A little while back, I stumbled across Margaret Bourke-White whilst looking up 20th Century female photographers, discovering her work among others such as Germaine Krull and Grete Stern. It goes without saying that each of these women were respectively brilliant at working behind the lens, and each are deserving of a writeup, but I was especially drawn to Bourke-White’s photographs of Marina Semyonova (fig. 1).

Taken at the Bolshoi Theatre in Moscow, this photo shows Semyonova – the first Soviet-trained prima ballerina – preparing herself ahead of a ballet performance. Semyonova’s body is folded into itself, revealing the physical contortions and movement required of her in order to reach and tie her ballet shoes. Her posture is considered, and the chair acts as a prop to help elongate her body and better display her ballet shoe all the while creating a tension between her body and the billowing tutu which surrounds her and presses upon the back of the chair. Semyonova is artfully staged, and her pose emulates the exaggerated stillness of the photographic form, reinforcing the expectation for ballerinas to always appear elegant, not just during a performance. Her left leg is deliberately aligned in a nod to her profession, recreating one half of the en pointe position and her outstretched arms provide an extension of the en pointe motif. This creates a clear shot for which Bourke-White could effectively capture Semyonova, allowing Bourke-White to play with light to illuminate Semyonova’s body and project a shadow onto the far wall.

With that said, what I found most appealing about this photo, is despite this photo having an editorial-like feel, the loose threads on Semyonova’s ballet shoes offer a reminder of the countless hours of practice required to become a ballerina, displaying the real-life implications of such a profession. This suggest that whilst Semyonova displays poise and elegance, these attributes have been mastered over time. However, the loose threads could also be linked to the USSR in relation to its second five-year plan which sought to prioritise agricultural and self-sufficiency ahead of consumer goods and frivolity, and the loose threads thereby reveal the unravelling of previous political and cultural practices.

Through considering such a beautiful photo, I wanted to discover more about Bourke-White’s work, particularly as this photo was taken during the political unease of the Soviet Union. My research revealed that Bourke-White excelled as a photographer and whose accomplishments were plentiful. Born in 1904, Margaret Bourke-White would go on to set up her own photography studio in 1928 in Ohio, but her work would soon take her abroad, namely to the likes of Russia, South Korea, India and Pakistan where she was commissioned to document moments of political divide, wars and social unrest.

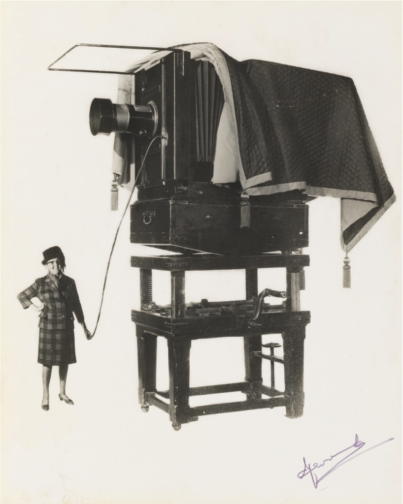

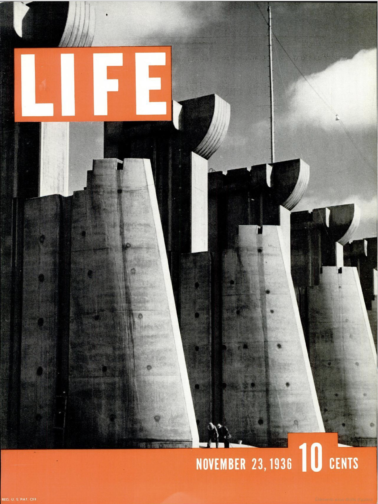

To name but a few of her impressive feats, Bourke-White was the first US photographer to enter the Soviet Union, the first US accredited female war photographer during WWII and responsible for the first cover for LIFE Magazine (fig. 2).

