It is unusual for a storage jar of this type to have such a complex and contrasting design painted on the reverse, which normally would not have been visible when the jar was placed on the open shelving of a pharmacy, for example. This style of decoration, known as grotesque, features a symmetrical arrangement of monstrous and mythical figures. It developed from a type of wall decoration used in Ancient Rome. The grotesque became fashionable in the Italian Renaissance, and artists used it in various media, especially in ceramic design.

Another typical feature of that period was the painting style observed here: grisaille, referring to the exclusive use of different shades of grey or other neutral colours in an attempt to imitate stone sculpture. Artists often used grisaille for underpaintings or for modelling sketches as they could complete their work more quickly without the addition of colour. Some artists chose it for aesthetic reasons. The gloomy palette of the decoration on this jar aligns with the grim grotesques.

Covering the jar, we find nightmarish creatures with serpentine bodies and oversized dragons’ heads. They appear to be growing outward from a ‘body’ that also features a pair of heads. Swirling acanthus leaves stem from the figures. All these elements are typical of Renaissance grotesques and were heavily inspired by a book called the Metamorphoses, a Latin narrative poem composed in 8 CE by the Roman poet Ovid. In this work, Ovid revisited earlier literature and myths via a transformative approach. Humans turn into trees, animals turn into stars (constellations), and features like gender and body colours also are fluid and transitional. This fluidity in physical forms aligned with the irrationality valued by grotesque artists. Moreover, as suggested by Vannoccio Biringuccio, an Italian metallurgist from the 15th century, metamorphosis is a relevant theme in pottery decoration. These themes find a parallel in alchemy, which is the art of transmutation. Again, we are not sure if the storage jar contained ingredients that were believed to produce such (alchemical or transmutational) effects, but the use of grotesque decoration does make the object even more intriguing and mysterious.

Close-up images of the pharmacy jar (back). Photo © The Courtauld.

The drooping eyelids and exposed teeth of the twinned heads encourage us to wonder about their strange presence. Are they dreaming, in pain, or in a semi-conscious state? Could their fearful expressions function to ward off disease, or even to warn against the misuse of the jar’s contents? If so, could an overdose induce hallucinations, visualised as the multiplied, fantastical characters here depicted? The blurred, unconscious state that these figures evoke can remind us of Sigmund Freud’s The Interpretation of Dreams (Die Traumdeutung) and his psychoanalytical investigations of the late 19th century. Freud’s works have indeed been debated and are sometimes regarded today as ethically controversial. In the early 20th century, surrealism in art and literature derived from the idea of probing into subconscious minds. It looked at altered reality with dream-like, irrational features.

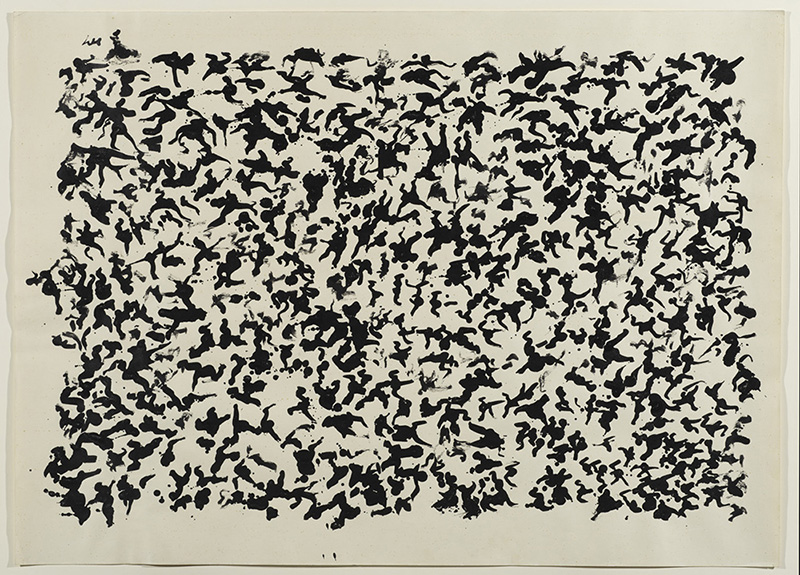

Meanwhile, some Surrealists and later artists also experimented with making art under the influence of narcotic or psychedelic drugs. Among them was a French artist named Henri Michaux. He introduced the poet Unica Zürn to experimenting with mescaline. He made drawings inspired by his own experiences with mescaline. One such drawing is in The Courtauld’s collection.