During our study trip week I travelled to Walsall in the West Midlands, England, to visit the Walsall Museum’s Hodson Shop archive. This archive consists of the unsold stock of the Hodson Shop. This small draper’s and haberdasher’s shop was opened in 1920 by the twenty-nine-year-old Edith Hodson in the front room of the Hodson family’s home in the industrial town of Willenhall. Edith’s younger sister, Flora, joined the business in 1927, while their older brother Edgar ran a lock factory from the courtyard. After the death of both Edith and Edgar, Flora continued to run the shop until the early 1970s. The abandoned shop stock was discovered in 1983, after Flora’s death, and was passed on to Walsall Museum, where it is now curated by the lovely Catherine Lister.

Sheila B. Shreeve, who has meticulously catalogued the collection of over 3000 dress items, was working as a volunteer at Walsall Museum at the time of the shop’s discovery. Shreeve’s description of her first encounter with the abandoned shop pretty much sounds like the stuff my dreams are made of: “Imagine my delight when I first entered the front room of the locksmith’s house and found it to have been a draper’s shop. Boxed were piled haphazardly on flimsy shelves, slim and elegant leather gloves were strewn across the floor. On the oak counter was a display box which revealed rolls of shimmering silk ribbons abandoned when superseded first by rayon ones and then by nylon” (Shreeve, 82).

As Shreeve points out, the collection of unsold garments, dating from the 1920s to the early 1960s, would have been worn “by the ordinary men, woman and children in the street”, the local working-class and lower middle-class. (Shreeve, 82-83). By looking at the Hodson Shop archive one gains a fascinating insight into the ‘everyday’ life of the non-elite in the West Midlands area in England.

Besides women’s, men’s and children’s clothing, the collection also contains haberdashery items, dressmaking and needlework magazines, cosmetics, and household goods. Moreover, boxes of printed items, such as warehouse and other supplier catalogues and leaflets, give an insight in the business side of the shop.

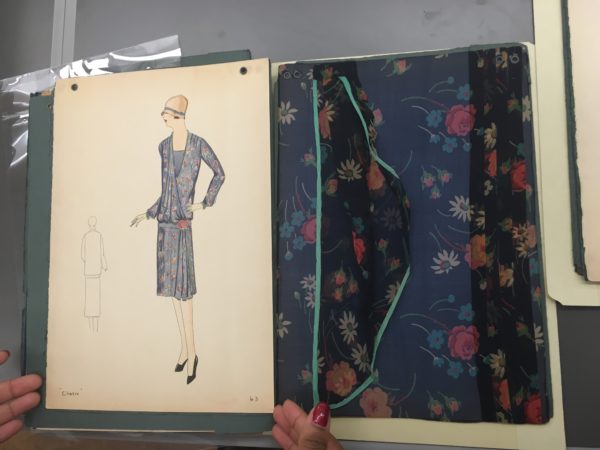

What I absolutely loved about my visit was to see the way this collection has been catalogued. Besides giving a dense, detailed description of the style, material and size, Shreeve has made a small drawing depicting the garment, with relevant details such as pleats, pockets, or fabric print. These drawings give a wonderful visual overview of the collection, and also show fashion’s changing silhouette over time.

Shreeve has added more ‘layers’ to this collection, as she has created a separate catalogue record card for each garment. Moreover, in the case of some garments, Shreeve has found cross-references in the form of advertisements in the warehouse catalogues. These advertisements give us additional information. For instance, a sleeveless blouse made of artificial silk was advertised in the Spring 1931 catalogue of Wilkinson & Riddell Ltd., a warehouse based in Birmingham. The blouse was available in the following colours: “ivory, sahara, champagne, nil, and powder”.

Because the Hodson Shop collection is “dead stock”, as it was never sold to and used by consumers, the clothing I looked at was overall in a crisp and pristine condition. This dead stock condition fascinated me, as these were garments that were made to be worn, but never worn in the end. Even so, on the back of a beautiful navy blue crepe dress manufactured by Belcrepe from c. 1936, which had the original swing ticket still attached, I noticed an interesting pattern of discoloration caused by fading. This dress showed, in an almost eerie way, what time – and light – can do to a garment that has never been worn and has been stored away.

By Nelleke Honcoop

Further reading:

Shreeve, Sheila B. ‘The Hodson Shop’. Costume 48, no. 1 (1 January 2014): 82–97.

Blog written by Jenny Evans about her PhD on the Hodson Shop: https://hodsonshopproject.com/

Online database of the Hodson Shop: www.blackcountryhistory.org