A Pair of Gold Beakers

Double glass, engraved gold foil and ruby lacquer base

These jewel-like beakers are faceted Zwischengoldglas made in Bohemia 1720-1740. Both feature a lively scene of a stag hunt, with a mischievous smiling hare hidden in each red coloured base. Whilst researching The Courtauld’s collection I was initially drawn to these objects for their delicate illustration. Although they are highly luxurious and use a very experimental technique, upon further analysis I found them to be quite the conversation piece. We can imagine these beakers being used by their wealthy owners, particularly in their simplest form as a special occasion drinking vessel, a glass, a cup, held in the hand or filled with a coloured drink inside. These narratives of the hunt, trapped in gold, glowing and flickering in fire or candlelight, would have created an immersive environment for storytelling.

On these pages I explore the design of these beakers through their making and technique as well as the illustrative scenes on them, using the historical research alongside my own creative responses. This continues the approach to my previous object, the painted silk textile displayed at the Science Museum from May – September 2021. Firstly, I look at glassmaking in Bohemia in the 18th century with a technical history of gold sandwich glass. Secondly, I give a sense of the beakers’ theatricality with a short film clip using light and rotation to investigate the idea of their tactile and sensory engagement with an audience. I also ask design questions about the material of gold through the two related discourses of alchemy and chemistry. Lastly, I use the hunting motif on the beakers to suggest ideas on the sport within the context of forestry issues in the 18th century. I then use these to inspire my own display narrative.

On this page you can find:

- Is All That Shines Gold? A short technical history

- Trapping Gold in Glass Understanding the technique

- Immersive Design Thinking of the beakers – a design object for storytelling

- Materials and Transformations Gold as Alchemists saw it

- Hunting for Meaning Forests and hunting in 18th Century Bohemia

- Capturing a Narrative Ideas that informed the display

Is all that Shines Gold?

