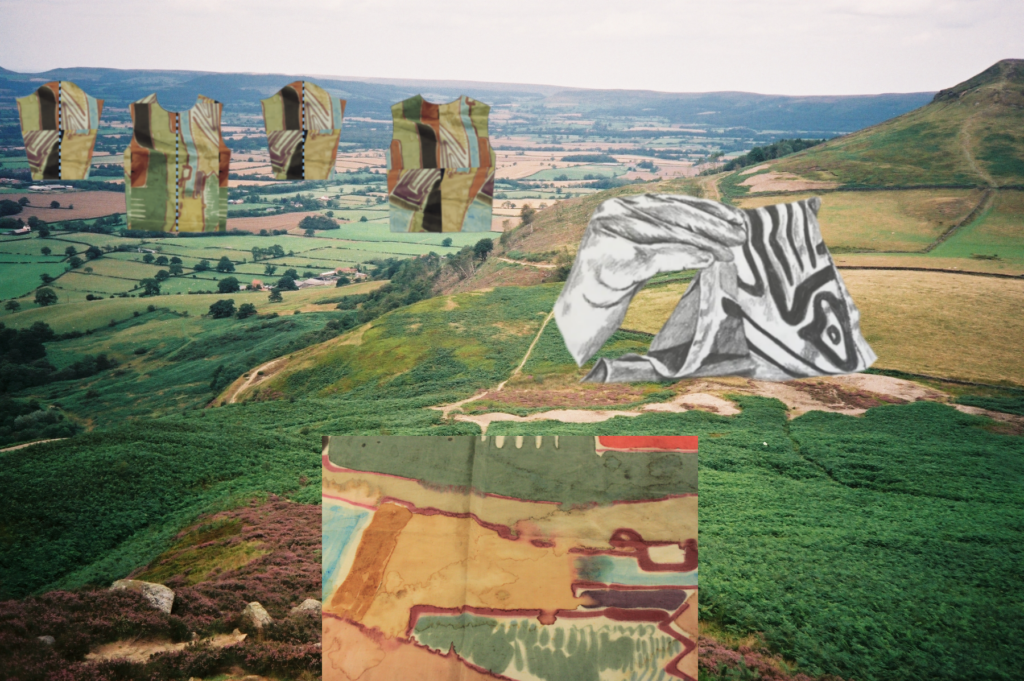

In this visual response I have created a collage using a backdrop of a film photo I took in Yorkshire in August 2019. It is layered with a drawing of a gloved hand holding the silk, from the first time I saw the piece through a video call, and a cropped section of the silk that I felt evoked the colours of the purple heather, yellowing grass, and dark green shrubs as well as reflecting the patterns and shapes of the fields. There is also a flat pattern CAD drawing of the scarf ready to be cut to be made into a tunic top, working in Omega’s way of blurring decorative arts and dress.

Upon closer inspection of the stitching with Textile Conservator Louise Squire, we came to the conclusion that the hem on the fragment seems to be in three parts. Someone has pulled the weft (horizontal) threads to make small holes ready for a technique called drawn thread work, which is what is often used on linen sheets. On the one side there is a perfect example by someone who is experienced with drawn thread work with no tacking (a quick large stitch to hold something in place intended to be removed). In the middle we have an attempted version of the drawn thread work presumably by someone of lesser skill, as it is not as neat. In the third section the pulled weft threads have stopped and so has the attempted drawn thread work, where only the rough tacking remains, finishing the hem in a haphazard way. This suggests someone sewed the first section to show how it was done, then the pupil never managed to finish it. As this textile is an Omega object, technique wasn’t what they were most interested in. From the outsider’s view, we’d see it as a test piece, but in a looser sense Omega didn’t really have test pieces it was just how they worked: something could start out a test piece and then be sold and used or, like this piece, remain unsold in the workshops. Click the wider image zoom link in the top right hand of the image to see these sections more closely.

The piece reminds me of the Japanese aesthetic of Wabi-Sabi, where beauty is seen in the imperfect, impermanent and incomplete. Likewise, another Japanese term Mingei, coined by Japanese art critic Yanagi Sōetsu (1889-1961) and meaning “ordinary people’s crafts” proposes that beauty is to be found in ordinary everyday objects made by unknown craftsmen, as opposed to higher forms of art created by named artists. Drawing on this philosophy and displaying this textile at the Science Museum not only does it give a voice to the relatively unknown artist, Jock Turnbull, but also gives hope to unknown objects, whose stories can be seen in a new light. These ideas link us to today’s ‘Makers Movement’ by honouring craftsmen who come from all walks of life with different skill sets and interests. The artisan spirit of learning through doing is as much a reaction to the de-valuing of making today, particularly as seen in fast-fashion, as Fry’s Omega Workshops was to the mass-production of the 1910s.

