Moschino’s Spring/Summer 2018 ready-to-wear collection designed by Jeremy Scott is inspired by biker ballerinas, Hasbro’s ‘My Little Pony’, and flowers. An eclectic group of influences that are not aesthetically comprehensible but work insofar that the designs make the models look as if they are playing dress up on the runway. The designs make sense as a presentation of dress-up in the way they are in direct conversation with the runway design itself. The show’s threshold is shrouded with vegetation and overflowing with flowers of all different sizes and colors. The Moschino brand name is visible on the threshold only as a trace, an imprint created by negative space. The runway is made of glass and appears black, reflecting the walls that surround it—making it seem as if the models are walking in a fantasy space. The models reject ‘types’ through what they wear. Instead of being either ‘the biker’ or ‘the ballerina,’ they are both. Scott’s designs for Moschino expose how fashion shows can be taken too seriously in terms of how they can present a new standard of dress for women and instead the show parodies that notion through dress-up. The joke is particularly visible when the models walk out dressed as various flowers–the ultimate gift-object in society–which is often a metonymic representation for women in general. Scott’s use of humor in his designs to reject presentations of standards of dress for women, which makes visible the spaces in which women are told to exist are actually quite fetishistic and unsettling.

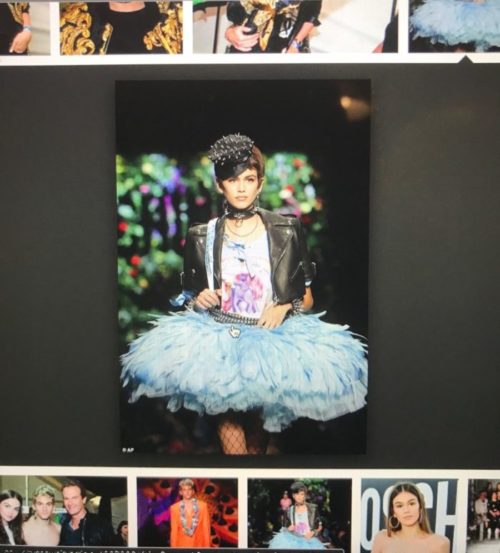

Supermodel in-training, Kaia Gerber, opens the show. Gerber wears a feathered light-blue tutu, “My Little Pony” t-shirt paired with fishnets, black leather combat boots, and a black leather jacket (fig.1). Gerber’s look sets the tone for the biker-ballerina designs by Scott. The mixture of hard lines created by the biker aesthetic and the soft lines and colors of Hasbro style in conjunction with Gerber’s almost seraphic face further establishes the show’s theme of dress-up.

There is no fluid transition between the first act and the second act of the show. Anna Cleveland opens act two by sauntering onto the runway dressed as a pink lotus flower picking out her own petals (fig 2). Scott’s flower-wear took the shape of lilies, roses, orchids, tiger lilies and tulips. The show ends with Gigi Hadid, literally dressed as a gifted bouquet of flowers (fig.3). The end of the show makes the viewer aware that the models (or flowers rather) were all gifts to be received by the eye. Scott complicates this in that Hadid’s make-up does not fit with the rest of the flowers that frame her face. Her make-up makes her appear older. Hadid’s face stands out amongst the flowers instead of blending in. Jeremy Scott’s designs use dress up as a means to complicate how clothes, our second skin, can actually reveal the physical body even more.

By Destinee Forbes