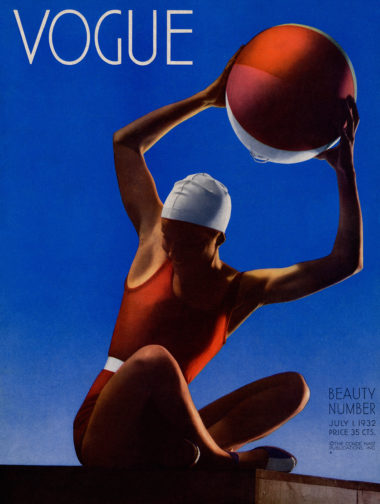

As coloured photography started to seep into the pages of Vogue during the 1930s, it shifted the ways in which fashion consumers and spectators appreciated the dressed body. Simultaneous to this technological progress of fashion magazines was the modernisation and arguable liberation of the body itself. The first in-colour Vogue cover by Edward Steichen in July 1932 attests to this. Playfully raising a beach ball above her head, the model is sporting red swimwear with a white belted detail to emphasise her lean frame, and a white cap. Mirroring the colours of her ball, her vibrant body juxtaposes the gradated blue sky that upwardly intensifies behind her. This is an image of colourful contrasts; red stubbornly clashes with blue, white breaks up the composition, and even her shoes are two-toned. The depth of the colours evoke a sense of warmth and humidity. We can only hope to be transported to where she is and to look as chic as she does in a swimming cap. Perhaps buying Vogue will help get us there…

Although shot indoors in the studio using a 108-inch plate camera that Condé Nast insisted his photographers work with, Steichen’s lighting techniques evoke summer evening sun. This convinces the viewer that the model has spent an entire day of leisure and sport at the beach. The connoted low sunlight highlights the contours of the model’s armpits, her toned arms, wrist tendons, sharp elbows, the dents on her knees and the overall sculptural quality of her tanned body. The white segment of the beachball that orbits her athletic frame evokes a waning crescent moon, perhaps signalling that dusk is approaching. Her shadowed face creates a canvas of anonymity onto which the Vogue reader can project themselves. We can see that she is smiling in unapologetic enjoyment. Her averted gaze suggests that she is unaware of being watched, or even being photographed in an inorganic, staged setting.

Aside from a hint of feathery eyelashes, her body is totally hairless, stressed by the cap that protects her hair from seawater and the unrelenting sun. This evokes the smooth, marble-like texture of her skin. The primary colours evoke a sense of childish playfulness; this is a woman unshackled by social convention or responsibility. She embodies care-free leisure as well as women’s progressively and fashionably active lifestyles. Having been exposed to this vibrant image, it is hard to imagine what her body, or the overall composition, would look like in black and white.

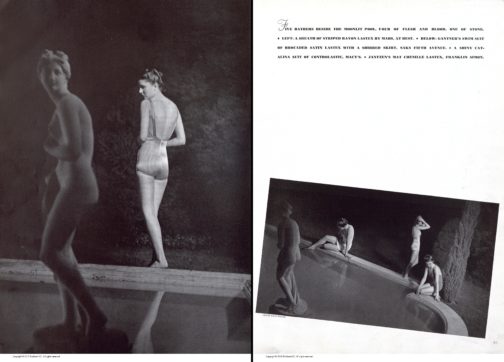

Harper’s Bazaar’s swimwear editorial from June 1939 stands in stark contrast to the highly saturated cover of their rival Vogue. Shot in black and white, the models’ skin takes on the luminosity of classical marble statues. Unlike the evocation of the setting sun in Vogue’s cover, here we get a sense of bright moonlight illuminating exposed flesh. In the image on the left, a woman stands with her back to us, reflecting the pose of the statue situated in the centre of a pool within a secluded wood. This mirror-image establishes a direct connection between woman and sculpture, as if the touch of moonbeams has metamorphosised her from antique marble into living, breathing flesh. Her closed-off body language could suggest that she senses she is being watched in this intimate moment of midnight bathing. The article reads ‘five bathers beside the moonlit pool, four of flesh and blood, one of stone’, which heightens the idea of mythical transformations.

The model’s striped swimsuit takes on a silvery quality and the low scooped back exposes the gentle curvature of her spine. The image on the right depicts three more models poised tentatively on the edge of the pool. They resemble mythological nymphs bathing out of view of mortal eyes. Their poses are fairly natural; their bodies have not been manipulated to cater to the male gaze, perhaps explained by the female photographer Louise Dahl-Wolfe and the predominantly female readership of Harper’s Bazaar. By presenting the female body at different angles, it offers a three-dimensional, sculptural appreciation of the body as well as a well-rounded impression of the swimwear. Their toned bodies highlight that these are active, modern women. There lingers a sense of seclusion and privacy through the implicit separation from the male gaze. Fashion magazines including Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar promoted exercise regimes linked to classical ideals of athleticism, which were often untaken in separation from men. This image potentially evokes this secure seclusion away from prying eyes. In this instance, even when women are depicted as active and exercising, they still retain a sculptural quality. Perhaps if this image had been captured in colour, it would imbue their statuesque bodies with vitality and thus reflect the cultural shift towards women’s more dynamic and active lives.

By Claudia Stanley

Sources:

Rebecca Arnold, ‘Movement and Modernity: New York Sportswear, Dance, and Exercise in the 1930s and 1940s’, Fashion Theory, vol. 12, no. 3 (Oxfordshire, 2008), pp. 341–57, https://doi.org/10.2752/175174108X332323

Susanna Brown, ‘Introduction: Inventing Elegance’, Horst: Photographer of Style, exhibition catalogue, Victoria and Albert Museum (London, 2014), pp.11-21

Harper’s Bazaar, June 1939, New York Vol. 72, Iss. 2724