In her introduction to the glossy photobook National Geographic Fashion, the anthropologist Joanne Eicher writes: ‘fashion is, after all, about change, and change happens in every culture because human beings are creative and flexible’ (2001, p. 17). The suggestion is that fashion does not have to be characterised only by rapid change in clothing and appearance styles, which have crystallised it as a distinctly urban, ‘Western’ phenomenon. Rather, Eicher reiterates that fashion is a lived experience, which has existed in all cultures, at all times – but may take different forms and paces of innovation. My project for Fashion Interpretations takes this bold assertion – which constitutes a critical decentring of what ‘fashion’ is – as its starting point.

I’m using an equally expansive definition of fashion to problematise my understanding of modernity and modernisation as it unfolded within Brazil in the first part of the twentieth century. What sorts of possibilities does the Global South offer to explore fashion in new contexts and different mediums? Does fashion have to emerge in the city, or can it exist in any flourishing society? Could my findings help to reposition European fashion as simply one system – one experience of modernity – that operates in parallel to, sometimes in competition against, but frequently in exchange with, numerous alternative fashion systems operating globally, not all of them capitalist?

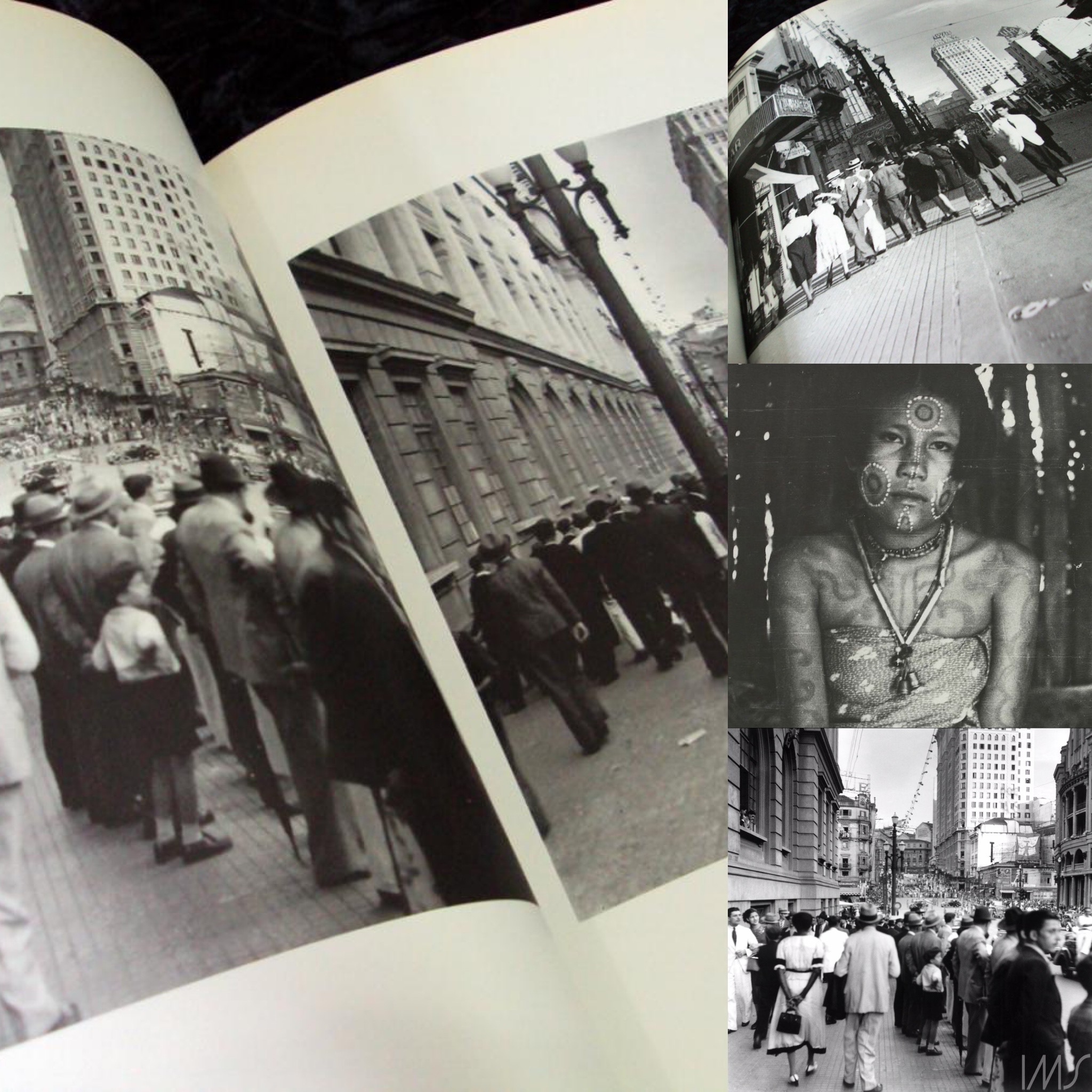

I want to begin my blog post with a story, in much the same way that fashion is a powerful medium for telling stories. In 1935, a 26-year old academic, accompanied by his wife, travelled from Paris – the capital of haute couture – to São Paulo, a city rapidly on the move, in order to help establish the University of São Paulo. The couple documented the changing landscape of São Paulo, which was undergoing modernisation, industrialisation and urbanisation, as well as witnessing emerging consumer cultures. Their cameras captured people on the city’s streets sporting European fashions adapted for warmer climes and diverging tastes. Whilst in the summer holidays, the couple escaped the city to conduct ethnographic fieldwork in Mato Grosso, a large state in Western Central Brazil. They collected items of visual and material culture from the Bororo and Kadiwéu indigenous peoples that they encountered, in addition to documenting their extensive sartorial systems. The couple returned to France with this knowledge (that equated, of course, to power), where it was held by the Musée de l’Homme (now part of the Musée du Quai Branly). Their names were Claude and Dina (née Dreyfus) Lévi-Strauss.

My aim over the next few months is to use the Lévi-Strauss’ photographs that exist in archives in Paris and São Paulo to think deeply about where fashion is located. What role does medium play in enabling us to recognise fashion in new contexts? At what point does dress become fashionable by association? I’ll use fashion as a tool to explore the shifting power relations that underpin the world we live in. I’m excited to share these ideas with the inspiring individuals involved in this network…