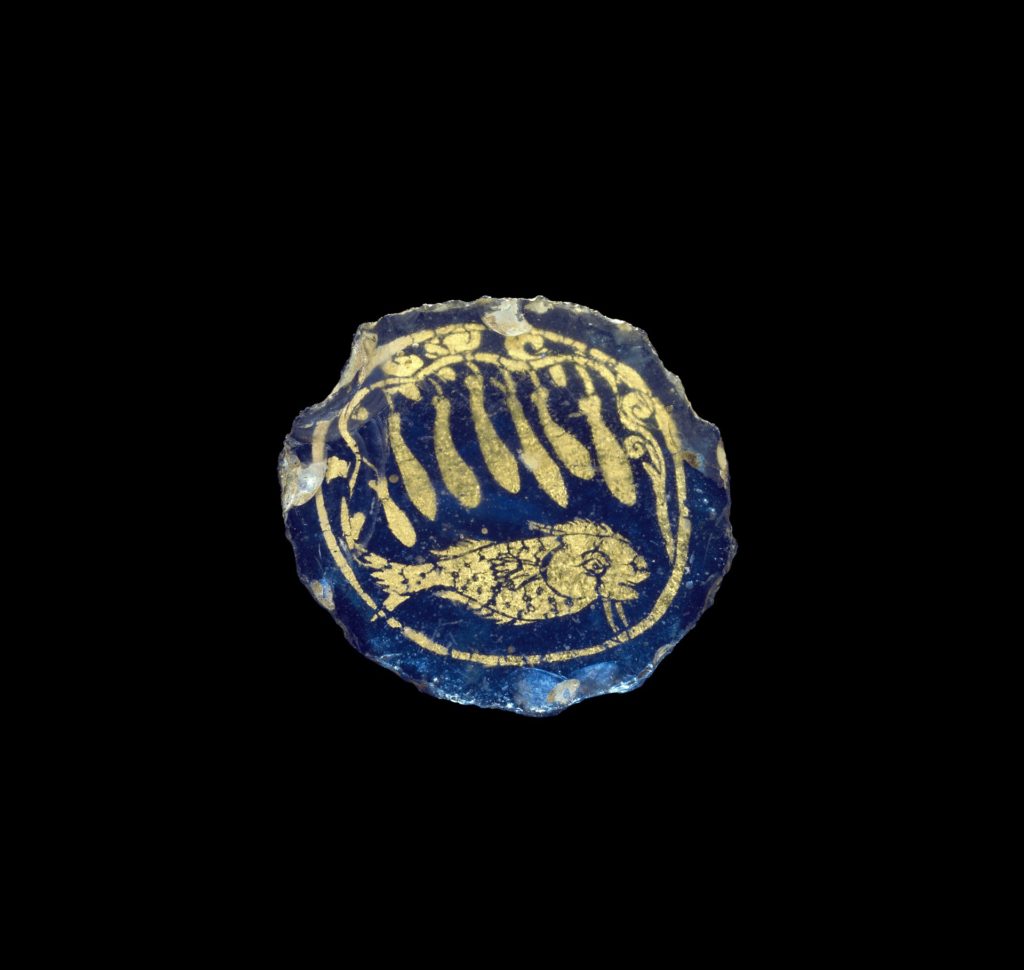

The technique of gold sandwich glass begins in the 3rd and 4th century AD in Ancient Rome. Craftsmen, wanting to use gold to decorate the surface of glass found it couldn’t simply be placed onto the surface without protection. So began the quest of the glassmaker: to maintain shine of the gold within their creation, a challenge that continued to fascinate. This Roman version of the technique was used primarily in the design of flat medallion discs as seen in the example below. The glass was reheated and fused with a melting agent to seal the gold-leaf between the two layers of glass in a furnace, which however dulled the high shine of gold.

Fragment with Fish and Gourd Vine (300–399 CE) Image licensed by The Corning Museum of Glass, Corning, NY

Fragment with Fish and Gourd Vine (300–399 CE) Image licensed by The Corning Museum of Glass, Corning, NYFor reasons that are not entirely clear, this technique was lost towards the end of the 4th century AD, and it was only fully rediscovered in glass workshops around Bohemia and Germany in the 18th century. From there, the production of gold sandwiched glass was coined with the direct translation of the German term zwischengoldglas, mainly associated with the faceted beaker shape from the 1710s.

The first description of the technique of gold-leaf between walls of glass in beakers appears in the book Ars Vitraria Experimentalis, published in 1679 by the alchemist Johann Kunckel. The details of Kunckel’s life are obscure and mostly come from his own writings but he claimed to be a follower of the experimental method. Alchemists were concerned with the transmutation of matter, in particular with trying to convert metals into gold. Modern Chemistry has its roots in alchemy, which brought together chemical experimentation with elements from myths and religion. Alchemy and chemistry employ experimental techniques, such as mixing and heating, to investigate the composition and properties of materials.

The method quoted by Kunckel below described a design that created a marbled effect in the glass. It was later developed into the more complex version of the technique that required the design to be scratched onto gold leaf, which I go on to describe.

“Take two plain glasses, one fitting into the other having the same height. Decorate the outer glass with oil painting like a precious stone and let it dry. Then scratch inlets with a sharp needle, pour linseed oil into the glass, turn it upside down and let it dry until it is only a bit sticky. Then apply the gold leaf, press it well to the walls and let it dry, the scratched inlets will appear as golden. Meanwhile take a smaller glass, coat it with old clear linseed oil, apply the thinnest gold leaf and let it dry. Insert glasses one into the other, grind pure chalk, add oil, make dough, bond the glasses in the rim and let it dry. Coat the joint with oil, let it dry, polish it with pumice, coat with oil, let it almost dry, apply the gold leaf and coat two or three times with oil to protect the gold. This way no one can see that there are two glasses.”

J.Kunckel, Ars Vitaria Experimentalis: Oder vollkomene Glasmacher-Kunst, Frankfurt and Leipzip, 1679, bk. 2, chap. 2, pp12, cited in p. 27 in Journal of Glass Studies Vol. 49 (2007), pp. 103-126 (24 pages)

The period of our glasses 1720-1740 sparked a short-lived spell of experimentation where motifs were scratched into the gold-leaf. Our two beakers are only slightly different in their narrative illustration and differ from Kunckel’s description as they feature faceted sides and a circular medallion inserted in the base. The creation of just one of these glasses would have been the result of the combined work of several skilled craftsmen: mouldmaker, glassblower, grinder/cutter, engraver and assembler. There was a high level of labour producing these luxurious vessels, which brought with it a certain high level of risk in the manufacture, particularly when using costly materials.