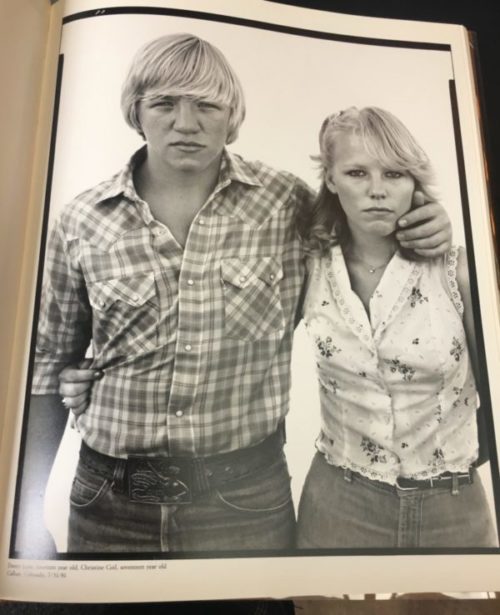

This cover highlights Bourke-White’s unique ability to take an imposing architectural structure and create a striking and an arresting image. She was commissioned to photograph this multi-million-dollar project of the Columbia River Basin and the construction of its impressive dam. The angle at which Bourke-White captured this photo and its emphasis on the symmetry of each of the concrete structures makes them appear – at least in my mind – as gigantic chess pieces bearing a similarity in shape to the ‘Rook’, with the two individuals symbolically positioned as pawns within this almighty chess board. The vibrant orange of the cover contrasts with the black and white image, at once cropping and framing the two individuals stood at the foot of the structure. The shot appears to reinforce the idea that these structures are in fact man made, with the two individuals attesting to the labour required to build such structures, and yet conveys the structures as colossal, unnatural, and otherworldly. Indeed, the editors notes that in commissioning Bourke-White they unexpectedly received, ‘a human document of American frontier life which, to them at least, was a revelation.’ This very observation highlights the talents of Bourke-White, and her ability to capture life within an otherwise intimidating concrete structure. This style of photography also calls to mind El Lissitzy and his photomontages for the SSSR na stroike (trans: USSR in construction) in 1932, with the overall global emphasis on self-sufficiency, driven by its workforce, who become the centre of El Lissitzy’s photomontage (fig. 3). This theme is echoed in Bourke-White’s photography, and the two share similar aims in trying to establish the strength of their respective cities and nations. To this effect, Bourke-White’s photography could be considered an artistic response to Constructivist periodical layouts and El Lissitzy’s earlier work.

The final photograph I would like to discuss is a self-portrait, rumoured to be Bourke-White’s favourite self-portrait, made with the U.S. 8th Air Force in 1943 (fig. 4).

In a similar vein to Bourke-White’s cover for LIFE Magazine, this photo marries machinery and industrial elements with humanity. While the airplane’s jets have been switched off, this photo conveys the necessity to be on constant standby, responding to any changes quickly and efficiently. Bourke-White has a tight hold of the large camera, figuratively and literally held down by the camera, and carries her flying helmet and goggles in her other hand with comparative ease. To this effect, this photo is suggestive of the precarity of the war and the need to be on constant alert as well as Bourke-White’s role to document the events. This is further reinforced by the inclusion of the plane in the frame – its proximity reinforces the fact that it is only a matter of time before this unit needs to reembark the plane.

At the same time, Bourke-White’s stance is relaxed yet upright, smiling as the wind blows through her hair. The tongues of her shoes are flopped over, giving the impression of a rare moment of respite, reinforced by the fact that their surroundings appear bare and uninhabited, suggesting a minimised threat or danger. The aviator jacket is fit with shearling trimmings, and complete with matching trousers, also lined with shearling, featuring leg-long zips and stained with a white powder residue. The crease patterns, particularly on the trousers, suggest the cramped conditions of the plane and it would appear as though Bourke-White has barely stepped off the plane. While her stance is relaxed, and she is surrounded by an expansive empty landscape, the trousers act as her ‘second skin’ and become a reminder that she did not have the luxury of space a few moments ago, and the trousers have not yet and will not likely get the chance to mould to their new surroundings, complete with the luxury of space, or Bourke-White’s standing pose.

Sadly, Margaret Bourke-White contracted Parkinson’s disease in 1953 and completed her last assignment for LIFE in 1957. With that said, she displayed great determination in trying to overcome the symptoms of her Parkinson’s, undergoing risky surgeries, and in true documentary photographer style, publicised and documented her fight against the disease, cementing her status as a formidable character and individual (fig. 5). She sadly passed away in 1971 but while her career was cut short by Parkinson’s, Bourke-White was rightly recognised in her lifetime as a true pioneer in documentary photography, particularly as a female photographer for her ability to uniquely capture people and places in and amongst periods of great change, showcasing their struggles and strengths.

By Georgina Johnston-Watt

Sources:

https://www.life.com/history/great-lady-with-a-camera-margaret-bourke-white-american-original/

https://www.life.com/lifestyle/parkinsons-disease-life-magazine/