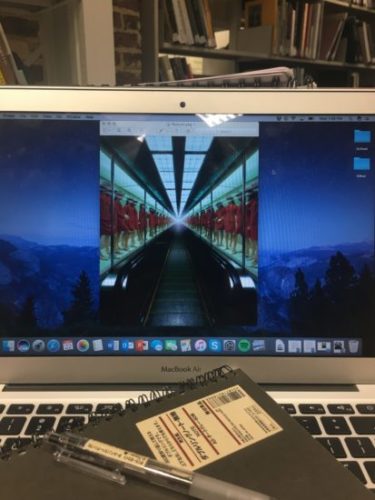

Miwa Yanagi’s 1990s photography series, Elevator Girl, presents a fascinating look at how fashion and photography can come together for a cultural critique. Yanagi studied textile design at the Kyoto City University of Arts, and incorporated this knowledge with a newfound interest in photography and performance art into one project. Beginning in the early 20th century, Japanese department stores hired beautiful, young women to operate the elevators in their buildings. She was made to dress up in the same outfit every day, and sit in a box repeating the same motions over and over again. The elevator girl was clearly a sexual object that represented the traditional patriarchal oppression of women in society, yet she was also a modern woman of the world that had a paying job and dressed in a contemporary, sophisticated manner. Yanagi’s photographs explore the traditional pressure and oppression that women still face in modern society. Take Elevator Girl House 1F, which shows rows of uniformed elevator girls displayed in a glass case.

They are dressed in identical red uniforms consisting of a skirt and double-breasted jacket, complete with a matching red hat and white pumps. They are each posed in a stiff, mannequin-like fashion within the glass display cases. The photograph invites the viewer onto the moving walkway to observe the models as if they are commodities to be bought and sold. Uniforms are powerful tools, in that they invite an immediate response of recognition. When you see someone in an army uniform, you automatically assume they must be a soldier of some kind. The red uniforms in Yanagi’s photograph give the viewer that sense of recognition to the elevator girls, but puts them in a different context. There is a simultaneous familiarity and alienation – the girls are recognizable in their uniforms and remain in a display context; however, they are now overtly the commodities in an endless row. There is also a sense of alienation in their similarity. The reflections of the lights above on the glass cases obscures their facial features. This coupled with their identical outfits makes them almost indistinguishable from one another.

Miwa Yanagi’s work in the Elevator Girl series investigates Japanese popular culture and consumer culture by appropriating their themes and satirizing them. Her series takes the patriarchal image of the elevator girl and uses it to shed light on the pressure and inequality Japanese women face. The photographs themselves resemble glossy fashion advertisements, thus criticizing both the way in which women are thought of as commodities and the consumer culture that gripped Japan as well. The ritualized performance of the elevator girl, the repetitive motions she makes everyday, the identical outfit she wore to other women, and the pressure put on her to appear alluring and youthful, is representative of the standardized roles women of any profession or status are expected to play. Her photographs increase the viewer’s feeling that there is something problematic about the elevator girls through a heightened sense of unreality that she achieves by placing the girls in eerily familiar, yet surreal settings. While her photographs in the Elevator Girl series are glossy, beautiful, and eye catching, they leave the viewer feeling unsettled, which is precisely their job.

By Olivia Chuba