Trapping Gold in Glass

This technique was an experimental one, different altered stages were created to fix problems and enhance the process as the years went on. However, the different versions of the technique were not always recorded in writing. They have been surmised from marrying up the documentation (such as Ars Vitraria) with technical examination and observation of the extant glasses, as well as experiments by contemporary scholars, conservators and glassmakers. I have used the article in Journal of Glass Studies Vol. 49 (2007) as the grounding of my explanation of the technique below. As you read this next section please follow along with the drawn diagrams, which I have personally adapted from Eva Rydlova’s article Zwishengoldglaser from the Museum of Decorative Arts in Prague.

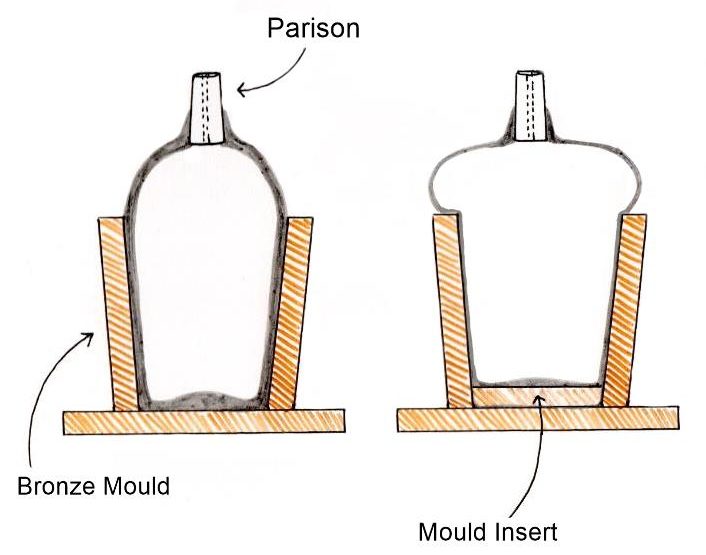

The starting principle is that there is an inner and an outer cup eventually to form the whole beaker. The inner cup being smooth and the outer cup being a faceted edge. These two cups are then blown in a metal bronze mould due to the high level of precision needed that would not have been achieved from a wooden mould. The shape of the mould is open, tapered, with straight sides and a round interior. Bronze is a good metal to use as it retains heat well to keep the appropriate temperature for long periods of time. However, blowing the glass into the mould is risky and tricky, the thickness of the wall needed to be maintained with variants in the speed of blowing and temperature.

When blowing the piece of glass, a parison (an unshaped mass of glass before it is moulded into its final form) is on the end of the blowpipe and is heated horizontally. The mould starts on the floor and then the blowpipe is moved vertically and inserted into the mould, stretching the glass over all the inside surfaces of the mould. To alter the thickness of the rim you can give the inner cup a small over-blow and the outer cup a large over-blow as seen in the diagram. An expert glassblower could make both cups from the same mould. With only the slight modification of placing an insert in the bottom of the mould for the outer cup to create the two nesting cups.

