By Ruby Redstone

MA, “Documenting Fashion: Modernity, Films and Image in America and Europe, 1920-1960”, The Courtauld, 2020-21.

Last night’s Fashion Interpretations Symposium featured a masterclass with celebrated fashion illustrator Richard Haines. Haines began with a nod to fashion history, showing a selection of his favourite works by early twentieth century illustrator Christian Bérard, whose work Haines loves for its unwavering, confident lines. Particularly inspiring for Haines is the trompe l’oeil door Bérard created for the Institut Guerlain in Paris which appears from afar to be painted but is, as Haines discovered on a recent trip to Paris, comprised of small strips of grosgrain. Ruminating on this discovery, he remarked: ‘A line can be a piece of paper and a pencil, it can be charcoal, it can be Procreate, or it can be a strip of grosgrain’.

Haines continued this rumination on the concept of line, demonstrating how his hand responds differently when sketching contemporary clothing than it does when sketching archival looks from designers like Schiaparelli, of whom he is a loyal fan. When sketching the 1930s, he explained, he gravitates towards gentle, curvaceous lines. When sketching contemporary designers, like his particular favourite Christpher John Rogers, he finds that he naturally tends to use bolder, more graphic lines and emphasises the shape of a look more than its finer details. Haines also provided examples of different media in his body of work, noting the nuances of his works in pastel and charcoal and his newer works created on his iPad. ‘To me,’ he remarked, ‘there is nothing more beautiful than a drawing. But [with digital technology] we are adapting the drawing and putting it in different contexts, and that is so exciting’. He draws inspiration not just from his subject matter but from the vast array of media he is able to use to render it.

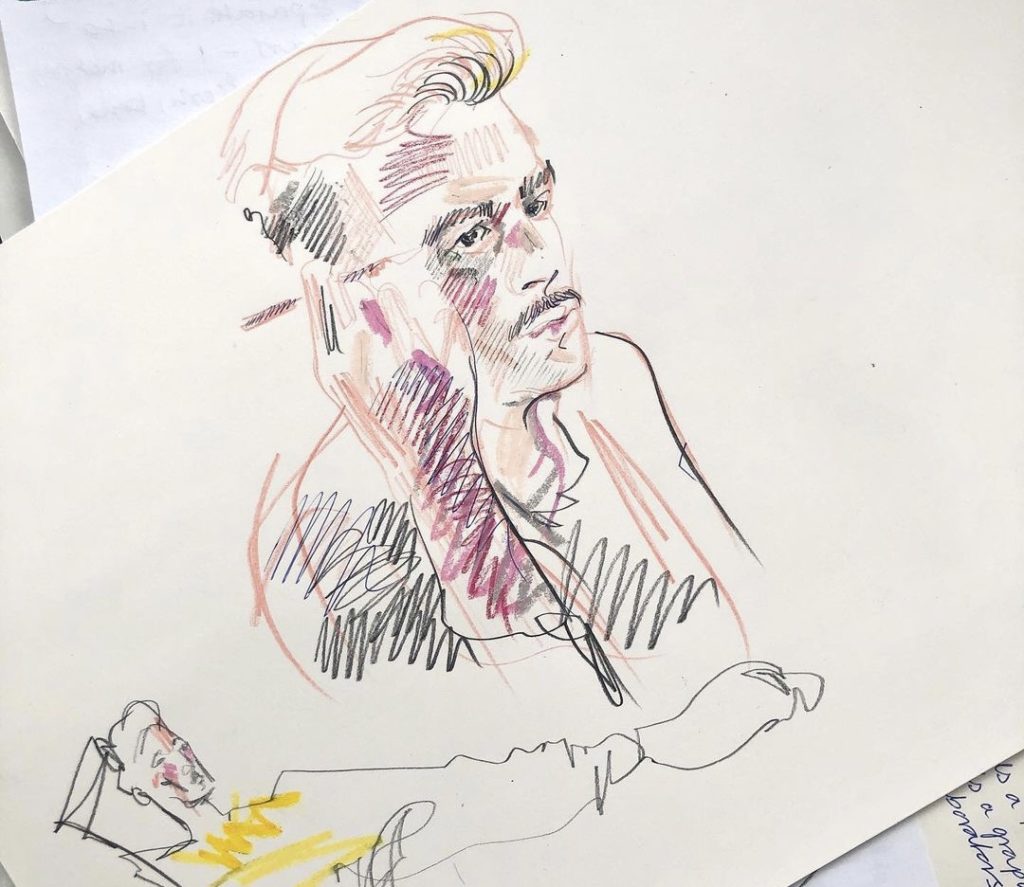

Haines then (virtually) brought in a model and led his audience through a thirty minute session of rapid-fire sketching. During this time, he provided practical illustration advice that he has garnered throughout his wide-reaching career in fashion. Haines always begins his drawings from the head down and focuses on capturing the gesture of a model’s pose quickly. In fact, he explained how he prefers to create most of his works in a short frame of time and avoids getting hung up on imperfections and fussy details–undoubtedly a factor in his drawings’ trademark liveliness. This can prove challenging when working for a commercial client, as Haines has to work in a client’s corrections without compromising the spontaneity of his style.

Most crucially, Haines believes that one should never take an eraser to their sketch. He makes confident marks on his page and, should he make a mistake, he works to change the line he is creating and manipulate it into an integral part of his drawing. Should any of us be lucky enough to be invited to sketch a fashion show like Haines, he warns us to be careful with the medium we select. Years ago when sketching at the Oscar de la Renta showroom, he knocked over a pot of India ink and nearly ruined the designer’s handiwork. He now favours a charcoal stick for these high-pressure situations. Confident lines are, of course, better left on the page than the showroom floor, but for Haines, the page seems to always provide enough room for boundless exploration.

If you sketched along with Haines, please do share your drawings under #richardhainesmasterclass, and browse the hashtag if you’d like to see others’ work! Join us tonight for the final night of the Fashion Interpretations Symposium which will be a special roundtable discussion to celebrate the launch of Archivist Addendum.