Dressing at the Omega, Winifred Gill

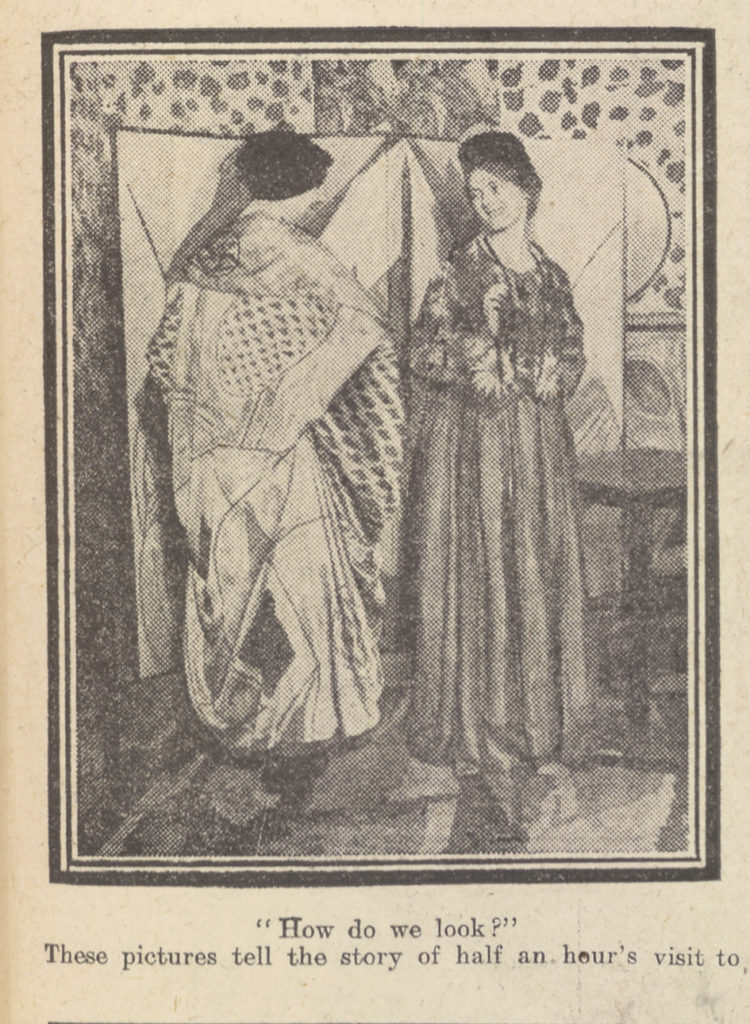

Textiles are part of our everyday lives, they are familiar but powerful objects. For the Omega Workshops they surrounded the familiar confines of their living and working. In 1914 the painter Vanessa Bell (1979-1961) started a dress department within the Omega Workshops. Winifred Gill describes in her letters to Duncan Grant in 1966 how she dressed during the day, working in ‘overalls… literally stained with paint and dye’. From various people’s accounts at the time, we know how ‘makeshift’ the dress aesthetic was. Gill reminisced about the importance of dyes and hand painting. They produced hand-painted silk dresses, evening cloaks, opera bags, fans, silk ties, parasols and much more to break the boundaries between dress, painting, sculpture and printing. Gill describes how she ‘took a spare length of plain material used as lining for curtains, folding it round me with good overlap and safety- pinned it to my waist, over this I wore a tunic of omega linen’, and elsewhere she describes wearing a striped skirt that was ‘simply made up of a length of plain material and tied round the waist with a piece of tape.’ We can therefore easily imagine Gill acquiring this off-cut hand-painted experiment that Turnbull had done in the studio and deciding to wrap it around her neck as a scarf.

Turning to our silk fragment, it is difficult to tell if the material has been sized – where a substance is applied to a textile to change the absorption and wear characteristics of the material. In another letter to Grant, Gill wrote of the Workshops’ version of this, “I would say that we ‘painted’ cushion covers, scarves and lampshades in dyes on silk’, which were then prepared by ‘being brushed over by some paste or starch mixture brewed by Miles the caretaker.. This treatment rendered the silk as safe to paint on as paper’. This ‘treatment’ or ‘fixture’ is not explained in detail, nor are the actual dyes. Nonetheless, we can read a story in the process of the piece from one side to the other: a deliberate pattern in one area, a happy accident in another, an attempted reproduction of an existing Omega pattern in one more. It is very iterative in how it has been made, there are striking parts and more subdued parts. There are places where Turnbull has been specific in his line drawing, and others where he has been very carefree and the colour has leached. Did he leave and come back to the work? There is an unpredictability in how it was made, in Turnbull’s design, as well as in the reactions of the dye with the materials. It seems this fragment was a rapid, experimental piece, not a labour of love.

In this visual response I have created another collage using a backdrop of a film photo I took in Hastings in December 2020. It features a different cropped section of the silk that I felt evoked the same shade as the blue sky, the warm yellow sunlight on the worn ferns and again that green with the pulled lines that seem synonymous with the English countryside. There is a 3D image following on from the CAD flat pattern drawing of the tunic digitally made up on a mannequin.

Indeed, a dyed textile is more than a coloured cloth, it is a record of history. As a designer I look back on the past to design for the new. As part of my way into the textile, I experimented re-using it with new technology: no ‘makeshift’. This is not a pulling together of fabrics lying around but rather a mock-up using a discovered pattern overlaid onto everyday clothes. But what of its texture? What of its drape? Here we have exciting 3D manipulation which results in flat pattern pieces ready to be made. This is experimentation of a different kind. Do we lose something when we use the machine? Or do we gain something? I am using a machine, but I am also being creative. Perhaps Roger Fry wouldn’t like it, perhaps Turnbull would like it, and perhaps Gill would want it made straight away.

By looking into the painted silk from a few historical perspectives I end on concepts of the new, by thinking of the positive links that can exist between art, science and fashion. Perhaps in these times of global brands and mass consumerism, we could learn something from this unfinished silk fragment and its makers.

Sculpture and Decorative Arts including Illuminating Objects is proudly supported by McQueens Flowers.