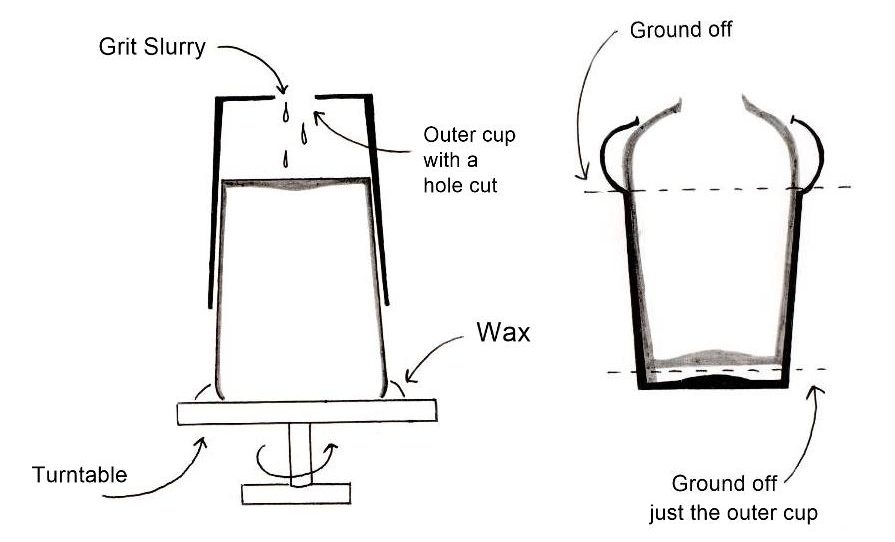

To form the final shape there is a long and lengthy grinding process to create the perfect fit. This is a highly risky process because each step involves heat building up which could cause the glass to break. Many blown cups therefore did not make it to the assembling stages. To get the two cups to fit exactly together, the inner cup is placed upside down on a turntable and the outer cup has a hole made in the bottom so that a grit slurry can be poured between the two glasses. The inner cup is then turned and the outer cup is held still which grinds the two pieces together. A further satin polish is used to get the surfaces ready for gilding on the exterior surface of the inner cup and near the rim on the interior surface of the outer cup. Next, the outer cup has the bottom ground off which leaves the cup to become a sleeve. In this form, it is very vulnerable as it is only a cylinder. The two pieces are temporarily assembled to cut the facets and to attach a plug at the bottom of the sleeve that is cut out of flat glass. Therefore, even before any of the gold is used this is a very unusual, and highly technical technique to get right.

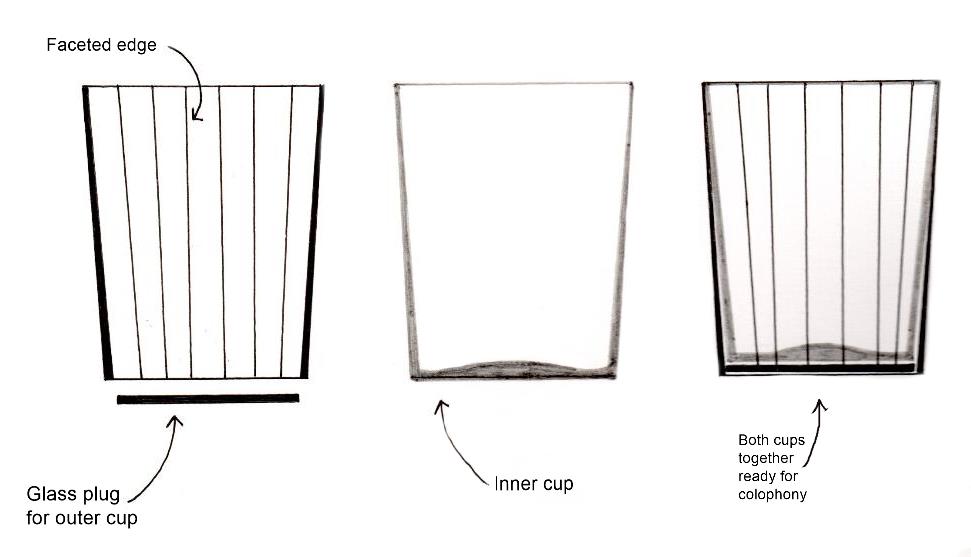

At a later stage, gold leaf is applied to the outer surface of the inner cup and the motif (in this case hunting) is scratched through with a metal tool in thin delicate lines. The two glasses are then joined together, by placing the decorated inner cup on its rim and placing the sleeve over. Colophony (a solid form of resin obtained from pines) is heated to melting point and is then poured in through the open bottom. Once the colophony has filled all the space between the walls the plug is inserted. If you shine a torch at our beakers, you see air bubbles in the walls of the glass from the colophony, which were very difficult to avoid. The junction at the lip is ground smooth and sealed at the top to make the glasses waterproof and fit for use. The colophony stage is another point of high risk. Many glasses show frequent cracking but would stay held together with the resin. Many damaged versions still exist because of the enormous amount of time and cost invested into the pieces. These were kept as test pieces and samples for learning. The Courtauld beakers show no flaw, therefore not only are they special objects, but they are also rare successful objects that evoke the inherent perfection of the process.

Immersive Design

These beakers are touchable object, that in their creation have passed through many skilled hands. They were made to be drunk from, celebrated with or perhaps used for the drowning of sorrows. The decorative scene suggests that they were made as exclusive gifts, but in addition to hunting scenes, religious motifs often appear on such glasses, particularly figures of saints as well as bountiful gardens, castles or monasteries. Speaking to Jana Černovská from the Museum of Decorative Arts in Prague, who have more than 300 vessels in their glass collection, she agreed that the theory of a post-hunt toast is quite possible and that Bohemians drank a lot in this era, often toasting with various spirits such as plum or pear brandy.

