Having recently completed an essay on the zenith of haute couture in the late 1940s, I was particularly keen to see the couture collections that just showed in Paris to determine whether or not the designs are as avant-garde and innovative as they were once considered to be.

I was not disappointed.

From the moment I saw Iris Van Herpen’s opening piece, a blue-purple gown floating down the runway as though the model were a giant weightless bird gliding just above the floor, I knew that there would be more to this collection than what meets the eye. In true couture fashion, the show, with its multitude of colors and voluminous, graceful shapes invites us to enter a dream world for eight minutes. Sculpture, architecture and painting are all brought together in the materiality of these 18 made-to-measure pieces, which seem to be (surprise!) actually wearable.

The collection, called ‘Shift Souls’, was presented in Paris at the Musée des Beaux-Arts. A series of billowing gowns contrasted more statuesque pieces. As Van Herpen states on her website, she was inspired by celestial cartography and mythology. She also wanted to consider ideals of the female body and how these have shifted through time: ‘the fluidity within identity change in Japanese mythology gave me the inspiration to explore the deeper meaning of identity and how immaterial and mutable it can become within current coalescence of our digital bodies.’

The digital component of the inspiration comes from advances in technology that have been made with regards to human and animal hybrids, called ‘Cybrids’. Van Herpen sees this research on ‘Cybrids’ as particularly intriguing, considering how it links to a long history of mythological stories about humans morphing into animals. She explains that her intention was not to take an ideological standpoint on these scientific developments; rather, the collection is an acknowledgment of the fact that new links are being made between biology and technology, expressing ‘the fact that this reality is upon us.’

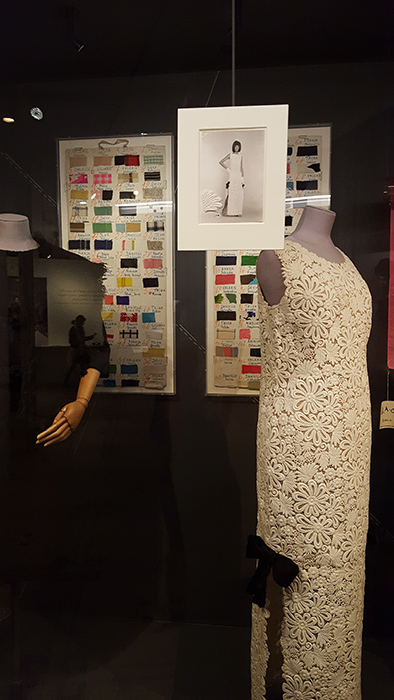

Right: Look 4/18, Iris Van Herpen couture Spring 2019, Credit: Vogue Runway

Technology was not just evoked, but it was actually used in the creation process of this futuristic collection. For instance, 3D laser cutting technology was employed to create the wave-like shape of some of the dresses. A few of the models also donned 3D-printed facial ornamentation, made from 3D scans of their faces. The technology was used to create lattice-like facemasks delineated from changes in the density of their facial structures.

Van Herpen also collaborated with former NASA engineer Kim Keever, who is now an artist bridging painting and photography in his work on waterscapes. Together, they designed the translucent dresses that resemble aqueous gas or clouds to evoke the idea of shifting, transient identities.

Movement was also explored throughout the collection. The primary fabrics used, silk and organza, made the dresses appear to float through space. Loose pieces of material on some of the dresses, like the ‘Galactic Glitch’ dress, fluttered slightly, creating an optical illusion like a flicker as the model walked. Other dresses had petal-shaped cutouts that projected outwards, resembling undulating waves, which gave the impression of water ripples emerging from the model’s body. This play on movement gives the pieces a sense of liminality; shifting, they create a blur, and we cannot tell where the dress actually existing in space.

Right: Look 5/18, Iris Van Herpen couture Spring 2019, Credit: Vogue Runway

Researching the historical development of haute couture since its conception at the end of the 19th century illuminates the fact that craftsmanship and savoir-faire are at the root of couture’s aura and prestige. I would argue that by forging an unlikely link between haute couture and technology, Van Herpen does not disavow the tradition of raw craftsmanship in couture, but rather, asks us to reconsider our preconceived notions of craftsmanship to create a new 21st century definition.

References: https://www.irisvanherpen.com/haute-couture