By holding the object in your own hand and rotating it, the narrative of the silhouettes creates a double-image effect, like a dream sequence or an early moving image. They remind us of a zoetrope: one of the first pre-film animation devices that created the illusion of motion by displaying a sequence of drawings of each stage of a motion. You can see an example from the Science Museum Group collection here. As seen in the film below we can imagine an evening of storytelling with the beakers as props, flickering in the candlelight, creating a magical atmosphere, an immersive environment for telling a story.

We can draw upon our senses to study the object; what is it like when we hold it? How would we hold it? What time of day would it have been used? How does the gold leaf exhibit itself in the light? How would the image change with different coloured liquids in the glass? Would we sip out of it or gulp it down in one shot? – cut the video

What we see is that the illustrations are not just moving silhouettes. They are silhouettes formed out of blended gold, setting our scene between two walls: one of mastery and technique and the other of mystery and storytelling. The gold forms move in a new way, becoming abstracted and magical in the light. The hunters and the stags are no longer themselves; they move into a different dimension. We, as the audience, are still intrigued by gold and its mystery, like the alchemists of the past.

Materials and Transformations

“What then is matter? What do we mean when we speak of materials? Are matter and materials the same or different? To understand the meaning of materials for those who work with them – artisans, craftsmen, painters, practitioners of other trades – I believe we need ‘to take a short course in forgetting chemistry’ or more precisely, we have to remember how materials were understood in the days of alchemy.”

Tim Ingold, Making, 2010.

As a masters design student, I look to academic writing in different disciplines to understand the needs of making and designing. Upon reading Making by the anthropologist Tim Ingold, whilst researching the history of alchemy, I found this quote particularly useful for thinking about the zwischengoldglas materials and technique in that period. Separate knowledge and skills were needed with specific experience to mix the right raw materials and to understand the correct interactions of the experiments. This is where alchemists came in.

To understand the difference between alchemy and modern chemistry we can look at two definitions of the substance in our beakers: gold. A chemist might define gold as an element, as represented in the periodic table by its chemical symbol ‘Au’. They might add it is a transition metal, one of the least reactive chemical elements and can be made into many forms and appearances. In alchemy the symbol for gold is a sun, stemming from mythology with gold relating to the sun. View this alchemical scroll from the 18th century, with sun imagery and other alchemical symbols. Some alchemists would see gold to be the origin of all metals. Anything that was yellow and shone brightly, that could be even brighter when seen in water, and could be hammered into thin leaf, was gold.

Alchemy has popularly been characterised as an obsession with artificially manufacturing gold and alchemists have often been portrayed as strange and mystical individuals, leading alchemy to becoming linked to the occult. Some of these characterisations were made by early chemists, wishing to distance their practice from alchemy to establish its rational credentials in the Age of Enlightenment. But there was much crossover between alchemy and the emerging science of ‘chymistry’.

For alchemists like Kunckel, the aim was to try to understand natural occurrences. They simulated natural processes in their laboratories by mimicking the same conditions, and from these experiments attempted to explain and give theories to natural phenomena. You can read more about the alchemy of glass making on The Corning Museum’s website, which explains how gold was seen by the alchemists experimenting with glass.

Hunting for Meaning

We know the beakers have gold leaf between glass, but what of the glass itself? The Bohemian land use of the time gives us our story, as well as looking back to our beakers’ hunting narrative. In the 17th century, forests were cleared both for agricultural land and to obtain the wood needed for firing the kilns. The substance potash, which was used in glassmaking as an alkali as it could withstand higher temperatures to create a clearer glass, was a by-product of this deforestation. Potash is a potassium-rich salt that is mined from underground deposits that contain potassium in water-soluble form. It was made from collected wood from the forests and the wood ashes were soaked in water. Evaporating the resulting solution in iron pots, however left a white residue. Bohemian glass-workers discovered that when they combined potash with a lime chalk they were able to create a clear colourless glass.

This land was not only used to benefit the glassmaking industry, in 17th Century Bohemia hunting was at its most popular and this was known as the golden age of gamekeeping. Hunting was a major entertainment, with parties and grand hunting festivals popular with the nobility. However, in the 18th century, concern and complaints about the severe losses in some species led to a decline in hunting and increasing interest in forestry. Hunting game gradually decreased as this was considered to be a danger to forests and to agriculture. According to the foresters, the character of the forests had changed considerably during the previous centuries and in 1719 the game inspector for the Český Krumlov estate wrote “The main hindrance for deer breeding is excessive hunting and a lack of right habitat.” Throughout the century strict rules and forestry regulations were introduced for appropriate game hunting. Hunters were taught how to read animal tracks in forest snow to facilitate the hunts. Passes and roads were made in the woods. Great care was taken to clean all of the hunting grounds of trodden areas, and tree felling ended to care for animals’ habitat. Careless gamekeepers were punished, and poachers persecuted.

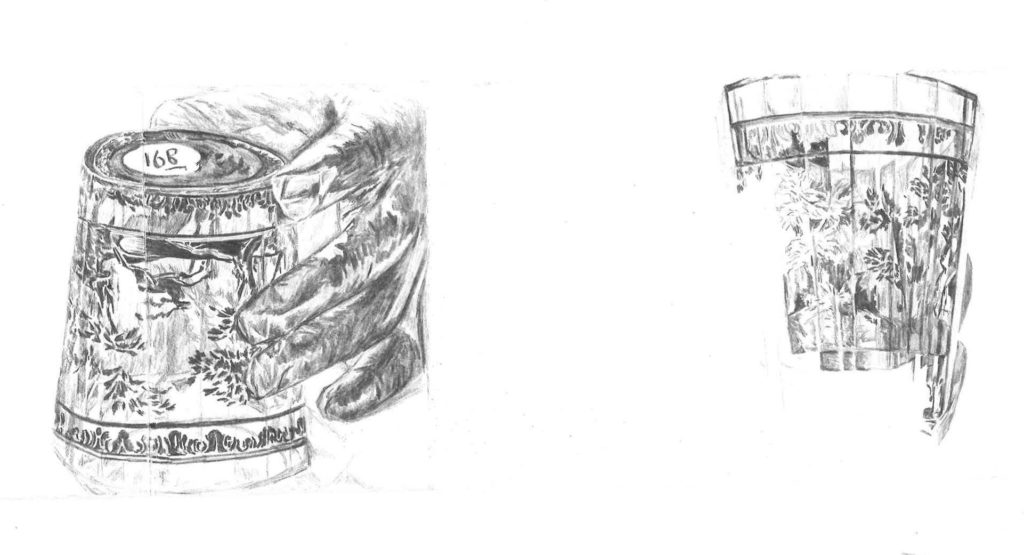

Comparing the trees, deer, hares and hunters on the beakers

Knowing this history subtly changes how we see the beakers today. The sandwiched gold almost seems to dim, nostalgic for its literal golden age. I imagine a once-celebrated custom of sitting around the candlelight and discussing your day’s hunt having become tarnished and outdated in the following century. And yet the most popular decoration on these types of beakers remained hunting scenes and we do not know why. If we take a closer look at both beakers we can remark upon their slight difference in narrative. One of the beakers has three broken trees in succession. One tree is merely a ragged broken tree trunk, another grown tall yet with snapped broken-off branches with no full leaves. A coincidence, perhaps, but why does one beaker have perfect trees all intact and another not? How and why have these trees been damaged? I came across these through drawing out the narratives for the display. We can only speculate whether these were in retaliation to hunting or even deforestation.

Capturing a Narrative

If we flattened the illustration out and it became a story board, where would we choose to start the story, where to end it? We can alter the story and its meaning. What would our modern-day hunt be on our own everyday drinking vessel? In the display of the beakers at The Courtauld gallery I wanted to bring together the hunting and alchemy strands from my research and sit the beakers in an ‘everyday’, ‘used’ type of setting. You will see the beakers, their narrative drawn out and positioned carefully around selected objects and books.

Firstly it was important to show the storytelling element for the visitors so their imagined narrative could be followed around the case. Drawing on my own practice and looking at my own worktable and physical art space this led to conversations about the workspace as an art object: the idea of capturing something mid process that allows the visitor to have a fluid interpretation of the piece. Talking to The Courtauld Technician Matthew Thompson we looked at trompe l’oeil paintings for inspiration. We then tried to imagine the worktable in an alchemist’s workshop or the table surrounded by the elite drinking post hunt. We began to muse upon 18th century still life painting, seeing tools and items of functions within paintings and how those themes could be applied to the beakers, particularly as they were going on display in the new 18th century room. Make sure to look out for the silver Fox mask stirrup cup 1773-74 from Louisa Courtauld’s and George Powells’ collection displayed in the large case of the same room. It was used to serve a fortifying drink before the start of the hunt, where it would be served to the hunters on their horses. A nice link to our beakers’ role of an after-hunt toast.

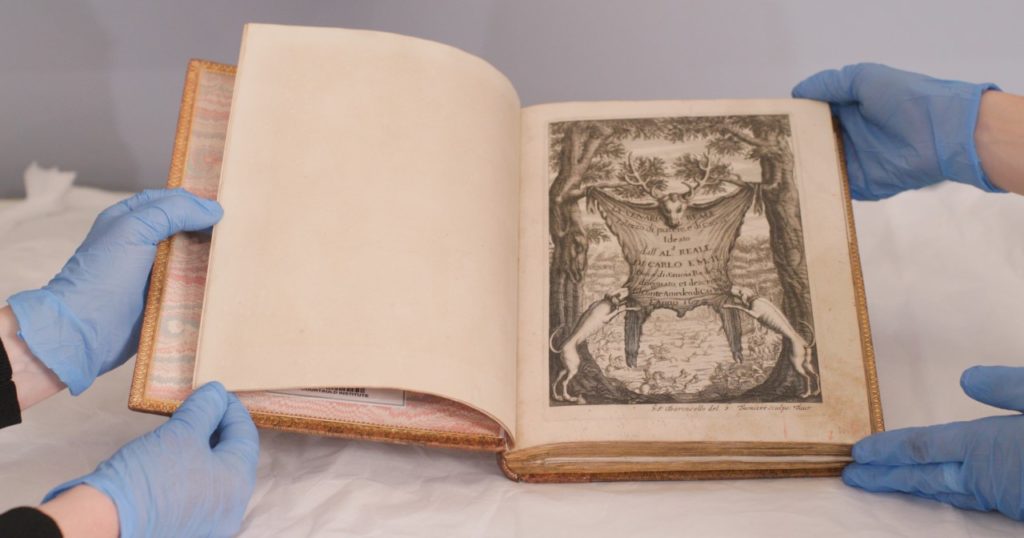

Our aim was to draw out the hunting narrative from the glasses into the gilding objects and books from The Courtauld Library’s Anthony Blunt Collection. You can browse more of their books here. The items that we finally chose we felt gave an underlying merging of the themes of hunting and alchemy. Take a look at the insides of the books on display and look out for the golden gilded animals on the spine of the brown leather book.

This hunting book became the perfect piece to tie together the tools of gilding the dark underlying tones of hunting and alchemy. See this terrifically detailed image of the flayed deer.

The second book on display, Proteus ofte minne-beelden verandert in sinne-beelden / door J. Catz, d.1627, is bound out of vellum, is a very fine calf skin. This echoes the stretching out of the skin in the image above of the deer as well as the stretching out of covering the book.

This painting by Willem Claesz Heda Still Life of a Roemer and a Facon de Venise, 1630 inspired our final display of the glasses and how we set the scene. The empty glass on its side (fallen) is supposed to signify fragility of life in Dutch still life paintings. This ties in with our velvet falling out of the beaker, symbolising both spilt blood from the hunt, but also the plum brandy drunk to celebrate a kill. The knife here is crucial as it emphasises the dual role the object has in the gilding process whilst hinting at the flaying of the deer in the leather-bound book. The knife in many Dutch still life compositions are precariously placed, a shifting object with a potential underlying threat.

The overall arrangement of the display is a gathering of the research from this webpage: to highlight the intricate and unique glassmaking technique of the time; to bring the visitor into the story through making a physical scene rather than an moving silhouette; to show the hunting context of the glasses and to understand the way alchemist looked at materials. Above all the aim of this project has been to showcase the delicate beakers in a way they have not been seen before. To show that they are touchable, usable vessels.

This webpage has been researched and written by Sophie-Nicole Dodds as part of the Illuminating Objects Series. Foremost thanks to McQueens Flowers for their support, and to Richard Eagleton in particular for his energy and enthusiasm. Special thanks to Rupert Cole at The Science Museum, London for his guidance on the difference between chemistry and alchemy and to Jana Černovská from the Museum of Decorative Arts in Prague for the knowledge of the beakers drinking substance! A huge thanks to Matthew Thompson from The Courtauld for his collaboration, inspiration and wonderful discussion on the display on the glasses, I couldn’t have done it without him. Finally, I am deeply indebted to Katy Barrett at The Science Museum, and Alexandra Gerstein at The Courtauld Gallery for their abundant knowledge, wise and enlightening counsel.

Sculpture and Decorative Arts including Illuminating Objects is proudly supported by McQueens Flowers.